Aspects of Epiclesis in the Roman Mass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F

Valparaiso University ValpoScholar Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers Institute of Liturgical Studies 2017 The weT ntieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Liturgy and Worship Commons Recommended Citation Baldovin, John F. S.J., "The wT entieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects" (2017). Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers. 126. http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers/126 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Liturgical Studies at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin, S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry Introduction Metanoiete. From the very first word of Jesus recorded in the Gospel of Mark reform and renewal have been an essential feature of Christian life and thought – just as they were critical to the message of the prophets of ancient Israel. The preaching of the Gospel presumes at least some openness to change, to acting differently and to thinking about things differently. This process has been repeated over and over again over the centuries. This insight forms the backbone of Gerhard Ladner’s classic work The Idea of Reform, where renovatio and reformatio are constants throughout Christian history.1 All of the great reform movements in the past twenty centuries have been in response to both changing cultural and societal circumstances (like the adaptation of Christianity north of the Alps) and the failure of Christians individually and communally to live up to the demands of the Gospel. -

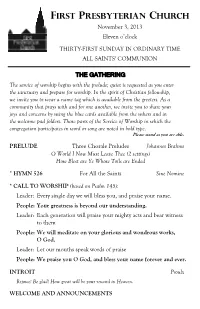

Ordinary 31C 11-3-2013 C&B.Pub

FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH November 3, 2013 Eleven o’clock THIRTY-FIRST SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME ALL SAINTS' COMMUNION THE GATHERING The service of worship begins with the prelude; quiet is requested as you enter the sanctuary and prepare for worship. In the spirit of Christian fellowship, we invite you to wear a name tag which is available from the greeters. As a community that prays with and for one another, we invite you to share your joys and concerns by using the blue cards available from the ushers and in the welcome pad folders. Those parts of the Service of Worship in which the congregation participates in word or song are noted in bold type. Please stand as you are able. PRELUDE Three Chorale Preludes Johannes Brahms O World I Now Must Leave Thee (2 settings) How Blest are Ye Whose Toils are Ended * HYMN 526 For All the Saints Sine Nomine * CALL TO WORSHIP (based on Psalm 145): Leader: Every single day we will bless you, and praise your name. People: Your greatness is beyond our understanding. Leader: Each generation will praise your mighty acts and bear witness to them People: We will meditate on your glorious and wondrous works, O God. Leader: Let our mouths speak words of praise People: We praise you O God, and bless your name forever and ever. INTROIT Proulx Rejoice! Be glad! How great will be your reward in Heaven. WELCOME AND ANNOUNCEMENTS CALL TO CONFESSION PRAYER OF CONFESSION Almighty God, we confess that we are unable to disentangle the good from the bad within us. -

Reverenómo Er Mar Angeica

Mass of Christian Burial A n d Rite of Committal ReverenÓMoer MarAngeica of the Annunciation, P. C. P. A . Abbess Emerita, Our Lady of the Angels Monastery FRidAy, APRiL 1, 2016 Moer MarAngeica April 20, 1923 – March 27, 2016 Professed January 2, 1947 Mass of Christian Burial a n d Rite of Committal Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament Hanceville, Alabama Table of Contents I. Requiem Mass 3 The Guidelines for Reception of Holy Communion can be found on the inside back cover of this booklet. II. Solemn Procession and Rite of Committal 15 Introductory Rites Processional Requiem aeternam CHOIR Giovanni Martini (1706-1784); arr. Rev. Scott A. Haynes, S.J.C. Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) from Requiem ANT: Requiem aeternam dona ei ANT: Rest eternal grant unto her, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat ei. O Lord, and may light perpetual shine upon her. PS 130: De profundis clamavit ad te PS 130: Out of the depths I have cried to Domine… thee, O Lord... (CanticaNOVA, pub.) Kyrie Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison. R. Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Collect P. We humbly beseech your mercy, O Lord, for your servant Mother Mary Angelica, that, having worked tirelessly for the spread of the Gospel, she may merit to enter into the rewards of the Kingdom. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. R. Amen. 3 The Liturgy of the Word First Reading Book of Wisdom 3:1-9 He accepted them as a holocaust. -

Mass Moment: Part 23 the EUCHARISTIC PRAYER (Anaphora)

