Dirk Campbell's Origins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riflessioni Sul Potere Dell'im- Maginazione E Dei Suoi Limiti 'Ocos

_ Anno X N. 97 | Settembre 2021 | ISSN 2431 - 6739 Cannes 2021: riflessioni sul potere dell’im- ‘Ocos maginazione e dei suoi limiti Nasciamo e ci mettiamo ad ardere, finché il fumo dilegua come fumo. Il festival di Cannes si Non sono presenti in queste opere rappresen- Yehuda Amichai - Poesie è svolto nel mese dello tazioni distopiche sul virus, cioè non sono a cura di Ariel Rathaus scorso Luglio, fuori dal emerse ad esempio riflessioni sulla ripresa Milano, Crocetti, 1993, 2001 suo tempo canonico. La economica dopo lo shock della crisi sanitaria. volontà dell’organizza- E sono pochissime le scene cinematografiche zione è stata quella di in cui la trama del film abbia fatto vedere ma- È un paesaggio che mostrare la capacità di scherine coprire il viso dei personaggi. È la ri- non ha niente a che ve- saper realizzare un prova che nel cinema contemporaneo si sia dere con La hora de los grande evento di spet- sviluppata una crescente difficoltà per molti hornos (1968), il docu- tacolo in piena pan- cineasti di saper trattare il tema identitario in Àngel Quintana mentario di Fernando demia. Con il deside- un mondo così complesso. Solanas e Octavio Ge- rio di voler dimostrare che la cultura si può A Chiara, il film di Jonas Carpignano, si rac- tino sul neocoloniali- salvare nonostante tutto. Molti dei film pre- conta dell’esperienza di una ragazza che, do- smo e sulle rivoluzioni sentati a Cannes si trovavano da più di un an- po la scomparsa del padre, vive una nuova Natalino Piras della martoriata Ame- no bloccati a causa della chiusura delle sale ci- condizione che la obbliga a interrogarsi sulla rica Latina, sul finire degli anni Sessanta del nematografiche, altre pellicole sono state sua reale identità e, conseguentemente, su co- secolo scorso. -

The History and Revival of the Meråker Clarinet

MOT 2016 ombrukket 4.qxp_Layout 1 03.02.2017 15.49 Side 81 “I saw it on the telly” – The history and revival of the Meråker clarinet Bjørn Aksdal Introduction One of the most popular TV-programmes in Norway over the last 40 years has been the weekly magazine “Norge Rundt” (Around Norway).1 Each half-hour programme contains reports from different parts of Norway, made locally by the regional offices of NRK, the Norwegian state broad- casting company. In 1981, a report was presented from the parish of Meråker in the county of Nord-Trøndelag, where a 69-year old local fiddler by the name of Harald Gilland (1912–1992), played a whistle or flute-like instrument, which he had made himself. He called the instrument a “fløit” (flute, whistle), but it sounded more like a kind of home-made clarinet. When the instrument was pictured in close-up, it was possible to see that a single reed was fastened to the blown end (mouth-piece). This made me curious, because there was no information about any other corresponding instrument in living tradition in Norway. Shortly afterwards, I contacted Harald Gilland, and we arranged that I should come to Meråker a few days later and pay him a visit. The parish of Meråker has around 2900 inhabitants and is situated ca. 80 km northeast of Trondheim, close to the Swedish border and the county of Jamtlandia. Harald Gilland was born in a place called Stordalen in the 1. The first programme in this series was sent on October 2nd 1976. -

Marco De Referencia Para El Área De Aprendizaje De Desarrollo Global

Marco de referencia para el área de aprendizaje de Desarrollo Global Marco de referencia para el área de aprendizaje de desarrollo global en el marco de una Educación para el desarrollo sostenible 2ª edición actualizada y ampliada, 2016 Una contribución al programa de acción internacional “Educación para el desarrollo sostenible” Confeccionado y editado por: Jörg-Robert Schreiber y Hannes Siege Resultado del proyecto en conjunto con la Conferencia de Ministros de Educación y Ciencia (KMK, por sus siglas en alemán) y el Ministerio Federal de Cooperación Económica y Desarrollo (BMZ, por sus siglas en alemán) 2004–2015, Bonn Por encargo de: La Conferencia Permanente de los Ministros de Cultura de los Estados Federados de la República Federal de Alemania www.kmk.org, Correo electrónico: [email protected] Taubenstraße 10, D-10117 Berlin Código postal 11 03 42, D-10833 Berlín Tel. +49 (0) 30 254 18-499 Fax +49 (0) 30 254 18-450 Ministerio Federal de Cooperación Económica y Desarrollo www.bmz.de, Correo electrónico: [email protected] Sede Bonn Código postal 12 03 22, D-53045 Bonn Tel. +49 (0) 228 99 535-0 Fax +49 (0) 228 99 535-2500 Sede Berlin Stresemannstraße 94, D-10963 Berlin Tel. +49 (0) 30 18 535-0 Fax +49 (0) 30 18 535-2501 Publicado por: ENGAGEMENT GLOBAL gGmbH Servicio para iniciativas de desarrollo Tulpenfeld 7, D-53113 Bonn Tel. +49 (0) 228 20717-0 Fax +49 (0) 228 20717-150 www.engagement-global.de Correo electrónico: [email protected] Redacción: Jörg Peter Müller Diseño: zweiband.media, Berlín Implementación tecnológica: -

