Gros Ventre Student Grammar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Following Interview Was Conducted , with Eisa Zayada for Star City Treasures Americorps Oral History Project

The following interview was conducted , with Eisa Zayada for Star City Treasures AmeriCorps Oral History Project. It took place on March 29, 2007 at “F” Street Rec Center. The interviewer is Julie Frith. JULIE: So, you want to tell me a little bit about where you grew up? EISA: Hmm. Uh, I was born in Khartoum. Khartoum is located in western Sudan, which is in Darfur province. I grew up there and Khartoum is actually not very big town, is a small town of about 200,000 people. You want me to go further, or that is it? JULIE: No, you can keep talking. Whatever you want to do. EISA: Do you want me to describe the area? JULIE: If you want to, sure. EISA: Khartoum itself? JULIE: Sure. EISA: Well, Khartoum is very nice and interesting town. And Khartoum has good - it has like, small market, which is like people come and sell you their things. Like, small things [unintelligible]. And, it’s kind of - people come from different places, like Qurma, Khartoum, [unintelligible]. And they sell their things - they sell their sheep, sell their things which you grow up there. And then, I like the place because it is among mountains. In the autumn, it was very, very beautiful. Became green, and the trees became green - it’s like here now, which is in summer. JULIE: So, like how far would people have to travel to go to the marketplace? EISA: Well, it’s like from [unintelligible], which is - I mean, the village which is also I know, Qatar, it’s sixteen miles. -

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

Greek Grammar Review

Greek Study Guide Some Step-by-Step Translation Issues I. Part of Speech: Identify a word’s part of speech (noun, pronoun, adjective, verb, adverb, preposition, conjunction, particle, other) and basic dictionary form. II. Dealing with Nouns and Related Forms (Pronouns, Adjectives, Definite Article, Participles1) A. Decline the Noun or Related Form 1. Gender: Masculine, Feminine, or Neuter 2. Number: Singular or Plural 3. Case: Nominative, Genitive, Dative, Accusative, or Vocative B. Determine the Use of the Case for Nouns, Pronouns, or Substantives. (Part of examining larger syntactical unit of sentence or clause) C. Identify the antecedent of Pronouns and the referent of Adjectives and Participles. 1. Pronouns will agree with their antecedent in gender and number, but not necessarily case. 2. Adjectives/participles will agree with their referent in gender, number, and case (but will not necessary have the same endings). III. Dealing with Verbs (to include Infinitives and Participles) A. Parse the Verb 1. Tense/Aspect: Primary tenses: Present, Future, Perfect Secondary (past time) tenses: Imperfect, Aorist, Pluperfect 2. Mood: Moods: Indicative, Subjunctive, Imperative, or Optative Verbals: Infinitive or Participle [not technically moods] 3. Voice: Active, Middle, or Passive 4. Person: 1, 2, or 3. 5. Number: Singular or Plural Note: Infinitives do not have Person or Number; Participles do not have Person, but instead have Gender and Case (as do nouns and adjectives). B. Review uses of Infinitives, Participles, Subjunctives, Imperatives, and Optatives before translating these. C. Review aspect before translating any verb form. · See p. 60 in FGG (3rd and 4th editions) to translate imperfects and all present forms. -

Brighton Museum & Art Gallery | 20 July 2017 to 3 June 2018

Brighton Museum & Art gallery | 20 July 2017 to 3 June 2018 Hand embroidered sampler, 2017 Hand embroidered sampler, MUSEUM OF TRANSOLOGY We are proud to present Museum of Transology. This exhibition is part of Be Bold, a programme created and developed together with our LGBTQ communities. Be Bold reflects the ways they would like to work with Royal Pavilion & Museums, bringing their voices, experiences and histories into the museum in their own words. Museum of Transology is curated by E-J Scott. It will take you on a journey with trans community individuals who share their honest, unedited experiences. The display deals with themes of the body, gender and identity. Please be aware that some objects are of a sensitive nature. Visitors may The UK’s trans communities are The Museum of Transology is have a personal response which connects to increasingly vibrant, visible dedicated to giving a voice to the their own experience and lives; there are links and confident about sharing reality of trans lives and halting for support and contact groups for issues our stories. Trans people are the erasure of transcestry. The raised within the display, and this can be found coming out, finding each other collection is as diverse as the in the gallery folders. and organising Pride events, and trans experience itself, yet shares Brighton & Hove continues to themes of hope, despair, ambition, Parents and carers are responsible for pave the way in the fight for trans confidence and desire. It began by supervising children’s visit to this exhibition. acceptance and equality. Trans gathering objects and stories from people’s gender identities are self- the local trans community at the defined. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Student's Quick Guide to Grammar Terms