5 Mass Moment: Part 23 THE EUCHARISTIC PRAYER (Anaphora). After the acclamation (the Holy, Holy, Holy), the congregation kneels while the priest, standing with arms outstretched, offers up the prayer (Anaphora) directly addressed to God the Father. This indicates even more clearly that the whole body directs its prayer to the Father only through its head, Christ. The Anaphora is the most solemn part of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, during which the offerings of bread and wine are consecrated as the body and blood of Christ. There are four main Eucharistic Prayers, also called Canon (I, II, III, IV). However, there are also four for Masses for Various Needs (I, II, III, IV) and two for Reconciliation (I, II). They are purely biblical in theology and in language, they possess a rich overtone from its Latin origins. It is important to note the elements that are central and uniform all through the various Eucharistic Prayers: the praise of God, thanksgiving, invocation of the Holy Spirit (also known as Epiclesis), the that is the up Christ our oblation to the Father through the Holy Spirit, then the doxology The first Canon is the longest and it includes the special communicates offering in union with the whole Church. The second Canon is the shortest and often used for daily Masses. It is said to be the oldest of the four Anaphoras by St. Hippolytus around 215 A.D. It has its own preface, but it also adapts and uses other prefaces too. The third Eucharistic Prayer is said to be based on the ancient Alexandrian, Byzantine, and Maronite Anaphoras, rich in sacrificial theology. -

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I Prelude . Lighting of the Candles Greeting . Significance of the Day The Divine Service begins with the Hymn of Invocation (or the Processional Hymn, if there is a Procession), which helps set the tone and mood for the worship service, reminding us early on of God's great love through Jesus our Savior. Already, with the Prelude, the organist is directing our attention to the fact that in worship, "heaven touches earth," just as God's Word declares through the Virgin Mary in Luke 1:68: "Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, for He has visited and redeemed His people." Hymn of Invocation: CONFESSION AND ABSOLUTION Congregation shall stand The service continues as we invoke the name of the Triune God, put upon us by Jesus' command in our Baptism (Matthew 28:19) - the name in which we gather. St. Paul captures the eternal significance of our Baptism into Christ when he writes: "as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ" (Galatians 3:27). The sign of the cross may be made as a visible reminder of our Baptism. The congregation responds by saying, "Amen," which means "so let it be!” P In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. C Amen. The Exhortation is an invitation to confession. The inspired words of the Apostle John remind us that God is "faithful and just to forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness" (1 John 1:8-9). -

An Outline of a Eucharistic Prayer

An Outline of a Eucharistic Prayer The Eucharistic Prayers used in the Episcopal Church are based on an ancient outline of prayer found in something called “The Text of Hippolytus.” Though the actual words of the eucharistic prayer may vary, every eucharistic prayer contains the same elements. Presider: The Lord be with you. The opening versicles and responses. Here the People: And also with you. presider greets the congregation, reminds them of the joyous purpose that brings us to the table, Presider: Lift up your hearts. and then asks their permission to offer the People: We lift them up to the Lord. eucharistic prayer on their behalf. Known as the “Sursum Corda,” meaning “Lift up your hearts.” Presider: Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. People: It is right to give God thanks and praise. Presider: Good morning, Lord. We are Eucharistic prayers generally include a short your people, gathered at your table to give your recitation of salvation history. Here, the prayer thanks and praise. Thank you for always gives thanks for the ways God reveals God’s self, revealing yourself: in Creation; in your people, fully and completely in Jesus, the Word made gathered and sent; in your Word spoken through flesh. While sometimes the eucharistic prayer the Scriptures; and above all in the Word made may emphasize the offering made on the cross, flesh, Jesus, your Son. You sent him to be this one emphasizes the incarnation…God incarnate from the Virgin Mary, to be the Savior becoming human in Jesus Christ. and Redeemer of the world. -

