Narrative of the Institution by Roddy Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divine Liturgy

THE DIVINE LITURGY OF OUR FATHER AMONG THE SAINTS JOHN CHRYSOSTOM H QEIA LEITOURGIA TOU EN AGIOIS PATROS HMWN IWANNOU TOU CRUSOSTOMOU St Andrew’s Orthodox Press SYDNEY 2005 First published 1996 by Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia 242 Cleveland Street Redfern NSW 2016 Australia Reprinted with revisions and additions 1999 Reprinted with further revisions and additions 2005 Reprinted 2011 Copyright © 1996 Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission from the publisher. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data The divine liturgy of our father among the saints John Chrysostom = I theia leitourgia tou en agiois patros imon Ioannou tou Chrysostomou. ISBN 0 646 44791 2. 1. Orthodox Eastern Church. Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. 2. Orthodox Eastern Church. Prayer-books and devotions. 3. Prayers. I. Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia. 242.8019 Typeset in 11/12 point Garamond and 10/11 point SymbolGreek II (Linguist’s Software) CONTENTS Preface vii The Divine Liturgy 1 ïH Qeiva Leitourgiva Conclusion of Orthros 115 Tevlo" tou' ÒOrqrou Dismissal Hymns of the Resurrection 121 ÆApolutivkia ÆAnastavsima Dismissal Hymns of the Major Feasts 127 ÆApolutivkia tou' Dwdekaovrtou Other Hymns 137 Diavforoi ÓUmnoi Preparation for Holy Communion 141 Eujcai; pro; th'" Qeiva" Koinwniva" Thanksgiving after Holy Communion 151 Eujcaristiva meta; th;n Qeivan Koinwnivan Blessing of Loaves 165 ÆAkolouqiva th'" ÆArtoklasiva" Memorial Service 177 ÆAkolouqiva ejpi; Mnhmosuvnw/ v PREFACE The Divine Liturgy in English translation is published with the blessing of His Eminence Archbishop Stylianos of Australia. -

The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F

Valparaiso University ValpoScholar Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers Institute of Liturgical Studies 2017 The weT ntieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Liturgy and Worship Commons Recommended Citation Baldovin, John F. S.J., "The wT entieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects" (2017). Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers. 126. http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers/126 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Liturgical Studies at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin, S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry Introduction Metanoiete. From the very first word of Jesus recorded in the Gospel of Mark reform and renewal have been an essential feature of Christian life and thought – just as they were critical to the message of the prophets of ancient Israel. The preaching of the Gospel presumes at least some openness to change, to acting differently and to thinking about things differently. This process has been repeated over and over again over the centuries. This insight forms the backbone of Gerhard Ladner’s classic work The Idea of Reform, where renovatio and reformatio are constants throughout Christian history.1 All of the great reform movements in the past twenty centuries have been in response to both changing cultural and societal circumstances (like the adaptation of Christianity north of the Alps) and the failure of Christians individually and communally to live up to the demands of the Gospel. -

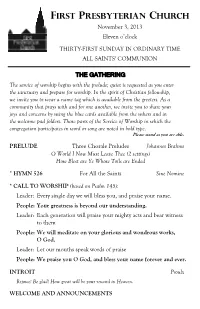

Ordinary 31C 11-3-2013 C&B.Pub

FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH November 3, 2013 Eleven o’clock THIRTY-FIRST SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME ALL SAINTS' COMMUNION THE GATHERING The service of worship begins with the prelude; quiet is requested as you enter the sanctuary and prepare for worship. In the spirit of Christian fellowship, we invite you to wear a name tag which is available from the greeters. As a community that prays with and for one another, we invite you to share your joys and concerns by using the blue cards available from the ushers and in the welcome pad folders. Those parts of the Service of Worship in which the congregation participates in word or song are noted in bold type. Please stand as you are able. PRELUDE Three Chorale Preludes Johannes Brahms O World I Now Must Leave Thee (2 settings) How Blest are Ye Whose Toils are Ended * HYMN 526 For All the Saints Sine Nomine * CALL TO WORSHIP (based on Psalm 145): Leader: Every single day we will bless you, and praise your name. People: Your greatness is beyond our understanding. Leader: Each generation will praise your mighty acts and bear witness to them People: We will meditate on your glorious and wondrous works, O God. Leader: Let our mouths speak words of praise People: We praise you O God, and bless your name forever and ever. INTROIT Proulx Rejoice! Be glad! How great will be your reward in Heaven. WELCOME AND ANNOUNCEMENTS CALL TO CONFESSION PRAYER OF CONFESSION Almighty God, we confess that we are unable to disentangle the good from the bad within us. -

