Navajo Verb Stem Position and the Bipartite Structure of the Navajo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

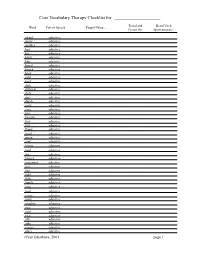

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Linguistics, Program of 1981 Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ling_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Publication Info Published in Folia Linguistica Historica, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1981, pages 3-34. Disterheft, D. (1981). Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive. Folia Linguistica Historica, 2(1), 3-34. DOI: 10.1515/ flih.1981.2.1.3 © 1981 Societas Linguistica Europaea. This Article is brought to you by the Linguistics, Program of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foli.lAfl//ui.tfcoFolia Linguistica HfltorlcGHistorica II/III/l 'P'P.pp. 8-U3—Z4 © 800£etruSocietae lAngu,.ticaLinguistica Etlropaea.Evropaea, 1981lt)8l REMARKSBEMARKS ONON THETHE HISTORYHISTOKY OFOF THETHE INDO-EUROPEANINDO-EUROPEAN INFINITIVEINFINITIVE i DOROTHYDOROTHY DISTERHEFTDISTERHEFT I 1.1. INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION WithWith thethe exceptfonexception ofof Indo-IranianIndo-Iranian (Ur)(Hr) andand CelticCeltic allall historicalhistorical Indo-EuropeanIndo-European (IE)(IE) subgroupssubgroups havehave a morphologicalIymorphologically distinctdistinct II infinitive.Infinitive. However,However, nono singlesingle proto-formproto-form cancan bebe reconstructedreconstructed -

Building Meaning in Navajo

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses March 2016 Building Meaning in Navajo Elizabeth A. Bogal-Allbritten University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Semantics and Pragmatics Commons Recommended Citation Bogal-Allbritten, Elizabeth A., "Building Meaning in Navajo" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 552. https://doi.org/10.7275/7646815.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/552 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUILDING MEANING IN NAVAJO A Dissertation Presented by ELIZABETH BOGAL-ALLBRITTEN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2016 Linguistics © Copyright by Elizabeth Bogal-Allbritten 2016 All Rights Reserved BUILDING MEANING IN NAVAJO A Dissertation Presented by ELIZABETH BOGAL-ALLBRITTEN Approved as to style and content by: Rajesh Bhatt, Chair Seth Cable, Member Angelika Kratzer, Member Margaret Speas, Member Alejandro Perez-Carballo, Member John Kingston, Head of Department Linguistics DEDICATION To my parents, Rose and Bill. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I thank the members of my committee. I came to the Univer- sity of Massachusetts because of my admiration for the work done by Rajesh Bhatt, Seth Cable, Angelika Kratzer, and Peggy Speas. That admiration has only grown during the dissertation process. I thank my chair, Rajesh Bhatt, who has been a tire- less mentor to me through all stages of my graduate career: from the first workshop, through the job market, and, of course, through the dissertation. -

MIXED CODES, BILINGUALISM, and LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requi

BILINGUAL NAVAJO: MIXED CODES, BILINGUALISM, AND LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Charlotte C. Schaengold, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Brian Joseph, Advisor Professor Donald Winford ________________________ Professor Keith Johnson Advisor Linguistics Graduate Program ABSTRACT Many American Indian Languages today are spoken by fewer than one hundred people, yet Navajo is still spoken by over 100,000 people and has maintained regional as well as formal and informal dialects. However, the language is changing. While the Navajo population is gradually shifting from Navajo toward English, the “tip” in the shift has not yet occurred, and enormous efforts are being made in Navajoland to slow the language’s decline. One symptom in this process of shift is the fact that many young people on the Reservation now speak a non-standard variety of Navajo called “Bilingual Navajo.” This non-standard variety of Navajo is the linguistic result of the contact between speakers of English and speakers of Navajo. Similar to Michif, as described by Bakker and Papen (1988, 1994, 1997) and Media Lengua, as described by Muysken (1994, 1997, 2000), Bilingual Navajo has the structure of an American Indian language with parts of its lexicon from a European language. “Bilingual mixed languages” are defined by Winford (2003) as languages created in a bilingual speech community with the grammar of one language and the lexicon of another. My intention is to place Bilingual Navajo into the historical and theoretical framework of the bilingual mixed language, and to explain how ii this language can be used in the Navajo speech community to help maintain the Navajo language. -

