The Preverb Eis- and Koine Greek Aktionsart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

Show Business: Deixis in Fifth-Century Athenian Drama

Show Business: Deixis in Fifth-Century Athenian Drama by David Julius Jacobson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Donald Mastronarde Professor Leslie Kurke Professor Mary-Kay Gamel Professor Shannon Jackson Spring 2011 Show Business: Deixis in Fifth-Century Athenian Drama Copyright 2011 by David Julius Jacobson Abstract Show Business: Deixis in Fifth-Century Athenian Drama by David Julius Jacobson Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair In my dissertation I examine the use of deixis in fifth-century Athenian drama to show how a playwright’s lexical choices shape an audience’s engagement with and investment in a dramatic work. The study combines modern performance theories concerning the relationship between actor and audience with a detailed examination of the demonstratives ὅδε and οὗτος in a representative sample of tragedy (and satyr play) and in the full Aristophanic corpus, and reaches conclusions that aid and expand our understanding of both tragedy and comedy. In addition to exploring and interpreting a number of particular scenes for their inter-actor dynamics and staging, I argue overall that tragedy’s predilection for ὅδε , a word which by definition conveys a strong spatio- temporal presence (“this <one> here / now”), pointedly draws the spectators into the dramatic fiction. The comic poet’s preference for οὗτος (“that <one> just mentioned” / “that <one> there”), on the other hand, coupled with his tendency to directly acknowledge the audience individually and in the aggregate, disengages the spectators from the immediacy of the tragic tetralogies and reengages them with the normal, everyday world to which they will return at the close of the festival. -

Deixis in the Song Lyrics of One Direction

AICLL Annual International Conference on Language and Literature (AICLL) Volume 2021 Conference Paper Deixis in the Song Lyrics of One Direction Savitri Rahmadany and Rahmad Husein Universitas Negeri Medan, Medan, Indonesia ORCID: Savitri Rahmadany: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2729-2969 Abstract This study aimed to investigate the types of deixis used in the song lyrics of One Direction, to find out the dominant types used and to describe the semantic meaning of the deixis. The song lyrics are associated with deixis since they express the singer’s or song writer’s feelings or emotions represented by some expressions of human thoughts, ideas and opinions. This study was conducted using a descriptive qualitative research design. The data were obtained from five songs of One Direction entitled Up All Night, Change My Mind, Everything about You, Little Things, and Right Now. Three types of deixis were found in the five songs and there were 108 deixis found in the lyrics. Person deixis was investigated as the most dominant type used Corresponding Author: in the lyrics. All deixis had their semantic meanings based on the situations of the songs. Savitri Rahmadany [email protected] Keywords: Deixis, Song, Lyrics, Semantics. Published: 11 March 2021 Publishing services provided by Knowledge E Savitri Rahmadany and Rahmad Husein. This article is 1. Introduction distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Along with the development of the era of music in society music has been transformed Attribution License, which into a commercial entertainment or economic goods. Music is a social or cultural tool permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the that contains thoughts, ideas, opinions, of human beings, as outlined in the forms of original author and source are song lyrics. -

DEIXIS and SPATIAL ORIENTATION in ROUTE DIRECTIONS Wolfgang

DEIXIS AND SPATIAL ORIENTATION IN ROUTE DIRECTIONS Wolfgang Klein Max-Planck-Institut für Psycholinguistik Nijmegen, Netherlands Allwo dort die schönen Trompeten blasen, Da ist mein Haus, mein Haus von grünem Rasen. INTRODUCTION All natural languages allow reference to places, ex pression of spatial relations and localization of objects and events. The specific devices which they have developed to that purpose vary considerably. This may also be true for the underlying concept of space (Malotki, 1979), but there are some general features, as well. Two of them are particularly relevant to the question of how human exper ience is reflected in language structure. First, place ref erence, or local reference, is typically not obligatory. Its expression or lack thereof is left up to the speaker. Temporal reference, on the other hand, is very often obli gatory. It is a built-in feature of many languages. With a a few exceptions, utterances in these languages will be "tensed." Second, all languages exhibit two strategies of local (and often other) reference, one of them rooted in the actual speech situation (deictic reference) and the other one not. I have nothing to say here about the asymmetry between temporal and local reference, except that it is a mystery and casts some doubt on the truism that time and space are equally fundamental categories of human experience : at least, the marks they have left in the structure of very many languages, including the familiar Indoeuropean 283 languages, are not equally deep.1 The difference between deictic and non-deictic reference is best exemplified by two series of expressions. -

