Writing Alberta POD EPDF.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mayor Nenshi - Gift Log January 1 - June 30, 2019

Mayor Nenshi - Gift Log January 1 - June 30, 2019 Date From From (organization) To 7-Jan-19 Dan Pontefract Author Mayor 8-Jan-19 Jim Hutton Mayor 16-Jan-19 The Grand Mayor 17-Jan-19 Pumphouse Mayor 23-Jan-19 Front Row Theatre Mayor 24-Jan-19 Legion Mayor 25-Jan-19 Pumphouse Mayor 26-Jan-19 Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra Mayor 29-Jan-19 Theatre Calgary Mayor 30-Jan-19 Keeler School Mayor 30-Jan-19 Calgary Convention Centre Mayor 31-Jan-19 Susan Turner Daughters of the Niles & Shriners Mayor Hospital for Children 4-Feb-19 Mike Bezzeg Mayor 5-Feb-19 Arts Common Erin 6-Feb-19 Calgary Opera Mayor 9-Feb-19 Michelle Morin-Soyle Ville De Quebec Mayor 11-Feb-19 Kristy, Anika, Ashley Musicounts Mayor 11-Feb-19 Rebecca O'Brien, Karen Inglewood BIA Mayor Bray 12-Feb-19 Dr. Daniel Doz, Alberta University of the Arts Mayor President & CEO 13-Feb-19 Downstage Opening - Big Secret Mayor Theatre 19-Feb-19 Arts Common Mayor 21-Feb-19 City of Red Deer/Red Deer Canada Mayor Games 27-Feb-19 Calgary Arts Development Mayor 1-Mar-19 Ronna Goldbery All Seniors Cary Brenda/Mayor 12-Mar-19 ATP - Martha Cohen Theatre Mayor 12-Mar-19 Made By Momma Mayor 13-Mar-19 Lanre Ajayi Ethnik Fashion Mayor 18-Mar-19 Scott Crichton IBEW Local 424 Mayor 19-Mar-19 Rita Ferrara Calgary Transit Mayor 19-Mar-19 Molly Ann Kemp Mayor 20-Mar-19 Bureau de Visibilité de Calgary Mayor (BVC) 20-Mar-19 University of Calgary, Haskayne Mayor School of Business 21-Mar-19 Dr. -

Nationalism and Globalization / Le Nationalisme Et La

Editorial Board / Comité de rédaction Editor-in-Chief Rédacteur en chef Kenneth McRoberts, York University, Canada Associate Editors Rédacteurs adjoints Isabel Carrera Suarez, Universidad de Oviedo, Spain Daniel Salée, Concordia University, Canada Robert S. Schwartzwald, University of Massachusetts, U.S.A. Managing Editor Secrétaire de rédaction Guy Leclair, ICCS/CIEC, Ottawa, Canada Advisory Board / Comité consultatif Irene J.J. Burgers, University of Groningen, The Netherlands Patrick Coleman, University of California/Los Angeles, U.S.A. Enric Fossas, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, España Lois Foster, La Trobe University, Australia Fabrizio Ghilardi, Università di Pisa, Italia Teresa Gutiérrez-Haces, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico Eugenia Issraelian, Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia James Jackson, Trinity College, Republic of Ireland Jean-Michel Lacroix, Université de Paris III/Sorbonne Nouvelle, France Denise Gurgel Lavallée, Universidade do Estado da Bahia, Brésil Eugene Lee, Sookmyung University, Korea Erling Lindström, Uppsala University, Sweden Ursula Mathis, Universität Innsbruck, Autriche Amarjit S. Narang, Indira Gandhi National Open University, India Heather Norris Nicholson, University College of Ripon and York St. John, United Kingdom Satoru Osanai, Chuo University, Japan Vilma Petrash, Universidad Central de Venezuela-Caracas, Venezuela Danielle Schaub, University of Haifa, Israel Sherry Simon, Concordia University, Canada Wang Tongfu, Shanghai International Studies University, China International -

