Of Holy Communion/ Eucharist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Offertory Our Firstfruits the Offertory

God. For in a sense when we offer our gifts at the Altar, we are actually offering ourselves. Our money is a part of ourselves, what we have earned, what we have la- bored for. And thus the offering of our possessions be- comes the offering of our very beings. But if we think of our offering in the Service as a sacrifice of ourselves, then we will also want to carry out this sacrifice in our daily lives—otherwise the offering of our possessions would be only hypocrisy. Furthermore, when we offer at the Altar, we are offer- ing in union with our Lord Jesus Christ—offering our imperfect sacrifices in union with the perfect Sacrifice of His Body and Blood, which He offered to His heavenly Father. For it is only because of His perfect Sacrifice that our sacrifices are of any value. The Offertory Our Firstfruits The Offertory Finally, our offering is to be the firstfruits of our la- bor—not what happens to be left over after all of our bills and debts have been paid. But our offering at the Altar ought to be a sacrifice of the first and the best we can give. If we Christians would consider our offerings in this way—as a fulfillment of our Royal Priesthood, a privi- lege, and a sacrifice of our firstfruits, then we would more readily offer ourselves, our bodies, and souls and I N C A R N A T E W O R D T R A C T S E R I E S all things as a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable to God - 2 4 - through Jesus Christ our Lord. -

The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F

Valparaiso University ValpoScholar Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers Institute of Liturgical Studies 2017 The weT ntieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Liturgy and Worship Commons Recommended Citation Baldovin, John F. S.J., "The wT entieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects" (2017). Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers. 126. http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers/126 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Liturgical Studies at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin, S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry Introduction Metanoiete. From the very first word of Jesus recorded in the Gospel of Mark reform and renewal have been an essential feature of Christian life and thought – just as they were critical to the message of the prophets of ancient Israel. The preaching of the Gospel presumes at least some openness to change, to acting differently and to thinking about things differently. This process has been repeated over and over again over the centuries. This insight forms the backbone of Gerhard Ladner’s classic work The Idea of Reform, where renovatio and reformatio are constants throughout Christian history.1 All of the great reform movements in the past twenty centuries have been in response to both changing cultural and societal circumstances (like the adaptation of Christianity north of the Alps) and the failure of Christians individually and communally to live up to the demands of the Gospel. -

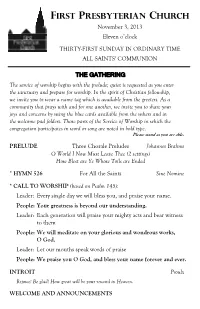

Ordinary 31C 11-3-2013 C&B.Pub

FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH November 3, 2013 Eleven o’clock THIRTY-FIRST SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME ALL SAINTS' COMMUNION THE GATHERING The service of worship begins with the prelude; quiet is requested as you enter the sanctuary and prepare for worship. In the spirit of Christian fellowship, we invite you to wear a name tag which is available from the greeters. As a community that prays with and for one another, we invite you to share your joys and concerns by using the blue cards available from the ushers and in the welcome pad folders. Those parts of the Service of Worship in which the congregation participates in word or song are noted in bold type. Please stand as you are able. PRELUDE Three Chorale Preludes Johannes Brahms O World I Now Must Leave Thee (2 settings) How Blest are Ye Whose Toils are Ended * HYMN 526 For All the Saints Sine Nomine * CALL TO WORSHIP (based on Psalm 145): Leader: Every single day we will bless you, and praise your name. People: Your greatness is beyond our understanding. Leader: Each generation will praise your mighty acts and bear witness to them People: We will meditate on your glorious and wondrous works, O God. Leader: Let our mouths speak words of praise People: We praise you O God, and bless your name forever and ever. INTROIT Proulx Rejoice! Be glad! How great will be your reward in Heaven. WELCOME AND ANNOUNCEMENTS CALL TO CONFESSION PRAYER OF CONFESSION Almighty God, we confess that we are unable to disentangle the good from the bad within us. -

“Paul, a Plan, & an Epistle”

Weekly Events THE LORD’S DAY Middle School youth group, Mon @6:30pm JANUARY 24, 2021 Boy Scouts, Tues @7pm Kids4Christ, Tuesday @4:30pm HS Youth Group, Weds @ 6:30pm Women’s Wednesday bible studies @9:30am Men’s Bible Study group, Thurs @6:30am Girls Basketball, Fri @ 5pm AA Meeting, Sat @7:30pm Youth Winter Calendar: Please watch this space, and our website calendar, for information on upcoming events. Possible winter retreat or day event in February being planned. • Middle school and High school youth group is up and running on Mondays and Wednesdays, with a HS bible study on Sunday evenings. Times and info can be found on our website. • We have 2 winter retreats being planned as follows: HS Ski trip on February 19-21 (location TBD) and the annual MS trip to Roundtop, March 5-6. More details will be sent out via e-letter as well as during the youth group so please stay tuned. Our Sunday school adult classes are back this Sunday. We have a ladies class led by Sandy Currin from a book called, “Life Giving Leaders”, and Dan Zagone A is leading a class on sermon discussion each week. So grab a coffee, and stay for “Paul, Plan, some good discussion after the service. Winter weather reminder: In the event that we do have snow or icy conditions this winter, and decide to cancel worship, cancellation information will be sent out an via email the morning of, and can also be found on our website, and our church & Epistle” answering machine. -

