Preverbs and Particles in Algonquian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

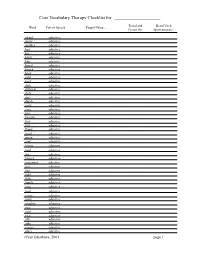

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Linguistics, Program of 1981 Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ling_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Publication Info Published in Folia Linguistica Historica, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1981, pages 3-34. Disterheft, D. (1981). Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive. Folia Linguistica Historica, 2(1), 3-34. DOI: 10.1515/ flih.1981.2.1.3 © 1981 Societas Linguistica Europaea. This Article is brought to you by the Linguistics, Program of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foli.lAfl//ui.tfcoFolia Linguistica HfltorlcGHistorica II/III/l 'P'P.pp. 8-U3—Z4 © 800£etruSocietae lAngu,.ticaLinguistica Etlropaea.Evropaea, 1981lt)8l REMARKSBEMARKS ONON THETHE HISTORYHISTOKY OFOF THETHE INDO-EUROPEANINDO-EUROPEAN INFINITIVEINFINITIVE i DOROTHYDOROTHY DISTERHEFTDISTERHEFT I 1.1. INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION WithWith thethe exceptfonexception ofof Indo-IranianIndo-Iranian (Ur)(Hr) andand CelticCeltic allall historicalhistorical Indo-EuropeanIndo-European (IE)(IE) subgroupssubgroups havehave a morphologicalIymorphologically distinctdistinct II infinitive.Infinitive. However,However, nono singlesingle proto-formproto-form cancan bebe reconstructedreconstructed -

Navajo Verb Stem Position and the Bipartite Structure of the Navajo

678 REMARKSANDREPLIES NavajoVerb Stem Positionand the BipartiteStructure of the NavajoConjunct Sector Ken Hale TheNavajo verb stem appears at the rightmost edge of the verb word. Innumerouscases it forms a lexicalconstituent with a preverb,occur- ringat theleftmost edge of thesurface verb word, much in themanner ofDutchand German verb-particle arrangements in verb-secondfinite clauses.In Navajothe initial and finalpositions are separated by eight morphemeorder ‘ ‘slots’’ recognizedin the Athabaskan literature (and describedin detail for Navajo in Young and Morgan 1987). A phono- logicalsolution to this and a numberof otherdeep-surface disparities isexploredhere, based on theinsights of earlierworks on theNavajo verb,including Speas 1984, 1990, McDonough 1996, 2000, and Rice 1989, 2000. Keywords: verbmorphology, morphosyntactic disparity, spell-out, Navajo,Athabaskan 1Verb Stem Position TheNavajo verb stem forms asinglelexical constituent with the prefixal, particle-like category called preverb inthe Athabaskan linguistic literature (see Rice2000). However, like particle- verbcombinations in Dutchand German verb-second clauses, the parts of thisconstituent in the Navajocounterpart are separated in the surface forms ofverbal projections in syntax. In the Navajoversion of thisarrangement, the preverb occupies the leftmost position in the verb word, andthe verb stem occupies the rightmost position. TheNavajo verb in (1) canbe used to illustrate the phenomenon. The verb is segmented intoits various parts in (2), and the components are identified in slightly greater detail in (3). (1) Sila´o t’o´o´’go´o´ ch’´õ shidinõ´daøzh.(Young and Morgan 1987:283) ‘Thepoliceman jerked me outdoors (to get me out of afight).’ (2) ch’´õ sh d n-´ daøzh PreverbObject Qualifier Mode/ SubjVoice V (stem) Iwishto dedicate thisarticle totheNavajo Language Academy, asmall groupof linguists and teachers devotedto Navajolanguage research andeducation. -

Unity and Diversity in Grammaticalization Scenarios

Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 16 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. ISSN: 2363-5568 Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language science press Walter Bisang & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). 2017. Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios (Studies in Diversity Linguistics -

Overt Pronouon Constraint Effects in Second Lanugage Japanese

Overt Pronoun Constraint effects in second language Japanese Tokiko Okuma Department of Linguistics McGill University Montreal, Quebec April 2, 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY © Copyright by Tokiko Okuma 2014 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the applicability of the Full Transfer/Full Access hypothesis (FT/FA) (Schwartz & Sprouse, 1994, 1996) by investigating the interpretation of the Japanese pronoun (kare ‘he’) by adult English and Spanish speaking learners of Japanese. The Japanese, Spanish, and English languages differ with respect to interpretive properties of pronouns. In Japanese and Spanish, overt pronouns disallow a bound variable interpretation in subject and object positions. By contrast, In English, overt pronouns may have a bound variable interpretation in these positions. This is called the Overt Pronoun Constraint (OPC) (Montalbetti, 1984). The FT/FA model suggests that the initial state of L2 grammar is the end state of L1 grammar and that the restructuring of L2 grammar occurs with L2 input. This hypothesis predicts that L1 English speakers of L2 Japanese would initially allow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions, transferring from their L1s. Nevertheless, they will successfully come to disallow a bound variable interpretation as their proficiency improves. In contrast, L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese would correctly disallow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions from the beginning. In order to test these predictions, L1 English and L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese at intermediate and advanced levels of proficiency were compared with native Japanese speakers in their interpretations of pronouns with quantified i antecedents in two tasks. -

Morphology and Syntax of Gerunds in Truku Seediq : a Third Function of Austronesian “Voice” Morphology

MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX OF GERUNDS IN TRUKU SEEDIQ : A THIRD FUNCTION OF AUSTRONESIAN “VOICE” MORPHOLOGY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS SUMMER 2017 By Mayumi Oiwa-Bungard Dissertation Committee: Robert Blust, chairperson Yuko Otsuka, chairperson Lyle Campbell Shinichiro Fukuda Li Jiang Dedicated to the memory of Yudaw Pisaw, a beloved friend ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my most profound gratitude to the hospitality and generosity of the many members of the Truku community in the Bsngan and the Qowgan villages that I crossed paths with over the years. I’d like to especially acknowledge my consultants, the late 田信德 (Tian Xin-de), 朱玉茹 (Zhu Yu-ru), 戴秋貴 (Dai Qiu-gui), and 林玉 夏 (Lin Yu-xia). Their dedication and passion for the language have been an endless source of inspiration to me. Pastor Dai and Ms. Lin also provided me with what I can call home away from home, and treated me like family. I am hugely indebted to my committee members. I would like to express special thanks to my two co-chairs and mentors, Dr. Robert Blust and Dr. Yuko Otsuka. Dr. Blust encouraged me to apply for the PhD program, when I was ready to leave academia after receiving my Master’s degree. If it wasn’t for the gentle push from such a prominent figure in the field, I would never have seen the potential in myself. -

Gros Ventre Student Grammar

1 Gros Ventre/White Clay Student Reference Grammar Vol. 1 Compiled by Andrew Cowell, based on the work of Allan Taylor, with assistance from Terry Brockie and John Stiffarm, Gros Ventre Tribe, Montana Published by Center for the Study of Indigenous Languages of the West (CSILW), University of Colorado Copyright CSILW First Edition, August 2012 Second Edition (revised by Terry Brockie), April 2013 Note: Permission is hereby granted by CSILW to all Gros Ventre individuals and institutions to make copies of this work as needed for educational purposes and personal use, as well as to institutions supporting the Gros Ventre language, for the same purposes. All other copying is restricted by copyright laws. 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction p. 3 2. Affirmative Statements p. 8 3. Non-Affirmative Statements p. 16 4. Commands p. 24 5. Background Statements p. 28 6. Nouns p. 38 7. Nouns from Verbs (Participles) p. 43 8. Modifying Verbs (Prefixes) p. 45 9. Using entire phrases as subjects, objects, p. 49 or verb modifiers (Complement and Adverbial Clauses) 10. Words that don’t change (Particles) p. 53 11. Numbers, Counting and Time p. 54 12. Appendix: Grammatical Abbreviations p. 55 13. Appendix: Grammar for Students of Gros Ventre p. 56 2 3 Gros Ventre Student Reference Grammar Vol. 1 Part One: Introduction Purpose of This Book This grammar is designed to be used by Gros Ventre students of the Gros Ventre/White Clay language. It is oriented primarily towards high school and college students and adult learners, rather than children. It will be easiest to use this grammar in conjunction with a class on the language, with a language teacher, but of course you can use it on your own as well. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Predicate Case Assignment in Russian Copular and Copula-Like Clauses Yuliya Kondratenko a Thesis In

A Syntactic Analysis of Predicate Case Assignment in Russian Copular and Copula-like Clauses Yuliya Kondratenko A Thesis in The Individualized Program Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts (Individualized Program) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2015 © Yuliya Kondratenko, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Yuliya Kondratenko Entitled: A Syntactic Analysis of Predicate Case Assignment in Russian Copular and Copula-like Clauses and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts complies with the regulations of this University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: _________________________________Chair Charles Reiss _________________________________Examiner Madelyn Kissock _________________________________Examiner Denis Liakin _________________________________Examiner Natalia Fitzgibbons _________________________________Thesis Supervisor Daniela Isac Approved________________________________________________________________ Graduate Program Director _______________ 20___ ______________________________ Dr. Paula Wood-Adams Dean of Graduate Studies iii Abstract A Syntactic Analysis of Predicate Case Assignment in Russian Copular and Copula-like Clauses Yuliya Kondratenko This thesis is about Case marking in predicational NPs and APs in Russian, meaning NPs and APs that occur after copular be and -

Latin Parts of Speech in Historical and Typological Context

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2014 Latin parts of speech in historical and typological context Viti, Carlotta Abstract: It is usually assumed that Latin parts of speech cannot be properly applied to other languages, especially outside the Indo-European domain. We will see, however, that the traditional distinction into eight parts of speech is established only in the late period of the classical school of grammar, while originally parts of speech varied in number and in type according to different grammarians, as well as to different periods and genres. Comparisons will be drawn on the one hand with parts of speech inthe Greek and Indian tradition, and on the other with genetically unrelated languages where parts of speech – notably adjectives and adverbs – are scarcely grammaticalized. This may be revealing of the manner in which the ancients used to categorize their language. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/joll-2014-0012 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-101955 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Viti, Carlotta (2014). Latin parts of speech in historical and typological context. Journal of Latin Linguistics, 13:279-301. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/joll-2014-0012 Journal of Latin Linguistics 2014; 13(2): 279 – 301 Carlotta Viti Latin parts of speech in historical and typological context Abstract: It is usually assumed that Latin parts of speech cannot be properly ap- plied to other languages, especially outside the Indo-European domain. -

The Preverb Eis- and Koine Greek Aktionsart

THE PREVERB EIS- AND KOINE GREEK AKTIONSART THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rachel Maureen Shain, B.A. * * * * * * * * The Ohio State University 2009 Approved By: Master’s Examination Committee: Dr. Brian Joseph, Advisor Dr. Judith Tonhauser, Advisor Dr. Craige Roberts Advisors Linguistics Graduate Program Copyright by Rachel Maureen Shain 2009 ABSTRACT This study analyzes one Koine Greek verb erchomai ‘go/come’ and one preverb eis- and how the preverb affects the verb’s lexical aspect. To determine the lexical aspect of erchomai and eis-erchomai, I annotate all instances of both verbs in the Greek New Testament and develop methodology for researching aktionsart in texts. Several tests for lexical aspect which might be applied to texts are proposed. Applying some of these tests to erchomai and eiserchomai, I determine that erchomai is an activity and eiserchomai is telic. A discussion of the Koine tense/aspect forms and their temporal and aspectual reference is included. I adopt Dowty’s 1979 aspect calculus to explain how eis- affects the lexical aspect of erchomai, using his CAUSE and BECOME operators to account for the meaning of eis-, which denotes an endpoint to motion such that the subject must be at a given location at the end of an interval over which eiserchomai is true. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe the completion of this thesis to several individuals and communities. My two advisers, Judith Tonhauser and Brian Joseph, contributed much time and energy to critiquing my thoughts and commenting on my drafts. -

The Algonquian Inverse Is Syntactic: Binding in Passamaquoddy∗

The Algonquian Inverse is Syntactic: Binding in Passamaquoddy∗ Benjamin Bruening, University of Delaware July 21, 2005 Abstract Treatments of the obviation and direct-inverse systems of Algonquian languages commonly invoke a participant hierarchy and re-linking of grammatical roles according to that hierarchy, or agreement that indexes that hierarchy directly. I show that positing this hierarchy is unnecessary: obviation depends on c-command, and the direct-inverse opposition is one of syntactic movement. I outline a theory that depends only on grammatical roles, c-command, and movement. This theory accounts straightforwardly for variable binding in Passamaquoddy, given the commonly invoked c-command condition on variable binding, where other theories make the wrong predictions. Moreover, in a complete theory of agreement in Algonquian, reference to syntactically encoded grammatical roles cannot be avoided. Since it is necessary to refer to syntax, both for agreement and for variable binding, the most parsimonious theory is one that refers only to syntax, and eschews a hierarchy of dubious status in the grammar, or the interaction of constraints on the alignment of such hierarchies. 1 Introduction The Algonquian languages, which have a voice system encoding a direct-inverse opposition rather than an active-passive opposition, have posed problems for theorists wanting to unify all languages under a single universal syntax (and morphology built off the syntax). On the other hand, they have provided ample fodder for theorists seeking discourse- or functional-based explanations for grammatical phenomena, who do not necessarily believe that all languages should have the same underlying formal structures and mechanisms. The pair of examples from Passamaquoddy in (1) illustrate the direct-inverse opposition.