Revised at BL Nov 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literatura Orientu W Piśmiennictwie Polskim XIX W

Recenzent dr hab. Kinga Paraskiewicz Projekt okładki Igor Stanisławski Na okładce wykorzystano fragment anonimowego obrazu w stylu kad żarskim „Kobieta trzymaj ąca diadem” (Iran, poł. XIX w.), ze zbiorów Państwowego Muzeum Ermita żu, nr kat. VP 1112 Ksi ąż ka finansowana w ramach programu Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wy ższego pod nazw ą „Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” w latach 2013-2017 © Copyright by individual authors, 2016 ISBN 978-83-7638-926-4 KSI ĘGARNIA AKADEMICKA ul. św. Anny 6, 31-008 Kraków tel./faks 12-431-27-43, 12-421-13-87 e-mail: [email protected] Ksi ęgarnia internetowa www.akademicka.pl Spis tre ści Słowo wst ępne . 7 Ignacy Krasicki, O rymotwórstwie i rymotwórcach. Cz ęść dziewi ąta: o rymotwórcach wschodnich (fragmenty) . 9 § I. 11 § III. Pilpaj . 14 § IV. Ferduzy . 17 Assedy . 18 Saady . 20 Suzeni . 22 Katebi . 24 Hafiz . 26 § V. O rymotwórstwie chi ńskim . 27 Tou-fu . 30 Lipe . 31 Chaoyung . 32 Kien-Long . 34 Diwani Chod ża Hafyz Szirazi, zbiór poezji Chod ży Hafyza z Szyrazu, sławnego rymotwórcy perskiego przez Józefa S ękowskiego . 37 Wilhelm Münnich, O poezji perskiej . 63 Gazele perskiego poety Hafiza (wolny przekład z perskiego) przeło żył Jan Wiernikowski . 101 Józef Szujski, Rys dziejów pi śmiennictwa świata niechrze ścija ńskiego (fragmenty) . 115 Odczyt pierwszy: Świat ras niekaukaskich z Chinami na czele . 119 Odczyt drugi: Aryjczycy. Świat Hindusów. Wedy. Ksi ęgi Manu. Budaizm . 155 Odczyt trzeci: Epopeja indyjskie: Mahabharata i Ramajana . 183 Odczyt czwarty: Kalidasa i Dszajadewa [D źajadewa] . 211 Odczyt pi ąty: Aryjczycy. Lud Zendów – Zendawesta. Firduzi. Saadi. Hafis . 233 Piotr Chmielowski, Edward Grabowski, Obraz literatury powszechnej w streszczeniach i przekładach (fragmenty) . -

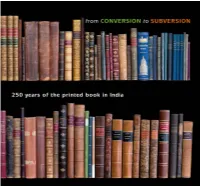

From Conversion to Subversion a Selection.Pdf

2014 FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India 2014 From Conversion to Subversion: 250 years of the printed book in India. A catalogue by Graham Shaw and John Randall ©Graham Shaw and John Randall Produced and published in 2014 by John Randall (Books of Asia) G26, Atlas Business Park, Rye, East Sussex TN31 7TE, UK. Email: [email protected] All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission in writing of the publisher and copyright holder. Designed by [email protected], Devon Printed and bound by Healeys Print Group, Suffolk FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India his catalogue features 125 works spanning While printing in southern India in the 18th the history of print in India and exemplify- century was almost exclusively Christian and Ting the vast range of published material produced evangelical, the first book to be printed in over 250 years. northern India was Halhed’s A Grammar of the The western technology of printing with Bengal Language (3), a product of the East India movable metal types was introduced into India Company’s Press at Hooghly in 1778. Thus by the Portuguese as early as 1556 and used inter- began a fertile period for publishing, fostered mittently until the late 17th century. The initial by Governor-General Warren Hastings and led output was meagre, the subject matter over- by Sir William Jones and his generation of great whelmingly religious, and distribution confined orientalists, who produced a number of superb to Portuguese enclaves. -

The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character

The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character from 1778 to 1978 by Fiona Georgina Elisabeth Ross School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1988 ProQuest Number: 10731406 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10731406 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 20618054 2 The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character from 1778 to 1978 Abstract The thesis traces the evolution of the printed image of the Bengali script from its inception in movable metal type to its current status in digital photocomposition. It is concerned with identifying the factors that influenced the shaping of the Bengali character by examining the most significant Bengali type designs in their historical context, and by analyzing the composing techniques employed during the past two centuries for printing the script. Introduction: The thesis is divided into three parts according to the different methods of type manufacture and composition: 1. The Development of Movable Metal Types for the Bengali Script Particular emphasis is placed on the early founts which lay the foundations of Bengali typography. -

