Introduction to Charles Wilkin's Bhagavad Gita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literatura Orientu W Piśmiennictwie Polskim XIX W

Recenzent dr hab. Kinga Paraskiewicz Projekt okładki Igor Stanisławski Na okładce wykorzystano fragment anonimowego obrazu w stylu kad żarskim „Kobieta trzymaj ąca diadem” (Iran, poł. XIX w.), ze zbiorów Państwowego Muzeum Ermita żu, nr kat. VP 1112 Ksi ąż ka finansowana w ramach programu Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wy ższego pod nazw ą „Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” w latach 2013-2017 © Copyright by individual authors, 2016 ISBN 978-83-7638-926-4 KSI ĘGARNIA AKADEMICKA ul. św. Anny 6, 31-008 Kraków tel./faks 12-431-27-43, 12-421-13-87 e-mail: [email protected] Ksi ęgarnia internetowa www.akademicka.pl Spis tre ści Słowo wst ępne . 7 Ignacy Krasicki, O rymotwórstwie i rymotwórcach. Cz ęść dziewi ąta: o rymotwórcach wschodnich (fragmenty) . 9 § I. 11 § III. Pilpaj . 14 § IV. Ferduzy . 17 Assedy . 18 Saady . 20 Suzeni . 22 Katebi . 24 Hafiz . 26 § V. O rymotwórstwie chi ńskim . 27 Tou-fu . 30 Lipe . 31 Chaoyung . 32 Kien-Long . 34 Diwani Chod ża Hafyz Szirazi, zbiór poezji Chod ży Hafyza z Szyrazu, sławnego rymotwórcy perskiego przez Józefa S ękowskiego . 37 Wilhelm Münnich, O poezji perskiej . 63 Gazele perskiego poety Hafiza (wolny przekład z perskiego) przeło żył Jan Wiernikowski . 101 Józef Szujski, Rys dziejów pi śmiennictwa świata niechrze ścija ńskiego (fragmenty) . 115 Odczyt pierwszy: Świat ras niekaukaskich z Chinami na czele . 119 Odczyt drugi: Aryjczycy. Świat Hindusów. Wedy. Ksi ęgi Manu. Budaizm . 155 Odczyt trzeci: Epopeja indyjskie: Mahabharata i Ramajana . 183 Odczyt czwarty: Kalidasa i Dszajadewa [D źajadewa] . 211 Odczyt pi ąty: Aryjczycy. Lud Zendów – Zendawesta. Firduzi. Saadi. Hafis . 233 Piotr Chmielowski, Edward Grabowski, Obraz literatury powszechnej w streszczeniach i przekładach (fragmenty) . -

1 Title: Enlightenment and Empire, Mughals and Marathas: The

Title: Enlightenment and Empire, Mughals and Marathas: The Religious History of Indian in the Work of East India Company Servant, Alexander Dow. Abstract: This article situates the work of East India Company servant Alexander Dow (1735-1779), principally his writings on the history and future state of India, in contemporary debates about empire, religion and enlightened government. To do so it offers a sustained analysis of his 1772 essay “A Dissertation Concerning the Origin and Nature of Despotism in Hindostan”, as well as his proposals for the restoration of Bengal, both of which played an influential part in shaping the preoccupations with Mughal history that dominated the contemporary crisis in the Company’s legitimacy. By linking these texts to his earlier work on ‘Hindoo’ religion, it will argue that Dow’s analysis of the relationship between certain religious cultures and their civic qualities was rooted in a deist perspective. It doing so it restores the enlightenment components of Dow’s thought, and their impact on the ideology of empire, in a crucial period of British expansion in India. Keywords: Empire, Enlightenment, India, Eighteenth Century, East India Company, Religion 1 Historians are increasingly concerned with the Enlightenment’s extra-European context.1 In particular, recognising that international commerce and exchange were its material context, scholars have turned their attention to Enlightenment attitudes to empire. For Sankar Muthu this has meant tracing anti-imperialist strands of enlightenment thought.2 This -

The Upanishads, Vol I

The Upanishads, Vol I Translated by F. Max Müller The Upanishads, Vol I Table of Contents The Upanishads, Vol I........................................................................................................................................1 Translated by F. Max Müller...................................................................................................................1 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................7 PROGRAM OF A TRANSLATION...............................................................................................................19 THE SACRED BOOKS OF THE EAST........................................................................................................20 TRANSLITERATION OF ORIENTAL ALPHABETS,..............................................................................25 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................26 POSITION OF THE UPANISHADS IN VEDIC LITERATURE.......................................................30 DIFFERENT CLASSES OF UPANISHADS.......................................................................................31 CRITICAL TREATMENT OF THE TEXT OF THE UPANISHADS................................................33 MEANING OF THE WORD UPANISHAD........................................................................................38 WORKS ON THE UPANISHADS....................................................................................................................41 -

Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets

Voices from the Margins: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets by Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2016 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2018 © Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes 2018 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, a thesis/dissertation entitled: Voices from the Margins: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets submitted by Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Asian Studies Examining Committee: Adheesh Sathaye, Asian Studies Supervisor Thomas Hunter, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member Anne Murphy, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member Additional Examiner ii Abstract In this thesis, I discuss classical Sanskrit women poets and propose an alternative reading of two specific women’s works as a way to complicate current readings of Classical Sanskrit women’s poetry. I begin by situating my work in current scholarship on Classical Sanskrit women poets which discusses women’s works collectively and sees women’s work as writing with alternative literary aesthetics. Through a close reading of two women poets (c. 400 CE-900 CE) who are often linked, I will show how these women were both writing for a courtly, educated audience and argue that they have different authorial voices. In my analysis, I pay close attention to subjectivity and style, employing the frameworks of Sanskrit aesthetic theory and Classical Sanskrit literary conventions in my close readings. -

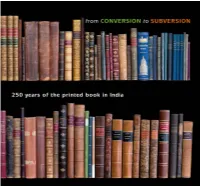

From Conversion to Subversion a Selection.Pdf

2014 FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India 2014 From Conversion to Subversion: 250 years of the printed book in India. A catalogue by Graham Shaw and John Randall ©Graham Shaw and John Randall Produced and published in 2014 by John Randall (Books of Asia) G26, Atlas Business Park, Rye, East Sussex TN31 7TE, UK. Email: [email protected] All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission in writing of the publisher and copyright holder. Designed by [email protected], Devon Printed and bound by Healeys Print Group, Suffolk FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India his catalogue features 125 works spanning While printing in southern India in the 18th the history of print in India and exemplify- century was almost exclusively Christian and Ting the vast range of published material produced evangelical, the first book to be printed in over 250 years. northern India was Halhed’s A Grammar of the The western technology of printing with Bengal Language (3), a product of the East India movable metal types was introduced into India Company’s Press at Hooghly in 1778. Thus by the Portuguese as early as 1556 and used inter- began a fertile period for publishing, fostered mittently until the late 17th century. The initial by Governor-General Warren Hastings and led output was meagre, the subject matter over- by Sir William Jones and his generation of great whelmingly religious, and distribution confined orientalists, who produced a number of superb to Portuguese enclaves. -

List of Books Available on Calibre Software

LIST OF BOOKS AVAILABLE ON CALIBRE SOFTWARE (PLEASE CONTACT LIBRARY STAFF TO ACCESS CALIBRE) 1. 1.doc · Kamal Swaroop 2. 50 Volume RGS Journal Table of Contents s · Unknown 3. 1836 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 4. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 : THE HISTORY, THE ANTIQUITIES, THE ARTS AND SCIENCES, AND LITERATURE ASIA . · Asiatic Society, Calcutta 5. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 6. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 7. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 8. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 9 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 9. 1856 JASB Index AR 19 to JASB 23 · Unknown 10. 1856 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 24 s+m · Unknown 11. 1862 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 30 s+m · Unknown 12. 1866 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 34 s+m · Unknown 13. 1867 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 35 s+m · Unknown 14. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 15. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 16. 1951-52.PMD · Unknown 17. 1952-53-(Final).PMD · Unknown 18. 1953-54.pmd · Unknown 19. 1954-55.pmd · Unknown 20. 1955-56.pmd · Unknown 21. 1956-57.pmd · Unknown 22. 1957-58(interim) 1957-58-1958-59 · Unknown 23. 62569973-Text-of-Justice-Soumitra-Sen-s-Defence · Unknown 24. ([Views of the East; Comprising] India, Canton, [And the Shores of the Red Sea · Robert Elliot 25. -

A Cymmrodor Claims Kin in Calcutta: an Assessment of Sir William Jones As Philologer, Polymath, and Pluralist

