HRA-Hrr 2007 Book-EN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Alberta POD EPDF.Indd

WRITING ALBERTA: Aberta Building on a Literary Identity Edited by George Melnyk and Donna Coates ISBN 978-1-55238-891-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. If you want to reuse or distribute the work, you must inform its new audience of the licence terms of this work. -

At the Margins of the Habsburg Civilizing Mission 25

i CEU Press Studies in the History of Medicine Volume XIII Series Editor:5 Marius Turda Published in the series: Svetla Baloutzova Demography and Nation Social Legislation and Population Policy in Bulgaria, 1918–1944 C Christian Promitzer · Sevasti Trubeta · Marius Turda, eds. Health, Hygiene and Eugenics in Southeastern Europe to 1945 C Francesco Cassata Building the New Man Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy C Rachel E. Boaz In Search of “Aryan Blood” Serology in Interwar and National Socialist Germany C Richard Cleminson Catholicism, Race and Empire Eugenics in Portugal, 1900–1950 C Maria Zarimis Darwin’s Footprint Cultural Perspectives on Evolution in Greece (1880–1930s) C Tudor Georgescu The Eugenic Fortress The Transylvanian Saxon Experiment in Interwar Romania C Katherina Gardikas Landscapes of Disease Malaria in Modern Greece C Heike Karge · Friederike Kind-Kovács · Sara Bernasconi From the Midwife’s Bag to the Patient’s File Public Health in Eastern Europe C Gregory Sullivan Regenerating Japan Organicism, Modernism and National Destiny in Oka Asajirō’s Evolution and Human Life C Constantin Bărbulescu Physicians, Peasants, and Modern Medicine Imagining Rurality in Romania, 1860–1910 C Vassiliki Theodorou · Despina Karakatsani Strengthening Young Bodies, Building the Nation A Social History of Child Health and Welfare in Greece (1890–1940) C Making Muslim Women European Voluntary Associations, Gender and Islam in Post-Ottoman Bosnia and Yugoslavia (1878–1941) Fabio Giomi Central European University Press Budapest—New York iii © 2021 Fabio Giomi Published in 2021 by Central European University Press Nádor utca 9, H-1051 Budapest, Hungary Tel: +36-1-327-3138 or 327-3000 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ceupress.com An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched (KU). -

Serbia in 2001 Under the Spotlight

1 Human Rights in Transition – Serbia 2001 Introduction The situation of human rights in Serbia was largely influenced by the foregoing circumstances. Although the severe repression characteristic especially of the last two years of Milosevic’s rule was gone, there were no conditions in place for dealing with the problems accumulated during the previous decade. All the mechanisms necessary to ensure the exercise of human rights - from the judiciary to the police, remained unchanged. However, the major concern of citizens is the mere existential survival and personal security. Furthermore, the general atmosphere in the society was just as xenophobic and intolerant as before. The identity crisis of the Serb people and of all minorities living in Serbia continued. If anything, it deepened and the relationship between the state and its citizens became seriously jeopardized by the problem of Serbia’s undefined borders. The crisis was manifest with regard to certain minorities such as Vlachs who were believed to have been successfully assimilated. This false belief was partly due to the fact that neighbouring Romania had been in a far worse situation than Yugoslavia during the past fifty years. In considerably changed situation in Romania and Serbia Vlachs are now undergoing the process of self identification though still unclear whether they would choose to call themselves Vlachs or Romanians-Vlachs. Considering that the international factor has become the main generator of change in Serbia, the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia believes that an accurate picture of the situation in Serbia is absolutely necessary. It is essential to establish the differences between Belgrade and the rest of Serbia, taking into account its internal diversities. -