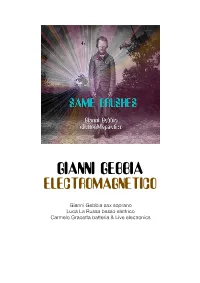

Elettromagnetico 3 Pres It. Copia

GIANNI GEBBIA ELECTROMAGNETICO Gianni Gebbia sax soprano Luca La Russa basso elettrico Carmelo Graceffa batteria & Live electronics Il noto sassofonista e compositore siciliano Gianni Gebbia ha creato questo nuovo trio elettrico nel 2016 con lo scopo di concentrarsi sulle proprie composizioni e melodie sviluppate in un lunghissimo arco di tempo dai primi anni 80 ad oggi attraversando le esperienze musicali più disparate : dal folk alla world music, dai gruppi prog anni 70 all’improvvisazione radicale al jazz contemporaneo. In elettromagnetico vi è una speciale attenzione sui moduli ipnotici e ripetitivi accanto allo sviluppo di melodie derivanti dalla tradizione musicale delle isole del mediterraneo ma anche elementi influenze come i Magma, Wayne Shorter, Nucleus, Deerhoof. Lo accompagnano in questa ricerca il bassista Luca La Russa ed il batterista Carmelo Graceffa due giovani e solidi musicisti che supportano e sviluppano le idee del saxofonista con grande intensità. Gianni Gebbia utilizza la respirazione circolare della quale è considerato uno dei massimi esploratori come metodo elettivo per creare questo climax magnetico ed ipnotico che ci porta in un viaggio che parte dai cantori ignoti delle strade di Palermo ai maestri sardi delle launeddas sino alle sonorità di uno Steve Lacy.Nel Luglio 2016 hanno inciso il loro primo album per l’etichetta objet-a dal titolo “ Same Brushes “. Il Trio elettromagnetico ha già compiuto un primo tour europeo ed ha partecipato al rock festival Pas de Trai 2016, Levanzo Community Fest e al prestigioso Festiwall 2016 a Ragusa una delle massime rassegne al mondo di street painting. A settembre del 2016 Il brano Lynx è stato inserito come download of the day dalla rivista online Allaboutjazz.com/usa raggiungendo migliaia di ascolti. -

Sconfinando a Sarzana

Supplemento alla Collana Smeraldo Autorizzazione Tribunale di Genova n. 40 del 31-10-1985 bimestrale Anno 2 n° 2 settembre-ottobre 2003 8,00 con CD L’inserto cd: Tuscae Gentes Sconfinando a Sarzana Festival dei Popoli Mediterranei di Bisceglie Cecil Sharp House - Inghilterra Gabriel Yacoub - Francia Førde Festival - Norvegia Andrea Parodi ex Tazenda - Italia Tanz&FolkFest - Germania Phønix - Danimarca Editoriale di LORIS BÖHM uesto è il secondo editoriale, un editoriale un po’ in arrivo altre entusia- anomalo e insolitamente lungo in cui parleremo smanti novità, come la Qcome al solito dei nostri progetti e delle nostre possibilità di acquistare idee, le quali non devono necessariamente collimare rivista + compact disc, con altre riviste del settore... anzi! Insomma saremo o come la presentazione www.etnobazar.it/folkmusic produttivi come nostra abitudine, e per dimostrare di gruppi autoprodotti di essere in sintonia con le altre testate (che vogliono emergenti, o come la SETTEMBRE-OTTOBRE 2003 produrre) e in concorrenza con nessuno al mondo, dal filosofia di relazionare N° 2 prossimo numero inizieremo una rubrica riservata con major discografiche proprio a descrivere senza pregiudizio le altre testate e produttori radiotele- SOMMARIO giornalistiche del settore; un’idea cui nessuno finora visivi, che sono la vera aveva mai pensato; vogliamo rendere al lettore un spina dorsale per il fu- Inserto CD: Tuscae Gentes servizio utile esclusivo. Qualche opinionista in vena turo della musica che ......................3 di polemiche ha frainteso il nostro editoriale prece- amiamo e per tutti co- La Cecil Sharp House dente. È normale fare dichiarazioni un po’ bellicose al loro che ci lavorano. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