Englishes Today / September 2015 / Volume II, Issue I ISBN : 2395 - 4809

Englishes Today / September 2015 / Volume II, Issue I ISBN : 2395 - 4809 ENGLISHES TODAY I September 2015 I Vol. I, Issue II I ISSN : 2395 4809 EXECUTIVE BOARD OF EDITORS Dr. Mitul Trivedi Prof. Piyush Joshi President H M Patel Institute of English Training and Research, Gujarat, The Global Association of English Studies INDIA. Dr. Paula Greathouse Prof. Shefali Bakshi Prof. Karen Andresa Dr M Saravanapava Iyer Tennessee Technological Amity University, Lucknow Santorum University of Jaffna Univesity, Tennessee, UNITED Campus, University de Santa Cruz do Sul Jaffna, SRI LANKA STATES OF AMERICA Uttar Pradesh, INDIA Rio Grande do Sul, BRAZIL Dr. Rajendrasinh Jadeja Prof. Sulabha Natraj Dr. Julie Ciancio Former Director, Prof. Ivana Grabar Professor and Head, Waymade California State University, H M Patel Institute of English University North, College of Education, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Training and Research Varaždin, CROATIA Gujarat, INDIA Gujarat, INDIA Dr. Momtazur Rahman Dr. Bahram Moghaddas Prof. Amrendra K. Sharma International University of Dr. Ipshita Hajra Sasmal Khazar Institute of Higher Dhofar University Business Agriculture and University of Hyderabad Education, Salalah, Technology, Dhaka, Hyderabad, INDIA. Mazandaran, IRAN. SULTANATE OF OMAN BANGLADESH Prof. Ashok Sachdeva Prof. Buroshiva Dasgupta Prof. Syed Md Golam Faruk Devi Ahilya University West Bengal University of Technology, West King Khalid University Indore, INDIA Bengal, INDIA Assir, SAUDI ARABIA Englishes Today / September 2015 / Volume II, Issue I ISBN : 2395 - 4809 ENGLISHES TODAY I September 2015 I Vol. I, Issue II I ISSN : 2395 4809 ontents... C 01 Training as a Scaffolding Tool for Esl Professional Development Dr. N V Bose A Study of Unique Collocations in Indian English : An Outcome of Language Contact 02 Phenomenon Ritika Srivastava 03 Situate Words/sentences in Various Contexts to enhance reading & writing Amita Patel A Teacher’s Tale of Challenges and Difficulties Faced in Primary Level E.L.T. -

Ancient, Medieval & Modern Indian History

ANCIENT, MEDIEVAL & MODERN INDIAN HISTORY ANCIENT INDIA arrived. Such a culture is called Chalcolithic which means the stone-copper phase. PRE-HISTORY The Chalcolithic people used different types Recent reported artefacts from Bori in of pottery of which black and red pottery was Maharashtra suggest the appearance of most popular. It was wheel made and human beings in India around 1.4 million painted with white line design. years ago. They venerated the mother goddess and Their first appearance to around 3000 BC, worshiped the bull. humans used only stone tools for different purposes. This period is, therefore known as INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION the Stone Age. The Indus Valley Civilization was an ancient Has been divided into Paleolithic age, civilization thriving along the Indus River Mesolithic age and Neolithic age. and the Ghaggar-Hakra River in what is now Pakistan and north-western India. THE PALEOLITHIC AGE (Old Stone) Among other names for this civilization is (500,00 BC – 8000 BC) the Harappan Civilization, in reference to its In India it developed in the Pleistocene first excavated city of Harappa. period or the Ice Age. An alternative term for the culture is The people of this age were food gathering Saraswati-Sindhu Civilization, based on the people who lived on hunting and gathering fact that most of the Indus Valley sites have wild fruits and vegetables. been found at the Halkra-Ghaggar River. They mainly used hand axes, cleavers, R.B. Dayaram Sahni first discovered choppers, blades, scrapers and burin. Their Harappa (on Ravi) in 1921. R.D. Banerjee tools were made of hard rock called discovered Mohenjodaro or Mound of the „quartzite‟, hence Paleolithic men are also Dead‟ (on Indus) in 1922. -

