The Recognition of the Addai and Mari Anaphora by the Catholic Church in 2001: the Theological Contribution and the Main Arguments of Archimandrite Robert Taft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F

Valparaiso University ValpoScholar Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers Institute of Liturgical Studies 2017 The weT ntieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Liturgy and Worship Commons Recommended Citation Baldovin, John F. S.J., "The wT entieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects" (2017). Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers. 126. http://scholar.valpo.edu/ils_papers/126 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Liturgical Studies at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute of Liturgical Studies Occasional Papers by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Twentieth Century Reform of the Liturgy: Outcomes and Prospects John F. Baldovin, S.J. Boston College School of Theology & Ministry Introduction Metanoiete. From the very first word of Jesus recorded in the Gospel of Mark reform and renewal have been an essential feature of Christian life and thought – just as they were critical to the message of the prophets of ancient Israel. The preaching of the Gospel presumes at least some openness to change, to acting differently and to thinking about things differently. This process has been repeated over and over again over the centuries. This insight forms the backbone of Gerhard Ladner’s classic work The Idea of Reform, where renovatio and reformatio are constants throughout Christian history.1 All of the great reform movements in the past twenty centuries have been in response to both changing cultural and societal circumstances (like the adaptation of Christianity north of the Alps) and the failure of Christians individually and communally to live up to the demands of the Gospel. -

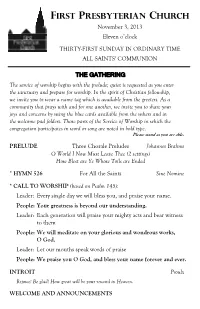

Ordinary 31C 11-3-2013 C&B.Pub

FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH November 3, 2013 Eleven o’clock THIRTY-FIRST SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME ALL SAINTS' COMMUNION THE GATHERING The service of worship begins with the prelude; quiet is requested as you enter the sanctuary and prepare for worship. In the spirit of Christian fellowship, we invite you to wear a name tag which is available from the greeters. As a community that prays with and for one another, we invite you to share your joys and concerns by using the blue cards available from the ushers and in the welcome pad folders. Those parts of the Service of Worship in which the congregation participates in word or song are noted in bold type. Please stand as you are able. PRELUDE Three Chorale Preludes Johannes Brahms O World I Now Must Leave Thee (2 settings) How Blest are Ye Whose Toils are Ended * HYMN 526 For All the Saints Sine Nomine * CALL TO WORSHIP (based on Psalm 145): Leader: Every single day we will bless you, and praise your name. People: Your greatness is beyond our understanding. Leader: Each generation will praise your mighty acts and bear witness to them People: We will meditate on your glorious and wondrous works, O God. Leader: Let our mouths speak words of praise People: We praise you O God, and bless your name forever and ever. INTROIT Proulx Rejoice! Be glad! How great will be your reward in Heaven. WELCOME AND ANNOUNCEMENTS CALL TO CONFESSION PRAYER OF CONFESSION Almighty God, we confess that we are unable to disentangle the good from the bad within us. -

Reverenómo Er Mar Angeica

Mass of Christian Burial A n d Rite of Committal ReverenÓMoer MarAngeica of the Annunciation, P. C. P. A . Abbess Emerita, Our Lady of the Angels Monastery FRidAy, APRiL 1, 2016 Moer MarAngeica April 20, 1923 – March 27, 2016 Professed January 2, 1947 Mass of Christian Burial a n d Rite of Committal Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament Hanceville, Alabama Table of Contents I. Requiem Mass 3 The Guidelines for Reception of Holy Communion can be found on the inside back cover of this booklet. II. Solemn Procession and Rite of Committal 15 Introductory Rites Processional Requiem aeternam CHOIR Giovanni Martini (1706-1784); arr. Rev. Scott A. Haynes, S.J.C. Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) from Requiem ANT: Requiem aeternam dona ei ANT: Rest eternal grant unto her, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat ei. O Lord, and may light perpetual shine upon her. PS 130: De profundis clamavit ad te PS 130: Out of the depths I have cried to Domine… thee, O Lord... (CanticaNOVA, pub.) Kyrie Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison. R. Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison. R. Kyrie eleison. Collect P. We humbly beseech your mercy, O Lord, for your servant Mother Mary Angelica, that, having worked tirelessly for the spread of the Gospel, she may merit to enter into the rewards of the Kingdom. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. R. Amen. 3 The Liturgy of the Word First Reading Book of Wisdom 3:1-9 He accepted them as a holocaust. -