Chap 004_Kin in Calcutta 2/8/05 9:21 am Page 50 A Cymmrodor claims kin in Calcutta: an assessment of Sir William Jones as philologer, polymath, and pluralist by Garland Cannon and Michael J. Franklin* It was a custom among the Ancient Britons (and still retained in Anglesey) for the most knowing among them in the descent of families, to send their friends of the same stock or family, a dydd calan Ionawr a calennig, [New Year’s gift] a present of their pedigree; [...] [T]he very thought of those brave people, who struggled so long with a superior power for their liberty, inspires me with such an idea of them, that I almost adore their memories.1 This genealogical present, of inherent interest to all the ‘earliest natives’ [Cymmrodorion] of Wales and beyond, was sent in a letter of New Year’s Day 1748 by the ‘learned British antiquary’ and co-founder of this society, Lewis Morris (1701-65) to his friend William ap Sion Siors (son of John George), known in London as William Jones, FRS (c.1675-1749), ‘Longitude Jones’, celebrated mathematician, disseminator of Newtonian theory, and father of the future Orientalist.2 This document, now sadly lost, showed that the Morrises and the Joneses were closely related, sharing an ancestry deriving from Hwfa ap Cynddelw and the princes of Gwynedd. Exactly why a seemingly insignificant Ynys Môn parish should produce within two generations a scholar of the calibre of William Jones sen. and polymaths of such importance as Lewis Morris and Sir William Jones remains something of a mystery.3 This new study of Jones the linguist and literary * The authors would like to express their gratitude to Professor Hal W. -

The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character

The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character from 1778 to 1978 by Fiona Georgina Elisabeth Ross School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1988 ProQuest Number: 10731406 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10731406 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 20618054 2 The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character from 1778 to 1978 Abstract The thesis traces the evolution of the printed image of the Bengali script from its inception in movable metal type to its current status in digital photocomposition. It is concerned with identifying the factors that influenced the shaping of the Bengali character by examining the most significant Bengali type designs in their historical context, and by analyzing the composing techniques employed during the past two centuries for printing the script. Introduction: The thesis is divided into three parts according to the different methods of type manufacture and composition: 1. The Development of Movable Metal Types for the Bengali Script Particular emphasis is placed on the early founts which lay the foundations of Bengali typography. -

History of Early Sanskrit Scholars

HISTORY OF EARLY SANSKRIT SCHOLARS Scientific study of India/Hinduism and Sanskrit language started at the end of the eighteen-century. Sir William Jones who is called as father of Indology started Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784 with the help of his colleagues Charles Wilkins (1749-1836, Alexander Hamilton (1762-1824) and Colebrook ( ) These Scholars translated many Sanskrit texts into English which in tern got translated to other European languages which created tremendous interest in Sanskrit learning and Hinduism. Many European universities started Sanskrit chairs and study of Hinduism. 1. France was ahead of England. Alexander Hamilton started teaching Sanskrit at the Ecole des Langues Orientales Vivantes at Paris in 1803. At famous Paris University first Sanskrit Chair was established at college de France in 1814. During the same period Eugene Burnouf (1801-1852) delivered his famous lectures on Vedas. 2. In Germany Sanskrit Chair was established in 1816. In 1816 Franz Bopp forwarded the theory of common ancestry for Sanskrit, Greek and Latin. This study of his gave birth to a new branch in Philology called comparative philology. Many German scholars of repute emerged in 19 th century that no other country in Europe could match. 3. In England Sanskrit was first taught at the training college of East India Company at Hertford and the first chair of Sanskrit was started much latter at Oxford named after Boden. H.H.Wilson was the firs Boden professor. Later Chairs were created at London,Cambridge and Edinburgh. 4. In Holland Sanskrit learning started late in 1865 at state University of Leiden and great Sanskrit scholar Hendrik Kern was appointed as first professor of Sanskrit. -

E-Teaching Capsule for Srimad- Bhagavad-Gita by Preeti Patel

E-Teaching Capsule for Srimad- Bhagavad-Gita by Preeti Patel Submission date: 24-Oct-2018 12:04PM (UTC+0530) Submission ID: 1025838127 File name: Preeti_chapters_library.pdf (6.29M) Word count: 39661 Character count: 206277 E-Teaching Capsule for Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā A dissertation submitted to the University of Hyderabad for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sanskrit Studies by Patel Preeti Khimji 10HSPH01 Department of Sanskrit Studies School of Humanities University of Hyderabad Hyderabad 2018 E-Teaching Capsule for Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā A dissertation submitted to the University of Hyderabad for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sanskrit Studies by Patel Preeti Khimji 10HSPH01 under the guidance of Prof. Amba Kulkarni Professor, Department of Sanskrit Studies Department of Sanskrit Studies School of Humanities University of Hyderabad Hyderabad 2018 Declaration I, Patel Preeti Khimji, hereby declare that the work embodied in this dissertation en- titled “E-Teaching Capsule for Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā” is carried out by me under the supervision of Prof. Amba P. Kulkarni, Professor, Department of Sanskrit Studies, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad and has not been submitted for any degree in part or in full to this university or any other university. I hereby agree that my thesis can be deposited in Shodhganga/INFLIBNET. A report on plagiarism statistics from the University Librarian is enclosed. Patel Preeti Khimji 10HSPH01 Date: Place: Hyderabad Signature of the Supervisor Certificate This is to certify that the thesis entitled E-Teaching Capsule for Śrīmad-Bhagavad- Gītā Submitted by Patel Preeti Khimji bearing registration number 10HSPH01 in par- tial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Humanities is a bonafide work carried out by her under my supervision and guid- ance. -