Paper 7 INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY

DDCE/SLM/M.A. Hist-Paper-VII Paper-VII INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY By Dr. Binod Bihari Satpathy 0 CONTENT INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY Unit.No. Chapter Name Page No Unit-I. Ancient Indian Historiography 1. Historical Sense in Ancient India, Idea of Bharatvarsha in Indian Tradition 2. Itihasa-Purana Tradition in Ancient India; Traditional History from the Vedas, Epics and Puranas 3. Jain Historiography and Buddhist Historiography Unit-II Medieval Indian Historiography 1. Historical Biography of Banabhatta and the Kashmir Chronicle of Kalhana 2. Arrival of Islam and its influence on Historical Tradition of India; Historiography of the Sultanate period – Alberuni’s –Kitab-ul-Hind and Amir Khusrau 3. Historiography of the Mughal Period – Baburnama, Abul Fazl and Badauni Unit-III. Orientalist, Imperial and colonial ideology and historian 1. William Jones and Orientalist writings on India 2. Colonial/ Imperialist Approach to Indian History and Historiography: James Mill, Elphinstone, and Vincent Smith 3. Nationalist Approach and writings to Indian History: R.G.Bhandarkar, H.C Raychoudhiri, and J.N.Sarkar Unit-IV. Marxist and Subaltern Approach to Indian History 1. Marxist approach to Indian History: D.D.Kosambi, R.S.Sharma, Romilla Thaper and Irfan Habib 2. Marxist writings on Modern India: Major assumptions 3. Subaltern Approach to Indian History- Ranjit Guha 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is pleasure to be able to complete this compilation work. containing various aspects of Indian historical writing tradition through ages. This material is prepared with an objective to familiarize the students of M.A History, DDCE Utkal University on the various aspcets of Indian historiography. This work would not have been possible without the support of the Directorate of Distance and Continuing Education, Utkal University. -

The Mahæbhærata in the West

The Mahæbhærata in the East and in the West From A. Holtzmann Vol. IV - 1895 Second Part The Mahæbhærata in the West Translated from German by Gilles Schaufelberger Chapter17 Aperçu sur la littérature English, German, French and American scholars have looked in the different parts of the epic, and in its relation with the rest of the Indian literature; but it is only since 1883 we have at our disposal a work dedicated to the Mahæbhærata, written by a Danish scholar, Sören Sörensen. 1. England has opened up the road into the Sanskrit literature’s studies, and particularly into Mahæbhærata’s. It is a young merchant, Charles Wilkins, who first gave a translation of the Bhagavadg∞tæ in 1785, opening thus the literature on the Mahæbhærata. A translation of the episode of Amƒtamanthana, from the Ædiparvan, followed. An other episode from the same, ›akuntalæ; followed in 1794 and 1795. In the annals of Oriental-literature, London, came out in 1820 and 1821 an anonymous translation of the beginning of the Ædiparvan, ending however with the Paulomæparvan, and not including the table of contents; this translation was also ascribed to Charles Wilkins, as in Gildemeister, bibl. Sanscr., p. 133: “interpres fuit Ch. Wilkins”; but H.H. Wilson in his Essays, ed. R. Reinhold Rost, T. I, p. 289, says more cautiously: “rendered into English, it is believed, by Sir Charles Wilkins”. In any case, from the introduction (dated Benares, 4th October 1784, the postscript 3rd December 1784) of the Governor General of India, the famous Warren Hastings, we know that Wilkins was working on a translation of the Mahæbhærata, “of which he has at this time translated more than a third”. -

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of RESEARCH INSTINCT Special

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH INSTINCT SRIMAD ANDAVAN ARTS & SCIENCE COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) IN COLLABORATION WITH COMPARATIVE LITERATURE ASSOCIATION OF INDIA Special Issue: April 2015 Report of the Conference The International Conference on New Perspectives on Comparative Literature and Translation Studies in collaboration with Comparative Literature Association of India was inaugurated by Dr. Dorothy Fegueira, Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature, University of Georgia, Athens, USA, on 07.03.2015 in Srimad Andavan Arts & Science College, Tiruchirappalli 05. Dr. J. Radhika, the Principal of the college welcomed the gathering. The meeting was presided over by Mr. N.Kasturirangan, the secretary of the college who was also the patron of the conference. Dr. S. Ramamurthy, Dean of Academics and Director of the conference introduced the theme of the conference and said that the conference seeks to take stock of the pedagogical developments in Comparative Literature all over the world in order to map the Indian context in terms of the same. He added that the conference proposes to discuss the state of Comparative Literature today and will explore how the discipline has responded to the pressures of a globalised educational matrix. Dr. Dorothy Fegueira in her keynote address referred to some theoretical and ethical concerns in the study of Comparative Literature and inaugurated the conference. Dr. Chandra Mohan, General Secretary, Comparative Literature Association of India & Former Vice-President International Comparative Literature Association, presided over the plenary session of the first day and traced the activities of Comparative Literature Association of India. Prof. Seighild Bogumil, Eminent Professor in French and German Comparative Literature from Ruhr University at Bochum delivered her special address on the Comparative Literature Scenarios in Europe with reference to France and Germany. -