R.E. Prayer Requirement Guidelines

R.E. Prayer Requirement Guidelines This year in the Religious Education Program we are re-instituting Prayer Requirements for each grade level. Please review the prayers required to be memorized, recited from text, \understood, or experienced for the grade that you are teaching (see p. 1) Each week, please take some class time to work on these prayers so that the R.E. students are able not only to recite the prayers but also to understand what they are saying and/or reading. The Student Sheet (p. 2) will need to be copied for each of your students, the student’s name placed on the sheet, and grid completed for each of the prayers they are expected to know, or understand, or recite from text, or experience. You may wish to assign the Assistant Catechist or High School Assistant to work, individually, with the students in order to assess their progress. We will be communicating these prayer requirements to the parents of your students, and later in the year, each student will take their sheet home for their parents to review their progress. We appreciate your assistance in teaching our youth to know their prayers and to pray often to Jesus… to adore God, to thank God, to ask God’s pardon, to ask God’s help in all things, to pray for all people. Remind your students that God always hears our prayers, but He does not always give us what we ask for because we do not always know what is best for others or ourselves. “Prayer is the desire and attempt to communicate with God.” Remember, no prayer is left unanswered! Prayer Requirements Table of Contents Page # Prayer Requirement List……………………………………. -

The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy

THE CONSTITUTION ON THE SACRED LITURGY Sacrosanctum Concilium, 4 December, 1963 INTRODUCTION 1. The sacred Council has set out to impart an ever-increasing vigor to the Christian life of the faithful; to adapt more closely to the needs of our age those institutions which are subject to change; to foster whatever can promote union among all who believe in Christ; to strengthen whatever can help to call all mankind into the Church's fold. Accordingly it sees particularly cogent reasons for undertaking the reform and promotion of the liturgy. 2. For it is the liturgy through which, especially in the divine sacrifice of the Eucharist, "the work of our redemption is accomplished,1 and it is through the liturgy, especially, that the faithful are enabled to express in their lives and manifest to others the mystery of Christ and the real nature of the true Church. The Church is essentially both human and divine, visible but endowed with invisible realities, zealous in action and dedicated to contemplation, present in the world, but as a pilgrim, so constituted that in her the human is directed toward and subordinated to the divine, the visible to the invisible, action to contemplation, and this present world to that city yet to come, the object of our quest.2 The liturgy daily builds up those who are in the Church, making of them a holy temple of the Lord, a dwelling-place for God in the Spirit,3 to the mature measure of the fullness of Christ.4 At the same time it marvelously increases their power to preach Christ and thus show forth the Church, a sign lifted up among the nations,5 to those who are outside, a sign under which the scattered children of God may be gathered together 6 until there is one fold and one shepherd.7 _______________________________________________________ 1. -

Reverenómo Er Mar Angeica

Mass of Christian Burial A n d Rite of Committal ReverenÓMoer MarAngeica of the Annunciation, P. C. P. A . Abbess Emerita, Our Lady of the Angels Monastery FRidAy, APRiL 1, 2016 Moer MarAngeica April 20, 1923 – March 27, 2016 Professed January 2, 1947 Mass of Christian Burial a n d Rite of Committal Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament Hanceville, Alabama Table of Contents I. Requiem Mass 3 The Guidelines for Reception of Holy Communion can be found on the inside back cover of this booklet. II. Solemn Procession and Rite of Committal 15 Introductory Rites Processional Requiem aeternam CHOIR Giovanni Martini (1706-1784); arr. Rev. Scott A. Haynes, S.J.C. Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) from Requiem ANT: Requiem aeternam dona ei ANT: Rest eternal grant unto her, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat ei. O Lord, and may light perpetual shine upon her. PS 130: De profundis clamavit ad te PS 130: Out of the depths I have cried to Domine… thee, O Lord... (CanticaNOVA, pub.) Kyrie Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison. R. Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Collect P. We humbly beseech your mercy, O Lord, for your servant Mother Mary Angelica, that, having worked tirelessly for the spread of the Gospel, she may merit to enter into the rewards of the Kingdom. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. R. Amen. 3 The Liturgy of the Word First Reading Book of Wisdom 3:1-9 He accepted them as a holocaust. -