Writing the Terrain Travelling Through Alberta with the Poets Edited by Robert M

WRITING THE TERRAIN TRAVELLING THROUGH ALBERTA WITH THE POETS EDITED BY ROBERT M. STAMP PRESS n O z XI INTRODUCTION 1 WRITING THE PROVINCE i Barry McKinnon, untitled 3 Dennis Cooley, labiarinth 4 Joan Shillington, I Was Born Alberta 5 Nancy Holmes, The Right Frame of Mind 6 George Bowering, it's the climate 7 Charles Noble, Mnemonic Without Portfolio 8 John O. Thompson, Fuel Crisis 9 Robert Stamp, Energy to Burn 2 WRITING CALGARY 13 Ian Adam, In Calgary These Things 14 George Bowering, calgary 15 Murdoch Burnett, Boys or the River 17 Anne Campbell, Calgary City Wind 18 Weyman Chan, Written on Water 19 Ryan Fitzpatrick, From the Ogden Shops 21 Cecelia Frey, Under the Louise Bridge 22 Gail Ghai, On a Winter Hill Overlooking Calgary 23 Deborah Godin, Time/Lapse Calgary as Bremen 24 Vivian Hansen, Wolf Willow against the bridge 25 Robert Hilles, When Light Transforms Flesh 26 Nancy Holmes, Calgary Mirage 27 Bruce Hunter, Wishbone 28 Pauline Johnson, Calgary of the Plains 29 Robert Kroetsch, Horsetail Sonnet 30 Erin Michie, The Willows at Weaselhead 31 Deborah Miller, Pictures from the Stampede 33 James M. Moir, This City by the Bow 34 Colin Morton, Calgary '80 36 ErinMoure, South-West, or Altadore 40 Roberta Rees, Because Calgary 41 Robert Stamp, A City Built for Speed 42 Yvonne Trainer, 1912 43 Aritha van Herk, Quadrant Four - Outskirts of Outskirts 48 Wilfred Watson, In the Cemetery of the Sun 50 Christopher Wiseman, Calgary 2 A.M. 51 Rita Wong, Sunset Grocery • 3 WRITING SOUTHWESTERN ALBERTA & THE FOOTHILLS 55 D.C.Reid, Drying Out Again 56 Ian Adam, The Big Rocks 57 George Bowering, high river alberta 58 Cecelia Frey, Woman in a potato field north of Nanton 60 Sheri-D Wilson, He Went by Joe 62 Charles Noble, Props64 63 Stacie Wolfer, Lethbridge 65 Karen Solie, Java Shop, Fort Macleod 66 Sid Marty, Death Song for the Oldman 67 Michael Cullen, wind down waterton lakes 68 Ian Adam, Job Description 70 Jan Boydol, Color Hillcrest Dead 71 Aislinn Hunter, Frank Slide, Alberta 72 r. -

Ethnic Minority Writing: the Complexities Surrounding Authenticity, Translation, and Representation in a Global Environment

Ethnic Minority Writing: The Complexities Surrounding Authenticity, Translation, and Representation in a Global Environment Samuel Rose ※ Abstract: This paper discusses the complex issues surrounding authenticity and ethnic minority writing. It also addresses the broader global issues involved when an individual is educated in the West and then attempts to speak for his or her particular ethnic group. The paper concludes with a specifi c example regarding the complexities of translating a Japanese passage into English and discusses the little-known concept of “deterritorialization.” Key words: authenticity, ethnic minority writing, translation and representation, and deterritorialization Who is an authentic ethnic minority writer? How do we know if an individual truly has the authority to speak for his or her particular community? Does a Western education limit one’s ability to speak for his or her ethnic culture? If we assume that an individual does have the authority to speak for a particular group, can his or her writing be translated into another language and still retain the intended meaning? These are just a few of the questions that arise when discussing ethnic minority writing in Western nations. In this essay, I will use Joseph Pivato’s “Representation of Ethnicity as Problem: Essence or Construction” and attempt to answer the questions above. I will then conclude with an example that demonstrates just how complex the problems of representation in ethnic minority writing can be. Identifying with Minorities In the essay “Representation of Ethnicity as Problem: Essence or Construction,” Joseph Pivato writes, “I have often focussed on the voice of the writer and his/her authority to speak about the minority experi- ence” (Literary Pluralities, p. -

BIOGRAPHY of EMILY HAMPER "The Extremely Difficult Piano Part

BIOGRAPHY OF EMILY HAMPER "The extremely difficult piano part was perfectly realized by Emily Hamper, a very authoritative accompanist throughout the concert." (Concertonet, Paris, January 2014) Emily Hamper has earned an excellent reputation for her exceptional skills as a vocal coach and accompanist. Singers from her coaching studio perform with major opera companies and symphony orchestras around the world. Within an international career spanning twenty years, she has worked as a rehearsal pianist, coach, and assistant conductor for many prominent opera companies and organizations. Highly sought-after as a collaborator for voice recitals, she has recently appeared in performance for the Montreal Symphony Orchestra’s “Virée Classique”, L'Opéra National de Paris, and Music Toronto. In January 2017 she partners baritone Phillip Addis in recital at the Canadian Opera Company. Other performances include recitals for the Queensland Music Festival (Australia), Calgary Opera, Festival Orford, Stratford Summer Music, and many other venues in Canada, the USA, and Europe. In 2011 she was awarded the Best Collaborative Pianist Prize at the Eckhardt-Gramatté National Music Competition and accompanied thirteen performances across Canada on the National Winner's Tour. Performances have been broadcast on CBC Radio, Radio-Canada, Classical 96.3 FM and Vermont Public Radio. Engaged as a répétiteur and official audition accompanist by Calgary Opera, l'Opéra de Montréal, Opera Atelier and Pacific Opera Victoria, Ms. Hamper was production director for a performance based on Manon at the Muskoka Opera Festival in 2013. Her genuine interest in new music has resulted in engagements with Soundstreams Canada and Tapestry Opera, the workshopping of a new opera with Manitoba Opera, and the commission of a cycle of four songs by composer Erik Ross and poet Zachariah Wells. -