Disillusioned Serbians Head for China's Promised Land

Serbians now live and work in China, mostly in large cities like Beijing andShanghai(pictured). cities like inlarge inChina,mostly andwork live Serbians now 1,000 thataround andsomeSerbianmedia suggest by manyexpats offered Unofficial numbers +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 Belgrade in Concern Sparks Boom Estate Real Page 7 Issue No. No. Issue [email protected] 260 Friday, October 12 - Thursday, October 25,2018 October 12-Thursday, October Friday, Photo: Pixabay/shanghaibowen Photo: Skilled, adventurous young Serbians young adventurous Skilled, China – lured by the attractive wages wages attractive the by –lured China enough money for a decent life? She She life? adecent for money enough earning of incapable she was herself: adds. she reality,” of colour the got BIRN. told Education, Physical and Sports of ulty Fac Belgrade’s a MAfrom holds who Sparovic, didn’t,” they –but world real the change glasses would rose-tinted my thought and inlove Ifell then But out. tryit to abroad going Serbia and emigrate. to plan her about forget her made almost things These two liked. A Ivana Ivana Sparovic soon started questioning questioning soonstarted Sparovic glasses the –but remained “The love leaving about thought long “I had PROMISED LAND PROMISED SERBIANS HEAD HEAD SERBIANS NIKOLIC are increasingly going to work in in towork going increasingly are place apretty just than more Ljubljana: Page 10 offered in Asia’s economic giant. economic Asia’s in offered DISILLUSIONED love and had a job she ajobshe had and love in madly was She thing. every had she vinced con was Ana Sparovic 26-year-old point, t one FOR CHINA’S CHINA’S FOR - - - BELGRADE INSIGHT IS PUBLISHED BY INSIGHTISPUBLISHED BELGRADE for China. -

Publications Were Issued in Latin Or German

August 23–28, 2016 St. Petersburg, Russia EACS 2016 21st Biennial Conference of the European Association for Chinese Studies Book of ABStractS 2016 EACS- The European Association for Chinese Studies The European Association for Chinese Studies (EACS) is an international organization representing China scholars from all over Europe. Currently it has more than 700 members. It was founded in 1975 and is registered in Paris. It is a non-profit orga- nization not engaging in any political activity. The purpose of the Association is to promote and foster, by every possible means, scholarly activities related to Chinese Studies in Europe. The EACS serves not only as the scholarly rep- resentative of Chinese Studies in Europe but also as contact or- ganization for academic matters in this field. One of the Association’s major activities are the biennial con- ferences hosted by various centres of Chinese Studies in diffe- rent European countries. The papers presented at these confer- ences comprise all fields from traditional Sinology to studies of modern China. In addition, summer schools and workshops are organized under the auspices of the EACS. The Association car- ries out scholarly projects on an irregular basis. Since 1995 the EACS has provided Library Travel Grants to support short visits for research in major sinological libraries in Western Europe. The scheme is funded by the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation and destined for PhD students and young scholars, primarily from Eastern European countries. The EACS furthers the careers of young scholars by awarding a Young Scholar Award for outstanding research. A jury selects the best three of the submitted papers, which are then presented at the next bi-an- nual conference. -

Belgrade City Library

Innovative intersectoral partnerships best practices of the Belgrade City Library Marjan Marinkovic Assistant Director Belgrade City Library [email protected] The Belgrade City Library is the largest lending library in Serbia. It is a parent library for a network of 13 municipal libraries and their branches. Its holdings consist of almost 2.000.000 items, kept in 70 facilities with a total area of 13.000 square meters. BCL has more than 150,000 users. The Library has 240 employees. The Belgrade City Library network The Library has 70 facilities: 1 central building with 4 dislocated facilities, 13 municipal libraries with 50 branch libraries, and 2 separate children's departments. The Belgrade City Library - Central building Since October 1986, the Belgrade City Library has been located at 56 Knez Mihailova Street, in the former building of the hotel Srpska kruna. The hotel was constructed around 1867 and at that time was the most modern, elegant and best equipped hotel in Belgrade. BCL - Central building Reading room The Gallery Press conference hall Periodical department Municipal library Petar Kočić – one of the most beautiful libraries in the BCL network BCL - Central building The Roman Hall - one of the most popular cultural sites in town The Roman Hall is a unique space with an archaeological site in situ and a collection of stone fragments comprising sculptures, altars, Roman tombstones (stellas) and other stone art originating from the territory of Singidunum and the Danube-region of the province of Upper Mesia, created in the period between the 2nd and 4th century. The antique ambiance of the Roman Hall is a representative gathering point, where our citizens may attend numerous cultural programs that take place every day. -

