Latin Parts of Speech in Historical and Typological Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCCASIONAL PAPER #12 SYNTACTICIZATION of TOPIC N JAPANESE and MANDARIN STUDENTS' LISH: a TEST of RUTHERFORD's MODEL Patricia

OCCASIONAL PAPER #12 1985 SYNTACTICIZATION OF TOPIC N JAPANESE AND MANDARIN STUDENTS' LISH: A TEST OF RUTHERFORD'S MODEL Patricia Ann Duff DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AS A SECOND WGUAGE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT WOA occAsIoNAL PAPER SERIES In recent years, a number of graduate students in the Department of English as a Second Language have selected the thesis option as part of their Master of Arts degree progran. Their research has covered a wide range of areas in second language learning and teaching. Many of these studies have attracted interest from others in the fieldr and in order to make these theses more widely availabler selected titles are now published in the Occasional Paper Series. This series, a supplement to the departmental publication Workinq Papersr may also include reports of research by members of the ESL faculty. Publication of the Occasional Paper Series is underwritten by a grant from the Ruth Crymes Scholarship Fund. A list of available titles and prices may be obtained from the department and is also included in each issue of Workinq Papers. The reports published in the Occasional Paper Series have the status of n*progressreports nn, and may be published elsewhere in revised form. Occasional Faper #12 is an HA thesis by Patricia Ann Duff. Her thesis comm~ttee-members were Craig Chaudron (chair), Jean Gibsonr and Richard Schmidt. This work should be cited as follows: DUFFr Patricia Ann. 1985. Syntacticization of Topic in Japanese and Mandarin Students1 English: A Test of RutherfordnsModel. Occasional Paper #12. Honolulu: Department of English as a Second Languager mversity of Hawaii at Manoa* Rutherford (1983) drafted a two-part model to account for the syntacticization of Topic in the English of Japanese and Mandarin learners. -

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

The Structures of Kora

2. CHAPTER 4 THE STRUCTURES OF KORA The contrastive sounds (phonemes) of any given language are combined to form the small units of meaning (morphemes) that are its building blocks, where some of these, such as nouns and verbs, are lexical, and others, such as markers of number, or tense and aspect, are grammatical. The morphology of Kora and the ways in which its morphemes are used in turn to compose phrases, full length clauses and longer stretches of connected discourse (or in other words, the syntax of the language) will be the focus of this chapter.1 The intention is to provide a short reference grammar for Kora, mainly to facilitate the study of the heritage texts in the original language, and chiefly with a non-specialist (though dedicated) reader in mind. For this reason, what the chapter offers is a primary description of the language, rather than a secondary linguistic modelling. (This is of course by no means to say that the description is ‘atheoretical’. It will quickly become apparent that there are several aspects of the language that are not easily explained, even in the most basic descriptive terms, without some degree of linguistic analysis.) While we have tried as far as possible to avoid terminology that is associated with any specific linguistic framework2 or else has become outdated jargon, it would have been difficult to proceed without drawing on at least some of the well-accepted and relatively transparent concepts that have come to form the received core of general linguistic description. The meanings of any mildly technical terms introduced in the course of the chapter will, it is hoped, become clear from the context. -

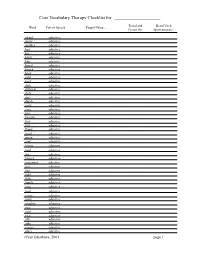

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Linguistics, Program of 1981 Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ling_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Publication Info Published in Folia Linguistica Historica, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1981, pages 3-34. Disterheft, D. (1981). Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive. Folia Linguistica Historica, 2(1), 3-34. DOI: 10.1515/ flih.1981.2.1.3 © 1981 Societas Linguistica Europaea. This Article is brought to you by the Linguistics, Program of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foli.lAfl//ui.tfcoFolia Linguistica HfltorlcGHistorica II/III/l 'P'P.pp. 8-U3—Z4 © 800£etruSocietae lAngu,.ticaLinguistica Etlropaea.Evropaea, 1981lt)8l REMARKSBEMARKS ONON THETHE HISTORYHISTOKY OFOF THETHE INDO-EUROPEANINDO-EUROPEAN INFINITIVEINFINITIVE i DOROTHYDOROTHY DISTERHEFTDISTERHEFT I 1.1. INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION WithWith thethe exceptfonexception ofof Indo-IranianIndo-Iranian (Ur)(Hr) andand CelticCeltic allall historicalhistorical Indo-EuropeanIndo-European (IE)(IE) subgroupssubgroups havehave a morphologicalIymorphologically distinctdistinct II infinitive.Infinitive. However,However, nono singlesingle proto-formproto-form cancan bebe reconstructedreconstructed -

