The Institution Narrative, Eucharistic Prayers, and the Anglican Liturgical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F

Valparaiso University ValpoScholar Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers Institute of Liturgical Studies 2017 The weT ntieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Liturgy and Worship Commons Recommended Citation Baldovin, John F. S.J., "The wT entieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects" (2017). Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers. 126. http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers/126 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Liturgical Studies at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin, S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry Introduction Metanoiete. From the very first word of Jesus recorded in the Gospel of Mark reform and renewal have been an essential feature of Christian life and thought – just as they were critical to the message of the prophets of ancient Israel. The preaching of the Gospel presumes at least some openness to change, to acting differently and to thinking about things differently. This process has been repeated over and over again over the centuries. This insight forms the backbone of Gerhard Ladner’s classic work The Idea of Reform, where renovatio and reformatio are constants throughout Christian history.1 All of the great reform movements in the past twenty centuries have been in response to both changing cultural and societal circumstances (like the adaptation of Christianity north of the Alps) and the failure of Christians individually and communally to live up to the demands of the Gospel. -

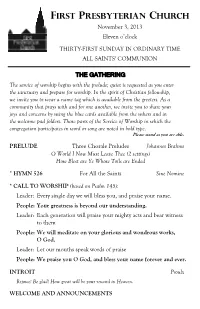

Ordinary 31C 11-3-2013 C&B.Pub

FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH November 3, 2013 Eleven o’clock THIRTY-FIRST SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME ALL SAINTS' COMMUNION THE GATHERING The service of worship begins with the prelude; quiet is requested as you enter the sanctuary and prepare for worship. In the spirit of Christian fellowship, we invite you to wear a name tag which is available from the greeters. As a community that prays with and for one another, we invite you to share your joys and concerns by using the blue cards available from the ushers and in the welcome pad folders. Those parts of the Service of Worship in which the congregation participates in word or song are noted in bold type. Please stand as you are able. PRELUDE Three Chorale Preludes Johannes Brahms O World I Now Must Leave Thee (2 settings) How Blest are Ye Whose Toils are Ended * HYMN 526 For All the Saints Sine Nomine * CALL TO WORSHIP (based on Psalm 145): Leader: Every single day we will bless you, and praise your name. People: Your greatness is beyond our understanding. Leader: Each generation will praise your mighty acts and bear witness to them People: We will meditate on your glorious and wondrous works, O God. Leader: Let our mouths speak words of praise People: We praise you O God, and bless your name forever and ever. INTROIT Proulx Rejoice! Be glad! How great will be your reward in Heaven. WELCOME AND ANNOUNCEMENTS CALL TO CONFESSION PRAYER OF CONFESSION Almighty God, we confess that we are unable to disentangle the good from the bad within us. -

Reverenómo Er Mar Angeica

Mass of Christian Burial A n d Rite of Committal ReverenÓMoer MarAngeica of the Annunciation, P. C. P. A . Abbess Emerita, Our Lady of the Angels Monastery FRidAy, APRiL 1, 2016 Moer MarAngeica April 20, 1923 – March 27, 2016 Professed January 2, 1947 Mass of Christian Burial a n d Rite of Committal Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament Hanceville, Alabama Table of Contents I. Requiem Mass 3 The Guidelines for Reception of Holy Communion can be found on the inside back cover of this booklet. II. Solemn Procession and Rite of Committal 15 Introductory Rites Processional Requiem aeternam CHOIR Giovanni Martini (1706-1784); arr. Rev. Scott A. Haynes, S.J.C. Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) from Requiem ANT: Requiem aeternam dona ei ANT: Rest eternal grant unto her, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat ei. O Lord, and may light perpetual shine upon her. PS 130: De profundis clamavit ad te PS 130: Out of the depths I have cried to Domine… thee, O Lord... (CanticaNOVA, pub.) Kyrie Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison. R. Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Collect P. We humbly beseech your mercy, O Lord, for your servant Mother Mary Angelica, that, having worked tirelessly for the spread of the Gospel, she may merit to enter into the rewards of the Kingdom. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. R. Amen. 3 The Liturgy of the Word First Reading Book of Wisdom 3:1-9 He accepted them as a holocaust. -