Unity and Diversity in Grammaticalization Scenarios

Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 16 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. ISSN: 2363-5568 Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language science press Walter Bisang & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). 2017. Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios (Studies in Diversity Linguistics -

Overt Pronouon Constraint Effects in Second Lanugage Japanese

Overt Pronoun Constraint effects in second language Japanese Tokiko Okuma Department of Linguistics McGill University Montreal, Quebec April 2, 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY © Copyright by Tokiko Okuma 2014 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the applicability of the Full Transfer/Full Access hypothesis (FT/FA) (Schwartz & Sprouse, 1994, 1996) by investigating the interpretation of the Japanese pronoun (kare ‘he’) by adult English and Spanish speaking learners of Japanese. The Japanese, Spanish, and English languages differ with respect to interpretive properties of pronouns. In Japanese and Spanish, overt pronouns disallow a bound variable interpretation in subject and object positions. By contrast, In English, overt pronouns may have a bound variable interpretation in these positions. This is called the Overt Pronoun Constraint (OPC) (Montalbetti, 1984). The FT/FA model suggests that the initial state of L2 grammar is the end state of L1 grammar and that the restructuring of L2 grammar occurs with L2 input. This hypothesis predicts that L1 English speakers of L2 Japanese would initially allow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions, transferring from their L1s. Nevertheless, they will successfully come to disallow a bound variable interpretation as their proficiency improves. In contrast, L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese would correctly disallow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions from the beginning. In order to test these predictions, L1 English and L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese at intermediate and advanced levels of proficiency were compared with native Japanese speakers in their interpretations of pronouns with quantified i antecedents in two tasks. -

Preverbs and Particles in Algonquian

Preverbs and Particles in Algonquian DAVID H. PENTLAND University of Manitoba In his comparative Algonquian sketch, Bloomfield (1946) distinguished three classes of words: nouns, verbs, and particles. Within the particle category he further distinguished pronouns (subdivided into personal pro nouns, demonstratives, indefinite pronouns, and interrogative pronouns), preverbs (defined as particles which freely precede verb stems, including some particles which never occur anywhere else), and prenouns (particles which similarly appear before nouns). Other scholars have found it useful to set up separate word classes of pronouns and numerals (e.g., Goddard & Bragdon 1988, Nichols & Nyholm 1995), and nowadays most Algonquianists treat preverbs and their kin as a separate category, rather than as a sub-class of particles. Beyond this there is little agreement. For example, in his sketch of Malecite-Passamaquoddy, Teeter (1971:203) divided the words we are concerned with into the categories prenoun, preverb and adverb - the last roughly equivalent to Bloom- field's particle. LeSourd (1993:8) more closely followed Bloomfield in stating that there are only three parts of speech, noun, verb and particle, but went on to note that there are also "loosely joined modifiers known as preverbs and prenouns" (LeSourd 1993:16) which may precede verb stems and noun stems, though he does not seem to have defined "modifier" in rela tion to the parts of speech. Leavitt (1985) introduced a distinction between "separate" preverbs and "attached" preverbs. However, in practice his "separate" preverbs include not only what others call preverbs, but also initial elements (i.e., "attached preverbs") which happen to be followed by an HI in derivation. -

The Burmese Monk

Through the Looking-Glass An American Buddhist Life Bhikkhu Cintita Copyright 2014, Bhikkhu Cintita (John Dinsmore) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported Licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work, Under the following conditions: • Attribution — You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). • Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. • No Derivative Works — You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. With the understanding that: • Waiver — Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. • Public Domain — Where the work or any of its elements is in the public domain under applicable law, that status is in no way affected by the license. • Other Rights — In no way are any of the following rights affected by the license: • Your fair dealing or fair use rights, or other applicable copyright exceptions and limitations; • The author's moral rights; • Rights other persons may have either in the work itself or in how the work is used, such as publicity or privacy rights. • Notice — For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Publication Data. Bhikkhu Cintita (John Dinsmore, Ph.D.), 1949 - Through the Looking Glass: An American Buddhist Life/ Bhikkhu Cintita. 1.Buddhism – Biography. © 2014. Cover design by Kymrie Dinsmore. Photo: Ashin Paññasīha and Ashin Cintita with lay devotees in Yangon in 2010. -