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite Mass Structures Orientation Language The purpose of this presentation is to prepare you for what will very likely be your first Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is officially named “The Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” We will try to do that by comparing it to what you already know - the Novus Ordo Missae (NOM). This is officially named “The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” In “Mass Structures” we will look at differences in form. While the TLM really has only one structure, the NOM has many options. As we shall see, it has so many in fact, that it is virtually impossible for the person in the pew to determine whether the priest actually performs one of the many variations according to the rubrics (rules) for celebrating the NOM. Then, we will briefly examine the two most obvious differences in the performance of the Mass - the orientation of the priest (and people) and the language used. The orientation of the priest in the TLM is towards the altar. In this position, he is facing the same direction as the people, liturgical “east” and, in a traditional church, they are both looking at the tabernacle and/or crucifix in the center of the altar. The language of the TLM is, of course, Latin. It has been Latin since before the year 400. The NOM was written in Latin but is usually performed in the language of the immediate location - the vernacular. [email protected] 1 Mass Structure: Novus Ordo Missae Eucharistic Prayer Baptism I: A,B,C,D Renewal Eucharistic Prayer II: A,B,C,D Liturgy of Greeting: Penitential Concluding Dismissal: the Word: A,B,C Rite: A,B,C Eucharistic Prayer Rite: A,B,C A,B,C Year 1,2,3 III: A,B,C,D Eucharistic Prayer IV: A,B,C,D 3 x 4 x 3 x 16 x 3 x 3 = 5184 variations (not counting omissions) Or ~ 100 Years of Sundays This is the Mass that most of you attend. -

Mass Moment: Part 23 the EUCHARISTIC PRAYER (Anaphora)

5 Mass Moment: Part 23 THE EUCHARISTIC PRAYER (Anaphora). After the acclamation (the Holy, Holy, Holy), the congregation kneels while the priest, standing with arms outstretched, offers up the prayer (Anaphora) directly addressed to God the Father. This indicates even more clearly that the whole body directs its prayer to the Father only through its head, Christ. The Anaphora is the most solemn part of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, during which the offerings of bread and wine are consecrated as the body and blood of Christ. There are four main Eucharistic Prayers, also called Canon (I, II, III, IV). However, there are also four for Masses for Various Needs (I, II, III, IV) and two for Reconciliation (I, II). They are purely biblical in theology and in language, they possess a rich overtone from its Latin origins. It is important to note the elements that are central and uniform all through the various Eucharistic Prayers: the praise of God, thanksgiving, invocation of the Holy Spirit (also known as Epiclesis), the that is the up Christ our oblation to the Father through the Holy Spirit, then the doxology The first Canon is the longest and it includes the special communicates offering in union with the whole Church. The second Canon is the shortest and often used for daily Masses. It is said to be the oldest of the four Anaphoras by St. Hippolytus around 215 A.D. It has its own preface, but it also adapts and uses other prefaces too. The third Eucharistic Prayer is said to be based on the ancient Alexandrian, Byzantine, and Maronite Anaphoras, rich in sacrificial theology. -

Blood of Christ

THE BLOOD OF CHRIST R. B. THIEME, JR. R. B. THIEME, JR., BIBLE MINISTRIES HOUSTON, TEXAS F INANCIAL P OLICY There is no charge for any material from R. B. Thieme, Jr., Bible Ministries. Anyone who desires Bible teaching can receive our publications, DVDs, and MP3 CDs without obligation. God provides Bible doctrine. We wish to reflect His grace. R. B. Thieme, Jr., Bible Ministries is a grace ministry and operates entirely on voluntary contributions. There is no price list for any of our materials. No money is requested. When gratitude for the Word of God motivates a believer to give, he has the privilege of contributing to the dissemination of Bible doctrine. This book is edited from the lectures and unpublished notes of R. B. Thieme, Jr. A catalogue of available DVDs, MP3 CDs, and publications will be provided upon request. R. B. Thieme, Jr., Bible Ministries P. O. Box 460829, Houston, Texas 77056-8829 www.rbthieme.org © 2002, 1979, 1977, 1973, 1972 by R. B. Thieme, Jr. All rights reserved First edition published 1972. Fifth edition published 2002. Third impression 2015. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Scripture taken from the New American Standard Bible, © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 1-55764-036-X Contents Preface................................................ -

