Shawms Around the World © Jeremy Montagu 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

Perceptual Interactions of Pitch and Timbre: an Experimental Study on Pitch-Interval Recognition with Analytical Applications

Perceptual interactions of pitch and timbre: An experimental study on pitch-interval recognition with analytical applications SARAH GATES Music Theory Area Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University Montréal • Quebec • Canada August 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. Copyright © 2015 • Sarah Gates Contents List of Figures v List of Tables vi List of Examples vii Abstract ix Résumé xi Acknowledgements xiii Author Contributions xiv Introduction 1 Pitch, Timbre and their Interaction • Klangfarbenmelodie • Goals of the Current Project 1 Literature Review 7 Pitch-Timbre Interactions • Unanswered Questions • Resulting Goals and Hypotheses • Pitch-Interval Recognition 2 Experimental Investigation 19 2.1 Aims and Hypotheses of Current Experiment 19 2.2 Experiment 1: Timbre Selection on the Basis of Dissimilarity 20 A. Rationale 20 B. Methods 21 Participants • Stimuli • Apparatus • Procedure C. Results 23 2.3 Experiment 2: Interval Identification 26 A. Rationale 26 i B. Method 26 Participants • Stimuli • Apparatus • Procedure • Evaluation of Trials • Speech Errors and Evaluation Method C. Results 37 Accuracy • Response Time D. Discussion 51 2.4 Conclusions and Future Directions 55 3 Theoretical Investigation 58 3.1 Introduction 58 3.2 Auditory Scene Analysis 59 3.3 Carter Duets and Klangfarbenmelodie 62 Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux • Carter and Klangfarbenmelodie: Examples with Timbral Dissimilarity • Conclusions about Carter 3.4 Webern and Klangfarbenmelodie in Quartet op. 22 and Concerto op 24 83 Quartet op. 22 • Klangfarbenmelodie in Webern’s Concerto op. 24, mvt II: Timbre’s effect on Motivic and Formal Boundaries 3.5 Closing Remarks 110 4 Conclusions and Future Directions 112 Appendix 117 A.1,3,5,7,9,11,13 Confusion Matrices for each Timbre Pair A.2,4,6,8,10,12,14 Confusion Matrices by Direction for each Timbre Pair B.1 Response Times for Unisons by Timbre Pair References 122 ii List of Figures Fig. -

Final Program for the ATS International Conference Is Available in Printed and Digital Format

WELCOME TO ATS 2017 • WASHINGTON, DC Welcome to ATS 2017 Welcome to Washington, DC for the 2017 American Thoracic Society International Conference. The conference, which is expected to draw more than 15,000 investigators, educators, and clinicians, is truly the destination for pediatric and adult pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine professionals at every level of their careers. The conference is all about learning, networking and connections. Because it engages attendees across many disciplines and continents, the ATS International Conference draws a large, diverse group of participants, a dedicated and collegial community that inspires each of us to make a difference in patients’ lives, now and in the future. By virtue of its size — ATS 2017 features approximately 6,700 original research projects and case reports, 500 sessions, and 800 speakers — participants can attend David Gozal, MD sessions and special events from early morning to the evening. At ATS 2017 there will be something for President everyone. American Thoracic Society Don’t miss the following important events: • Opening Ceremony featuring a keynote presentation by Nobel Laureate James Heckman, PhD, MA, from the Center for the Economics of Human Development at the University of Chicago. • Ninth Annual ATS Foundation Research Program Benefit honoring David M. Center, MD, with the Foundation’s Breathing for Life Award on Saturday. • ATS Diversity Forum will feature Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, MD, Director, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health. • Keynote Series highlight state of the art lectures on selected topics in an unopposed format to showcase major discoveries in pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine. -