Arabian and Persian Language and Literature: Items 67–98 Section 3 Important Books from the Western World: Items 99–126

Peter Harrington london We are exhibiting at these fairs 24–26 May london The ABA Rare Book Fair Battersea Evolution Queenstown Road, London SW11 www.rarebookfairlondon.com 28 June – 4 July masterpiece The Royal Hospital Chelsea London SW3 www.masterpiecefair.com 6–8 July melbourne Melbourne Rare Book Fair Wilson Hall, The University of Melbourne www.rarebookfair.com VAT no. gb 701 5578 50 Peter Harrington Limited. Registered office: WSM Services Limited, Connect House, 133–137 Alexandra Road, Wimbledon, London SW19 7JY. Registered in England and Wales No: 3609982 Front cover illustration from item 1 in the catalogue. Design: Nigel Bents; Photography: Ruth Segarra. Peter Harrington london Books to be exhibited at the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair 2018 Section 1 The Arab and Islamic World: items 1–66 Section 2 Arabian and Persian language and literature: items 67–98 Section 3 Important Books from the Western World: items 99–126 mayfair chelsea Peter Harrington Peter Harrington 43 Dover Street 100 Fulham Road London w1s 4ff London sw3 6hs uk 020 3763 3220 uk 020 7591 0220 eu 00 44 20 3763 3220 eu 00 44 20 7591 0220 usa 011 44 20 3763 3220 usa 011 44 20 7591 0220 www.peterharrington.co.uk 1 a wealthy and high-ranking patron as a token of authority The Arab and Islamic World instead of an item for everyday use. provenance: formerly in the collection of Captain R. G. 1 Southey (d. 1976). AL-JAZULI (Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn £7,500 [124658] Sulayman ibn Abu Bakr al-Jazuli al-Simlali). Dala’il al-Khayrat (Guides to Goodness), with two Highly detailed and copiously illustrated survey of the illuminated depictions of the holy cities of Mecca and Bakuvian oil industry Medina. -

Catalogue 182: Orientalia

ORIENTALISM JEFF WEBER RARE BOOKS Catalogue 182 Catalogue 182: OREINTALISM SPRING 2016 IT IS WITH GREAT PRIDE that I issue this catalogue devoted to my wife. From the first time that I met her I became interested in the history, literature and culture of ancient Persia, or modern day Iran. My college degree from UCLA focused on this field, studying under Dr. Amin Banani. My first serious book collection was on Persian literature in translation. My grandfather even wrote a bibliography on the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Thus applying my bibliographic zeal to the history of Persia, including language, travel, art, and the interaction between the east and west results in this offering. Persian culture is rich with history and lessons, art, design, story-telling and tradition. I know that those who know Iranians know they are a proud and remarkable people who bring much to this world and whose history is often much deeper than one imagines. PLEASE MAKE NOTE OF OUR NEW ADDRESS AS WE HAVE RECENTLY MOVED. On-line are more than 10,000 antiquarian books in the fields of science, medicine, Americana, classics, books on books and fore-edge paintings. The books in current catalogues are not listed on-line until mail-order clients have priority. Our inventory is available for viewing by appointment. Terms are as usual. Shipping extra. RECENT CATALOGUES: 176: Revolutions in Science (469 items) 177: Sword & Pen (202 items) 178: Wings of Imagination (416 items) 179: Jeff’s Fables (127 items) 180: The Physician’s Pulse-Watch (138 items) 181: Bookseller’s Cabinet (87 items) COVER: 33 PARDOE Jeff Weber & Mahshid Essalat-Weber J E F F W E B E R R A R E B O O K S 1815 Oak Ave Carlsbad, California 92008-1103 TELEPHONES: cell: 323 333-4140 e-mail: [email protected] www.WEBERRAREBOOKS.COM Featuring Marvelous Imagery from the Middle East Culture & Northern Africa 1 [Algiers, Algeria; photograph albums] Two photograph albums, ca. -