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I Prelude . Lighting of the Candles Greeting . Significance of the Day The Divine Service begins with the Hymn of Invocation (or the Processional Hymn, if there is a Procession), which helps set the tone and mood for the worship service, reminding us early on of God's great love through Jesus our Savior. Already, with the Prelude, the organist is directing our attention to the fact that in worship, "heaven touches earth," just as God's Word declares through the Virgin Mary in Luke 1:68: "Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, for He has visited and redeemed His people." Hymn of Invocation: CONFESSION AND ABSOLUTION Congregation shall stand The service continues as we invoke the name of the Triune God, put upon us by Jesus' command in our Baptism (Matthew 28:19) - the name in which we gather. St. Paul captures the eternal significance of our Baptism into Christ when he writes: "as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ" (Galatians 3:27). The sign of the cross may be made as a visible reminder of our Baptism. The congregation responds by saying, "Amen," which means "so let it be!” P In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. C Amen. The Exhortation is an invitation to confession. The inspired words of the Apostle John remind us that God is "faithful and just to forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness" (1 John 1:8-9). -

An Outline of a Eucharistic Prayer

An Outline of a Eucharistic Prayer The Eucharistic Prayers used in the Episcopal Church are based on an ancient outline of prayer found in something called “The Text of Hippolytus.” Though the actual words of the eucharistic prayer may vary, every eucharistic prayer contains the same elements. Presider: The Lord be with you. The opening versicles and responses. Here the People: And also with you. presider greets the congregation, reminds them of the joyous purpose that brings us to the table, Presider: Lift up your hearts. and then asks their permission to offer the People: We lift them up to the Lord. eucharistic prayer on their behalf. Known as the “Sursum Corda,” meaning “Lift up your hearts.” Presider: Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. People: It is right to give God thanks and praise. Presider: Good morning, Lord. We are Eucharistic prayers generally include a short your people, gathered at your table to give your recitation of salvation history. Here, the prayer thanks and praise. Thank you for always gives thanks for the ways God reveals God’s self, revealing yourself: in Creation; in your people, fully and completely in Jesus, the Word made gathered and sent; in your Word spoken through flesh. While sometimes the eucharistic prayer the Scriptures; and above all in the Word made may emphasize the offering made on the cross, flesh, Jesus, your Son. You sent him to be this one emphasizes the incarnation…God incarnate from the Virgin Mary, to be the Savior becoming human in Jesus Christ. and Redeemer of the world. -

Narrative of the Institution by Roddy Hamilton

Narrative of the Institution by Roddy Hamilton The tradition which I handed on to you came to me from the Lord himself: that on the night of his arrest the Lord Jesus took bread, and after giving thanks to God broke it and said: ‘This is my body, which is for you; do this in memory of me.’ In the same way, he took the cup after supper, and said: ‘This cup is the new covenant sealed by my blood. Whenever you drink it, do this in memory of me.’ For every time you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the death of the Lord, until he comes. 1 Corinthians 11:23-26 These are the words that have echoed in the mouths and hearts of countless followers who have gathered round a table in community breaking bread and sharing wine with the Saviour. These are the words that have been whispered daringly in secret gatherings celebrating an illegal feast, breaking bread and sharing wine with the Saviour. These are the words that have had one set of believers dying on the rack whose cogs were turned by another set of believers for the sake of the same bread and wine and the same Saviour. These are the words that have slowed down the liturgy to become the ‘sacred moment’ as the community held its breath as bread was broken and wine poured in the name of the Saviour. But what of their place in the practice of our own tradition in contemporary times and how do they, or rather, how are they allowed to shape our understanding, experience and sharing of the Realm of God in broken bread and shared wine? A Traditional Understanding Marcus Borg1 talks about the pre-critical naiveté of accepting without question whatever has been handed on to us by the authority figures of our faith. -