The Sacraments of the Assyrian Church of the East

1 The Sacraments of the Assyrian Church of the East The Sacraments of the Assyrian Church of the East Most Rev. Mar Awa Royel Bishop of California First and foremost, in the Western theological jargon the word ‘sacrament’ is spoken of. It comes from the Latin sacramentum, which originally denoted a sacred oath; in general, it was the oath that a Roman soldier gave to Caesar upon the soldier’s inscription in the Roman army.1 It had, therefore, a sacred tone to it—one solemnly vowed to uphold and defend Caesar and the Roman Empire. In the Greek-speaking East, the word for sacrament is mysterion, and in its origins, it refers to the sacred, secret Mystery Cults of the Greek religion (the secret rites of ‘Bacchius’ come immediately to mind). Only those inducted into these sacred rites would be able to know the ‘mystery’ and what it entails. The Assyrian Church of the East makes use of the term rāzā to denote ‘sacrament’ or ‘mystery.’ It comes from the Middle Persian (Pahlavi) term ‘raz,’ meaning something concealed; hidden.2 It must have made its way into Assyrian and then Aramaic sometime in the 4th or 5th century B.C.3 A rāzā, or sacrament, is essentially a mystery through which God acts to impart to us his grace, but we don’t know how this happens. However, we do feel the 1 The first Christian writer to use the word ‘sacrament’ was Tertullian (3rd century), who explained that through Baptism we are ‘enlisted’ into the army of Christ. -

Divinity School 2013–2014

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut Divinity School 2013–2014 Divinity School Divinity 2013–2014 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 109 Number 3 June 20, 2013 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 109 Number 3 June 20, 2013 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, or PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and covered veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to the Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 203.432.0849. -

Mass Moment: Part 23 the EUCHARISTIC PRAYER (Anaphora)

5 Mass Moment: Part 23 THE EUCHARISTIC PRAYER (Anaphora). After the acclamation (the Holy, Holy, Holy), the congregation kneels while the priest, standing with arms outstretched, offers up the prayer (Anaphora) directly addressed to God the Father. This indicates even more clearly that the whole body directs its prayer to the Father only through its head, Christ. The Anaphora is the most solemn part of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, during which the offerings of bread and wine are consecrated as the body and blood of Christ. There are four main Eucharistic Prayers, also called Canon (I, II, III, IV). However, there are also four for Masses for Various Needs (I, II, III, IV) and two for Reconciliation (I, II). They are purely biblical in theology and in language, they possess a rich overtone from its Latin origins. It is important to note the elements that are central and uniform all through the various Eucharistic Prayers: the praise of God, thanksgiving, invocation of the Holy Spirit (also known as Epiclesis), the that is the up Christ our oblation to the Father through the Holy Spirit, then the doxology The first Canon is the longest and it includes the special communicates offering in union with the whole Church. The second Canon is the shortest and often used for daily Masses. It is said to be the oldest of the four Anaphoras by St. Hippolytus around 215 A.D. It has its own preface, but it also adapts and uses other prefaces too. The third Eucharistic Prayer is said to be based on the ancient Alexandrian, Byzantine, and Maronite Anaphoras, rich in sacrificial theology. -

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I

Explanation of the Lutheran Liturgy Based on LSB Divine Service I Prelude . Lighting of the Candles Greeting . Significance of the Day The Divine Service begins with the Hymn of Invocation (or the Processional Hymn, if there is a Procession), which helps set the tone and mood for the worship service, reminding us early on of God's great love through Jesus our Savior. Already, with the Prelude, the organist is directing our attention to the fact that in worship, "heaven touches earth," just as God's Word declares through the Virgin Mary in Luke 1:68: "Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, for He has visited and redeemed His people." Hymn of Invocation: CONFESSION AND ABSOLUTION Congregation shall stand The service continues as we invoke the name of the Triune God, put upon us by Jesus' command in our Baptism (Matthew 28:19) - the name in which we gather. St. Paul captures the eternal significance of our Baptism into Christ when he writes: "as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ" (Galatians 3:27). The sign of the cross may be made as a visible reminder of our Baptism. The congregation responds by saying, "Amen," which means "so let it be!” P In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. C Amen. The Exhortation is an invitation to confession. The inspired words of the Apostle John remind us that God is "faithful and just to forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness" (1 John 1:8-9). -

