The Mahæbhærata in the West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literatura Orientu W Piśmiennictwie Polskim XIX W

Recenzent dr hab. Kinga Paraskiewicz Projekt okładki Igor Stanisławski Na okładce wykorzystano fragment anonimowego obrazu w stylu kad żarskim „Kobieta trzymaj ąca diadem” (Iran, poł. XIX w.), ze zbiorów Państwowego Muzeum Ermita żu, nr kat. VP 1112 Ksi ąż ka finansowana w ramach programu Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wy ższego pod nazw ą „Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” w latach 2013-2017 © Copyright by individual authors, 2016 ISBN 978-83-7638-926-4 KSI ĘGARNIA AKADEMICKA ul. św. Anny 6, 31-008 Kraków tel./faks 12-431-27-43, 12-421-13-87 e-mail: [email protected] Ksi ęgarnia internetowa www.akademicka.pl Spis tre ści Słowo wst ępne . 7 Ignacy Krasicki, O rymotwórstwie i rymotwórcach. Cz ęść dziewi ąta: o rymotwórcach wschodnich (fragmenty) . 9 § I. 11 § III. Pilpaj . 14 § IV. Ferduzy . 17 Assedy . 18 Saady . 20 Suzeni . 22 Katebi . 24 Hafiz . 26 § V. O rymotwórstwie chi ńskim . 27 Tou-fu . 30 Lipe . 31 Chaoyung . 32 Kien-Long . 34 Diwani Chod ża Hafyz Szirazi, zbiór poezji Chod ży Hafyza z Szyrazu, sławnego rymotwórcy perskiego przez Józefa S ękowskiego . 37 Wilhelm Münnich, O poezji perskiej . 63 Gazele perskiego poety Hafiza (wolny przekład z perskiego) przeło żył Jan Wiernikowski . 101 Józef Szujski, Rys dziejów pi śmiennictwa świata niechrze ścija ńskiego (fragmenty) . 115 Odczyt pierwszy: Świat ras niekaukaskich z Chinami na czele . 119 Odczyt drugi: Aryjczycy. Świat Hindusów. Wedy. Ksi ęgi Manu. Budaizm . 155 Odczyt trzeci: Epopeja indyjskie: Mahabharata i Ramajana . 183 Odczyt czwarty: Kalidasa i Dszajadewa [D źajadewa] . 211 Odczyt pi ąty: Aryjczycy. Lud Zendów – Zendawesta. Firduzi. Saadi. Hafis . 233 Piotr Chmielowski, Edward Grabowski, Obraz literatury powszechnej w streszczeniach i przekładach (fragmenty) . -

Edward Elbridge Salisbury and the AOS Roberta L Dougherty, Yale University

Yale University From the SelectedWorks of Roberta L. Dougherty Spring March 17, 2017 AOS 2017: Edward Elbridge Salisbury and the AOS Roberta L Dougherty, Yale University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/bintalbalad/23/ [SLIDE] An American Orientalist: Edward Elbridge Salisbury and the AOS AOS members probably know the subject of my paper this afternoon as one of the society’s prominent officers during its first half-century, having served as its Corresponding Secretary (1846-1857), President (twice, in 1863-1866, and again from 1873-1880),1 and, at various times, as member of the Board of Directors, a Vice President, and for his service on the publications committee of the Journal. The members may be less familiar with the fact that his appointment at Yale College as professor of Arabic and Sanskrit language and literature in 1841 was the first such professorship in the Americas--and in fact the first university professorship of any kind in the Americas.2 They may also be unaware of the extent to which Salisbury supported the early establishment of the Society not only with his time, but his means. Part of the AOS lore regarding Salisbury is that he was present at the society’s founding in 1842, but this was not actually the case. Although his name was indeed on the list of members first elected to the society after its founding, he may have remained unaware of his election for over a year. He was with some effort persuaded to serve as its Corresponding Secretary, and with even more difficulty persuaded to become its President. -

Human Sacrifice, Karma and Asceticism in Jantu’S Tale of the Mahābhārata.”