SAINT BASIL the GREAT ALTAR SERVER MANUAL Prayers of An

SAINT BASIL THE GREAT ALTAR SERVER MANUAL Prayers of an Altar Server O God, You have graciously called me to serve You upon Your altar. Grant me the graces that I need to serve You faithfully and wholeheartedly. Grant too that while serving You, may I follow the example of St. Tarcisius, who died protecting the Eucharist, and walk the same path that led him to Heaven. St. Tarcisius, pray for me and for all servers. ALTAR SERVER'S PRAYER Loving Father, Creator of the universe, You call Your people to worship, to be with You and each other at Mass. Help me, for You have called me also. Keep me prayerful and alert. Help me to help others in prayer. Thank you for the trust You've placed in me. Keep me true to that trust. I make my prayer in Jesus' name, who is with us in the Holy Spirit. Amen. 1 PLEASE SIGN AND RETURN THIS TOP SHEET IMMEDIATELY To the Parent/ Guardian of ______________________________(server): Thank you for supporting your child in volunteering for this very important job as an Altar Server. Being an Altar Server is a great honor – and a responsibility. Servers are responsible for: a) knowing when they are scheduled to serve, and b) finding their own coverage if they cannot attend. (email can help) The schedule is emailed out, prior to when it begins. The schedule is available on the Church website, and published the week before in the Church Bulletin. We have attached the, “St. Basil Altar Server Manual.” After your child attends the two server training sessions, he/she will most likely still feel unsure about the job – that’s OK. -

Reverenómo Er Mar Angeica

Mass of Christian Burial A n d Rite of Committal ReverenÓMoer MarAngeica of the Annunciation, P. C. P. A . Abbess Emerita, Our Lady of the Angels Monastery FRidAy, APRiL 1, 2016 Moer MarAngeica April 20, 1923 – March 27, 2016 Professed January 2, 1947 Mass of Christian Burial a n d Rite of Committal Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament Hanceville, Alabama Table of Contents I. Requiem Mass 3 The Guidelines for Reception of Holy Communion can be found on the inside back cover of this booklet. II. Solemn Procession and Rite of Committal 15 Introductory Rites Processional Requiem aeternam CHOIR Giovanni Martini (1706-1784); arr. Rev. Scott A. Haynes, S.J.C. Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) from Requiem ANT: Requiem aeternam dona ei ANT: Rest eternal grant unto her, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat ei. O Lord, and may light perpetual shine upon her. PS 130: De profundis clamavit ad te PS 130: Out of the depths I have cried to Domine… thee, O Lord... (CanticaNOVA, pub.) Kyrie Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison. R. Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Collect P. We humbly beseech your mercy, O Lord, for your servant Mother Mary Angelica, that, having worked tirelessly for the spread of the Gospel, she may merit to enter into the rewards of the Kingdom. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. R. Amen. 3 The Liturgy of the Word First Reading Book of Wisdom 3:1-9 He accepted them as a holocaust. -

Quality Silversmiths Since 1939. SPAIN

Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com - ARTIMETAL - PROCESSIONALIA 2014-2015 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN ARTISTIC SILVER INDEXINDEX Presentation ......................................................................................... Pag. 1-12 ARTISTIC SILVER - ARTIMETAL ARTISTICPresentation SILVER & ARTIMETAL Pag. 1-12 ChalicesChalices && CiboriaCiboria ........................................................................... Pag. 13-6713-52 MonstrancesCruet Sets & Ostensoria ...................................................... Pag. 68-7853 TabernaclesJug & Basin,........................................................................................... Buckets Pag. 79-9654 AltarMonstrances accessories & Ostensoria Pag. 55-63 &Professional Bishop’s appointments Crosses ......................................................... Pag. 97-12264 Tabernacles Pag. 65-80 PROCESIONALIAAltar accessories ............................................................................. Pag. 123-128 & Bishop’s appointments Pag. 81-99 General Information ...................................................................... Pag. 129-132 ARTIMETAL Chalices & Ciboria Pag. 101-115 Monstrances Pag. 116-117 Tabernacles Pag. 118-119 Altar accessories Pag. 120-124 PROCESIONALIA Pag. 125-130 General Information Pag. 131-134 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. Justo Dorado, 12 28040 Madrid, Spain Product design: Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. CHALICES & CIBORIA Our silversmiths combine -