The Anaphora of the Apostles: Implications of the Mar Ε§Αύα Text Emmanuel J

THE ANAPHORA OF THE APOSTLES: IMPLICATIONS OF THE MAR Ε§ΑΎΑ TEXT EMMANUEL J. CUTRONE Quincy College, Illinois ike Russia, the East Syrian anaphora of the apostles Addai and Mari IJ qualifies as both mystery and enigma. The research done on the many mysteries of this third-eentury East Syrian anaphora usually clarifies all too sharply the many enigmas that still remain.1 Unlike other anaphoras which share its antiquity—Hippolytus, Apostolic Constitutions 8, Serapion, or the earlier witness of Justin—Addai and Mari is not a prototype academic exercise of a typical Eucharistie prayer.2 This anaphora was, and continues to be, an actual prayer of a worshiping community. Bouyer feels that "everything leads us to believe that this prayer is the most ancient christian eucharistie com- 1 Here is a listing of the major studies done on the Anaphora of the Apostles Addai and Mari: Bernard Botte, "L'Anaphore chaldéenne des apôtres," Orientalin Christiana periodica 15 (1949) 259-76; Β. Botte, "L'Epielèse dans les liturgies syriennes orientales," Sacris erudiri 6 (1954) 48-72; B. Botte, "Problème de l'anaphore syrienne des apôtres Addai et Mari," L'Orient syrien 10 (1965) 89-106; Louis Bouyer, Eucharist: Theology and Spirituality of the Eucharistie Prayer, tr. Charles Quinn (Notre Dame, Ind., 1966) pp. 146-57; Hieronymus Engberding, "Zum anaphorischen Fürbittgebet des ostsyrischen Liturgie Addaj und Mar(j)," Oriens christianus 41 (1957) 102-24; S. H. Jammo, "Gabriel Qatraya et son commentaire sur la liturgie chaldéenne," Orientalia Christiana periodica 32 (1966) 39-52; William F. Macomber, "The Oldest Known Text of the Anaphora of the Apostles Addai and Mari," ibid. -

Teaching Versus Anamnēsis in the Philosophy Of

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1994 The Word of the Other: Teaching Versus Anamnesis̄ in the Philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas Norman Wirzba Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Wirzba, Norman, "The Word of the Other: Teaching Versus Anamnesis̄ in the Philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas" (1994). Dissertations. 3449. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3449 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1994 Norman Wirzba Norman Wirzba Loyola University of Chicago THE WORD OF THE OTHER: TEACHING VERSUS ANAMNESIS IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF EMMANUEL LEVINAS Socratic philosophy represents a long-standing tradition within philosophy that understands the journey to truth in terms of the traveler's innate capacity. Anamnesis, maieutics, and elenchus each confirm that truth is not utterly foreign but is instead always within my possession or grasp. Other people, to the extent that they participate in my philosophical exploration, serve only to enable my capabilities or potential. They are not teachers to me. Nor would I need them, since I am always already in the neighborhood of truth. Emmanuel Levinas's description of the "face to face" encounter between people challenges the adequacy of this model. Another person is not simply a midwife who leads me to a recovery of truth that was always within me or within my domain. -

Anamnesis: Intertextual Memory and Alzheimer's Disease

genealogy Article Anamnesis: Intertextual Memory and Alzheimer’s Disease Kirstin Wagner Department of Literature, University of California-Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA; [email protected] Received: 2 May 2017; Accepted: 14 June 2017; Published: 16 June 2017 Abstract: This essay develops and performs a theory of intertextual memory; and uses this concept as a heuristic to re-conceptualize identity for people suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. This work emerges from three key sites of personal and cultural inquiry. At the center is my engagement with my matrilineal ancestry; which is haunted by the specter of memory loss: my mother’s mother (my Nanny) was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in 2002 when she was 73; and my mother was diagnosed with Early Onset Alzheimer’s in 2012 when she was 51. By telling stories about my mother and my Nanny which rely on intertextual memory; I hope to broaden the poetic space of remembering and to challenge the Western humanistic conception of identity as inherent; atomistic; and highly dependent on successful memory performance. Secondly; I examine the rhetorical discourse circulating Alzheimer’s disease in the popular cultural imaginary; where illness metaphors deleteriously situate the forgetting body within narratives of failure; fear; and loss of personhood. I argue that an intertextual approach to memory performance can help us reimagine Alzheimer’s patients outside the stigmatizing parameters of these broader cultural stories. Lastly; I draw on empirical research related to communication failure in AD in order to consider the ways caregivers might approach Alzheimer’s patients with the kind of linguistic and interactional flexibility subtended by an intertextual approach to identity; in order to forge improved relationships both with Alzheimer’s patients and with the disease itself. -

Liturgical Press Style Guide

STYLE GUIDE LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org STYLE GUIDE Seventh Edition Prepared by the Editorial and Production Staff of Liturgical Press LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design by Ann Blattner © 1980, 1983, 1990, 1997, 2001, 2004, 2008 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Printed in the United States of America. Contents Introduction 5 To the Author 5 Statement of Aims 5 1. Submitting a Manuscript 7 2. Formatting an Accepted Manuscript 8 3. Style 9 Quotations 10 Bibliography and Notes 11 Capitalization 14 Pronouns 22 Titles in English 22 Foreign-language Titles 22 Titles of Persons 24 Titles of Places and Structures 24 Citing Scripture References 25 Citing the Rule of Benedict 26 Citing Vatican Documents 27 Using Catechetical Material 27 Citing Papal, Curial, Conciliar, and Episcopal Documents 27 Citing the Summa Theologiae 28 Numbers 28 Plurals and Possessives 28 Bias-free Language 28 4. Process of Publication 30 Copyediting and Designing 30 Typesetting and Proofreading 30 Marketing and Advertising 33 3 5. Parts of the Work: Author Responsibilities 33 Front Matter 33 In the Text 35 Back Matter 36 Summary of Author Responsibilities 36 6. Notes for Translators 37 Additions to the Text 37 Rearrangement of the Text 37 Restoring Bibliographical References 37 Sample Permission Letter 38 Sample Release Form 39 4 Introduction To the Author Thank you for choosing Liturgical Press as the possible publisher of your manuscript. -

Narrative of the Institution by Roddy Hamilton

Narrative of the Institution by Roddy Hamilton The tradition which I handed on to you came to me from the Lord himself: that on the night of his arrest the Lord Jesus took bread, and after giving thanks to God broke it and said: ‘This is my body, which is for you; do this in memory of me.’ In the same way, he took the cup after supper, and said: ‘This cup is the new covenant sealed by my blood. Whenever you drink it, do this in memory of me.’ For every time you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the death of the Lord, until he comes. 1 Corinthians 11:23-26 These are the words that have echoed in the mouths and hearts of countless followers who have gathered round a table in community breaking bread and sharing wine with the Saviour. These are the words that have been whispered daringly in secret gatherings celebrating an illegal feast, breaking bread and sharing wine with the Saviour. These are the words that have had one set of believers dying on the rack whose cogs were turned by another set of believers for the sake of the same bread and wine and the same Saviour. These are the words that have slowed down the liturgy to become the ‘sacred moment’ as the community held its breath as bread was broken and wine poured in the name of the Saviour. But what of their place in the practice of our own tradition in contemporary times and how do they, or rather, how are they allowed to shape our understanding, experience and sharing of the Realm of God in broken bread and shared wine? A Traditional Understanding Marcus Borg1 talks about the pre-critical naiveté of accepting without question whatever has been handed on to us by the authority figures of our faith. -

Structure of the Mass Part 2

Semester Series: The Sacraments of the Church The Structure of the Mass Part TWO—The Liturgy of the Eucharist, and Dismissal Preparation of the Gifts As the Liturgy of the Eucharist begins we are seated and we perform the ritual of “preparing the gifts.” Bread and wine are brought forward to the altar, and prayers are prayed over these gifts in preparation for the calling forth of the Holy Spirit to transform them. As part of the preparation a small drop of water is placed into the wine. The water diffuses completely into the wine and cannot be separated back out, even after the wine is consecrated into the Precious Blood of Christ. This drop of water symbolizes us—we are united to the Precious Blood of Christ and cannot be separated from Him by any outward force. Romans 8 reminds us, “What will separate us from the love of Christ? Will anguish, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or the sword?” Once united to the saving love of Christ through His precious blood we are united to Him forever. The Anaphora—the Eucharistic Prayer —a Prayer of Grateful Thanks Once the gifts are prepared we are invited to stand and enter as a community into the Eucharistic Prayer. In imitation of the Jewish Passover, we begin this prayer by calling to mind how God has been present in our human history and experience. This prayer continues through the “Sanctus” or “Holy Holy” which is a biblical-based prayer coming directly from two parts of Scripture: • The song of praise of the angels, as recorded in Isaiah 6:3—One cried out to the other: “Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts! All the earth is filled with his glory!” • The greeting of Jesus during his triumphant entry into Jerusalem: Blessed is He who comes in the Name of the Lord, Hosanna in the highest!" (Matthew 21:9) The Anaphora-the Eucharistic Prayer – A Prayer of Epiclesis and Consecration Following the Sanctus we kneel out of respect for the Words of Consecration when the bread and wine will be transformed into the Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Christ.