Navajo Verb Stem Position and the Bipartite Structure of the Navajo

678 REMARKSANDREPLIES NavajoVerb Stem Positionand the BipartiteStructure of the NavajoConjunct Sector Ken Hale TheNavajo verb stem appears at the rightmost edge of the verb word. Innumerouscases it forms a lexicalconstituent with a preverb,occur- ringat theleftmost edge of thesurface verb word, much in themanner ofDutchand German verb-particle arrangements in verb-secondfinite clauses.In Navajothe initial and finalpositions are separated by eight morphemeorder ‘ ‘slots’’ recognizedin the Athabaskan literature (and describedin detail for Navajo in Young and Morgan 1987). A phono- logicalsolution to this and a numberof otherdeep-surface disparities isexploredhere, based on theinsights of earlierworks on theNavajo verb,including Speas 1984, 1990, McDonough 1996, 2000, and Rice 1989, 2000. Keywords: verbmorphology, morphosyntactic disparity, spell-out, Navajo,Athabaskan 1Verb Stem Position TheNavajo verb stem forms asinglelexical constituent with the prefixal, particle-like category called preverb inthe Athabaskan linguistic literature (see Rice2000). However, like particle- verbcombinations in Dutchand German verb-second clauses, the parts of thisconstituent in the Navajocounterpart are separated in the surface forms ofverbal projections in syntax. In the Navajoversion of thisarrangement, the preverb occupies the leftmost position in the verb word, andthe verb stem occupies the rightmost position. TheNavajo verb in (1) canbe used to illustrate the phenomenon. The verb is segmented intoits various parts in (2), and the components are identified in slightly greater detail in (3). (1) Sila´o t’o´o´’go´o´ ch’´õ shidinõ´daøzh.(Young and Morgan 1987:283) ‘Thepoliceman jerked me outdoors (to get me out of afight).’ (2) ch’´õ sh d n-´ daøzh PreverbObject Qualifier Mode/ SubjVoice V (stem) Iwishto dedicate thisarticle totheNavajo Language Academy, asmall groupof linguists and teachers devotedto Navajolanguage research andeducation. -

The Compound Noun in Northern Sotho

THE COMPOUND NOUN IN NORTHERN SOTHO BY LEKAU ELEAZAR MPHASHA Dissertation presented for the Degree of Doctor of Literature at the University of Stellenbosch. PROMOTOR: PROF. M. V. VISSER DECEMBER 2006 http://scholar.sun.ac.za i DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. -------------------------------- ---------------------------- Signature Date http://scholar.sun.ac.za ii ABSTRACT This study explores the various elements which appear in compound nouns in Northern Sotho. The purpose of this study fill in an important gap in the Northern Sotho language studies as regards the morphological structure of compound nouns in Northern Sotho. This study is organized as follows: CHAPTER ONE presents an introduction to the study. The introductory sections which appear in this chapter include the aim of the study, the methodology and different views of researchers of other languages on compound nouns. Different categories which appear with the noun in the Northern Sotho compound are identified. CHAPTER TWO deals with the different features of the noun in Northern Sotho. It examines the various class prefixes, nominal stems/roots and nominal suffixes which form nouns. Nouns appear in classes according to the form of their prefixes. The morphological structures of the nouns have been presented. It also reviews the meanings, sound/phonological changes and origins of nouns. CHAPTER THREE is concerned with the nominal heads of compound nouns. It examines compounds that are formed through a combination of nouns, and compounds that are formed from nouns together with other syntactic categories. -

Unity and Diversity in Grammaticalization Scenarios

Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 16 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. ISSN: 2363-5568 Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language science press Walter Bisang & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). 2017. Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios (Studies in Diversity Linguistics -

Grammatical Sketch of Beng

Mandenkan Numéro 51 Bulletin d’études linguistiques mandé Printemps 2014 ISSN: 0752-5443 Grammatical sketch of Beng Denis PAPERNO University of Trento, Italy [email protected] Denis Paperno Content 1. Introduction 1 2. General information 9 2.1. Beng people and their language 9 2.2. Sociolinguistic situation 11 2.3. Names of the language 12 3. The history of Beng studies 12 3.1. Students of the Beng language and society 12 3.2. Beng dialects according to reports from the early 1900s 13 3.2.1. Delafosse: Beng of Kamélinsou 15 3.2.3. Tauxier: Beng of Groumania neighbourhood 16 4. Beng phonology 18 4.1. Phonological inventory 18 4.1.1. Tones 20 4.1.2. Syllable structure 22 4.1.3. Segmental sandhi 22 4.1.4. Tonal sandhi 22 4.2. Morphonology 23 4.2.1. ŋC simplification 23 4.2.2. Deletion of /l/ 24 4.2.3. High tone in the low tone form of verbs 24 5. Personal Pronoun Morphology 25 5.1. On the allomorphy of the 1SG subject pronoun 27 5.2. Contraction with 3SG object pronoun 28 5.3. Subject series of pronouns 29 5.4. Stative pronouns with verbs tá, nṵ̄ 29 6. Morphology of content words 30 6.1. Tonal changes in suffixation 31 6.1.1. Mobile tone suffixes 31 6.1.2. Low tone suffixes 31 6.1.3. Other suffixes 31 6.1.4. Stems ending in L tone 31 3 Denis Paperno 6.1.5. The verb blö ‘to press out’ 32 6.2. -

Overt Pronouon Constraint Effects in Second Lanugage Japanese

Overt Pronoun Constraint effects in second language Japanese Tokiko Okuma Department of Linguistics McGill University Montreal, Quebec April 2, 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY © Copyright by Tokiko Okuma 2014 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the applicability of the Full Transfer/Full Access hypothesis (FT/FA) (Schwartz & Sprouse, 1994, 1996) by investigating the interpretation of the Japanese pronoun (kare ‘he’) by adult English and Spanish speaking learners of Japanese. The Japanese, Spanish, and English languages differ with respect to interpretive properties of pronouns. In Japanese and Spanish, overt pronouns disallow a bound variable interpretation in subject and object positions. By contrast, In English, overt pronouns may have a bound variable interpretation in these positions. This is called the Overt Pronoun Constraint (OPC) (Montalbetti, 1984). The FT/FA model suggests that the initial state of L2 grammar is the end state of L1 grammar and that the restructuring of L2 grammar occurs with L2 input. This hypothesis predicts that L1 English speakers of L2 Japanese would initially allow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions, transferring from their L1s. Nevertheless, they will successfully come to disallow a bound variable interpretation as their proficiency improves. In contrast, L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese would correctly disallow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions from the beginning. In order to test these predictions, L1 English and L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese at intermediate and advanced levels of proficiency were compared with native Japanese speakers in their interpretations of pronouns with quantified i antecedents in two tasks. -

The Locative Preposition in Xitsonga Masonto Rivalani

THE LOCATIVE PREPOSITION IN XITSONGA by MASONTO RIVALANI XENON A research report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF ARTS in TRANSLATION STUDIES AND LINGUISTICS in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES (School of Languages and Communication Studies) at the UNIVERSITY OF LIMPOPO SUPERVISOR: PROF SJ KUBAYI 2019 DECLARATION I, Rivalani Xenon Masonto, declare that this research report entitled “THE LOCATIVE PREPOSITION IN XITSONGA” is my own work and that all the sources that I have used have been acknowledged by means of complete references. ………………………………… …………………………. R.X. Masonto (Ms.) Date DEDICATION To my younger self, I am proud you never gave up. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Prof S.J Kubayi, thank you for your support, kindness, guidance and your fatherly love. It is not every day where a student gets to be supervised by a Great Master like you. There is not even a single day where I felt lost in this study because you were always there. It is indeed true that “mutswari a hi wa wun’we”, thank you very much. May the Good Lord bless you. Secondly, I would also like to express my sincere appreciation to my mom, Rhungulani Mavis Mkhabele for her unwavering support and love. Himpela “ku veleka i vukosi”. Rirhandzu ra n’wina hi rona ri nga ndzi kotisa. Thirdly, I would like to thank my father, David Masonto, my little people, Bornwise, Best, Kalush and Benjamin for the smiles that gave me hope to never give up. Last but not least, I thank God for giving me the strength, mercy, wisdom and courage to continue with my studies even at a time of despair. -

The Structured Compact Tag-Set for Luganda

International Journal on Natural Language Computing (IJNLC) Vol. 5, No.4, August 2016 THE STRUCTURED COMPACT TAG -SET FOR LUGANDA Robert Ssali Balagadde 1 and Parvataneni Premchand 2 1, 2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University College of Engineering, Osmania University, Hyderabad, India ABSTRACT A tag-set for tagging Luganda words has been in absence for quite a long time leading to absence of Luganda Language resources used in Computational Linguistic (CL) and Natural Language Processing (NLP). As a result, this research paper proposes and presents a Structured Compact Tag-set for Luganda (SCTL) in a bid to address this gap, and emphasis has been directed towards presenting the structures. SCTL incorporates a number of new concepts aimed at reducing redundancy in an annotated corpus. In line with this, Tag Length Minimization Strategies (TLMS) have been proposed and implemented in SCTL. The morpho-syntactic properties captured in SCTL were identified through conducting a morphological analysis and word categorization along the various parts of speeches (POS) of Luganda. To demonstrate the suitability of SCTL to tag Luganda text, a sample text extracted from Bukedde, an online Luganda news paper, has been tagged and presented; however, identification and validation of the various tags of SCTL is proposed as a component of continuity of this research work. This paper demonstrates how Concord Number (CN) captured in SCTL can be used to check conventional agreement between words. Storage Efficiencies, namely, ηt (individual) and ηat (batch) are novel metrics proposed in this research work, which can be used in evaluating how a particular tag-set is performing in terms of efficient storage usage at tag level and corpus (or batch) level respectively.