St. Jude's Anglican Church Plaque Inventory Report

St. Jude’s Anglican Church Plaque Inventory Report Prepared by Brantford Heritage Committee Places of Worship Sub-Committee February 2019 Brantford Heritage Committee Places of Worship Sub-Committee St. Jude’s Anglican Church Plaque Inventory Executive Summary In November of 2018, the Places of Worship Sub-Committee of the Brantford Heritage Committee completed an inventory of the memorial plaques located in the interior of the former St. Jude’s Anglican Church. As the building had recently been sold for adaptive re-use as a condominium, there had been a request from the new owners of St. Jude’s Anglican Church, Andrew Neill Construction Inc. (ANC), to the Brantford Heritage Committee to provide direction as to how best conserve these historic features and elements of the church with heritage value. The plaque inventory comprised a form recording the location, size, material and date of each plaque. The transcriptions of each plaque were documented, and all were photographed. A total of 25 plaques and one commendation were recorded. The majority of the plaques were small engraved brass plates acknowledging the contributions of parish members towards the acquisition of elements of the church and towards the maintenance and restoration of the murals, organ and stain glass windows. A smaller number of plaques were primarily memorial records dedicated to members of the parish and comprising larger marble and cast bronze plaques. Three plaques, however, were deemed to have a broader community significance, with one recognizing Colonel Jasper Tough Gilkison (an early political figure in the Brantford community), and two plaques listing 37 citizens of Brantford who had lost their lives during World Wars I and II. -

Rodman Elected Bishop 'Two Architectural Gems'

Volume 45, Number 3. News for the Parish of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church March 2017 Rodman Elected Bishop ‘Two architectural gems’ On Saturday, March 4, the Rev. by the Rev. D. Dixon Kinser, Rector Samuel Rodman was elected XII Bishop Diocesan of the Not long ago, a thick manila Diocese of North Carolina at envelope arrived in my a Special Electing Convention mailbox. Inside was a letter at Canterbury School in from Ed Bouldin, a parishioner Greensboro. St. Paul’s clergy and architect. Ed wrote, attending the convention were “Dear Dixon, 875 West Fifth the Rev. D. Dixon Kinser, the is a mid-century modern Rev. Sara C. Ardrey-Graves, jewel. St. Paul’s now has the Rev. John E. Shields and two architectural gems—St. the Rev. Lauren A. Villemuer- and laity, in collaborative Paul’s designed by Ralph I admit, 875 West Fifth’s Drenth. St. Paul’s lay delegates local and global mission Adams Cram and 875 West primary initial appeal for were Charles Corpening, Bill through the Together Now Fifth designed by George me was the proximity to Goodson, Courtney Kluttz, campaign, helping to raise $20 Matsumoto.” the church and the size and Ruth Prongay, David Tamer million. Prior to that, Rodman flexibility of the space inside. and Bill Wells. spent 16 years as the Rector Ed enclosed a 69-page print- Someone described it as “a of St. Michael’s in Milton, out from the North Carolina classic mid-century box,” and “I am deeply honored and Massachusetts. Modernist Houses web site, I agreed, thinking it is rather grateful and, with God’s help, where Matsumoto is honored boxy. -

Eucharistic Practice & Sacramental Theology in Pandemic Times

The essential nature of the Eucharist and the modes of its reception DAVID N. BELL & JOHN COURAGE ON BEHALF OF QUEEN’S COLLEGE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY he Faculty of Theology at Queen’s College held two well-attended T consultative sessions by means of GoToMeeting on June 15 and June 22, 2020. The discussions were lively and informative, and alt- hough a great deal of ground was covered, there were three questions of major concern. All three pertain directly to the nature and reception of the Eucharist during the present pandemic. First, how inclusive should the Eucharist be? Or, putting it another way, who constitutes the Body of Christ at the Lord’s Table? Secondly, since the physical reception of the Eucharist – the bread and the wine – is precluded at the present time, in what way or ways can we understand its spiritual reception? And thirdly, can the Eucharist act in a similar way to an icon, namely, as a window connecting this world with the transfigured cosmos? The overwhelming opinion of those present at both sessions was that the Eucharist, which is a multi-faceted celebration, should be as inclusive as possible, and that – once the physical reception is again made possible – no one who presents themselves at the altar should be refused. It is not the business of any member of the clergy to try to channel God’s grace and, as a consequence, anyone who wishes to receive communion should do so – what happens after that is entirely up to God. All those, therefore, who par- ticipate in any form of online worship may be regarded as belonging to the Body of Christ, and we must remember that Christ himself said that he had many sheep which were not of this fold (Jn 10:16). -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People