A Final Response to Philipp A. Maas, “Negotiating Efficiencies: Human Sacrifice, Karma and Asceticism in Jantu’s Tale of the Mahābhārata.” Vishwa Adluri, Hunter College, New York Interpretation of the narrative and using intertextual connections as evidence I disagree that “the occurrence of the word ‘jantu’ in the KU and in Shankara[’]s commentary” does not “help to understand the MBh passage under discussion.” On the contrary, it is highly relevant. The term jantu’s resonances in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad permit us to understand the philosophical dimension of the narrative. It suggests that an important philosophical argument is being worked out in the narrative rather than the kind of jostling for political authority between Brahmanism and śramaṇa traditions you see in the text. Even if you are not interested in philosophical questions, it is disingenuous to suggest that “Shankara interpreted the Upanishads from the perspective of Advaita Vedanta many hundred years after these works were composed. His approach is not historical but philosophical, which is fully justified, but his testimony does not help to determine what the works he comments upon meant at the time and in the contexts of their composition.” Is it really credible that Śaṁkara, interpreting the Mahābhārata some centuries after it was composed, did not correctly understand the Mahābhārata, while you, writing two millennia later, do? Can you seriously claim that Śaṁkara is not aware of the history of the text (although you are), while being ignorant of the intertextual connections between this narrative and the Kaṭha Upaniṣad? Isn’t the real reason that you claim a long period of development that it is only on this premise that you can claim that Śaṁkara’s interpretation is not relevant, and that yours, on the contrary, has greater objectivity? The notion that only the contemporary scholar, applying the historical-critical method, has access to the true or the most original meaning of the text is deeply rooted in 1 modernity. -

John Benjamins Publishing Company Historiographia Linguistica 41:2/3 (2014), 375–379

Founders of Western Indology: August Wilhelm von Schlegel and Henry Thomas Colebrooke in correspondence 1820–1837. By Rosane Rocher & Ludo Rocher. (= Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, 84.) Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013, xv + 205 pp. ISBN 978-3-447-06878-9. €48 (PB). Reviewed by Leonid Kulikov (Universiteit Gent) The present volume contains more than fifty letters written by two great scholars active in the first decades of western Indology, the German philologist and linguist August Wilhelm von Schlegel (1767–1789) and the British Indologist Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1765–1837). It can be considered, in a sense, as a sequel (or, rather, as an epistolary appendix) to the monograph dedicated to H. T. Colebrooke that was published by the editors one year before (Rocher & Rocher 2012). The value of this epistolary heritage left by the two great scholars for the his- tory of humanities is made clear by the editors, who explain in their Introduction (p. 1): The ways in which these two men, dissimilar in personal circumstances and pro- fessions, temperament and education, as well as in focus and goals, consulted with one another illuminate the conditions and challenges that presided over the founding of western Indology as a scholarly discipline and as a part of a program of education. The book opens with a short Preface that delineates the aim of this publica- tion and provides necessary information about the archival sources. An extensive Introduction (1–21) offers short biographies of the two scholars, focusing, in particular, on the rise of their interest in classical Indian studies. The authors show that, quite amazingly, in spite of their very different biographical and educational backgrounds (Colebrooke never attended school and universi- ty in Europe, learning Sanskrit from traditional Indian scholars, while Schlegel obtained classical university education), both of them shared an inexhaustible interest in classical India, which arose, for both of them, due to quite fortuitous circumstances. -

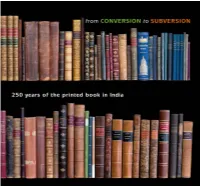

From Conversion to Subversion a Selection.Pdf

2014 FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India 2014 From Conversion to Subversion: 250 years of the printed book in India. A catalogue by Graham Shaw and John Randall ©Graham Shaw and John Randall Produced and published in 2014 by John Randall (Books of Asia) G26, Atlas Business Park, Rye, East Sussex TN31 7TE, UK. Email: [email protected] All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission in writing of the publisher and copyright holder. Designed by [email protected], Devon Printed and bound by Healeys Print Group, Suffolk FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India his catalogue features 125 works spanning While printing in southern India in the 18th the history of print in India and exemplify- century was almost exclusively Christian and Ting the vast range of published material produced evangelical, the first book to be printed in over 250 years. northern India was Halhed’s A Grammar of the The western technology of printing with Bengal Language (3), a product of the East India movable metal types was introduced into India Company’s Press at Hooghly in 1778. Thus by the Portuguese as early as 1556 and used inter- began a fertile period for publishing, fostered mittently until the late 17th century. The initial by Governor-General Warren Hastings and led output was meagre, the subject matter over- by Sir William Jones and his generation of great whelmingly religious, and distribution confined orientalists, who produced a number of superb to Portuguese enclaves. -

Jaina Studies

JAINA STUDIES Edited by Peter Flügel Volume 1 2016 Harrassowitz Verlag . Wiesbaden Johannes Klatt Jaina-Onomasticon Edited by Peter Flügel and Kornelius Krümpelmann 2016 Harrassowitz Verlag . Wiesbaden Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. For further information about our publishing program consult our website http://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de © Otto Harrassowitz GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden 2016 This work, including all of its parts, is protected by copyright. Any use beyond the limits of copyright law without the permission of the publisher is forbidden and subject to penalty. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. Printed on permanent/durable paper. Printing and binding: Hubert & Co., Göttingen Printed in Germany ISSN 2511-0950 ISBN 978-3-447-10584-2 Contents Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................. 7 Life and Work of Johannes Klatt ........................................................................................ 9 (by Peter -

Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation

Empire of Hope and Tragedy: Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Swain Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Timothy Gregory, Co-advisor Anthony Kaldellis Kristina Sessa, Co-advisor Copyright by Brian Swain 2014 Abstract This dissertation explores the intersection of political and ethnic conflict during the emperor Justinian’s wars of reconquest through the figure and texts of Jordanes, the earliest barbarian voice to survive antiquity. Jordanes was ethnically Gothic - and yet he also claimed a Roman identity. Writing from Constantinople in 551, he penned two Latin histories on the Gothic and Roman pasts respectively. Crucially, Jordanes wrote while Goths and Romans clashed in the imperial war to reclaim the Italian homeland that had been under Gothic rule since 493. That a Roman Goth wrote about Goths while Rome was at war with Goths is significant and has no analogue in the ancient record. I argue that it was precisely this conflict which prompted Jordanes’ historical inquiry. Jordanes, though, has long been considered a mere copyist, and seldom treated as an historian with ideas of his own. And the few scholars who have treated Jordanes as an original author have dampened the significance of his Gothicness by arguing that barbarian ethnicities were evanescent and subsumed by the gravity of a Roman political identity. They hold that Jordanes was simply a Roman who can tell us only about Roman things, and supported the Roman emperor in his war against the Goths. -

Indology-Studies in Germany

Indology-studies in Germany With special reference to Literature, ãgveda and Fire-Worship By Rita Kamlapurkar A thesis submitted towards the fulfilment for Degree of Ph.D. in Indology Under the guidance of Dr. Shripad Bhat And Co-Guidance of Dr. G. U. Thite Shri Bal Mukund Lohiya Centre Of Sanskrit And Indological Studies Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. December 2010. Acknowledgements : Achieving the ultimate goal while studying the Vedas might require many rebirths, as the ancient ãÈis narrate. In this scrutiny it has been tried to touch some droplets of this vast ocean of knowledge, as it’s a bold act with meagre knowledge. It is being tried to thank all those, who have extended a valuable hand in this task. I sincerely thank Dr. Shripad Bhat without whose enlightening, constant encouragement and noteworthy suggestions this work would not have existed. I thank Dr. G. U. Thite for his valuable suggestions and who took out time from his busy schedule and guided me. The constant encouragement of Dr. Sunanda Mahajan has helped me in completing this work. I thank the Librarian and staff of Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune, Maharashtra Sahitya Parishad, Pune and Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth for their help. I am very much grateful to Homa-Hof-Heiligenberg, Germany, its staff and Ms. Sirgun Bracht, for keeping the questionnaire regarding the Agnihotra-practice in the farm and helping me in collecting the data. My special thanks to all my German friends for their great help. Special thanks to Dr. Ulrich Berk and the Editorial staff of ‘Homanewsletter’ for their help. -

The Absent Vedas

The Absent Vedas Will SWEETMAN University of Otago The Vedas were first described by a European author in a text dating from the 1580s, which was subsequently copied by other authors and appeared in transla- tion in most of the major European languages in the course of the seventeenth century. It was not, however, until the 1730s that copies of the Vedas were first obtained by Europeans, even though Jesuit missionaries had been collecting Indi- an religious texts since the 1540s. I argue that the delay owes as much to the rela- tive absence of the Vedas in India—and hence to the greater practical significance for missionaries of other genres of religious literature—as to reluctance on the part of Brahmin scholars to transmit their texts to Europeans. By the early eighteenth century, a strange dichotomy was apparent in European views of the Vedas. In Europe, on the one hand, the best-informed scholars believed the Vedas to be the most ancient and authoritative of Indian religious texts and to preserve a monotheistic but secret doctrine, quite at odds with the popular worship of multiple deities. The Brahmins kept the Vedas, and kept them from those outside their caste, especially foreigners. One or more of the Vedas was said to be lost—perhaps precisely the one that contained the most sublime ideas of divinity. By the 1720s scholars in Europe had begun calling for the Vedas to be translated so that this secret doctrine could be revealed, and from the royal library in Paris a search for the texts of the Vedas was launched. -

The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character

The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character from 1778 to 1978 by Fiona Georgina Elisabeth Ross School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1988 ProQuest Number: 10731406 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10731406 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 20618054 2 The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character from 1778 to 1978 Abstract The thesis traces the evolution of the printed image of the Bengali script from its inception in movable metal type to its current status in digital photocomposition. It is concerned with identifying the factors that influenced the shaping of the Bengali character by examining the most significant Bengali type designs in their historical context, and by analyzing the composing techniques employed during the past two centuries for printing the script. Introduction: The thesis is divided into three parts according to the different methods of type manufacture and composition: 1. The Development of Movable Metal Types for the Bengali Script Particular emphasis is placed on the early founts which lay the foundations of Bengali typography. -