A Study of Deixis in Relation to Lyric Poetry by Keith Michael Charles Green

A Study of Deixis in Relation To Lyric Poetry by Keith Michael Charles Green Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. in the Department of English Language I , University of Sheffield October 1992 A STUDY OF DEIXIS IN RELATION TO LYRIC POETRY KEITH MICHAEL CHARLES GREEN SUMMARY This thesis is an examination of the role of deixis in a specific literary genre, the lyric poem. Deixis is seen as not only a fundamental aspect of human discourse, but the prime function in the construction of 'world-view' and the expression of subjective reference. In the first part of the thesis current problems in deictic theory are explored and the relationship between deixis and context is clarified. A methodology for the analysis of deixis in any given text is constructed and the pragmatics of the lyric poem described. The methodology is applied to detailed analyses of selected lyric poems of Vaughan, Wordsworth, Pound and Ashberry. There is a demonstration of how deixis contributes to the functioning of the poetic persona, and the changes in deixis occurring diachronically in the poetry are examined. In conclusion it is demonstrated that although deixis necessarily reflects the changing subjectivity of the poetic persona through time, there are many elements of deixis which are constant across historical and stylistic boundaries. There remains a tension between the constraints of the genre, the necessary functions of deixis and the shifting subjectivities which that deixis reflects. CONTENTS Page Chapter One: Deixis, Contexts and Literature 1 1. What is deixis? 1 2. The traditional categories 14 2.1 Time deixis 15 2.2 Place deixis 19 2.3 Person deixis 23 2.4 Social deixis 24 2.5 Discourse deixis 25 3. -

The Linguistic Categorization of Deictic Direction in Chinese – with Reference to Japanese – Christine Lamarre

The linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Chinese – With reference to Japanese – Christine Lamarre To cite this version: Christine Lamarre. The linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Chinese – With reference to Japanese –. Dan XU. Space in Languages of China, Springer, pp.69-97, 2008, 978-1-4020-8320-4. hal-01382316 HAL Id: hal-01382316 https://hal-inalco.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01382316 Submitted on 16 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Lamarre, Christine. 2008. The linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Chinese — With reference to Japanese. In Dan XU (ed.) Space in languages of China: Cross-linguistic, synchronic and diachronic perspectives. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York: Springer, pp.69-97. THE LINGUISTIC CATEGORIZATION OF DEICTIC DIRECTION IN CHINESE —— WITH REFERENCE TO JAPANESE —— Christine Lamarre, University of Tokyo Abstract This paper discusses the linguistic categorization of deictic direction in Mandarin Chinese, with reference to Japanese. It focuses on the following question: to what extent should the prevalent bimorphemic (nondeictic + deictic) structure of Chinese directionals be linked to its typological features as a satellite-framed language? We know from other satellite-framed languages such as English, Hungarian, and Russian that this feature is not necessarily directly connected to satellite-framed patterns. -

An Introduction, Phonological, Morphological, Syntactic to The

AN INTRODUCTION, PHONOLOGICAL, MORPHOLOGICAL, SYNTACTIC, TO THE GOTHIC OF ULFILAS. BY T. LE MARCHANT DOUSE. LONDON: TAYLOR AND FRANCIS, RED LION COURT, FLEET STREET. 1886, PRINTED BY TAYLOR AND FRANCIS, BED LION COURT, FLEET STREET. PREFACE. THIS book was originally designed to accompany an edition of Ulfilas for which I was collecting materials some eight or nine years ago, but which various con- siderations led me to lay aside. As, however, it had long seemed to me equally strange and deplorable that not a single work adapted to aid a student in acquiring a knowledge of Gothic was to be found in the English book-market, I pro- ceeded to give most of the time at my disposal to the " building up of this Introduction," on a somewhat larger scale than was at first intended, in the hope of being able to promote the study of a dialect which, apart from its native force and beauty, has special claims on the attention of more than one important class of students. By the student of linguistic science, indeed, these claims are at once admitted ; for the Gothic is one of the pillars on which rests the comparative grammar of the older both Indo-European languages in general, and also, pre-eminently, of the Teutonic cluster of dialects in particular. a But good knowledge of Gothic is scarcely less valuable to the student of the English language, at rate, of the Ancient or any English Anglo-Saxon ; upon the phonology of which, and indeed the whole grammar, the Gothic sheds a flood of light that is not to be got from any other source. -