Construction of an Indian Literary Historiography Through HH Wilson's

International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science (IJELS) Vol-4, Issue-5, Sep – Oct 2019 https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.45.13 ISSN: 2456-7620 Construction of an Indian Literary Historiography through H.H. Wilson’s “Hindu Fiction” Astha Saklani Department of English, University of Delhi, Delhi, India Abstract— Postcolonial scholars are largely in consensus that the modern Indian literary historiography is a gift of our colonial legacy. Most of these scholars have looked at the classical Sanskrit texts and their treatment by the Orientalists. One genre that is often ignored, however, by them, is that of fables. Fables formed a significant section of the Indian literature that was studied by the orientalists. The colonial intellectuals’s interest in selected Indian fables is reflected in H.H. Wilson’s essay entitled “Hindu Fiction”. The essay not only helps in deconstruting the motive behind British pre-occupation in the genre but also is significant in deconstructing the colonial prejudices which plagued the minds of the nineteenth century European scholars in general and colonial scholars in particular regarding the Asian and African communities and their literature. Keywords— Colonial literary histography, Indian fables, Panchatantra, Post-colonialism, Hindu fiction. Postcolonial scholars, beginning with Edward Said, have literature and was widely analysed and institutionalised. exposed the project undertaken by the Orientalist scholars This paper is a study of a crucial essay on Indian fables; to study the history, culture and literature of the colonies H.H. Wilson’s essay entitled “Hindu Fiction”, which in order to further their imperialist ambitions. Bernard discusses the genre of apologues, its origin in India and its Cohn, Aamir Mufti and Rama Sundari Mantena focused circulation all across the world.2 The paper delves deep on the construction of Indian nationalism by the late into the text in order to examine the treatment given to the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century genre by the scholars during colonialism. -

Persian Romanization Bahá'ís Use a System Standardized by Shoghi Effendi, Which He Initiated in a General Letter on March 12, 1923

Persian Letters of the Alphabet Initial Medial Final Alone Romanization (omit (see Note 1 ا ﺎ ﺎ ا b ﺏ ﺐ ﺒ ﺑ p ﭖ ﭗ ﭙ ﭘ t ﺕ ﺖ ﺘ ﺗ s ﺙ ﺚ ﺜ ﺛ j ﺝ ﺞ ﺠ ﺟ ch ﭺ ﭻ ﭽ ﭼ ḥ ﺡ ﺢ ﺤ ﺣ kh ﺥ ﺦ ﺨ ﺧ d ﺩ ﺪ ﺪ ﺩ z ﺫ ﺬ ﺬ ﺫ r ﺭ ﺮ ﺮ ﺭ z ﺯ ﺰ ﺰ ﺯ zh ﮊ ﮋ ﮋ ﮊ s ﺱ ﺲ ﺴ ﺳ sh ﺵ ﺶ ﺸ ﺷ ṣ ﺹ ﺺ ﺼ ﺻ z̤ ﺽ ﺾ ﻀ ﺿ ṭ ﻁ ﻂ ﻄ ﻃ ẓ ﻅ ﻆ ﻈ ﻇ (ayn) ‘ ﻉ ﻊ ﻌ ﻋ gh ﻍ ﻎ ﻐ ﻏ f ﻑ ﻒ ﻔ ﻓ q ﻕ ﻖ ﻘ ﻗ (k (see Note 2 ﻙ ﻚ ﻜ ﻛ (g (see Note 3 ﮒ ﮓ ﮕ ﮔ l ﻝ ﻞ ﻠ ﻟ m ﻡ ﻢ ﻤ ﻣ n ﻥ ﻦ ﻨ ﻧ (v (see Note 3 ﻭ ﻮ ﻮ ﻭ (h (see Note 4 ة ، ه ـﺔ ، ﻪ ﻬ ﻫ (y (see Note 3 ﻯ ﻰ ﻴ ﻳ Vowels and Diphthongs (see Note 5) ī ◌ِ ﻯ (ā (see Note 6 ا◌َ ، آ a ◌َ aw ْ◌َ ﻭ (á (see Note 7 ◌َ ﻯ u ◌ُ ay ◌َ ﻯْ ū ◌ُ ﻭ i ◌ِ Notes hamzah) and (maddah), see rule 1(a). For the) ء alif) to support) ا For the use of .1 alif) to) ا and , see rules 4 and 5 respectively. For the use of ء romanization of represent the long vowel romanized ā, see the table of vowels and diphthongs, and rule 1(b).