The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ordinary 31C 11-3-2013 C&B.Pub

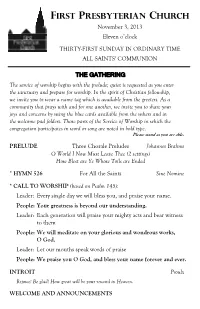

FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH November 3, 2013 Eleven o’clock THIRTY-FIRST SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME ALL SAINTS' COMMUNION THE GATHERING The service of worship begins with the prelude; quiet is requested as you enter the sanctuary and prepare for worship. In the spirit of Christian fellowship, we invite you to wear a name tag which is available from the greeters. As a community that prays with and for one another, we invite you to share your joys and concerns by using the blue cards available from the ushers and in the welcome pad folders. Those parts of the Service of Worship in which the congregation participates in word or song are noted in bold type. Please stand as you are able. PRELUDE Three Chorale Preludes Johannes Brahms O World I Now Must Leave Thee (2 settings) How Blest are Ye Whose Toils are Ended * HYMN 526 For All the Saints Sine Nomine * CALL TO WORSHIP (based on Psalm 145): Leader: Every single day we will bless you, and praise your name. People: Your greatness is beyond our understanding. Leader: Each generation will praise your mighty acts and bear witness to them People: We will meditate on your glorious and wondrous works, O God. Leader: Let our mouths speak words of praise People: We praise you O God, and bless your name forever and ever. INTROIT Proulx Rejoice! Be glad! How great will be your reward in Heaven. WELCOME AND ANNOUNCEMENTS CALL TO CONFESSION PRAYER OF CONFESSION Almighty God, we confess that we are unable to disentangle the good from the bad within us. -

What Is “Ad Orientem”? Why Is the Priest Celebrating with His When We All Celebrate Facing East, the Us to God

What is “Ad Orientem”? Why is the priest celebrating with his When we all celebrate facing East, the us to God. Look where he’s pointing, not back to us? He isn’t. He could only ‘have priest is part of the people, not separated at the one pointing. his back to us’, if we were the center of from them. He is their leader and Facing East reinforces the mystery his attention at Mass. But we aren’t, God representative before God and we are of the Mass. We have become so is. The priest is celebrating looking east, all one, together in our posture. Think familiar with the actions of the priest; in anticipation of the coming of Jesus. about all those battle we sometimes forget Remember the words of the Advent images of generals the great mystery at the hymn, People Look East? “People, look on horseback—they heart of it: that the priest East. The time is near of the crowning of are facing with their exercises his priesthood the year. Make your house fair as you are troops, not facing in Jesus Himself and it able, trim the hearth and set the table. against them. Just so, is Jesus really and truly People, look East and sing today: Love, the priest is visibly present both standing as the guest, is on the way.” part of the people and the priest and on the altar We have become so familiar to Mass clearly acts in persona as the sacrifice. When celebrated with the priest facing us that Christi capitis, “in the the priest bends low over we have forgotten that this is a relatively person of Christ the the elements and then new innovation both historically and head,” when we all face elevates, first the host and liturgically and actually something that the same direction. -

Issue 16 - January 2019

ARCHDIOCESE OF PORTLAND IN OREGON DivineBirth of ChristWorship - Giotto Newsletter From the West Window of Chartres Cathedral ISSUE 16 - JANUARY 2019 Welcome to the sixteenth Monthly Newsletter of the Office of Divine Worship of the Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon. We hope to provide news with regard to liturgical topics and events of interest to those in the Archdiocese who have a pastoral role that involves the Sacred Liturgy. The hope is that the priests of the Archdiocese will take a glance at this newsletter and share it with those in their parishes that are interested in the Sacred Liturgy. This Newsletter is now available through Apple in the iBooks Store and always available in pdf format on the Archdiocesan website. It will also be included in the weekly priests’ mailing. If you would like to be emailed a copy of this newsletter as soon as it is published please send your email address to Anne Marie Van Dyke at [email protected]. Just put DWNL in the subject field and we will add you to the mailing list. All past issues of the DWNL are available on the Divine Worship Webpage and in the iBooks Store. The answer to last month’s competition was St. Paul Outside the Walls - the first correct answer was submitted by Nichlas Schaal of St. Anthony Parish in Tigard. If you have a topic that you would like to see explained or addressed in this newsletter please feel free to email this office and we will try to answer your questions and treat topics that interest you and perhaps others who are concerned with Sacred Liturgy in the Archdiocese. -