Catalogue 2021

medir .cat Catalogue 2021 Summary Clarinet Sax Historic Instruments Bassoon Oboe & English Horn Traditional & Folk Bag Pipe & Uilleann Pipe Cork Summary Clarinet 04 Sax 12 Historic Instruments 21 Bassoon 28 Oboe & English Horn 51 Traditional & Folk Instruments 73 Bag pipe & Uilleann Pipe 79 Cork 88 medir.cat 03 Clarinet medir.cat 04 Summary Clarinet Sax Historic Instruments Bassoon Oboe & English Horn Traditional & Folk Bag Pipe & Uilleann Pipe Cork Medir Reeds C108 Bb Clarinet - 10 pieces C1085 Bb Clarinet - 5 pieces C117 Eb Clarinet - 10 pieces C1175 Eb Clarinet - 5 pieces Strenght: 1,5 / 2 / 2,5 / 3 / 3,5 / 4 / 4,5 / 5 C113 Bass Clarinet - 10 pieces C1135 Bass Clarinet - 5 pieces C108 C1085 Strenght: 2 / 2,5 / 3 / 3,5 / 4 / 4,5 C113 C108 medir.cat 05 Summary Clarinet Sax Historic Instruments Bassoon Oboe & English Horn Traditional & Folk Bag Pipe & Uilleann Pipe Cork Medir Cane C101 Clarinet Tube Cane - 1 Kg Diameter: >25mm / Thickness >3 mm C103 Bb Clarinet Splits - 100 pieces Length: 69 mm / Thickness: >3 mm C104 Bb Clarinet Flat Blank - 100 pieces Length: 69 mm / Thickness: 2,2 mm C101 C103 C105 Bb Clarinet Blanks - 100 pieces Filled / Unfilled C106 Bb German Clarinet Blanks - 100 pieces C107 Eb Petit Clarinet Blanks - 100 pieces Filled C104 C105 medir.cat 06 Summary Clarinet Sax Historic Instruments Bassoon Oboe & English Horn Traditional & Folk Bag Pipe & Uilleann Pipe Cork Mouthpieces C110B Bb Clarinet C110E Eb Clarinet C110BS Bb Bass Clarinet Tip opening: close, 3, 4, 5, 6, open Ligatures C111 C111B Bb Clarinet C111E Eb Clarinet -

Interstellar Music - by Mike Overly

Interstellar Music - by Mike Overly Let's imagine that you could toss a message in a bottle faster than a speeding bullet into the cosmic ocean of outer space. What would you seal inside it for anyone, or anything, to open some day in the distant future, in a galaxy far, far away from our solar system? Well, imagine no more because it's been done! Thirty-five years ago, NASA launched two Voyager spacecraft carrying earthly images and sounds toward the Stars. Voyager 1 was launched on September 5, 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida and Voyager 2 was sent on its way August 20 of that same year. Voyager 1 is now 11 billion miles away from earth and is the most distant of all human-made objects. Everyday, it flies another million miles farther. In fact, Voyager 1 and 2 are so far out in space that their radio signals, traveling at the speed of light, take 16 hours to reach Earth. These radio signals are captured daily by the big dish antennas of the Deep Space Network and arrive at a strength of less than one femtowatt, a millionth of a billionth of a watt. Wow! Both Voyagers are headed towards the outer boundary of the solar system, known as the heliopause. This is the region where the Sun's influence wanes and interstellar space waxes. Also, the heliopause is where the million-mile-per-hour solar winds slow down to about 250,000 miles per hour. The Voyagers have reached these solar winds, also known as termination shock, and should cross the heliopause in another 10 to 20 years. -

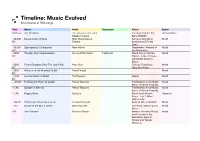

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

WOODWIND INSTRUMENT 2,151,337 a 3/1939 Selmer 2,501,388 a * 3/1950 Holland

United States Patent This PDF file contains a digital copy of a United States patent that relates to the Native American Flute. It is part of a collection of Native American Flute resources available at the web site http://www.Flutopedia.com/. As part of the Flutopedia effort, extensive metadata information has been encoded into this file (see File/Properties for title, author, citation, right management, etc.). You can use text search on this document, based on the OCR facility in Adobe Acrobat 9 Pro. Also, all fonts have been embedded, so this file should display identically on various systems. Based on our best efforts, we believe that providing this material from Flutopedia.com to users in the United States does not violate any legal rights. However, please do not assume that it is legal to use this material outside the United States or for any use other than for your own personal use for research and self-enrichment. Also, we cannot offer guidance as to whether any specific use of any particular material is allowed. If you have any questions about this document or issues with its distribution, please visit http://www.Flutopedia.com/, which has information on how to contact us. Contributing Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office - http://www.uspto.gov/ Digitizing Sponsor: Patent Fetcher - http://www.PatentFetcher.com/ Digitized by: Stroke of Color, Inc. Document downloaded: December 5, 2009 Updated: May 31, 2010 by Clint Goss [[email protected]] 111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007563970B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,563,970 B2 Laukat et al. -

