Chapter 10 Inverse Verbs and Other Syntactic Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

Kwakwaka'wakw Storytelling: Preserving Ancient Legends

MARCUS CHALMERS VERONIKA KARSHINA CARLOS VELASQUEZ KWAKWAKA'WAKW STORYTELLING: PRESERVING ANCIENT LEGENDS ADVISORS: SPONSOR: Professor Creighton Peet David Neel Dr. Thomas Balistrieri This report represents the work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely published these reports on its website without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, seehttp://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects Image: Neel D. (n.d.) Crooked Beak KWAKWAKA'WAKW i STORYTELLING Kwakwaka'wakw Storytelling: Reintroducing Ancient Legends An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science. Submitted by: Marcus Chalmers Veronika Karshina Carlos Velasquez Submitted to: David A. Neel, Northwest Coast native artist, author, and project sponsor Professor Creighton Peet Professor Thomas Balistrieri Date submitted: March 5, 2021 This report represents the work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely published these reports on its website without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects ABSTRACT ii ABSTRACT Kwakwaka'wakw Storytelling: Preserving Ancient Legends Neel D. (2021) The erasure of Kwakwaka'wakw First Nations' rich culture and history has transpired for hundreds of years. This destruction of heritage has caused severe damage to traditional oral storytelling and the history and knowledge interwoven with this ancient practice. Under the guidance of Northwest Coast artist and author David Neel, we worked towards reintroducing this storytelling tradition to contemporary audiences through modern media and digital technologies. -

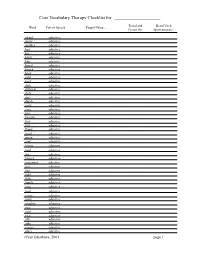

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

ALGONQUIAN TRADE LANGUAGES Richard Rhodes Eastern Ojibwa

1 ALGONQUIAN TRADE LANGUAGES Richard Rhodes Eastern Ojibwa Dictionary Project University of Michigan In this paper,1 I will turn from my more usual concerns of linguis tic analysis to a question of language use—a question of perhaps broader interest to the current audience since the implications of this paper touch on the domains of anthropology and ethnohistory as well as on linguistics. I will develop the hypothesis that intertribal contact among Algonquians in the Great Lakes area was mediated via trade languages or koines rather than through interpreters or by some other means.2 By the term trade language I mean a language customarily used for communication between speakers of different languages, even though it may be that neither speaker has the trade language as his dominant language. Some familiar examples include Greek, which in Roman times was the trade langauge of the Medi terranean, and Latin, which was the trade language of Europe. More recently Portuguese, French, and English have served as trade lan guages in various parts of Africa and Asia. Other well-known non- Indo-European trade languages include Swahili in East Africa and Fulani in West Africa, and one could argue that Modern Standard Arabic and Mandarin Chinese constitute trade languages in their respective parts of the world. It is characteristic of trade languages that there is a relatively high degree of bilingualism involving the trade language. As we will see later, this fact lends significant support to our position on Algonqui an trade languages. The hypothesis that certain midwestern Algonquian languages and dialects once served as trade languages arose out of an incongruity in my field work that has bothered me for a number of years, namely that most of the speakers of Ottawa that I have been working with are descendants not of Ottawas, but of Potawatomis and Chippewas, i.e. -

Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Linguistics, Program of 1981 Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ling_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Publication Info Published in Folia Linguistica Historica, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1981, pages 3-34. Disterheft, D. (1981). Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive. Folia Linguistica Historica, 2(1), 3-34. DOI: 10.1515/ flih.1981.2.1.3 © 1981 Societas Linguistica Europaea. This Article is brought to you by the Linguistics, Program of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foli.lAfl//ui.tfcoFolia Linguistica HfltorlcGHistorica II/III/l 'P'P.pp. 8-U3—Z4 © 800£etruSocietae lAngu,.ticaLinguistica Etlropaea.Evropaea, 1981lt)8l REMARKSBEMARKS ONON THETHE HISTORYHISTOKY OFOF THETHE INDO-EUROPEANINDO-EUROPEAN INFINITIVEINFINITIVE i DOROTHYDOROTHY DISTERHEFTDISTERHEFT I 1.1. INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION WithWith thethe exceptfonexception ofof Indo-IranianIndo-Iranian (Ur)(Hr) andand CelticCeltic allall historicalhistorical Indo-EuropeanIndo-European (IE)(IE) subgroupssubgroups havehave a morphologicalIymorphologically distinctdistinct II infinitive.Infinitive. However,However, nono singlesingle proto-formproto-form cancan bebe reconstructedreconstructed -