Reverenómo Er Mar Angeica

Mass of Christian Burial A n d Rite of Committal ReverenÓMoer MarAngeica of the Annunciation, P. C. P. A . Abbess Emerita, Our Lady of the Angels Monastery FRidAy, APRiL 1, 2016 Moer MarAngeica April 20, 1923 – March 27, 2016 Professed January 2, 1947 Mass of Christian Burial a n d Rite of Committal Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament Hanceville, Alabama Table of Contents I. Requiem Mass 3 The Guidelines for Reception of Holy Communion can be found on the inside back cover of this booklet. II. Solemn Procession and Rite of Committal 15 Introductory Rites Processional Requiem aeternam CHOIR Giovanni Martini (1706-1784); arr. Rev. Scott A. Haynes, S.J.C. Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) from Requiem ANT: Requiem aeternam dona ei ANT: Rest eternal grant unto her, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat ei. O Lord, and may light perpetual shine upon her. PS 130: De profundis clamavit ad te PS 130: Out of the depths I have cried to Domine… thee, O Lord... (CanticaNOVA, pub.) Kyrie Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison. R. Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Collect P. We humbly beseech your mercy, O Lord, for your servant Mother Mary Angelica, that, having worked tirelessly for the spread of the Gospel, she may merit to enter into the rewards of the Kingdom. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. R. Amen. 3 The Liturgy of the Word First Reading Book of Wisdom 3:1-9 He accepted them as a holocaust. -

SACRED MUSIC Winter 2002 Volume 129 No.4

SACRED MUSIC Winter 2002 Volume 129 No.4 -~..~ " 1 ......... -- Cathedral and Campanile, Florence, Italy. SACRED MUSIC Volume 129, Number 4, Winter 2002 EDITORIAL 3 Kneeling for Holy Communion SIR RICHARD TERRY AND THE WESTMINSTER CATHEDRAL TRADITION 5 Leonardo J. Gajardo "ONE, HOLY, CATHOLIC AND APOSTOLIC?" 9 Joseph H. Foegen, Ph.D. NARROWING THE FACTUAL BASES OF THE AD ORIENTEM POSITION 13 Fr. Timothy Johnson KNEELING FOR COMMUNION IN AMERICA?-YES! 20 Two letters from Rome REVIEWS 22 OPEN FORUM 25 NEWS 25 CONTRIBUTORS 27 INDEX 28 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of Publication: 134 Christendom Drive, Front Royal, VA 22630-5103. E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Assistant: Christine Collins News: Kurt Poterack Music for Review: Calvert Shenk, Sacred Heart Major Seminary, 2701 West Chicago Blvd., Detroit, MI 48206 Susan Treacy, Dept. of Music, Franciscan University, Steubenville, OH 43952-6701 Membership, Circulation and Advertising: 5389 22nd Ave. SW, Naples, FL 34116 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Father Robert Skeris Vice-President Father Robert Pasley General Secretary Rosemary Reninger Treasurer Ralph Stewart Directors Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Stephen Becker Father Robert Pasley Kurt Poterack Rosemary Reninger Paul F. Salumunovich Rev. Robert A. Skeris Brian Franck Susan Treacy Calvert Shenk Monsignor Richard Schuler Ralph Stewart Membership in the Church Music Association of America includes a subscription to SACRED MUSIC. -

![The Catholic Mass[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6459/the-catholic-mass-1-236459.webp)

The Catholic Mass[1]

The Catholic Mass God wants you to encounter Him In the Church's liturgy the divine blessing is fully revealed and communicated. The Father is acknowledged and adored as the source and the end of all the blessings of creation and salvation. In his Word who became incarnate, died, and rose for us, he fills us with his blessings. Through his Word, he pours into our hearts the Gift that contains all gifts, the Holy Spirit. Catechism of the Catholic Church 1082 "Seated at the right hand of the Father" and pouring out the Holy Spirit on his Body which is the Church, Christ now acts through the sacraments he instituted to communicate his grace. The sacraments are perceptible signs (words and actions) accessible to our human nature. By the action of Christ and the power of the Holy Spirit they make present efficaciously the grace that they signify. Catechism of the Catholic Church 1084 In the liturgy of the New Covenant every liturgical action, especially the celebration of the Eucharist and the sacraments, is an encounter between Christ and the Church. The liturgical assembly derives its unity from the "communion of the Holy Spirit" who gathers the children of God into the one Body of Christ. This assembly transcends racial, cultural, social - indeed, all human affinities. Catechism of the Catholic Church 1097 Jesus is the Word of God made flesh. It is Him that is being proclaimed at Mass. He is present whether or not the lector knows how to pronounce the words, or is speaking clearly or is dynamic. -

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite Mass Structures Orientation Language The purpose of this presentation is to prepare you for what will very likely be your first Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is officially named “The Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” We will try to do that by comparing it to what you already know - the Novus Ordo Missae (NOM). This is officially named “The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” In “Mass Structures” we will look at differences in form. While the TLM really has only one structure, the NOM has many options. As we shall see, it has so many in fact, that it is virtually impossible for the person in the pew to determine whether the priest actually performs one of the many variations according to the rubrics (rules) for celebrating the NOM. Then, we will briefly examine the two most obvious differences in the performance of the Mass - the orientation of the priest (and people) and the language used. The orientation of the priest in the TLM is towards the altar. In this position, he is facing the same direction as the people, liturgical “east” and, in a traditional church, they are both looking at the tabernacle and/or crucifix in the center of the altar. The language of the TLM is, of course, Latin. It has been Latin since before the year 400. The NOM was written in Latin but is usually performed in the language of the immediate location - the vernacular. [email protected] 1 Mass Structure: Novus Ordo Missae Eucharistic Prayer Baptism I: A,B,C,D Renewal Eucharistic Prayer II: A,B,C,D Liturgy of Greeting: Penitential Concluding Dismissal: the Word: A,B,C Rite: A,B,C Eucharistic Prayer Rite: A,B,C A,B,C Year 1,2,3 III: A,B,C,D Eucharistic Prayer IV: A,B,C,D 3 x 4 x 3 x 16 x 3 x 3 = 5184 variations (not counting omissions) Or ~ 100 Years of Sundays This is the Mass that most of you attend. -

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I Prelude . Lighting of the Candles Greeting . Significance of the Day The Divine Service begins with the Hymn of Invocation (or the Processional Hymn, if there is a Procession), which helps set the tone and mood for the worship service, reminding us early on of God's great love through Jesus our Savior. Already, with the Prelude, the organist is directing our attention to the fact that in worship, "heaven touches earth," just as God's Word declares through the Virgin Mary in Luke 1:68: "Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, for He has visited and redeemed His people." Hymn of Invocation: CONFESSION AND ABSOLUTION Congregation shall stand The service continues as we invoke the name of the Triune God, put upon us by Jesus' command in our Baptism (Matthew 28:19) - the name in which we gather. St. Paul captures the eternal significance of our Baptism into Christ when he writes: "as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ" (Galatians 3:27). The sign of the cross may be made as a visible reminder of our Baptism. The congregation responds by saying, "Amen," which means "so let it be!” P In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. C Amen. The Exhortation is an invitation to confession. The inspired words of the Apostle John remind us that God is "faithful and just to forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness" (1 John 1:8-9). -

An Outline of a Eucharistic Prayer

An Outline of a Eucharistic Prayer The Eucharistic Prayers used in the Episcopal Church are based on an ancient outline of prayer found in something called “The Text of Hippolytus.” Though the actual words of the eucharistic prayer may vary, every eucharistic prayer contains the same elements. Presider: The Lord be with you. The opening versicles and responses. Here the People: And also with you. presider greets the congregation, reminds them of the joyous purpose that brings us to the table, Presider: Lift up your hearts. and then asks their permission to offer the People: We lift them up to the Lord. eucharistic prayer on their behalf. Known as the “Sursum Corda,” meaning “Lift up your hearts.” Presider: Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. People: It is right to give God thanks and praise. Presider: Good morning, Lord. We are Eucharistic prayers generally include a short your people, gathered at your table to give your recitation of salvation history. Here, the prayer thanks and praise. Thank you for always gives thanks for the ways God reveals God’s self, revealing yourself: in Creation; in your people, fully and completely in Jesus, the Word made gathered and sent; in your Word spoken through flesh. While sometimes the eucharistic prayer the Scriptures; and above all in the Word made may emphasize the offering made on the cross, flesh, Jesus, your Son. You sent him to be this one emphasizes the incarnation…God incarnate from the Virgin Mary, to be the Savior becoming human in Jesus Christ. and Redeemer of the world. -