7'Tie;T;E ~;&H ~ T,#T1tmftllsieotog

7'tie;T;e ~;&H ~ t,#t1tMftllSieotOg, UCLA VOLUME 3 1986 EDITORIAL BOARD Mark E. Forry Anne Rasmussen Daniel Atesh Sonneborn Jane Sugarman Elizabeth Tolbert The Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology is an annual publication of the UCLA Ethnomusicology Students Association and is funded in part by the UCLA Graduate Student Association. Single issues are available for $6.00 (individuals) or $8.00 (institutions). Please address correspondence to: Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology Department of Music Schoenberg Hall University of California Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA Standing orders and agencies receive a 20% discount. Subscribers residing outside the U.S.A., Canada, and Mexico, please add $2.00 per order. Orders are payable in US dollars. Copyright © 1986 by the Regents of the University of California VOLUME 3 1986 CONTENTS Articles Ethnomusicologists Vis-a-Vis the Fallacies of Contemporary Musical Life ........................................ Stephen Blum 1 Responses to Blum................. ....................................... 20 The Construction, Technique, and Image of the Central Javanese Rebab in Relation to its Role in the Gamelan ... ................... Colin Quigley 42 Research Models in Ethnomusicology Applied to the RadifPhenomenon in Iranian Classical Music........................ Hafez Modir 63 New Theory for Traditional Music in Banyumas, West Central Java ......... R. Anderson Sutton 79 An Ethnomusicological Index to The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Part Two ............ Kenneth Culley 102 Review Irene V. Jackson. More Than Drumming: Essays on African and Afro-Latin American Music and Musicians ....................... Norman Weinstein 126 Briefly Noted Echology ..................................................................... 129 Contributors to this Issue From the Editors The third issue of the Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology continues the tradition of representing the diversity inherent in our field. -

Tuning In” Podcast Terminology

H+H “TUNING IN” PODCAST TERMINOLOGY Alto A designation for a range of the human voice, between soprano and tenor. Both women and men perform in the alto range. Aria A song movement which features a soloist singing in a steady tempo (as opposed to the unmeasured, sung-speech style of the recitativ). In addition to the standard continuo accompaniment, an aria can call for a few additional instruments and sometimes even feature a solo instrument, such as the solo violin in “Erbarme dich”. Bass Used to describe a musical instrument and the lowest line of music, in this case it refers to a range of the human voice below tenor. Bass line The lowest written line of music, usually carried out by instruments such as cellos and double basses along with a doubling keyboard instrument such as the organ or harpsichord. In some instances, Bach composes a bass line for an instrument in a higher range, such as the oboe da caccia, but keeps the voice and other instrument or instruments above that range. Chorale A movement which typically features a four-part hymn supported by the orchestra such that the high-pitched instruments play the same line as the sopranos, mid-range instruments play the alto line, etc.; in a Lutheran service, chorale movements allowed the congregation to join in song. Continuo As in Basso Continuo, or “Continuous Bass.” Refers to the group of players who play the lowest line of the music, typically a keyboard instrument such as organ or harpsichord, sometimes a plucked instrument such as theorbo (bass lute), and a sustaining instrument such as the cello; bass instruments which provide the harmonic foundation throughout the entire Passion, even in solo vocal movements (for which the rest of the orchestra does not play). -