Navajo Verb Stem Position and the Bipartite Structure of the Navajo

678 REMARKSANDREPLIES NavajoVerb Stem Positionand the BipartiteStructure of the NavajoConjunct Sector Ken Hale TheNavajo verb stem appears at the rightmost edge of the verb word. Innumerouscases it forms a lexicalconstituent with a preverb,occur- ringat theleftmost edge of thesurface verb word, much in themanner ofDutchand German verb-particle arrangements in verb-secondfinite clauses.In Navajothe initial and finalpositions are separated by eight morphemeorder ‘ ‘slots’’ recognizedin the Athabaskan literature (and describedin detail for Navajo in Young and Morgan 1987). A phono- logicalsolution to this and a numberof otherdeep-surface disparities isexploredhere, based on theinsights of earlierworks on theNavajo verb,including Speas 1984, 1990, McDonough 1996, 2000, and Rice 1989, 2000. Keywords: verbmorphology, morphosyntactic disparity, spell-out, Navajo,Athabaskan 1Verb Stem Position TheNavajo verb stem forms asinglelexical constituent with the prefixal, particle-like category called preverb inthe Athabaskan linguistic literature (see Rice2000). However, like particle- verbcombinations in Dutchand German verb-second clauses, the parts of thisconstituent in the Navajocounterpart are separated in the surface forms ofverbal projections in syntax. In the Navajoversion of thisarrangement, the preverb occupies the leftmost position in the verb word, andthe verb stem occupies the rightmost position. TheNavajo verb in (1) canbe used to illustrate the phenomenon. The verb is segmented intoits various parts in (2), and the components are identified in slightly greater detail in (3). (1) Sila´o t’o´o´’go´o´ ch’´õ shidinõ´daøzh.(Young and Morgan 1987:283) ‘Thepoliceman jerked me outdoors (to get me out of afight).’ (2) ch’´õ sh d n-´ daøzh PreverbObject Qualifier Mode/ SubjVoice V (stem) Iwishto dedicate thisarticle totheNavajo Language Academy, asmall groupof linguists and teachers devotedto Navajolanguage research andeducation. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Education A COMPARATIVE SOCIO-HISTORICAL CONTENT ANALYSIS OF TREATIES AND CURRENT AMERICAN INDIAN EDUCATION LEGISLATION WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR THE STATE OF MICHIGAN A Thesis in Educational Leadership by Martin J. Reinhardt ©2004 Martin J. Reinhardt Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December, 2004 ii The thesis of Martin J. Reinhardt has been reviewed and approved by the following: John W. Tippeconnic III Professor of Education Thesis Advisor Chair of Committee William L. Boyd Batschelet Chair Professor of Education Susan C. Faircloth Assistant Professor of Education Edgar I. Farmer Professor of Education Nona A. Prestine Professor of Education In Charge of Graduate Programs in Educational Leadership *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT This study is focused on the relationship between two historical policy era of American Indian education--the Constitutional/Treaty Provisions Era and the Self- Determination/Revitalization Era. The primary purpose of this study is the clarification of what extent treaty educational obligations may be met by current federal K-12 American Indian education legislation. An historical overview of American Indian education policy is provided to inform the subsequent discussion of the results of a content analysis of sixteen treaties entered into between the United States and the Anishinaabe Three Fires Confederacy, and three pieces of federal Indian education legislation-the Indian Education Act (IEA), the Indian Self-Determination & Education Assistance Act (ISDEA), and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures …………………………………………………………………...... vii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………… ......... -

Unity and Diversity in Grammaticalization Scenarios

Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 16 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. ISSN: 2363-5568 Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language science press Walter Bisang & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). 2017. Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios (Studies in Diversity Linguistics -

Overt Pronouon Constraint Effects in Second Lanugage Japanese

Overt Pronoun Constraint effects in second language Japanese Tokiko Okuma Department of Linguistics McGill University Montreal, Quebec April 2, 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY © Copyright by Tokiko Okuma 2014 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the applicability of the Full Transfer/Full Access hypothesis (FT/FA) (Schwartz & Sprouse, 1994, 1996) by investigating the interpretation of the Japanese pronoun (kare ‘he’) by adult English and Spanish speaking learners of Japanese. The Japanese, Spanish, and English languages differ with respect to interpretive properties of pronouns. In Japanese and Spanish, overt pronouns disallow a bound variable interpretation in subject and object positions. By contrast, In English, overt pronouns may have a bound variable interpretation in these positions. This is called the Overt Pronoun Constraint (OPC) (Montalbetti, 1984). The FT/FA model suggests that the initial state of L2 grammar is the end state of L1 grammar and that the restructuring of L2 grammar occurs with L2 input. This hypothesis predicts that L1 English speakers of L2 Japanese would initially allow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions, transferring from their L1s. Nevertheless, they will successfully come to disallow a bound variable interpretation as their proficiency improves. In contrast, L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese would correctly disallow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions from the beginning. In order to test these predictions, L1 English and L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese at intermediate and advanced levels of proficiency were compared with native Japanese speakers in their interpretations of pronouns with quantified i antecedents in two tasks. -

Preverbs and Particles in Algonquian

Preverbs and Particles in Algonquian DAVID H. PENTLAND University of Manitoba In his comparative Algonquian sketch, Bloomfield (1946) distinguished three classes of words: nouns, verbs, and particles. Within the particle category he further distinguished pronouns (subdivided into personal pro nouns, demonstratives, indefinite pronouns, and interrogative pronouns), preverbs (defined as particles which freely precede verb stems, including some particles which never occur anywhere else), and prenouns (particles which similarly appear before nouns). Other scholars have found it useful to set up separate word classes of pronouns and numerals (e.g., Goddard & Bragdon 1988, Nichols & Nyholm 1995), and nowadays most Algonquianists treat preverbs and their kin as a separate category, rather than as a sub-class of particles. Beyond this there is little agreement. For example, in his sketch of Malecite-Passamaquoddy, Teeter (1971:203) divided the words we are concerned with into the categories prenoun, preverb and adverb - the last roughly equivalent to Bloom- field's particle. LeSourd (1993:8) more closely followed Bloomfield in stating that there are only three parts of speech, noun, verb and particle, but went on to note that there are also "loosely joined modifiers known as preverbs and prenouns" (LeSourd 1993:16) which may precede verb stems and noun stems, though he does not seem to have defined "modifier" in rela tion to the parts of speech. Leavitt (1985) introduced a distinction between "separate" preverbs and "attached" preverbs. However, in practice his "separate" preverbs include not only what others call preverbs, but also initial elements (i.e., "attached preverbs") which happen to be followed by an HI in derivation. -

Downloads/2010-Report-On-The-Status-Of-Bc-First- Nations-Languages.Pdf

Ḵ̓A̱NGEX̱TOLA SEWN-ON-TOP: KWAK’WALA REVITALIZATION AND BEING INDIGENOUS by PATRICIA CHRISTINE ROSBOROUGH B.A., University of Victoria, 1993 M.A., Bastyr University, 1995 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Educational Leadership and Policy) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2012 © Patricia Christine Rosborough, 2012 ABSTRACT Kwak’wala, the language of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw, like the languages of all Indigenous peoples of British Columbia, is considered endangered. Documentation and research on Kwak’wala began more than a century ago, and efforts to revitalize Kwak’wala have been under way for more than three decades. For Indigenous peoples in colonizing societies, language revitalization is a complex endeavour. Within the fields of language revitalization and Indigenous studies, the practices and policies of colonization have been identified as key factors in Indigenous language decline. This study deepens the understanding of the supports for and barriers to Kwak’wala revitalization. Emphasizing Indigenization as a key aspect of decolonization, the study explored the relationship between Kwak’wala learning and being Indigenous. The study was conducted through a Ḵ̓a̱ngex̱tola framework, an Indigenous methodology based on the metaphor of creating a button blanket, the ceremonial regalia of the Kwaka̱ka̱’wakw. The research has built understanding through the author’s experience as a Kwak’wala learner and the use of various approaches to language learning, including two years with the Master-Apprentice approach. The research employs the researcher’s journals and personal stories, as well as interviews with six individuals who are engaged in Kwak’wala revitalization. -

Morphology and Syntax of Gerunds in Truku Seediq : a Third Function of Austronesian “Voice” Morphology

MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX OF GERUNDS IN TRUKU SEEDIQ : A THIRD FUNCTION OF AUSTRONESIAN “VOICE” MORPHOLOGY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS SUMMER 2017 By Mayumi Oiwa-Bungard Dissertation Committee: Robert Blust, chairperson Yuko Otsuka, chairperson Lyle Campbell Shinichiro Fukuda Li Jiang Dedicated to the memory of Yudaw Pisaw, a beloved friend ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my most profound gratitude to the hospitality and generosity of the many members of the Truku community in the Bsngan and the Qowgan villages that I crossed paths with over the years. I’d like to especially acknowledge my consultants, the late 田信德 (Tian Xin-de), 朱玉茹 (Zhu Yu-ru), 戴秋貴 (Dai Qiu-gui), and 林玉 夏 (Lin Yu-xia). Their dedication and passion for the language have been an endless source of inspiration to me. Pastor Dai and Ms. Lin also provided me with what I can call home away from home, and treated me like family. I am hugely indebted to my committee members. I would like to express special thanks to my two co-chairs and mentors, Dr. Robert Blust and Dr. Yuko Otsuka. Dr. Blust encouraged me to apply for the PhD program, when I was ready to leave academia after receiving my Master’s degree. If it wasn’t for the gentle push from such a prominent figure in the field, I would never have seen the potential in myself.