Aspects of Epiclesis in the Roman Mass

Aspects of Epiclesis in the Roman Mass For generations in the Roman Catholic Church the so-called Roman Rite held almost universal sway - probably from its beginnings in the early centuries and certainly through to the Second Vatican Council of the nineteen sixties. It was not that there were no other forms: the Mozarabic, the Gallican, the Ambrosian for example, some of which have managed tenuously to survive till our day. But when Latin eventually replaced Greek as the liturgical language of the Church in Rome, and a strong conservatism prevailed, so the form of the mass used in Rome gradually took precedence over other rites in the Western Church This might seem an odd quirk of history. The old Roman rite is markedly different from the ancient liturgies of the east, and even in many respects from the other western rites we have mentioned. Whereas the latter retained some of the elements of the Eastern tradition, the Church in Rome seems to have deprived itself of much of that richness. No doubt this was partly due to the adoption of Latin, with its concise precision of expression, in contrast with the greater profuseness and poetic style of the Greek liturgical language. But the differences also marked a growing divergence in theological understanding. Such differences need not, however, make for insuperable barriers now between east and west, despite the polemics of centuries. The recent liturgical and ecumenical movements have given rise to fresh insights and some change of climate. It is actually possible now to look dispassionately at the old Roman rite and to find, not surprisingly, that many of the so-called eastern emphases are not in fact wholly absent. -

Robert F. Taft, SJ Mass Without the Consecration? the Historic Agreement on the Eucharist Between the Catholic Church and the As

R.F. Taft SJ / Addai & Mari Robert F. Taft, SJ Mass Without the Consecration? The Historic Agreement on the Eucharist Between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East Promulgated 26 October 20011 My deliberately provocative title, “Mass Without the Consecration?,” I owe to a high-ranking Catholic prelate who, upon hearing of the epoch-making decree of the Holy See recognizing the validity of the eucharistic sacrifice celebrated according to the original redaction of the Anaphora of Addai and Mari—i.e., without the Words of Institution—exclaimed in perplexity: “But how can there be Mass without the consecration?” The answer, of course, is that there cannot be. But that does not solve the problem; it just shifts the question to “What, then, is the consecration, if not the traditional Institution Narrative which all three Synoptic Gospels2 and 1 Cor 11:23-26 attribute to Jesus?” The 26 October 2001 Agreement One of the basic tasks of the Catholic theologian is to provide the theological underpinnings to explain and justify authentic decisions of the Supreme Magisterium. That is my aim here. For the historic agreement on the eucharist between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East is surely one such authentic decision, approved by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, the Congregation for the Oriental Churches, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and Pope John Paul II himself. This decision tells Catholics who fulfill the stated conditions and receive Holy Communion at an Assyrian eucharist using the Anaphora of Addai and Mari, that they are receiving the one true Body and Blood of Christ, as at a Catholic eucharist. -

Thb Reformation in Worship: the Ministry of the Sacraments

THE REFORMATION IN WORSHIP-THE SACRAMENTS 100 THB REFORMATION IN WORSHIP: THE MINISTRY OF THE SACRAMENTS. By the Rev. Canon J. R. S. TAYLOR, M.A. Principal of Wycliffe Hall, Oxford. "'rHE title of my paper is, "The Reformation in Worship: the 1 Ministry of the Sacraments." The terms of reference are given in the third cause for thanksgiving commended by the promoters of this centenary celebration, namely " The Reformation by its appeal to the Scriptures led to the recognition of more spiritual conceptions of the Church and Sacraments, to the purification of worship, and to renewed emphasis on the ministry of the word." The three phrases pertinent to this paper are : " The appeal to the Scriptures/' " more spiritual conceptions ofthe Sacraments,"" the purification ofworship., I will try to follow the scheme there suggested. I. The Appeal to the Scriptures. Why did the Reformers make this appeal ? They were driven to it by force of circumstances. Luther's conscience was offended by the growing scandal and menace of the system of purchasing pardons and dispensations. He appealed to the authorities of the Church, believing that when the full extent of the evil was made known they would initiate reform, but he was disappointed. The power of vested interests was too strong. What was he to do-to silence his conscience and let the matter rest ? His conscience refused to be silenced. It had been quickened by a new knowledge of God, brought to him in the New Testament, and the voice of God which had spoken in scripture was authoritative. -