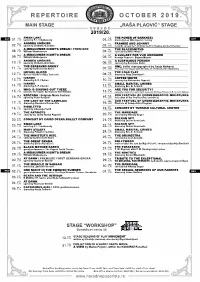

Repertoire October 2019

REPERTOIRE OCTOBER 2019. MAIN STAGE „RAŠA PLAOVIĆ“ STAGE season 2019/20. OCT TUE. SWAN LAKE TUE. THE POWER OF DARKNESS OCT 01. 7.30 ballet by P. I. Tchaikovsky 01. 8.30 drama by Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy WEN. ANDREA CHÉNIER THU. FRANKIE AND JOHNNY 02. 7.30 opera by Umberto Giordano 03. 8.30 romantic comedy by T. McNally, the NT in Belgrade and the NT Sombor TUE. A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM / PREMIERE FRI. THE BLACKSMITHS 08. 7.30 William Shakespeare 04. 8.30 comedy by Miloš Nikolić WEN. A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM SAT. A LULLABY FOR VUK UNKNOWN 09. 7.30 William Shakespeare 05. 8.30 Ksenija Popović / Bojana Mijović THU. ANDREA CHÉNIER SUN. A SUSPICIOUS PERSON 10. 7.30 opera by Umberto Giordano 06. 8.30 comedy by Branislav Nušić FRI. THE BEREAVED FAMILY MON. ONE, ballet choreographed by Sanja Ninković 11. 7.30 comedy by Branislav Nušić 07. 8.00 Encouragement Award 2018 (FESTIVAL OF CHOREOGRAPHIC MINIATURES) SAT. IMPURE BLOOD TUE. THE FOLK PLAY 12. 7.30 Borisav Stanković/Maja Todorović 08. 8.30 drama by Olga Dimitrijević SUN. IVANOV THU. COFFEE WHITE 13. 7.30 drama by A. P. Chekov 10. 8.30 comedy by Aleksandar Popović MON. IVANOV SAT. SMALL MARITAL CRIMES 14. 7.30 drama by A. P. Chekov 12. 8.30 drama by Eric E. Schmitt TUE. WHO IS SINGING OUT THERE SUN. ARE YOU FOR SECURITY? 15. 7.30 ballet to the music by Vojislav Voki Kostić 13. 8.30 a play after motifs from works by B. Jovanović, M. -

Human Rights, Democracy and – Violence HELSINKI COMMITTEE for HUMAN RIGHTS in SERBIA