Newsletter Xxvi:2

THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF THE INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES OF THE AMERICAS NEWSLETTER XXVI:2 July-September 2007 Published quarterly by the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Lan- SSILA BUSINESS guages of the Americas, Inc. Editor: Victor Golla, Dept. of Anthropology, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521 (e-mail: golla@ ssila.org; web: www.ssila.org). ISSN 1046-4476. Copyright © 2007, The Chicago Meeting SSILA. Printed by Bug Press, Arcata, CA. The 2007-08 annual winter meeting of SSILA will be held on January 3-6, 2008 at the Palmer House (Hilton), Chicago, jointly with the 82nd Volume 26, Number 2 annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America. Also meeting concur- rently with the LSA will be the American Dialect Society, the American Name Society, and the North American Association for the History of the CONTENTS Language Sciences. The Palmer House has reserved blocks of rooms for those attending the SSILA Business . 1 2008 meeting. All guest rooms offer high speed internet, coffee makers, Correspondence . 3 hairdryers, CD players, and personalized in-room listening (suitable for Obituaries . 4 iPods). The charge for (wired) in-room high-speed internet access is $9.95 News and Announcements . 9 per 24 hours; there are no wireless connections in any of the sleeping Media Watch . 11 rooms. (The lobby and coffee shop are wireless areas; internet access costs News from Regional Groups . 12 $5.95 per hour.) The special LSA room rate (for one or two double beds) Recent Publications . 15 is $104. The Hilton reservation telephone numbers are 312-726-7500 and 1-800-HILTONS. -

Morphology and Syntax of Gerunds in Truku Seediq : a Third Function of Austronesian “Voice” Morphology

MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX OF GERUNDS IN TRUKU SEEDIQ : A THIRD FUNCTION OF AUSTRONESIAN “VOICE” MORPHOLOGY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS SUMMER 2017 By Mayumi Oiwa-Bungard Dissertation Committee: Robert Blust, chairperson Yuko Otsuka, chairperson Lyle Campbell Shinichiro Fukuda Li Jiang Dedicated to the memory of Yudaw Pisaw, a beloved friend ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my most profound gratitude to the hospitality and generosity of the many members of the Truku community in the Bsngan and the Qowgan villages that I crossed paths with over the years. I’d like to especially acknowledge my consultants, the late 田信德 (Tian Xin-de), 朱玉茹 (Zhu Yu-ru), 戴秋貴 (Dai Qiu-gui), and 林玉 夏 (Lin Yu-xia). Their dedication and passion for the language have been an endless source of inspiration to me. Pastor Dai and Ms. Lin also provided me with what I can call home away from home, and treated me like family. I am hugely indebted to my committee members. I would like to express special thanks to my two co-chairs and mentors, Dr. Robert Blust and Dr. Yuko Otsuka. Dr. Blust encouraged me to apply for the PhD program, when I was ready to leave academia after receiving my Master’s degree. If it wasn’t for the gentle push from such a prominent figure in the field, I would never have seen the potential in myself. -

Appendixa: Navajo Wordlists

APPENDIX A: NAVAJO WORDLISTS Compiled by : Martha Austin-Garrison, Navajo Community College, Shiprock NM Joyce McDonough, University ofRochester, Rochester, NY These word lists were constructed to exemplify different aspects of the sound system, such as the phonemic contrasts, tonal contrasts within words, the distinction between sounds as they appear in the stem versus conjunct and disjunct domains, and differences in the sizes of the domains in the word. Wordlist 1: Phonemic Contrasts This word list was constructed to investigate the phonemic contrasts in Navajo, as we could identify them. Because of the constraints on the sound system imposed by the morphology, the contrasts of the phonemic inventory are confined to the stem morpheme. Since the language is heavily verbal , and since verbs have a distinct structure with many distributional constraints, the notion minimal pairs, as we are used to thinking of them, are difficult to find . We chose to use prefixed nouns in this list. To get as consistent an environment as possible, the 3rd singular possessive prefix bi / [pI] 'her/his/one 's' was used with nouns . In some cases this produced words that were semantically awkward or anomalous for native speakers ('one's water' for instance). But the word list was checked with speakers before the recording session and we did not use words that speakers were uncomfortable with . I did not use tokens containing speech errors or distluencies in the analyses. Thus not all words are spoken by all speakers, and some words were dropped altogether. Some of the spelling conventions in these word lists are different from those used in Young and Morgan .