ARC Music CATALOGUE

WELCOME TO THE ARC Music CATALOGUE Welcome to the latest ARC Music catalogue. Here you will find possibly the finest and largest collection of world & folk music and other related genres in the world. Covering music from Africa to Ireland, from Tahiti to Iceland, from Tierra del Fuego to Yakutia and from Tango, Salsa and Merengue to world music fusion and crossovers to mainstream - our repertoire is huge. Our label was established in 1976 and since then we have built up a considerable library of recordings which document the indig- enous lifestyles and traditions of cultures and peoples from all over the world. We strive to supply you with interesting and pleasing recordings of the highest quality and at the same time providing information about the artists/groups, the instruments and the music they play and any other information we think might interest you. An important note. You will see next to the titles of each album on each page a product number (EUCD then a number). This is our reference number for each album. If you should ever encounter any difficulties obtaining our CDs in record stores please contact us through the appropriate company for your country on the back page of this catalogue - we will help you to get our music. Enjoy the catalogue, please contact us at any time to order and enjoy wonderful music from around the world with ARC Music. Best wishes, the ARC Music team. SPECIAL NOTE Instrumental albums in TOP 10 Best-Selling RELEASES 2007/2008 our catalogue are marked with this symbol: 1. -

Curva Minore Contemporary Sounds Musica Nuova in Sicilia 1997/2007

Un museo etnografico edita una pubblicazione Why has an ethnographic museum published a 7 4/5 0 sull’attività di un’Istituzione che si occupa di musica book on the activities carried out by an Institution 0 2 contemporanea: perché? that deals with contemporary music? / Molte le possibili risposte, numerose quelle legate There are several answers, all of which trace back to 7 9 al lascito ideale del suo fondatore, Antonino Uccello the legacy left by the ethnographic museum’s 9 1 (1922-1979), intellettuale ad ampio raggio, poeta, founder, Antonino Uccello (1922-1979), to whom A I studioso non accademico di antropologia, this work is dedicated. Uccello was an intellectual L I anticonformista e scomodo operatore culturale with a wide range of interests, a poet, a non- C I S nella Sicilia degli anni Sessanta e Settanta, academic anthropology scholar, an eccentric and A N cui questo lavoro costituisce un omaggio. challenging cultural expert of Sicily in the 1960s I Casa museo Antonino Uccello V Nella pervicace volontà di proporre nuove soluzioni and 1970s. In his determination to offer new a cura di Gaetano Pennino A E V per le offerte culturali più avanzate e per le sfide solutions for the most cutting-edge cultural featuring english translation of selected chapters O U istituzionali più ardite, Uccello rivelò il senso initiatives and the most daring institutional R N dell’impegno di una vita spesa per l’affermazione challenges, Uccello gave proof of his commitment R A C U di un principio che oggi può configurarsi risibile to forwarding a principle, which today is vested of I S velleità: intendere la realtà in cui si vive per poterla absurd ambition: understanding the reality we live O U C cambiare, trasformare . -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Allarme Attentati I T O Bomba Autostrada