An Outline of a Eucharistic Prayer

An Outline of a Eucharistic Prayer The Eucharistic Prayers used in the Episcopal Church are based on an ancient outline of prayer found in something called “The Text of Hippolytus.” Though the actual words of the eucharistic prayer may vary, every eucharistic prayer contains the same elements. Presider: The Lord be with you. The opening versicles and responses. Here the People: And also with you. presider greets the congregation, reminds them of the joyous purpose that brings us to the table, Presider: Lift up your hearts. and then asks their permission to offer the People: We lift them up to the Lord. eucharistic prayer on their behalf. Known as the “Sursum Corda,” meaning “Lift up your hearts.” Presider: Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. People: It is right to give God thanks and praise. Presider: Good morning, Lord. We are Eucharistic prayers generally include a short your people, gathered at your table to give your recitation of salvation history. Here, the prayer thanks and praise. Thank you for always gives thanks for the ways God reveals God’s self, revealing yourself: in Creation; in your people, fully and completely in Jesus, the Word made gathered and sent; in your Word spoken through flesh. While sometimes the eucharistic prayer the Scriptures; and above all in the Word made may emphasize the offering made on the cross, flesh, Jesus, your Son. You sent him to be this one emphasizes the incarnation…God incarnate from the Virgin Mary, to be the Savior becoming human in Jesus Christ. and Redeemer of the world. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA the Missa Chrismatis: a Liturgical Theology a DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the S

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Missa Chrismatis: A Liturgical Theology A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Sacred Theology © Copyright All rights reserved By Seth Nater Arwo-Doqu Washington, DC 2013 The Missa Chrismatis: A Liturgical Theology Seth Nater Arwo-Doqu, S.T.D. Director: Kevin W. Irwin, S.T.D. The Missa Chrismatis (“Chrism Mass”), the annual ritual Mass that celebrates the blessing of the sacramental oils ordinarily held on Holy Thursday morning, was revised in accordance with the decrees of Vatican II and promulgated by the authority of Pope Paul VI and inserted in the newly promulgated Missale Romanum in 1970. Also revised, in tandem with the Missa Chrismatis, is the Ordo Benedicendi Oleum Catechumenorum et Infirmorum et Conficiendi Chrisma (Ordo), and promulgated editio typica on December 3, 1970. Based upon the scholarly consensus of liturgical theologians that liturgical events are acts of theology, this study seeks to delineate the liturgical theology of the Missa Chrismatis by applying the method of liturgical theology proposed by Kevin Irwin in Context and Text. A critical study of the prayers, both ancient and new, for the consecration of Chrism and the blessing of the oils of the sick and of catechumens reveals rich theological data. In general it can be said that the fundamental theological principle of the Missa Chrismatis is initiatory and consecratory. The study delves into the history of the chrismal liturgy from its earliest foundations as a Mass in the Gelasianum Vetus, including the chrismal consecration and blessing of the oils during the missa in cena domini, recorded in the Hadrianum, Ordines Romani, and Pontificales Romani of the Middle Ages, through the reforms of 1955-56, 1965 and, finally, 1970. -