HELSINKI COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN SERBIA SERBIA 2008 ANNUAL REPORT : SERBIA 2008 H HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND – VIOLENCE U M A N R I G H T S , D E M O C R A HHUMANUMAN RIGHTS,RIGHTS, C Y A N D – DDEMOCRACYEMOCRACY V I O L E N C E AANDND – VIOLENCEVIOLENCE Human Rights, Democracy and – Violence HELSINKI COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN SERBIA Annual Report: Serbia 2009 Human Rights, Democracy and – Violence BELGRADE, 2009 Annual Report: Serbia 2009 HUMAN RIGHTS, DEMOCRACY AND – VIOLENCE Publisher Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia On behalf of the publisher Sonja Biserko Translators Dragan Novaković Ivana Damjanović Vera Gligorijević Bojana Obradović Spomenka Grujičić typesetting – Ivan Hrašovec printed by Zagorac, Beograd circulation: 500 copies The Report is published with help of Swedish Helsinki Committee for Human Rights Swedish Helsinki Committee for Human Rights ISBN 978-86-7208-161-9 COBISS.SR–ID 167514380 CIP – Katalogizacija u publikaciji Narodna biblioteka Srbije, Beograd 323(497.11)”2008” 316.4(497.11) “2008” HUMAN Rights, Democracy and – Violence : Annual Report: Serbia 2008 / [prepared by] Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia; [translators Dragan Novaković ... et al.]. – Belgrade : Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, 2009 (Beograd : Zagorac). – 576 str. ; 23 cm Izv. stv. nasl. : Ljudska prava, demokratija i – nasilje. Tiraž 500. – Napomene i Bibliografske reference uz tekst. 1. Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji (Beograd) a) Srbija – Političke prilike – 2008 b) Srbija – Društvene prilike – 2008 5 Contents Conclusions and Recommendations . 9 No Consensus on System of Values . 17 I SOCIAL CONTEXT – XENOPHOBIA, RACISM AND INTOLERANCE Violence as a Way of Life . -

Tamara Berger Receptions.Pdf

Tamara Berger ECEPTIONS R OF ANCIENT EGYPT: A CASE STUDY COLLECTION Tamara Berger ______________________________________________________________ RECEPTIONS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: A CASE STUDY COLLECTION БИБЛИОТЕКА СТУДИЈЕ И ОГЛЕДИ Editor in Chief Nebojša Kuzmanović, PhD Editors Steffen Berger, Msc Kristijan Obšust, Msc Reviewers Professor José das Candeias Montes Sales, PhD, University Aberta, Lisbon Eleanor Dobson, PhD, University of Birmingham Susana Mota, PhD, Independant Researcher © Copyright: 2021, Arhiv Vojvodine Tamara Berger RECEPTIONS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: A CASE STUDY COLLECTION Novi Sad, 2021. For Steffen, Vincent and Theo RECEPTIONS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: A CASE STUDY COLLECTION 7 CONTENTS Introduction . 9 CHAPTER 1 Mnemohistories and Receptions of ancient Egypt in Serbia. 15 CHAPTER 2 Receptions of ancient Egypt in works of sculptor Ivan Meštrović and architect Jože Plečnik. 55 CHAPTER 3 Receptions of ancient Egypt in Ludwigsburg, the city of obelisks. 85 CHAPTER 4 Receptions of ancient Egypt in Weikersheim Palace: alchemy, obelisks and phoenixes . 129 CHAPTER 5 Saarbrücken, the city of stylistic chameleons. 151 CHAPTER 6 Stylistic mimicry and receptions: notes on the theoretical approach. 169 Reviews . .179 About the author. 185 RECEPTIONS OF ANCIENT EGYPT: A CASE STUDY COLLECTION 9 INTRODUCTION Roman emperor Hadrian, painter Paul Klee, neurologist Sigmund Freud, and plenty of others besides from ancient times up until the pres- ent have something in common: a great interest in ancient Egypt. There are many faces of this curiosity. Some have left traces of their interest in the form of collections of Egyptianized objects like Freud, who saw a common ground between psychoanalysis, which he founded, and archaeology, as they both search for deeper layers: one standing for personal memory and an- other for collective history.1 Some have purchased works of art that were made for them in “an Egyptian style”, and yet others, like architects, artists and writers, have produced their own works as acts of reception of ancient Egyptian art. -

FACULTY of ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY of BELGRADE

FACULTY Of ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF BELGRADE 75 yearsTRADITION AND DEVELOPMENT www.ekof.bg.ac.rs 75 godina Publisher University of Belgrade, Faculty of Economics Kamenička 6, phone 3021-045, fax 3021-065 www.ekof.bg.ac.rs E-mail: [email protected] For Publisher the Dean Prof. Marko Backović, PhD Editor Prof. Božidar Cerović, PhD Graphic design ČUGURA Print - Beograd [email protected] PrePress, Press, Postpress ČUGURA Print - Beograd www.cugura.rs Circulation 700 copies Year 2012 ISBN: 978-86-403-1242-4 Faculty of Economics 75 years Contents FIGURES ......................................................................................................11 A BRIEF HISTORY ........................................................................................ 13 MISSION ..................................................................................................... 18 TRADITION .................................................................................................22 Beginning (1937-1941) ................................................................................................. 22 War (1941-1944) ......................................................................................................... 25 Resumption of the HSEC Activities and the Founding of the Faculty of Economics (1944-1951) ......................................................................28 GROWTH ...................................................................................................30 Towards a Modern School (1952-1967) ...................................................................... -

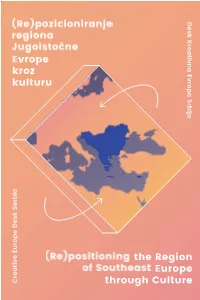

Reposition-1.Pdf

Introduction: Is every country too small for big ideas?1 Publication “(Re)positioning the region of Southeast Europe through culture” stems from the research conducted by the Creative Europe Desk Serbia within its Forum in 2017, the topic of which was exactly regional cooperation. Cre- ative Europe Forum 2018 shifts its focus on celebrating European cultural heritage, at the same time being related to the Republic of Bulgaria presiding over the Council of the European Union and dealing with EU integration of the Western Balkans. Due to this, an important segment of the CE Forum 2018 deals with regional cooperation in the feld of culture, and also cooperation of the region with the European Union. Bearing in mind the initiative of presiding over the EU Council has a clear political dimension, the debates during CE Forum 2018 will support future refections on the implementation of cultural strategy of the European Union. Our ambition is for the results presented in the publication “(Re)positioning the region of Southeast Europe through culture” to become a relevant segment in the implementation process of cultural strategy. The research was conducted in order to defne recommendations for the de- velopment of the region of Southeast Europe through culture. The aim was to analyse the presence of regional artists in relevant international manifesta- tions, the most important projects and initiatives from the domain of regional cooperation, strategic documents and legal frameworks of regional coopera- tion, and content of promotional touristic campaigns. The latter is especially important in the context of choosing content and the manner in which we present the region in the European and the international frameworks. -

288359384.Pdf

1• Lo1;1ghb_orough .Umverslty Pilkington Library Author/Filing Title ......~X.~~ ....................... .. ············ ............ ········· .................................. Vol. No. ............ Class Mark ..... ~ ................ Please note that fines are charged on ALL overdue items. Conspiracy theory in Serbian culture at the time of the Nato bombing of Yugoslavia by Jovan T. Byford © A doctoral thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of Loughborough University 19 March, 2002 r--~·------, Class ..,.r.,..· ...-oo~ c----·---Ace .......... No. Abstract The thesis examines Serbian conspiracy culture at the time of the Nato bombing of Yugoslavia in the spring of 1999. During the war, conspiratorial themes became a regular occurrence in Serbian mainstream media, as well as in pronouncements by the Serbian political establishment. For the most part, conspiratorial explanations focused on the machinations of transnational elite organisations such as the Bilderberg group or, more generally, on the conspiracy of 'the West'. However, conspiratorial accounts of the war occasionally invoked themes which were previously deemed to be beyond the boundaries of acceptable opinion, such as the allusion to a Jewish conspiracy or to the esoteric and occult aspects of the alleged plot. The thesis outlines the history of conspiracy theories in Serbia and critically reviews psychological approaches to understanding the nature of conspiracy theories. It suggests that the study of conspiratorial discourse requires the exploration of the rhetorical and argumentative structure of specific conspiratorial explanations, while paying special attention to the historical and ideological context within which these explanations are situated. The thesis is largely based upon the examination of the coverage of the war in the Serbian press.