The Liturgical Movement and Reformed Worship 13

The Liturgical Movement and Reformed Worship 13 The Liturgical Movement and Reformed Worship COMING across a certain liturgical monstrosity, a Scottish Churchman asked : " What Irishman perpetrated this ? " Greatly daring therefore, the writer, though Irish, because the Irishman turned out to be an American, confines his remarks in this paper to the Scottish Eucharistic Rite, as limitations of space prevent discussion of other Reformed movements on the Continent, in England, Ireland, America, and elsewhere. The aim of the Reformers concerning the Eucharistic Rite was threefold : (i) Reform of the rite. The earliest Reformed rites were based on the Hagenau Missal, and their lineage through Schwarz, Bucer, Calvin, and Knox is traced by Hubert, Smend, Albertz, and W. D. Maxwell. (ii) That the worshippers should be active participants in the rite. This was achieved principally by the use of the vernacular and the introduction of congregational singing. (iii) Weekly communion. This ideal failed because of medieval legacy and the interference of civil authority, so that quarterly communion became the general practice. Public worship, however, when there was no celebration, was based on the eucharistic norm. The second half of the seventeenth century, and the eighteenth century, proved to be a period of decline and poverty in worship, and liturgical renewal in Scotland only began in the nineteenth century. This falls into four periods. (a) Prior to 1865, when it was principally the work of individuals. (b) After 1865, when the Church Service Society was founded and the principal leaders were G. W. Sprott and Thomas Leishman, both of whom knew their history. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA the Missa Chrismatis: a Liturgical Theology a DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the S

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Missa Chrismatis: A Liturgical Theology A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Sacred Theology © Copyright All rights reserved By Seth Nater Arwo-Doqu Washington, DC 2013 The Missa Chrismatis: A Liturgical Theology Seth Nater Arwo-Doqu, S.T.D. Director: Kevin W. Irwin, S.T.D. The Missa Chrismatis (“Chrism Mass”), the annual ritual Mass that celebrates the blessing of the sacramental oils ordinarily held on Holy Thursday morning, was revised in accordance with the decrees of Vatican II and promulgated by the authority of Pope Paul VI and inserted in the newly promulgated Missale Romanum in 1970. Also revised, in tandem with the Missa Chrismatis, is the Ordo Benedicendi Oleum Catechumenorum et Infirmorum et Conficiendi Chrisma (Ordo), and promulgated editio typica on December 3, 1970. Based upon the scholarly consensus of liturgical theologians that liturgical events are acts of theology, this study seeks to delineate the liturgical theology of the Missa Chrismatis by applying the method of liturgical theology proposed by Kevin Irwin in Context and Text. A critical study of the prayers, both ancient and new, for the consecration of Chrism and the blessing of the oils of the sick and of catechumens reveals rich theological data. In general it can be said that the fundamental theological principle of the Missa Chrismatis is initiatory and consecratory. The study delves into the history of the chrismal liturgy from its earliest foundations as a Mass in the Gelasianum Vetus, including the chrismal consecration and blessing of the oils during the missa in cena domini, recorded in the Hadrianum, Ordines Romani, and Pontificales Romani of the Middle Ages, through the reforms of 1955-56, 1965 and, finally, 1970. -

Roman Catholic Liturgical Renewal Forty-Five Years After Sacrosanctum Concilium: an Assessment KEITH F

Roman Catholic Liturgical Renewal Forty-Five Years after Sacrosanctum Concilium: An Assessment KEITH F. PECKLERS, S.J. Next December 4 will mark the forty-fifth anniversary of the promulgation of the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, which the Council bishops approved with an astounding majority: 2,147 in favor and 4 opposed. The Constitution was solemnly approved by Pope Paul VI—the first decree to be promulgated by the Ecumenical Council. Vatican II was well aware of change in the world—probably more so than any of the twenty ecumenical councils that preceded it.1 It had emerged within the complex social context of the Cuban missile crisis, a rise in Communism, and military dictatorships in various corners of the globe. President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated only twelve days prior to the promulgation of Sacrosanctum Concilium.2 Despite those global crises, however, the Council generally viewed the world positively, and with a certain degree of optimism. The credibility of the Church’s message would necessarily depend on its capacity to reach far beyond the confines of the Catholic ghetto into the marketplace, into non-Christian and, indeed, non-religious spheres.3 It is important that the liturgical reforms be examined within such a framework. The extraordinary unanimity in the final vote on the Constitution on the Liturgy was the fruit of the fifty-year liturgical movement that had preceded the Council. The movement was successful because it did not grow in isolation but rather in tandem with church renewal promoted by the biblical, patristic, and ecumenical movements in that same historical period.