At the Margins of the Habsburg Civilizing Mission 25

i CEU Press Studies in the History of Medicine Volume XIII Series Editor:5 Marius Turda Published in the series: Svetla Baloutzova Demography and Nation Social Legislation and Population Policy in Bulgaria, 1918–1944 C Christian Promitzer · Sevasti Trubeta · Marius Turda, eds. Health, Hygiene and Eugenics in Southeastern Europe to 1945 C Francesco Cassata Building the New Man Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy C Rachel E. Boaz In Search of “Aryan Blood” Serology in Interwar and National Socialist Germany C Richard Cleminson Catholicism, Race and Empire Eugenics in Portugal, 1900–1950 C Maria Zarimis Darwin’s Footprint Cultural Perspectives on Evolution in Greece (1880–1930s) C Tudor Georgescu The Eugenic Fortress The Transylvanian Saxon Experiment in Interwar Romania C Katherina Gardikas Landscapes of Disease Malaria in Modern Greece C Heike Karge · Friederike Kind-Kovács · Sara Bernasconi From the Midwife’s Bag to the Patient’s File Public Health in Eastern Europe C Gregory Sullivan Regenerating Japan Organicism, Modernism and National Destiny in Oka Asajirō’s Evolution and Human Life C Constantin Bărbulescu Physicians, Peasants, and Modern Medicine Imagining Rurality in Romania, 1860–1910 C Vassiliki Theodorou · Despina Karakatsani Strengthening Young Bodies, Building the Nation A Social History of Child Health and Welfare in Greece (1890–1940) C Making Muslim Women European Voluntary Associations, Gender and Islam in Post-Ottoman Bosnia and Yugoslavia (1878–1941) Fabio Giomi Central European University Press Budapest—New York iii © 2021 Fabio Giomi Published in 2021 by Central European University Press Nádor utca 9, H-1051 Budapest, Hungary Tel: +36-1-327-3138 or 327-3000 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ceupress.com An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched (KU). -

Socialists, Populists, Policies and the Economic Development of Alberta and Saskatchewan

Mostly Harmless: Socialists, Populists, Policies and the Economic Development of Alberta and Saskatchewan Herb Emery R.D. Kneebone Department of Economics University of Calgary This Paper has been prepared for the Canadian Network for Economic History Meetings: The Future of Economic History, to be held at Guelph, Ontario, October 17-19, 2003. Please do not cite without permission of the authors. 1 “The CCF-NDP has been a curse on the province of Saskatchewan and have unquestionably retarded our economic development, for which our grandchildren will pay.”(Colin Thatcher, former Saskatchewan MLA, cited in MacKinnon 2003) In 1905 Wilfrid Laurier’s government established the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta with a border running from north to south and drawn so as to create two provinces approximately equal in area, population and economy. Over time, the political boundary has defined two increasingly unequal economies as Alberta now has three times the population of Saskatchewan and a GDP 4.5 times that of Saskatchewan. What role has the border played in determining the divergent outcomes of the two provincial economies? Factor endowments may have made it inevitable that Alberta would prosper relative to Saskatchewan. But for small open economies depending on external sources of capital to produce natural resources for export, government policies can play a role in encouraging or discouraging investment in the economy, especially those introduced early in the development process and in economic activities where profits are higher when production is spatially concentrated (agglomeration economies). Tax policies and regulations can encourage or discourage location decisions and in this way give spark to (or extinguish) agglomeration economies. -

Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing

UNIVERSITY PRESS <http://www.thepress.purdue.edu> CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb> Purdue University Press ©Purdue University The Library Series of the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access quarterly in the humanities and the social sciences CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture publishes scholarship in the humanities and social sciences following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the CLCWeb Library Series are 1) articles, 2) books, 3) bibliographies, 4) resources, and 5) documents. Contact: <[email protected]> Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweblibrary/canadianethnicbibliography> Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek, Asma Sayed, and Domenic A. Beneventi 1) literary histories and bibliographies of canadian ethnic minority writing 2) work on canadian ethnic minority writing This selected bibliography is compiled according to the following criteria: 1) Only English- and French-language works are included; however, it should be noted that there exists a substantial corpus of studies in a number Canada's ethnic minority languages; 2) Critical works about the literatures of Canada's First Nations are not included following the frequently expressed opinion that Canadian First Nations literatures should not be categorized within Canadian "Ethnic" writing but as a separate corpus; 3) Literary criticism as well as theoretical texts are included; 4) Critical texts on works of authors writing in English and French but usually viewed or which could be considered as "Ethnic" authors (i.e., immigré[e]/exile individuals whose works contain Canadian "Ethnic" perspectives) are included; 5) Some works dealing with US or Anglophone-American Ethnic Minority Writing with Canadian perspectives are included; 6) M.A. -

Serbia in 2001 Under the Spotlight

1 Human Rights in Transition – Serbia 2001 Introduction The situation of human rights in Serbia was largely influenced by the foregoing circumstances. Although the severe repression characteristic especially of the last two years of Milosevic’s rule was gone, there were no conditions in place for dealing with the problems accumulated during the previous decade. All the mechanisms necessary to ensure the exercise of human rights - from the judiciary to the police, remained unchanged. However, the major concern of citizens is the mere existential survival and personal security. Furthermore, the general atmosphere in the society was just as xenophobic and intolerant as before. The identity crisis of the Serb people and of all minorities living in Serbia continued. If anything, it deepened and the relationship between the state and its citizens became seriously jeopardized by the problem of Serbia’s undefined borders. The crisis was manifest with regard to certain minorities such as Vlachs who were believed to have been successfully assimilated. This false belief was partly due to the fact that neighbouring Romania had been in a far worse situation than Yugoslavia during the past fifty years. In considerably changed situation in Romania and Serbia Vlachs are now undergoing the process of self identification though still unclear whether they would choose to call themselves Vlachs or Romanians-Vlachs. Considering that the international factor has become the main generator of change in Serbia, the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia believes that an accurate picture of the situation in Serbia is absolutely necessary. It is essential to establish the differences between Belgrade and the rest of Serbia, taking into account its internal diversities. -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

Sheila Watson Fonds Finding Guide

SHEILA WATSON FONDS FINDING GUIDE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS JOHN M. KELLY LIBRARY | UNIVERSITY OF ST. MICHAEL’S COLLEGE 113 ST. JOSEPH STREET TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA M5S 1J4 ARRANGED AND DESCRIBED BY ANNA ST.ONGE CONTRACT ARCHIVIST JUNE 2007 (LAST UPDATED SEPTEMBER 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS TAB Part I : Fonds – level description…………………………………………………………A Biographical Sketch HiStory of the Sheila WatSon fondS Extent of fondS DeScription of PaperS AcceSS, copyright and publiShing reStrictionS Note on Arrangement of materialS Related materialS from other fondS and Special collectionS Part II : Series – level descriptions………………………………………………………..B SerieS 1.0. DiarieS, reading journalS and day plannerS………………………………………...1 FileS 2006 01 01 – 2006 01 29 SerieS 2.0 ManuScriptS and draftS……………………………………………………………2 Sub-SerieS 2.1. NovelS Sub-SerieS 2.2. Short StorieS Sub-SerieS 2.3. Poetry Sub-SerieS 2.4. Non-fiction SerieS 3.0 General correSpondence…………………………………………………………..3 Sub-SerieS 3.1. Outgoing correSpondence Sub-SerieS 3.2. Incoming correSpondence SerieS 4.0 PubliShing records and buSineSS correSpondence………………………………….4 SerieS 5.0 ProfeSSional activitieS materialS……………………………………………………5 Sub-SerieS 5.1. Editorial, collaborative and contributive materialS Sub-SerieS 5.2. Canada Council paperS Sub-SerieS 5.3. Public readingS, interviewS and conference material SerieS 6.0 Student material…………………………………………………………………...6 SerieS 7.0 Teaching material………………………………………………………………….7 Sub-SerieS 7.1. Elementary and secondary school teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.2. UniverSity of BritiSh Columbia teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.3. UniverSity of Toronto teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.4. UniverSity of Alberta teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.5. PoSt-retirement teaching material SerieS 8.0 Research and reference materialS…………………………………………………..8 Sub-serieS 8.1. -

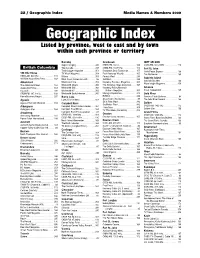

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance.