A Comparison of Preverbs in Kutenai and Algonquian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward the Reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: the Algonquian-Wakashan 110-Item Wordlist

Sergei L. Nikolaev Institute of Slavic studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow/Novosibirsk); [email protected] Toward the reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: The Algonquian-Wakashan 110-item wordlist In the third part of my complex study of the historical relations between several language families of North America and the Nivkh language in the Far East, I present an annotated demonstration of the comparative data that was used in the lexicostatistical calculations to determine the branching and approximate glottochronological dating of Proto-Algonquian- Wakashan and its offspring; because of volume considerations, this data could not be in- cluded in the previous two parts of the present work and has to be presented autonomously. Additionally, several new Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan and Proto-Nivkh-Algonquian roots have been set up in this part of study. Lexicostatistical calculations have been conducted for the following languages: the reconstructed Proto-North Wakashan (approximately dated to ca. 800 AD) and modern or historically attested variants of Nootka (Nuuchahnulth), Amur Nivkh, Sakhalin Nivkh, Western Abenaki, Miami-Peoria, Fort Severn Cree, Wiyot, and Yurok. Keywords: Algonquian-Wakashan languages, Nivkh-Algonquian languages, Algic languages, Wakashan languages, Chimakuan-Wakashan languages, Nivkh language, historical phonol- ogy, comparative dictionary, lexicostatistics. The classification and preliminary glottochronological dating of Algonquian-Wakashan currently remain the same as presented in Nikolaev 2015a, Fig. 1 1. That scheme was generated based on the lexicostatistical analysis of 110-item basic word lists2 for one reconstructed (Proto-Northern Wakashan, ca. 800 A.D.) and several modern Algonquian-Wakashan lan- guages, performed with the aid of StarLing software 3. -

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

“Viewpoints” on Reconciliation: Indigenous Perspectives for Post-Secondary Education in the Southern Interior of Bc

“VIEWPOINTS” ON RECONCILIATION: INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVES FOR POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION IN THE SOUTHERN INTERIOR OF BC 2020 Project Synopsis By Christopher Horsethief, PhD, Dallas Good Water, MA, Harron Hall, BA, Jessica Morin, MA, Michele Morin, BSW, Roy Pogorzelski, MA September 1, 2020 Research Funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Executive Summary This research project synopsis presents diverse Indigenous community perspectives regarding the efforts needed to enable systemic change toward reconciliation within a public post-secondary educational institution in the Southern Interior of British Columbia. The main research question for this project was “How does a community college respectfully engage in reconciliation through education with the First Nations and Métis communities in the traditional territories in which it operates?” This research was realized by a team of six Indigenous researchers, representing distinct Indigenous groups within the region. It offers Indigenous perspectives, insights, and recommendations that can help guide post-secondary education toward systemic change. This research project was Indigenous led within an Indigenous research paradigm and done in collaboration with multiple communities throughout the Southern Interior region of British Columbia. Keywords: Indigenous-led research, Indigenous research methodologies, truth and reconciliation, Indigenous education, decolonization, systemic change, public post- secondary education in BC, Southern Interior of BC ii Acknowledgements This research was made possible through funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada. The important contributions from the Sinixt, Ktunaxa, Syilx, and Métis Elders, Knowledge Keepers, youth, men, and women within this project are essential to restoring important aspects of education that have been largely omitted from the public education system. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1983 Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians Cynthia J. Manning The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Manning, Cynthia J., "Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians" (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5855. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5855 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished m a n u s c r ip t in w h ic h c o p y r ig h t su b s i s t s . Any further r e p r in t in g of it s c o n ten ts must be a ppro ved BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD L ib r a r y Un iv e r s it y of Montana D a te : 1 9 8 3 AN ETHNOHISTORY OF THE KOOTENAI INDIANS By Cynthia J. Manning B.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1978 Presented in partial fu lfillm en t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1983 Approved by: Chair, Board of Examiners Fan, Graduate Sch __________^ ^ c Z 3 ^ ^ 3 Date UMI Number: EP36656 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

1- Project Background

11500 Coldstream Creek Road, Coldstream, BC, V1B 1E3 T: 250-777-3771 F: 250-542-0988 [email protected] www.ursus-heritage.ca November 30, 2020 Robin Annschild Wetland Restoration Consulting Victoria, BC RE: Archaeological Overview Assessment and Preliminary Field Reconnaissance of the proposed City of Trail Cambridge Creek Reservoir and Violin Lake Dam Decommissioning. This letter reports the findings of an archaeological overview assessment (AOA) and Preliminary Field Reconnaissance (PFR) of the proposed City of Trail Cambridge Creek Reservoir and Violin Lake Dam Decommissioning. The AOA and PFR were conducted at the request of Robin Annschild of Wetland Restoration Consulting on behalf of the City of Trail. The proposed dam decommissioning project is approximately 4 km south of Trail, BC and centers on Cambridge Creek Reservoir, located at the headwaters of Cambridge Creek, and the adjacent Violin Lake Reservoir, located at the headwaters of Goodeve Creek (Figure 1). The objectives of the AOA are to: •! Identify and evaluate any areas of archaeological potential within the subject exploration area that warrant detailed archaeological investigation; •! Provide recommendations regarding the need and appropriate scope of further archaeological studies. Archaeological sites can be defined as physical evidence of past human use of an area that, in the subject region, is typically represented by artifacts, lithic debitage (by-products of stone tool production), faunal remains, fire altered rock, hearth/fire pit features, and habitation and subsistence features. Project Background As outlined by Biebighauser and Annschild (2020), the Cambridge Creek and the Violin Lake Dams were originally constructed as part of a drinking water reservoir system for the City of Trail that operated from 1919 -1994. -

Published in Papers of the Twenty-Third Algonquian Conference, 1992, Edited by William Cowan

Published in Papers of the Twenty-Third Algonquian Conference, 1992, edited by William Cowan. Ottawa: Carleton University, pp. 119-163 A Comparison of the Obviation Systems of Kutenai and Algonquian Matthew S. Dryer SUNY at Buffalo 1. Introduction In recent years, the term ‘obviation’ has been applied to phenomena in a variety of languages on the basis of perceived similarity to the phenomenon in Algonquian languages to which, I assume, the term was originally applied. An example of a descriptive use of the term occurs in Dayley (1989: 136), who applies the terms ‘obviative’ and ‘proximate’ to two categories of demonstratives in Tümpisa Shoshone, the obviative category being used to introduce new information or to reference given participants which are nontopics, the proximate category for topics. But unlike the obviative and proximate categories of Algonquian languages, the Shoshone categories for which Dayley uses the terms are categories only of a class of words he calls ‘demonstratives’, and are not inflectional categories of nouns or verbs. Similarly, Simpson and Bresnan (1983) use the term ‘obviation’ to refer to a system in Warlpiri in which certain nonfinite verbs occur in forms that indicate that their subjects are nonsubjects in the matrix clause. These phenomena in non-Algonquian languages to which the term ‘obviation’ has been applied may bear some remote resemblance to the Algonquian phenomenon, but I suspect that most Algonquianists examining them would conclude that the resemblance is at best a remote one. The purpose of this paper is to describe an obviation system in Kutenai, a language isolate of southeastern British Columbia and adjacent areas of Idaho and Montana, and to compare it to the obviation system of Algonquian languages. -

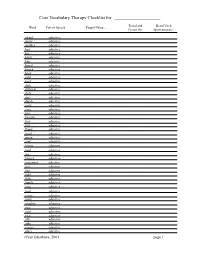

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Researching and Reviving the Unami Language of the Lenape

Endangered Languages, Linguistics, and Culture: Researching and Reviving the Unami Language of the Lenape By Maureen Hoffmann A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology and Linguistics Bryn Mawr College May 2009 Table of Contents Abstract........................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgments........................................................................................................... 4 List of Figures................................................................................................................. 5 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 II. The Lenape People and Their Languages .................................................................. 9 III. Language Endangerment and Language Loss ........................................................ 12 a. What is language endangerment?.......................................................................... 12 b. How does a language become endangered?.......................................................... 14 c. What can save a language from dying?................................................................. 17 d. The impact of language loss on culture ................................................................ 20 e. The impact of language loss on academia............................................................. 21 IV. -

Native American Tribes A

Native American Tribes A A'ananin (Aane), Abenaki (Abnaki, Abanaki, Abenaqui), Absaalooke (Absaroke), Achumawi (Achomawi), Acjachemen, Acoma, Agua Caliente, Adai, Ahtna (Atna), Ajachemen, Akimel O'odham, Akwaala (Akwala), Alabama-Coushatta, Aleut, Alutiiq, Algonquians (Algonkians), Algonquin (Algonkin), Alliklik, Alnobak (Alnôbak, Alnombak), Alsea (Älsé, Alseya), Andaste, Anishinaabe (Anishinabemowin, Anishnabay), Aniyunwiya, Antoniaño, Apache, Apalachee, Applegate, Apsaalo oke (Apsaroke), Arapaho (Arapahoe),Arawak, Arikara, Assiniboine, Atakapa, Atikamekw, Atsina, Atsug ewi (Atsuke), Araucano (Araucanian), Avoyel (Avoyelles), Ayisiyiniwok, Aymara, Aztec B Babine, Bannock, Barbareño, Bari, Bear River, Beaver, Bella Bella, Bella Coola, Beothuks (Betoukuag), Bidai, Biloxi, Black Carib, Blackfoot (Blackfeet), Blood Indians, Bora C Caddo (Caddoe), Cahita, Cahto, Cahuilla, Calapooya (Calapuya, Calapooia), Calusa (Caloosa), Carib, Carquin, Carrier, Caska, Catawba, Cathlamet, Cayuga, Cayus e, Celilo, Central Pomo, Chahta, Chalaque, Chappaquiddick (Chappaquiddic, Chappiquidic),Chawchila (Chawchilla), Chehalis, Chelan, Chemehuevi, Cheraw, Cheroenhaka (Cheroenkhaka, Cherokhaka), Cherokee, Chetco, Cheyenne (Cheyanne), Chickamaugan, Chickasaw, Chilcotin, Chilula- Wilkut, Chimariko, Chinook, Chinook Jargon, Chipewyan (Chipewyin), Chippewa, Chitimacha (Chitamacha), Chocheno, Choctaw, Cholon, Chontal de Tabasco (Chontal Maya), Choynimni (Choinimni), Chukchansi, Chumash, Clackamas (Clackama), Clallam, Clatskanie (Clatskanai), Clatsop, Cmique, Coastal -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Languages of the World--Native America

REPOR TRESUMES ED 010 352 46 LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD-NATIVE AMERICA FASCICLE ONE. BY- VOEGELIN, C. F. VOEGELIN, FLORENCE N. INDIANA UNIV., BLOOMINGTON REPORT NUMBER NDEA-VI-63-5 PUB DATE JUN64 CONTRACT MC-SAE-9486 EDRS PRICENF-$0.27 HC-C6.20 155P. ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS, 6(6)/1-149, JUNE 1964 DESCRIPTORS- *AMERICAN INDIAN LANGUAGES, *LANGUAGES, BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA, ARCHIVES OF LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD THE NATIVE LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS OF THE NEW WORLD"ARE DISCUSSED.PROVIDED ARE COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS AND DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LANGUAGES OF AMERICAN INDIANSNORTH OF MEXICO ANDOF THOSE ABORIGINAL TO LATIN AMERICA..(THIS REPOR4 IS PART OF A SEkIES, ED 010 350 TO ED 010 367.)(JK) $. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION nib Office ofEduc.442n MD WELNicitt weenment Lasbeenreproduced a l l e a l O exactly r o n o odianeting es receivromed f the Sabi donot rfrocestarity it. Pondsof viewor position raimentofficial opinions or pritcy. Offkce ofEducation rithrppologicalLinguistics Volume 6 Number 6 ,Tune 1964 LANGUAGES OF TEM'WORLD: NATIVE AMER/CAFASCICLEN. A Publication of this ARC IVES OF LANGUAGESor 111-E w oRLD Anthropology Doparignont Indiana, University ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS is designed primarily, butnot exclusively, for the immediate publication of data-oriented papers for which attestation is available in the form oftape recordings on deposit in the Archives of Languages of the World. This does not imply that contributors will bere- stricted to scholars working in the Archives at Indiana University; in fact,one motivation for the publication