Drink out of It All of You”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F

Valparaiso University ValpoScholar Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers Institute of Liturgical Studies 2017 The weT ntieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Liturgy and Worship Commons Recommended Citation Baldovin, John F. S.J., "The wT entieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects" (2017). Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers. 126. http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers/126 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Liturgical Studies at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin, S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry Introduction Metanoiete. From the very first word of Jesus recorded in the Gospel of Mark reform and renewal have been an essential feature of Christian life and thought – just as they were critical to the message of the prophets of ancient Israel. The preaching of the Gospel presumes at least some openness to change, to acting differently and to thinking about things differently. This process has been repeated over and over again over the centuries. This insight forms the backbone of Gerhard Ladner’s classic work The Idea of Reform, where renovatio and reformatio are constants throughout Christian history.1 All of the great reform movements in the past twenty centuries have been in response to both changing cultural and societal circumstances (like the adaptation of Christianity north of the Alps) and the failure of Christians individually and communally to live up to the demands of the Gospel. -

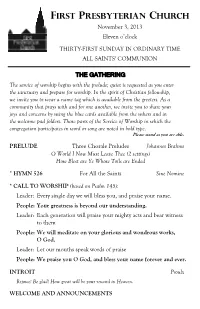

Ordinary 31C 11-3-2013 C&B.Pub

FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH November 3, 2013 Eleven o’clock THIRTY-FIRST SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME ALL SAINTS' COMMUNION THE GATHERING The service of worship begins with the prelude; quiet is requested as you enter the sanctuary and prepare for worship. In the spirit of Christian fellowship, we invite you to wear a name tag which is available from the greeters. As a community that prays with and for one another, we invite you to share your joys and concerns by using the blue cards available from the ushers and in the welcome pad folders. Those parts of the Service of Worship in which the congregation participates in word or song are noted in bold type. Please stand as you are able. PRELUDE Three Chorale Preludes Johannes Brahms O World I Now Must Leave Thee (2 settings) How Blest are Ye Whose Toils are Ended * HYMN 526 For All the Saints Sine Nomine * CALL TO WORSHIP (based on Psalm 145): Leader: Every single day we will bless you, and praise your name. People: Your greatness is beyond our understanding. Leader: Each generation will praise your mighty acts and bear witness to them People: We will meditate on your glorious and wondrous works, O God. Leader: Let our mouths speak words of praise People: We praise you O God, and bless your name forever and ever. INTROIT Proulx Rejoice! Be glad! How great will be your reward in Heaven. WELCOME AND ANNOUNCEMENTS CALL TO CONFESSION PRAYER OF CONFESSION Almighty God, we confess that we are unable to disentangle the good from the bad within us. -

Declaration on the Way Church, Ministry, and Eucharist

Declaration on the Way Church, Ministry, and Eucharist Committee on Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Copyright © 2015 Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Published by Augsburg Fortress. Permission is granted to download and reproduce a single copy of this publication for individual, non-commercial use. Copies for group use and study are available for purchase at www.augsburgfortress.org. Please direct other permission requests to [email protected]. Augsburg Fortress Minneapolis DECLARATION ON THE WAY Church, Ministry, and Eucharist Copyright © 2015 Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of Augs- burg Fortress, PO Box 1209, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55440 or United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 3211 Fourth Street NE, Wash- ington, DC 20017. Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover art: The Road to Emmaus by He Qi (www.heqiart.com) Cover design: Laurie Ingram Book design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Print ISBN: 978-1-5064-1616-8 eBook ISBN: 978-1-5064-1617-5 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z329.48-1984. -

Reverenómo Er Mar Angeica

Mass of Christian Burial A n d Rite of Committal ReverenÓMoer MarAngeica of the Annunciation, P. C. P. A . Abbess Emerita, Our Lady of the Angels Monastery FRidAy, APRiL 1, 2016 Moer MarAngeica April 20, 1923 – March 27, 2016 Professed January 2, 1947 Mass of Christian Burial a n d Rite of Committal Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament Hanceville, Alabama Table of Contents I. Requiem Mass 3 The Guidelines for Reception of Holy Communion can be found on the inside back cover of this booklet. II. Solemn Procession and Rite of Committal 15 Introductory Rites Processional Requiem aeternam CHOIR Giovanni Martini (1706-1784); arr. Rev. Scott A. Haynes, S.J.C. Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) from Requiem ANT: Requiem aeternam dona ei ANT: Rest eternal grant unto her, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat ei. O Lord, and may light perpetual shine upon her. PS 130: De profundis clamavit ad te PS 130: Out of the depths I have cried to Domine… thee, O Lord... (CanticaNOVA, pub.) Kyrie Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison. R. Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Collect P. We humbly beseech your mercy, O Lord, for your servant Mother Mary Angelica, that, having worked tirelessly for the spread of the Gospel, she may merit to enter into the rewards of the Kingdom. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. R. Amen. 3 The Liturgy of the Word First Reading Book of Wisdom 3:1-9 He accepted them as a holocaust. -

Quality Silversmiths Since 1939. SPAIN

Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com - ARTIMETAL - PROCESSIONALIA 2014-2015 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN ARTISTIC SILVER INDEXINDEX Presentation ......................................................................................... Pag. 1-12 ARTISTIC SILVER - ARTIMETAL ARTISTICPresentation SILVER & ARTIMETAL Pag. 1-12 ChalicesChalices && CiboriaCiboria ........................................................................... Pag. 13-6713-52 MonstrancesCruet Sets & Ostensoria ...................................................... Pag. 68-7853 TabernaclesJug & Basin,........................................................................................... Buckets Pag. 79-9654 AltarMonstrances accessories & Ostensoria Pag. 55-63 &Professional Bishop’s appointments Crosses ......................................................... Pag. 97-12264 Tabernacles Pag. 65-80 PROCESIONALIAAltar accessories ............................................................................. Pag. 123-128 & Bishop’s appointments Pag. 81-99 General Information ...................................................................... Pag. 129-132 ARTIMETAL Chalices & Ciboria Pag. 101-115 Monstrances Pag. 116-117 Tabernacles Pag. 118-119 Altar accessories Pag. 120-124 PROCESIONALIA Pag. 125-130 General Information Pag. 131-134 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. Justo Dorado, 12 28040 Madrid, Spain Product design: Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. CHALICES & CIBORIA Our silversmiths combine -

The Sacramental Presence in Lutheran Orthodoxy

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY APRIL 1986 Catholicity and Catholicism . .Avery DuIles 81 The !baamental Presence in Luthetrin Orthodoxy. .Eugene F. Klug 95 Toward a New -ran I,ognWics . .Lawell C. Gnxn 109 The Curious Histories of the Wittenberg Concord . .James M. Kittelson with Ken Schurb 119 The Sacramental Presence in Lutheran Orthodoxy Eugene E Klug For Luther the doctrine of the Real Presence was one of the crucial issues of the Reformation. There is no way of understand- ing what went on in the years following his death, particularly in the lives and theology of the orthodox teachers of the Lutheran church, unless the platform on which Luther stood is clearly recog- nized. Luther had gone to the Marburg colioquy of 1529 with minimal expectations. In later years he reflected on the outcome of that discussion with Zwingli, noting that in spite of everything there had been considerable convergence except on the presence of Christ's body and blood in the Sacrament. These thoughts are contained in his BriefCor&ssionconcerning the Holy Sacmment of 1544. "With considerable hope we departed from Marburg:' Luther comments, "because they agreed to all the Christian articles of the faith:' and even "in this article of the holy sacrament they also abandoned their previous error" (that it was merely bread), and "it seemed as if they would in time share our point of view altogether!" This result was not to be, as history records. With all the might that was in him Luther protested loudly throughout his life against any diminution of Christ's body and blood in the Sacrament.' Probably none of Luther's works played as large a role as did his famous "Great Confession" of 1528, the Co~kssionconcerning Christ's Supper. -

Eucharistic Practice & Sacramental Theology in Pandemic Times

The essential nature of the Eucharist and the modes of its reception DAVID N. BELL & JOHN COURAGE ON BEHALF OF QUEEN’S COLLEGE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY he Faculty of Theology at Queen’s College held two well-attended T consultative sessions by means of GoToMeeting on June 15 and June 22, 2020. The discussions were lively and informative, and alt- hough a great deal of ground was covered, there were three questions of major concern. All three pertain directly to the nature and reception of the Eucharist during the present pandemic. First, how inclusive should the Eucharist be? Or, putting it another way, who constitutes the Body of Christ at the Lord’s Table? Secondly, since the physical reception of the Eucharist – the bread and the wine – is precluded at the present time, in what way or ways can we understand its spiritual reception? And thirdly, can the Eucharist act in a similar way to an icon, namely, as a window connecting this world with the transfigured cosmos? The overwhelming opinion of those present at both sessions was that the Eucharist, which is a multi-faceted celebration, should be as inclusive as possible, and that – once the physical reception is again made possible – no one who presents themselves at the altar should be refused. It is not the business of any member of the clergy to try to channel God’s grace and, as a consequence, anyone who wishes to receive communion should do so – what happens after that is entirely up to God. All those, therefore, who par- ticipate in any form of online worship may be regarded as belonging to the Body of Christ, and we must remember that Christ himself said that he had many sheep which were not of this fold (Jn 10:16). -

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I Prelude . Lighting of the Candles Greeting . Significance of the Day The Divine Service begins with the Hymn of Invocation (or the Processional Hymn, if there is a Procession), which helps set the tone and mood for the worship service, reminding us early on of God's great love through Jesus our Savior. Already, with the Prelude, the organist is directing our attention to the fact that in worship, "heaven touches earth," just as God's Word declares through the Virgin Mary in Luke 1:68: "Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, for He has visited and redeemed His people." Hymn of Invocation: CONFESSION AND ABSOLUTION Congregation shall stand The service continues as we invoke the name of the Triune God, put upon us by Jesus' command in our Baptism (Matthew 28:19) - the name in which we gather. St. Paul captures the eternal significance of our Baptism into Christ when he writes: "as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ" (Galatians 3:27). The sign of the cross may be made as a visible reminder of our Baptism. The congregation responds by saying, "Amen," which means "so let it be!” P In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. C Amen. The Exhortation is an invitation to confession. The inspired words of the Apostle John remind us that God is "faithful and just to forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness" (1 John 1:8-9). -

An Outline of a Eucharistic Prayer

An Outline of a Eucharistic Prayer The Eucharistic Prayers used in the Episcopal Church are based on an ancient outline of prayer found in something called “The Text of Hippolytus.” Though the actual words of the eucharistic prayer may vary, every eucharistic prayer contains the same elements. Presider: The Lord be with you. The opening versicles and responses. Here the People: And also with you. presider greets the congregation, reminds them of the joyous purpose that brings us to the table, Presider: Lift up your hearts. and then asks their permission to offer the People: We lift them up to the Lord. eucharistic prayer on their behalf. Known as the “Sursum Corda,” meaning “Lift up your hearts.” Presider: Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. People: It is right to give God thanks and praise. Presider: Good morning, Lord. We are Eucharistic prayers generally include a short your people, gathered at your table to give your recitation of salvation history. Here, the prayer thanks and praise. Thank you for always gives thanks for the ways God reveals God’s self, revealing yourself: in Creation; in your people, fully and completely in Jesus, the Word made gathered and sent; in your Word spoken through flesh. While sometimes the eucharistic prayer the Scriptures; and above all in the Word made may emphasize the offering made on the cross, flesh, Jesus, your Son. You sent him to be this one emphasizes the incarnation…God incarnate from the Virgin Mary, to be the Savior becoming human in Jesus Christ. and Redeemer of the world. -

THE REAL PRESENCE of CHRIST's BODY and BLOOD in the LORD's SUPPER: Contemporary Issues Concerning the Sacramental Union

THE REAL PRESENCE OF CHRIST'S BODY AND BLOOD IN THE LORD'S SUPPER: Contemporary Issues Concerning The Sacramental Union The great importance of the Lord's Supper is indicated by the fact that it is one of the few events of our Savior’s ministry which is recorded four times in the Holy Scriptures. Literally translated, these passages read: Matthew 26:26-28 jEsqiovntwn de; aujtw'n labw;n oJ jIhsou'" a[rton kai; eujloghvsa" e[klasen kai; dou;" toi'" maqhtai'" ei\pen: lavbete favgete, tou'to ejstin to; sw'ma mou. kai; labw;n pothvrion kai; eujcaristhvsa" e[dwken aujtoi'" levgwn: pivete ejx aujtou' pavnte", tou'to gavr ejstin to; ai|ma mou th'" diaqhvkh" to; peri; pollw'n 1 ejkcunnovmenon eij" a[fesin aJmartiw'n. While they were eating, Jesus, after he had taken bread and blessed [it], he broke [it] and, after he had given [it] to the disciples, he said, "Take, eat. This is my body.” And after he had taken a cup and given thanks, he gave [it] to them, saying, "Drink from it, all of you, for this is my blood of the covenant, which is being poured out for many unto the forgiveness of sins. Mark 14:22-24. Kai; ejsqiovntwn aujtw'n labw;n a[rton eujloghvsa" e[klasen kai; e[dwken aujtoi'" kai; ei\pen: lavbete, tou'to ejstin to; sw'ma mou. kai; labw;n pothvrion eujcaristhvsa" e[dwken aujtoi'", kai; e[pion ejx aujtou' pavnte". kai; ei\pen aujtoi'": tou'to ejstin to; ai|ma mou th'" diaqhvkh" to; ejkcunnovmenon uJpe;r pollw'n. -

Flu Season Disease Prevention & Practices for Worshiping

Flu Season Disease Prevention & Practices For Worshiping Communities Episcopal Diocese of Michigan October 2009 (updated January 2014) The H1N1 strain of influenza is in our midst (again). Public health officials continue to strongly encourage everyone to be prepared for this and other forms of influenza (the flu). We encourage all congregations and communities of faith to develop a plan in light of this, and are reissuing this update to both encourage and remind. If you have not already, you may want to bring together a group of people at your parish to begin discussing what might be best for your parishioners. There may be some steps you might want to put into place now, additional steps you may want to implement under more advanced circumstances. The guidance contained in this document is not a directive from the Diocese but simply a list of suggestions for accommodations you may wish to consider. Blessings & peace, The Right Reverend Wendell N. Gibbs, Jr., Bishop of Michigan Following a general overview, this resource will speak first to issues involving worship, particularly the administration of Holy Communion, and then with some considerations regarding pastoral visitation; large gatherings and staff practices. General Overview First, we strongly encourage getting both the seasonal flu vaccine. (As of this update the currently available flu vaccines include H1N1 in the compounding) This is especially true if 1) you fall into any of the special risk categories (some of which are pregnant women, children 6 month to 24 years old, those with chronic respiratory or heart conditions) and 2) you regularly visit in health care facilities, childcare/school settings, are a caregiver yourself, or live with anyone who is vulnerable to flu. -

Sign and Word: Martin Luther's Theology of the Sacraments

Restoration Quarterly Volume 32 Number 3 Article 1 7-1-1990 Sign and Word: Martin Luther's Theology of the Sacraments Kenneth R. Craycraft Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Craycraft, Kenneth R. Jr. (1990) "Sign and Word: Martin Luther's Theology of the Sacraments," Restoration Quarterly: Vol. 32 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly/vol32/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Restoration Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ ACU. VOLUME 32/NUMBER 3 THIRD QUARTER 1990 ResLoROt=ton _ aa1<Le1<lcY Sign and Word: Martin Luther's Theology of the Sacraments Kenneth R. Craycraft, Jr. Waltham, Massachusetts The study of any aspect of Martin Luther's theology must be seen in its historical context. While it may confidently be maintained that Luther presented fresh ideas and new approaches to doing theology, 1 it must also be said that much of his work was in reaction to what went on around him. This, at times, is a weakness. One can better understand Luther's system if one sees it in juxtaposition to others who were writing at the time. This explains to some extent the polemical emphasis that is present in much of his writing.2 Luther was often writing in response to what he saw as improper doctrine being taught by others.