Giornale + libro iDS Collana i grandi processi aa Consorzio Cooperative Abitazione GRAMSCI, Consorzio Cooperative Abitazione + DOV'È WALLY Multi JIEBC0LED120 APRILE 1994- L 2.500 «MÌL 5.000 Trovata a Massa. Un pentito nel mirino? Gli avvocati Allarme attentati del Ito bomba Cavaliere OIUSEPPECACDAROLA } ON. BERLUSCO- autostrada ' NI avrebbe già preparato la li sta dei ministri • Sette candelotti di dinamite sotto il cavalcavia dell'autostrada Livor del suo governo. " no-Genova che dalle 13 alle 15 è rimasta chiusa al traffico nei due sensi. ___L i L'elenco è se Una bomba per il pentito Luciano Tancredi, che ha svelato gli affari e i greto, dicono. Si sa però -lo dicono fonti di Forza Italia - delitti del clan del boss Carmelo Musumeci? Proprio ieri, dinanzi al Tribu che il futuro premier sta ten nale di La Spezia, il pm ha chiesto la condanna all'ergastolo di Musumeci tando il colpo grosso: convin • e una raffica di pesanti condanne per gli altri imputati. Grazie alle confes cere il giudice Di Pietro ad as sioni di Tancredi, inoltre, la Dia di Firenze ha potuto trovare le prove a ca sumere la guida degli Interni rico del clan mafioso che gestiva l'autoparco di via Salomone a Milano. o della Giustizia. Di Pietro, Gli artificieri hanno fatto brillare l'involucro, un barattolo di marmellata, e fanno sapere le stesse fonti, recuperato i candelotti. L'esplosivo collegato con una miccia ad un deto sarebbe orientato al no. Ma la natore, è stato scoperto in seguito ad una telefonata anonima. «Sembra la lista, ancorché segreta, è af fotocopia della bomba rinvenuta a Roma, anche se il quantitativo è molto follata di altri nomi ed e stata infenore». -

Cahiers D'ethnomusicologie, 13

Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie Anciennement Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles 13 | 2001 Métissages Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/657 ISSN : 2235-7688 Éditeur ADEM - Ateliers d’ethnomusicologie Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 janvier 2001 ISBN : 2-8257-0723-6 ISSN : 1662-372X Référence électronique Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie, 13 | 2001, « Métissages » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 14 décembre 2011, consulté le 06 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/657 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 6 mai 2019. Tous droits réservés 1 Un courant important de la création artistique contemporaine, tant savante que populaire, est fondé sur les rencontres et les emprunts interculturels. Le phénomène n’est cependant pas nouveau : réalité tant physique que sociale et culturelle, le métissage adopte en musique des formes extrêmement variées. Quelles en sont les modalités ? Comment le métissage s’opère-t-il dans tel ou tel contexte ? En quoi se différencie-t-il des cas de "fusion" et d’hybridation liées à la world music moderne ? En définitive, toute musique ne témoigne-t-elle pas, à un degré ou à un autre, de processus de métissage ? C’est à ce type de questions que ce volume tente d’apporter des éléments de réponse à travers une série d’études, non seulement sur les grandes cultures métissées comme celles qu’on peut les observer sur le continent américain, mais aussi sur des cas particuliers significatifs de métissage historique ou, a contrario, sur des expériences récents de rencontre interculturelle pouvant contenir les germes de phénomènes durables. Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie, 13 | 2001 2 SOMMAIRE Dossier: Métissages Le métissage en musique : un mouvement perpétuel (Amérique du Nord et Afrique du Sud) Denis-Constant Martin Systèmes rythmiques, métissages et enjeux symboliques des musiques d’Amérique latine Michel Plisson Le Tresillo rythme et « métissage » dans la musique populaire latino-américaine imprimée au XIXe siècle Carlos Sandroni La culture musicale des Garifuna. -

Exploring an Instrument's Diversity: Carmen Liliana Troncoso Cáceres Phd University of York Music September 2019

Exploring an Instrument’s Diversity: The Creative Implications of the Recorder Performer’s Choice of Instrument Volume I Carmen Liliana Troncoso Cáceres PhD University of York Music September 2019 2 Abstract Recorder performers constantly face the challenge of selecting particular instrumental models for performance, subject to repertoire, musical styles, and performance contexts. The recorder did not evolve continuously and linearly. The multiple available models are surprisingly dissimilar and often somewhat anachronistic in character, juxtaposing elements of design from different periods of European musical history. This has generated the particular and peculiar situation of the recorder performer: the process of searching for and choosing an instrument for a specific performance is a complex aspect of performance preparation. This research examines the variables that arise in these processes, exploring the criteria for instrumental selection and, within the context of music making, the creative possibilities afforded by those choices. The study combines research into recorder models and their origins, use and associated contexts with research through performance. The relationship between performer and instrument, with its cultural and personal complexities, is significant here. As an ‘everyday object’, rooted in daily practice and personal artistic expression over many years, the instrument becomes part of the performer’s identity. In my case, as a Chilean performing an instrument that, despite its wider connection to a range of other duct flutes across the world, belongs to European culture, this sense of identity is complex and therefore examined in my processes of selecting and working creatively with the instruments. This doctorate portfolio comprises six performance projects, encompassing new, collaboratively developed works for a variety of recorders, presented through performance and recorded media.