The Anaphora of the Apostles: Implications of the Mar Ε§Αύα Text Emmanuel J

THE ANAPHORA OF THE APOSTLES: IMPLICATIONS OF THE MAR Ε§ΑΎΑ TEXT EMMANUEL J. CUTRONE Quincy College, Illinois ike Russia, the East Syrian anaphora of the apostles Addai and Mari IJ qualifies as both mystery and enigma. The research done on the many mysteries of this third-eentury East Syrian anaphora usually clarifies all too sharply the many enigmas that still remain.1 Unlike other anaphoras which share its antiquity—Hippolytus, Apostolic Constitutions 8, Serapion, or the earlier witness of Justin—Addai and Mari is not a prototype academic exercise of a typical Eucharistie prayer.2 This anaphora was, and continues to be, an actual prayer of a worshiping community. Bouyer feels that "everything leads us to believe that this prayer is the most ancient christian eucharistie com- 1 Here is a listing of the major studies done on the Anaphora of the Apostles Addai and Mari: Bernard Botte, "L'Anaphore chaldéenne des apôtres," Orientalin Christiana periodica 15 (1949) 259-76; Β. Botte, "L'Epielèse dans les liturgies syriennes orientales," Sacris erudiri 6 (1954) 48-72; B. Botte, "Problème de l'anaphore syrienne des apôtres Addai et Mari," L'Orient syrien 10 (1965) 89-106; Louis Bouyer, Eucharist: Theology and Spirituality of the Eucharistie Prayer, tr. Charles Quinn (Notre Dame, Ind., 1966) pp. 146-57; Hieronymus Engberding, "Zum anaphorischen Fürbittgebet des ostsyrischen Liturgie Addaj und Mar(j)," Oriens christianus 41 (1957) 102-24; S. H. Jammo, "Gabriel Qatraya et son commentaire sur la liturgie chaldéenne," Orientalia Christiana periodica 32 (1966) 39-52; William F. Macomber, "The Oldest Known Text of the Anaphora of the Apostles Addai and Mari," ibid. -

Sentential Negativity and Polarity-Sensitive Anaphora a Hyperintensional Account

Sentential negativity and polarity-sensitive anaphora A hyperintensional account Lisa Hofmann University of California Santa Cruz 1 Introduction This paper is concerned with an asymmetry between positive and negative sen- tences in discourse.1 The licensing of certain propositional anaphora is contin- gent on the polarity of their antecedent clause. I call them Polarity-Sensitive Anaphora (PSAs). Among these are polar additives (Klima (1964)) and polarity particles (Farkas and Bruce (2010); Roelofsen and Farkas (2015)). (1) Polar additives (2) Agreement with polarity particles a. Mary slept. a. Mary slept. (i) So did Dalia. (i) Yes, she slept. (ii) #Neither did Dalia. (ii) #No, she slept. b. Mary didn’t sleep. b. Mary didn’t sleep. (i) #So did Dalia. (i) Yes, she didn’t sleep. (ii) Neither did Dalia. (ii) No, she didn’t sleep. Polar additives are polarity-sensitive in their licensing: Positive polar ad- ditives with so are available with a positive antecedent (1-a), but not with a negative one (1-b), whereas neither shows the opposite pattern. Polarity parti- cles (PolPs) are polarity-sensitive in their interpretation. In a positive context (2-a), only yes, but not no can be used to agree with the antecedent. In the negative context, this contrast is neutralized (Ginzburg and Sag (2000); Roelof- sen and Farkas (2015)) and either polarity particle can be used to agree. These asymmetries lead me to two questions: 1. How can the polarity-sensitivity of PSAs be accounted for? 2. What renders a sentence positive/negative for the purposes of discourse and how might that be captured theoretically? 1. -

Copy of Holy Eucharist

HOLY EUCHARIST WHEN DID JESUS CHRIST INSTITUTE THE EUCHARIST? Jesus instituted the Eucharist on Holy Thursday “the night on which he was betrayed” (1 Corinthians 11:23), as he celebrated the Last Supper with his apostles. WHAT DOES THE EUCHARIST REPRESENT IN THE LIFE OF THE CHURCH? It is the source and summit of all Christian life. In the Eucharist, the sanctifying action of God in our regard and our worship of him reach their high point. It contains the whole spiritual good of the Church, Christ himself, our Pasch. Communion with divine life and the unity of the People of God are both expressed and effected by the Eucharist. Through the Eucharistic celebration we are united already with the liturgy of heaven and we have a foretaste of eternal life. WHAT ARE THE NAMES FOR THIS SACRAMENT? The unfathomable richness of this sacrament is expressed in different names which evoke its various aspects. The most common names are: the Eucharist, Holy Mass, the Lord’s Supper, the Breaking of the Bread, the Eucharistic Celebration, the Memorial of the passion, death and Resurrection of the Lord, the Holy Sacrifice, the Holy and Divine Liturgy, the Sacred Mysteries, the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar, and Holy Communion. HOW IS THE CELEBRATION OF THE HOLY EUCHARIST CARRIED OUT? The Eucharist unfolds in two great parts which together form one, single act of worship. The Liturgy of the Word involves proclaiming and listening to the Word of God. The Liturgy of the Eucharist includes the presentation of the bread and wine, the prayer or the anaphora containing the words of consecration, and communion.