Englishes Today / September 2015 / Volume II, Issue I ISBN : 2395 - 4809

Englishes Today / September 2015 / Volume II, Issue I ISBN : 2395 - 4809 ENGLISHES TODAY I September 2015 I Vol. I, Issue II I ISSN : 2395 4809 EXECUTIVE BOARD OF EDITORS Dr. Mitul Trivedi Prof. Piyush Joshi President H M Patel Institute of English Training and Research, Gujarat, The Global Association of English Studies INDIA. Dr. Paula Greathouse Prof. Shefali Bakshi Prof. Karen Andresa Dr M Saravanapava Iyer Tennessee Technological Amity University, Lucknow Santorum University of Jaffna Univesity, Tennessee, UNITED Campus, University de Santa Cruz do Sul Jaffna, SRI LANKA STATES OF AMERICA Uttar Pradesh, INDIA Rio Grande do Sul, BRAZIL Dr. Rajendrasinh Jadeja Prof. Sulabha Natraj Dr. Julie Ciancio Former Director, Prof. Ivana Grabar Professor and Head, Waymade California State University, H M Patel Institute of English University North, College of Education, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Training and Research Varaždin, CROATIA Gujarat, INDIA Gujarat, INDIA Dr. Momtazur Rahman Dr. Bahram Moghaddas Prof. Amrendra K. Sharma International University of Dr. Ipshita Hajra Sasmal Khazar Institute of Higher Dhofar University Business Agriculture and University of Hyderabad Education, Salalah, Technology, Dhaka, Hyderabad, INDIA. Mazandaran, IRAN. SULTANATE OF OMAN BANGLADESH Prof. Ashok Sachdeva Prof. Buroshiva Dasgupta Prof. Syed Md Golam Faruk Devi Ahilya University West Bengal University of Technology, West King Khalid University Indore, INDIA Bengal, INDIA Assir, SAUDI ARABIA Englishes Today / September 2015 / Volume II, Issue I ISBN : 2395 - 4809 ENGLISHES TODAY I September 2015 I Vol. I, Issue II I ISSN : 2395 4809 ontents... C 01 Training as a Scaffolding Tool for Esl Professional Development Dr. N V Bose A Study of Unique Collocations in Indian English : An Outcome of Language Contact 02 Phenomenon Ritika Srivastava 03 Situate Words/sentences in Various Contexts to enhance reading & writing Amita Patel A Teacher’s Tale of Challenges and Difficulties Faced in Primary Level E.L.T. -

The Powers of Storytelling Women in Libro De Los Engaños De Las Mujeres

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE SPANISH SHAHRAZ D AND HER ENTOURAGE: THE POWERS OF STORYTELLING WOMEN IN LIBRO DE LOS ENGAÑOS DE LAS MUJERES Zennia Désirée Hancock, Doctor of Philosophy, 2004 Dissertation Directed By: Associate Professor Carmen Benito -Vessels Department of Spanish and Portuguese The anonymous Libro de los engaños e asayamientos de las mugeres (LEM ) is a collection of exempla consisting of a frame tale and twenty -three interpolated tales. It forms part of the Seven Sages/Sindib d cycle , shares source material with the Arabic Alf layla wa layla (A Thousand and One Nights ), and was ordered translated from Arabic into Romance by Prince Fadrique of Castile in 1253. In the text, females may be seen as presented according to the traditional archetypes of Eve and the Virgin Mary; however, the ambivalence of the work allows that it be interpreted as both misogynous and not, which complicates the straightforward designation of its female characters as “good” and bad.” Given this, th e topos of Eva/Ave as it applies to this text is re -evaluated. The reassessment is effected by exploring the theme of ambivalence and by considering the female characters as hybrids of both western and eastern tradition. The primary female character of the text, dubbed the “Spanish Shahraz d,” along with other storytelling women in the interpolated tales, are proven to transcend binary paradigms through their intellect, which cannot be said to be inherently either good or evil, and which is expressed through speech acts and performances. Chapter I reviews the historical background of Alfonsine Spain and the social conditions of medieval women, and discusses the portr ayal of females in literature, while Chapter II focuses on the history of the exempla, LEM , and critical approaches to the text, and then identifies Bakhtin’s theory of the carnivalesque and Judith Butler’s speech act theory of injurious language as appropriate methodologies, explaining how both are nuanced by feminist perspectives.