Early Music Performer

EARLY MUSIC PERFORMER JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL EARLY MUSIC ASSOCIATION ISSUE 29 November 2011 I.S.S.N 1477-478X Ruth and Jeremy Burbidge THE PUBLISHERS Ruxbury Publications Scout Bottom Farm Hebden Bridge West Yorkshire HX7 5JS • SANTIAGO DE MURCIA, CIFRAS 2 SELECTAS DE GUITARRA Martyn Hodgson EDITORIAL Andrew Woolley 21 4 MUSIC SUPPLEMENT • FACSIMILES OF SONGS FROM THE / ARTICLES SPINNET: / OR MUSICAL / MISCELLANY • MORROW, MUNROW AND MEDIEVAL (London, 1750) MUSIC: UNDERSTANDING THEIR INFLUENCE AND PRACTICE Edward Breen 24 PUBLICATIONS LIST • DIGITAL ARCHIVES AT THE ROYAL LIBRARY, COPENHAGEN Matthew Hall Peter Hauge COVER: An illustration of p. 44 from the autograph manuscript for J. A. Sheibe’s Passionscantate (1768) (Royal Library, Copenhagen, Gieddes Samling, XI, 11 24). It shows a highly dramatic recitative (‘the curtain is torn and the holy flame penetrates the abominable REPORT darkness’). At first sight the manuscript seems easy to read; however, Scheibe’s notational practice in terms • THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL of accidentals creates problems for the modern CONFERENCE ON HISTORICAL KEYBOARD editor. Scheibe wrote extensively on the function of MUSIC recitative, and especially on the subtle distinction between declamation and recitative. (Peter Hauge) Andrew Woolley 13 REVIEWS • PETER HOLMAN, LIFE AFTER DEATH: THE VIOLA DA GAMBA IN BRITAIN FROM PURCELL TO DOLMETSCH EDITOR: Andrew Woolley [email protected] Nicholas Temperley EDITORIAL BOARD: Peter Holman (Chairman), • GIOVANNI STEFANO CARBONELLI: Clifford Bartlett, Clive Brown, Nancy Hadden, Ian XII SONATE DA CAMARA, VOLS. 1 & 2, ED. Harwood, Christopher Hogwood, David Lasocki, Richard MICHAEL TALBOT Maunder, Christopher Page, Andrew Parrott, Richard Rastall, Michael Talbot, Bryan White Peter Holman ASSISTANT EDITORS: Clive Brown, Richard Rastall EDITORIAL ASSISTANT: Matthew Hall 1 Editorial I am a regular visitor, as I’m sure many readers are, to the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) or the Petrucci Music Library (http://imslp.org.uk). -

C Quliyev Bayati 2Cild.Pdf

Bayatı "ATLAS ENSEMBLE" üçün p a r t i t u r a *** Bayaty for "ATLAS ENSEMBLE" s c o r e ORCHESTRA: Flute / Piccolo Dizi / Xun in C Ney in C Suona / Guanzi in C Zurna in C Oboe Balaban in C Sheng 1 in C Sheng 2 in C Clarinetti in B / in A / Basso Clarinetto Pipa / Liugin in C Tar in C Ud in C Mandolin Kanun in C Zheng in C Santur in C Arpa Timpani Piatto sospeso Cinese tom-toms Tam-Tam Soprano Female khanende singer Violino Erhu in C Kamancha in D Kemenche in C Viola Viola da gamba Violoncello Contrabass ATLAS ENSEMBLE-nin (HOLLANDİYA) SİFARİŞİ İLƏ - 2004 COMMISSIONED BY ATLAS ENSEMBLE (NEDERLAND) - 2004 Bayatı Bayaty Cavanşir QULİYEV Javanshir GULIYEV q=135 > Piccolo > œ œ >œ œ œ œ œ >œ bœ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ bœ œ œ œ Flute/Picc. 4 j œ œ #œ œ œ #œ œ °& 4 Œ ‰ œ J ‰ Dizi f > œ œ œ > œ œ >œ œ œ œ œ >œ bœ œ œ œ #œ œ bœ œ œ Dizi/xun inC 4 j œ œ #œ œ œ #œ œ & 4 Œ ‰ œ J ‰ f > > > #>œ œ œ œ œ œ Ney in C 4 j #œ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ & 4 Œ ‰ œ œ œ œ J ‰ ¢ Guanzi f Suona/Guanzi in C 4 °& 4 j ‰ Œ Ó ∑ ∑ f œ > Zurna in C 4 œ & 4 ‰ Œ Ó ∑ ∑ f J > > œ œ >œ œ œ œ œ >œ bœ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ bœ œ œ œ Oboe 4 j œ œ #œ œ œ #œ œ & 4 Œ ‰ œ J ‰ f > Balaban in C 4 j j œ œ œ & 4 Œ ‰ œ #œ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ bœ œ œ œ ‰ #œ œ bœ œ œ ¢ f œ œ > œ > > Sheng in C 1 4 j °& 4 œ ‰ Œ Ó ∑ ∑ f Sheng in C 2 4 & 4 j ‰ Œ Ó ∑ ∑ f œ Cl.