Englishes Today / September 2015 / Volume II, Issue I ISBN : 2395 - 4809

Englishes Today / September 2015 / Volume II, Issue I ISBN : 2395 - 4809 ENGLISHES TODAY I September 2015 I Vol. I, Issue II I ISSN : 2395 4809 EXECUTIVE BOARD OF EDITORS Dr. Mitul Trivedi Prof. Piyush Joshi President H M Patel Institute of English Training and Research, Gujarat, The Global Association of English Studies INDIA. Dr. Paula Greathouse Prof. Shefali Bakshi Prof. Karen Andresa Dr M Saravanapava Iyer Tennessee Technological Amity University, Lucknow Santorum University of Jaffna Univesity, Tennessee, UNITED Campus, University de Santa Cruz do Sul Jaffna, SRI LANKA STATES OF AMERICA Uttar Pradesh, INDIA Rio Grande do Sul, BRAZIL Dr. Rajendrasinh Jadeja Prof. Sulabha Natraj Dr. Julie Ciancio Former Director, Prof. Ivana Grabar Professor and Head, Waymade California State University, H M Patel Institute of English University North, College of Education, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Training and Research Varaždin, CROATIA Gujarat, INDIA Gujarat, INDIA Dr. Momtazur Rahman Dr. Bahram Moghaddas Prof. Amrendra K. Sharma International University of Dr. Ipshita Hajra Sasmal Khazar Institute of Higher Dhofar University Business Agriculture and University of Hyderabad Education, Salalah, Technology, Dhaka, Hyderabad, INDIA. Mazandaran, IRAN. SULTANATE OF OMAN BANGLADESH Prof. Ashok Sachdeva Prof. Buroshiva Dasgupta Prof. Syed Md Golam Faruk Devi Ahilya University West Bengal University of Technology, West King Khalid University Indore, INDIA Bengal, INDIA Assir, SAUDI ARABIA Englishes Today / September 2015 / Volume II, Issue I ISBN : 2395 - 4809 ENGLISHES TODAY I September 2015 I Vol. I, Issue II I ISSN : 2395 4809 ontents... C 01 Training as a Scaffolding Tool for Esl Professional Development Dr. N V Bose A Study of Unique Collocations in Indian English : An Outcome of Language Contact 02 Phenomenon Ritika Srivastava 03 Situate Words/sentences in Various Contexts to enhance reading & writing Amita Patel A Teacher’s Tale of Challenges and Difficulties Faced in Primary Level E.L.T. -

The Death of Sanskrit*

The Death of Sanskrit* SHELDON POLLOCK University of Chicago “Toutes les civilisations sont mortelles” (Paul Valéry) In the age of Hindu identity politics (Hindutva) inaugurated in the 1990s by the ascendancy of the Indian People’s Party (Bharatiya Janata Party) and its ideo- logical auxiliary, the World Hindu Council (Vishwa Hindu Parishad), Indian cultural and religious nationalism has been promulgating ever more distorted images of India’s past. Few things are as central to this revisionism as Sanskrit, the dominant culture language of precolonial southern Asia outside the Per- sianate order. Hindutva propagandists have sought to show, for example, that Sanskrit was indigenous to India, and they purport to decipher Indus Valley seals to prove its presence two millennia before it actually came into existence. In a farcical repetition of Romantic myths of primevality, Sanskrit is consid- ered—according to the characteristic hyperbole of the VHP—the source and sole preserver of world culture. The state’s anxiety both about Sanskrit’s role in shaping the historical identity of the Hindu nation and about its contempo- rary vitality has manifested itself in substantial new funding for Sanskrit edu- cation, and in the declaration of 1999–2000 as the “Year of Sanskrit,” with plans for conversation camps, debate and essay competitions, drama festivals, and the like.1 This anxiety has a longer and rather melancholy history in independent In- dia, far antedating the rise of the BJP. Sanskrit was introduced into the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India (1949) as a recognized language of the new State of India, ensuring it all the benefits accorded the other fourteen (now seventeen) spoken languages listed.