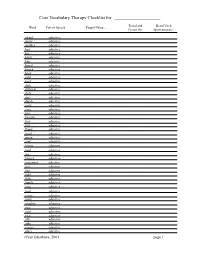

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Linguistics, Program of 1981 Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ling_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Publication Info Published in Folia Linguistica Historica, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1981, pages 3-34. Disterheft, D. (1981). Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive. Folia Linguistica Historica, 2(1), 3-34. DOI: 10.1515/ flih.1981.2.1.3 © 1981 Societas Linguistica Europaea. This Article is brought to you by the Linguistics, Program of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foli.lAfl//ui.tfcoFolia Linguistica HfltorlcGHistorica II/III/l 'P'P.pp. 8-U3—Z4 © 800£etruSocietae lAngu,.ticaLinguistica Etlropaea.Evropaea, 1981lt)8l REMARKSBEMARKS ONON THETHE HISTORYHISTOKY OFOF THETHE INDO-EUROPEANINDO-EUROPEAN INFINITIVEINFINITIVE i DOROTHYDOROTHY DISTERHEFTDISTERHEFT I 1.1. INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION WithWith thethe exceptfonexception ofof Indo-IranianIndo-Iranian (Ur)(Hr) andand CelticCeltic allall historicalhistorical Indo-EuropeanIndo-European (IE)(IE) subgroupssubgroups havehave a morphologicalIymorphologically distinctdistinct II infinitive.Infinitive. However,However, nono singlesingle proto-formproto-form cancan bebe reconstructedreconstructed -

Advanced Greek Grammar Course Syllabus

Front Range Bible Institute Syllabus for NTL701 Advanced Greek Grammar (Spring 2018) Professor Timothy L. Dane I. Course Description This course is an advanced study in Greek grammar. It is designed to help New Testament language students expand and develop their ability to do exegesis from the Greek New Testament. Students must have completed at least two years of Greek studies before taking this course (first year Greek and Greek exegesis). The primary structure of the class will revolve around classroom interaction that is driven from outside studies of the students. The students will prepare for each class by reading on the assigned discussion topics and coming to class prepared for discussion. Each week a different student will prepare an outline of that topic and will act as moderator for the discussions that week. Students should try to identify the most significant points, questions or issues as they prepare. This will enable them to engage readily in any discussion which takes place and it should give them a good start in making notes and summaries which will eventually be turned in for evaluation. Student presentations will summarize for the whole class the major points to be noted, questions that are raised and especially the significance for understanding of the text of the New Testament. II. Course Objectives A. To develop a greater skill in interpreting the Greek New Testament B. To help ground the students in every facet of Koine Greek grammar C. To help students avoid common grammatical errors in using the Greek language D. To help the students function more independently as exegetes as they evaluate the various exegetical sources and materials they use in exegesis E. -

Navajo Verb Stem Position and the Bipartite Structure of the Navajo

678 REMARKSANDREPLIES NavajoVerb Stem Positionand the BipartiteStructure of the NavajoConjunct Sector Ken Hale TheNavajo verb stem appears at the rightmost edge of the verb word. Innumerouscases it forms a lexicalconstituent with a preverb,occur- ringat theleftmost edge of thesurface verb word, much in themanner ofDutchand German verb-particle arrangements in verb-secondfinite clauses.In Navajothe initial and finalpositions are separated by eight morphemeorder ‘ ‘slots’’ recognizedin the Athabaskan literature (and describedin detail for Navajo in Young and Morgan 1987). A phono- logicalsolution to this and a numberof otherdeep-surface disparities isexploredhere, based on theinsights of earlierworks on theNavajo verb,including Speas 1984, 1990, McDonough 1996, 2000, and Rice 1989, 2000. Keywords: verbmorphology, morphosyntactic disparity, spell-out, Navajo,Athabaskan 1Verb Stem Position TheNavajo verb stem forms asinglelexical constituent with the prefixal, particle-like category called preverb inthe Athabaskan linguistic literature (see Rice2000). However, like particle- verbcombinations in Dutchand German verb-second clauses, the parts of thisconstituent in the Navajocounterpart are separated in the surface forms ofverbal projections in syntax. In the Navajoversion of thisarrangement, the preverb occupies the leftmost position in the verb word, andthe verb stem occupies the rightmost position. TheNavajo verb in (1) canbe used to illustrate the phenomenon. The verb is segmented intoits various parts in (2), and the components are identified in slightly greater detail in (3). (1) Sila´o t’o´o´’go´o´ ch’´õ shidinõ´daøzh.(Young and Morgan 1987:283) ‘Thepoliceman jerked me outdoors (to get me out of afight).’ (2) ch’´õ sh d n-´ daøzh PreverbObject Qualifier Mode/ SubjVoice V (stem) Iwishto dedicate thisarticle totheNavajo Language Academy, asmall groupof linguists and teachers devotedto Navajolanguage research andeducation. -

Unity and Diversity in Grammaticalization Scenarios

Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 16 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. ISSN: 2363-5568 Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language science press Walter Bisang & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). 2017. Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios (Studies in Diversity Linguistics