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I Prelude . Lighting of the Candles Greeting . Significance of the Day The Divine Service begins with the Hymn of Invocation (or the Processional Hymn, if there is a Procession), which helps set the tone and mood for the worship service, reminding us early on of God's great love through Jesus our Savior. Already, with the Prelude, the organist is directing our attention to the fact that in worship, "heaven touches earth," just as God's Word declares through the Virgin Mary in Luke 1:68: "Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, for He has visited and redeemed His people." Hymn of Invocation: CONFESSION AND ABSOLUTION Congregation shall stand The service continues as we invoke the name of the Triune God, put upon us by Jesus' command in our Baptism (Matthew 28:19) - the name in which we gather. St. Paul captures the eternal significance of our Baptism into Christ when he writes: "as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ" (Galatians 3:27). The sign of the cross may be made as a visible reminder of our Baptism. The congregation responds by saying, "Amen," which means "so let it be!” P In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. C Amen. The Exhortation is an invitation to confession. The inspired words of the Apostle John remind us that God is "faithful and just to forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness" (1 John 1:8-9). -

1 LET US PRAY – REFLECTIONS on the EUCHARIST Fr. Roger G. O'brien, Senior Priest, Archdiocese of Seattle

1 LET US PRAY – REFLECTIONS ON THE EUCHARIST Fr. Roger G. O’Brien, Senior Priest, Archdiocese of Seattle During this Year of the Eucharist, I offer a series of articles on Eucharistic Spirituality: Source of Life and Mission of our Church. Article #1, How We Name Eucharist. Let me make two initial remarks: one on how, in our long tradition, we have named the eucharist, and the other on eucharistic spirituality. We’ve given the eucharist a variety of names, in our church’s practice and tradition. The New Testament called it the Lord’s Supper (Paul so names it in 1 Cor. 11:20); and also the Breaking of the Bread (by Luke, in Acts 2:42,46). Later, a Greek designation was given it, Anamnesis, meaning “remembrance”. It is the remembrance, the memorial of the Lord, in which we actually participate in his dying and rising. Sometimes, it was called simply Communion, underscoring the unity we have with Jesus and one another when we eat the bread and drink the cup (1 Cor. 10:16). We speak of “doing eucharist” together because, in doing it, we have communion with the Lord and one another. Anglicans still use this name, today, to refer to the Lord’s Supper. We call it Eucharist – meaning “thanksgiving” (from the Greek, eucharistein, “to give thanks”). Jesus gave thanks at the Last Supper. And we do so. When we come together to be nourished in word and sacrament, we give thanks for Jesus’ dying and rising. It was also called Sacrifice. Early christian writers spoke of Jesus’ Sacrifice (also calling it his Offering), which was not only a gift received but also the gift whereby we approach God. -

The Chalice Francis’ AUGUST 2 0 1 9 Page 4: from the Bishop’S Warden

ST. FRANCIS’ EPISCOP A L C H U R C H IN THIS ISSUE E U R E K A , M O Page 1: Morning Coffee on the River Page 2: Search Committee Page 3: Friends of St. The Chalice Francis’ AUGUST 2 0 1 9 Page 4: From the Bishop’s Warden Page 5: Diocesan Elections; Feed the Morning Coffee on the River Need-STL Recently, I received word ing on open fires with the the boiling water into unwashed Page 6: Agape House; Potluck with Friends that an old friend from the smoke constantly shifting. All cups containing several Folgers Diocese of West Missouri was endured as we went Coffee Singles we would sit side Page 7: Food Pantry; Recipe died. We eventually lost track about our daily business of by side facing the river, watching of each other after Dayna and canoeing and having fun, the morning mist burn off with Page 8: Stump the Vicar; Interment of I moved to St. Louis. Permit mending cut fingers and toes the rising sun. Ashes me to share a story about the and caring for insect bites In the beginning of the week beginning of our friendship. we talked about the river and Page 9: Book Group; while we planted new seeds Eureka Days; Lunar July is a hot and sticky in the kingdom and watered camping and fishing. Then we Communion Sunday; month in the heartland of our those planted by others. began to talk about the campers Centering Prayer country. The sun beats down and Cliff Springs.