To Our Roman Catholic Church

W To E L Our C Roman “And so I say to you, you are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church...” Matthew 16:18 O M Catholic E Church A Quick and Simple Guide to Basic Catholic Teachings and Rituals Introduction Internet Sites and References Welcome to our Roman Catholic Church. Th is booklet was written as a short yet helpful Internet Sites guide to basic teachings and rituals of the Catholic Church. May it welcome and encourage you to join with us as we celebrate our Faith. Based upon Roman Missal Formational Materials provided by the Secretariat for the Liturgy of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2010. (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops site) <http://www.usccb.org/romanmissal/> A PDF of this booklet may be downloaded and reproduced Global Catholic Network (Eternal Word Television Network) <http://www.ewtn.com> for nonprofit informational use, at www.ollmtarlington.org New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia (New Advent is a Catholic reference site maintained by a Catholic layman) <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen> By Nancy C. Hefele Th e New American Bible, Revised Edition (At the United States Conference of Catholic Nihil obstat Rev. T. Kevin Corcoran Bishops site) <http://www.usccb.org/bible/index.cfm> Vice Chancellor, Diocese of Paterson Imprimatur Most Reverend Arthur J. Serratelli, S.T.D., S.S.L., D.D Books Bishop of Paterson Canon Law Society of America. Code of Canon Law, Latin – English Edition (New English Edition). Washington, D.C.: Canon Law Society of America, 1983. Paterson Diocesan Center United States Catholic Conference, Inc. -

Rev. Lilienthal 14 December 2018 I Want to Express Appreciation That

ANSWERING A FEW QUESTIONS ABOUT WORSHIP Rev. Lilienthal 14 December 2018 I want to express appreciation that these questions were actually brought to me, rather than allowed to fester and cause disruption in the Church. St. Paul wrote to St. Timothy, “Remind [the people] of these things, and charge them before God not to quarrel about words, which does no good, but only ruins the hearers…. Have nothing to do with foolish, ignorant controversies; you know that they breed quarrels” (2 Tim. 2:14, 23). When we refer to things that are a matter of choice or tradition, things neither commanded nor forbidden in Scripture, we call these things “adiaphora” (AH-dee-ah-for-ah). The form of worship (or liturgy) as well as the hymns, the rites and ceremonies, the vestments and paraments and church decorations and furniture, are all just such adiaphora. However, using the term “adiaphora” does not mean we should be indifferent about such things. Calling a thing “adiaphoron” is the beginning of the conversation. Once a thing is determined to be adiaphoron, it is the responsibility of the church to decide the best way to do a thing, so that God’s Word and Sacraments may be given central importance in communicating Christ and his grace to the people of God. For this purpose, the office of the pastoral ministry is put in place, to lead the congregation by preaching the Word and administering the Sacraments. When questions are asked about “why” a thing is done a certain way, it is important for the Pastor to be able to answer that question. -

“The Great Thanksgiving,” Which Remind Us of What God Did for Us in Jesus

The words we say in preparation are often called “The Great Thanksgiving,” which remind us of what God did for us in Jesus. It begins with a call and response called the “Sursum Corda” from the Latin words for “Lift up your hearts.” It is an ancient part of the liturgy since the very early centuries of the Church, and a remnant of an early Jewish call to worship. These words remind us that when we observe communion, we are to be thankful and joyful. The Lord be with you. And also with you. Lift up your hearts. We lift them up to the Lord. Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. It is right to give our thanks and praise. The next section is spoken by the clergy and is called “The Proper Preface.” It has optional words that connect to the particular day or season of the church year. We will notice that by the time this communion liturgy is over, it will have covered all three parts of the Trinity. This first section focuses on God the Father: It is right, and a good and joyful thing, always and everywhere to give thanks to you, Father Almighty, creator of heaven and earth. The congregation then recites “The Sanctus,” from the Latin word for “Holy.” It comes from two Scripture texts: 1) Isaiah’s vision of heaven in Isaiah 6:3: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory,” and 2) Matthew 21:9, in which Jesus enters Jerusalem and the people shout, “Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest heaven!” These words remind us that through communion, we enter a holy experience with Jesus.