Oxford Spanish Dictionary Skills Resource Pack Oxford Spanish Dictionary Skills Resource Pack Glossary H Review and questions Abbreviation A shortened form of a word Conjunction conj A word used to join indirectly affected by the verb: le escribí or phrase: Sr. = Mr clauses together: y = and; pero = but; una carta a mi madre = I wrote a letter to porque = Active In the active form the subject of the because my mother Finally, a brief review of the topics covered in the lecture: verb performs the action: Pedro besa a Consonant All the letters of the alphabet Indirect speech A report of what someone Ana = Pedro kisses Ana. See Passive. other than a, e, i, o, u has said which does not reproduce the • Important factors to bear in mind when choosing a bilingual [show slide 35] Adjectival phrase loc adj A phrase that Countable (count) noun [C] A noun that exact words: dijo que habían salido = she dictionary functions as an adjective: a ultranza = out- forms a plural and can take the indefinite said that they had gone out; he told me to • Navigating through an entry – English-Spanish, then Spanish-English and-out, fanatical; es nacionalista a article, e.g. a book, two books. See be quiet = me dijo que me callara ultranza = o Uncountable noun. he's a fanatical out-and-out Infinitive The base form of a verb: cantar = • Explaining abbreviations and symbols: nationalist, he's a nationalist through-and- Definite article def art: el/la/los/las = the to sing - common grammatical categories through Demonstrative adjective adj dem An Inflect To change -

250 Word List

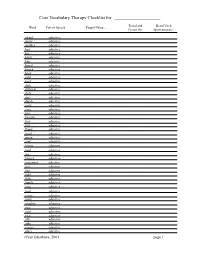

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Atajo Workshops Outline

Atajo for Students Atajo Basics: What does Atajo do? • Atajo is a reference keep Atajo open on the side of the computer while writing or studying in Spanish. • Dictionary search in either Spanish or English, see definition in opposite language, audio, examples and related links if available. • Verb Conjugator see correct conjugation in all tenses. If you’ve clicked on a word in Dictionary tab, it will automatically display when you go to Verb Conjugator. Click on the name of the tense to see detailed conjugation for all possible subjects (yo, tú, etc.). • Grammar read explanation and examples for grammar topics. • Vocabulary see words grouped by topic—useful for extending your vocabulary and finding synonyms or more precise words. • Phrases find expressions appropriate to use in different situations. Note: vocabulary tends to be casual rather than academic. • Search search within all of the above. • Accent Tool handy for inserting accented characters (or use keyboard shortcuts). • Help besides instructions for using the software, the Help document also lists all the abbreviations used in the dictionary (e.g., “nm” = “masculine noun”). Using Atajo to Develop Your Spanish Proficiency When writing (or preparing to speak): • Use search to look up words you’re not 100% sure of spelling, meaning, or pronunciation. • Check meanings in both languages to help you understand the connotation and ensure you’ve chosen the most appropriate word. • Reviewing the related topics in Vocabulary and Phrases can also help you to determine if your word usage is appropriate and discover more word options to choose from. • Check conjugation of verbs and subject-verb agreement. -

Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Linguistics, Program of 1981 Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ling_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Publication Info Published in Folia Linguistica Historica, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1981, pages 3-34. Disterheft, D. (1981). Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive. Folia Linguistica Historica, 2(1), 3-34. DOI: 10.1515/ flih.1981.2.1.3 © 1981 Societas Linguistica Europaea. This Article is brought to you by the Linguistics, Program of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foli.lAfl//ui.tfcoFolia Linguistica HfltorlcGHistorica II/III/l 'P'P.pp. 8-U3—Z4 © 800£etruSocietae lAngu,.ticaLinguistica Etlropaea.Evropaea, 1981lt)8l REMARKSBEMARKS ONON THETHE HISTORYHISTOKY OFOF THETHE INDO-EUROPEANINDO-EUROPEAN INFINITIVEINFINITIVE i DOROTHYDOROTHY DISTERHEFTDISTERHEFT I 1.1. INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION WithWith thethe exceptfonexception ofof Indo-IranianIndo-Iranian (Ur)(Hr) andand CelticCeltic allall historicalhistorical Indo-EuropeanIndo-European (IE)(IE) subgroupssubgroups havehave a morphologicalIymorphologically distinctdistinct II infinitive.Infinitive. However,However, nono singlesingle proto-formproto-form cancan bebe reconstructedreconstructed -

Gros Ventre, Piegan, Blood, Blackfeet, and River Crow Indians, in Montana

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 1-24-1888 Gros Ventre, Piegan, Blood, Blackfeet, and River Crow Indians, in Montana. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation H.R. Rep. No. 104, 50th Cong., 1st Sess. (1888) This House Report is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 50TH CoxGRESS, t HOUSE OF REPRESE:NT1\..TIYES. j REOPRT 1st Session. f { No. 104. GROS VENTRg, PIEGAX, BLOOD, BLACKFEET, AND RIVER CHO\V r:,DIANS, IN 1\IO~TANA. JAXUARY ~4, 1~88.-Counuittefl to the Committee of the "\'{hole House ou the state of tlw "Guion and ordered to he printed. 1\Ir. HARE, from the Committee on Indian Affairs, submitted the fol lowing REPORT: [To accomp:uw Lill H. R. lp;)(,.] The Comrnittee on Indian A.tfai'rs, to 'lchom 'leas refer;·red the bill (H. R. J 956) to rat'ifY and con.finn an agreement with the Gros Yentre, Piegan, Blood, Blackfeet, cmd R'iiJer Crow Indians, rn Jllontana, respectfully r;·e port: That they have given the same a full and careful consideration, and unanimously recommend the passage of the same, with the following amenumeuts: First, strike out the word "J os~ph" where it appears in line 1, page 1, and insert the word "John" in lieu thereof. -

Wisconsin Motorists Handbook

Motorists’ Handbook WISCONSIN DEPARAugustTMENT 2021 OF TRANSPORTATION August 2021 CONTENTS CONTENTS PRELIMINARY INFORMATION 1 BEFORE YOU DRIVE 10 Address change 1 Plan ahead and save fuel 10 Obtain services online 1 Check the vehicle 10 Obtain information 1 Clean glass surfaces 12 Consider saving a life Adjust seat and mirrors 12 by becoming an organ donor 2 Use safety belts and child restraints 13 Absolute sobriety 2 Wisconsin Graduated Driver Licensing RULES OF THE ROAD 15 Supervised Driving Log, HS-303 2 Traffic control devices 15 This manual 2 TRAFFIC SIGNALS 16 DRIVER LICENSE 2 Requirements 3 TRAFFIC SIGNS 18 Carrying the driver license and license Warning signs 18 replacement 4 Regulatory signs 20 Out of state transfers 4 Railroad crossing warning signs 23 Construction signs 25 INSTRUCTION PERMIT 5 Guide signs 25 Restrictions of the instruction permit 6 PAVEMENT MARKINGS 26 PROBATIONARY LICENSE 6 Edge and lane lines 27 Restrictions of the probationary license 7 White lane markings 27 The skills test 7 Crosswalks and stop lines 27 KEEPING THE DRIVER LICENSE 8 Yellow lane markings 27 Point system 8 Shared center lane 28 Habitual offender 9 OTHER LANE CONTROLS 29 Occupational license 9 Reversible lanes 29 Reinstating a revoked or suspended license 9 Reserved lanes 29 Driver license renewal 9 Flex Lane 30 Motor vehicle liability insurance METERED RAMPS 31 requirement 9 How to use a ramp meter 31 COVER i CONTENTS RULES FOR DRIVING SCHOOL BUSES 44 ROUNDABOUTS 32 General information for PARKING 45 all roundabouts 32 How to park on a hill -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page{s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.