7343 Bagpipe in Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universiv Micrmlms Internationcil

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microHlming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify m " '<ings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyriglited materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin film ing at the upper le ft hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections w ith small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Riflessioni Sul Potere Dell'im- Maginazione E Dei Suoi Limiti 'Ocos

_ Anno X N. 97 | Settembre 2021 | ISSN 2431 - 6739 Cannes 2021: riflessioni sul potere dell’im- ‘Ocos maginazione e dei suoi limiti Nasciamo e ci mettiamo ad ardere, finché il fumo dilegua come fumo. Il festival di Cannes si Non sono presenti in queste opere rappresen- Yehuda Amichai - Poesie è svolto nel mese dello tazioni distopiche sul virus, cioè non sono a cura di Ariel Rathaus scorso Luglio, fuori dal emerse ad esempio riflessioni sulla ripresa Milano, Crocetti, 1993, 2001 suo tempo canonico. La economica dopo lo shock della crisi sanitaria. volontà dell’organizza- E sono pochissime le scene cinematografiche zione è stata quella di in cui la trama del film abbia fatto vedere ma- È un paesaggio che mostrare la capacità di scherine coprire il viso dei personaggi. È la ri- non ha niente a che ve- saper realizzare un prova che nel cinema contemporaneo si sia dere con La hora de los grande evento di spet- sviluppata una crescente difficoltà per molti hornos (1968), il docu- tacolo in piena pan- cineasti di saper trattare il tema identitario in Àngel Quintana mentario di Fernando demia. Con il deside- un mondo così complesso. Solanas e Octavio Ge- rio di voler dimostrare che la cultura si può A Chiara, il film di Jonas Carpignano, si rac- tino sul neocoloniali- salvare nonostante tutto. Molti dei film pre- conta dell’esperienza di una ragazza che, do- smo e sulle rivoluzioni sentati a Cannes si trovavano da più di un an- po la scomparsa del padre, vive una nuova Natalino Piras della martoriata Ame- no bloccati a causa della chiusura delle sale ci- condizione che la obbliga a interrogarsi sulla rica Latina, sul finire degli anni Sessanta del nematografiche, altre pellicole sono state sua reale identità e, conseguentemente, su co- secolo scorso. -

La Flauta I Tambor a La Musica Ktnica Catalana

Recerca Musicolbgica VI-VII, 1986-1987, 173-233 La flauta i tambor a la musica ktnica catalana GABRIEL FERRE I PUIG A la Mer& Per6 I'instrument musical es troba íntimament vinculat a la vida social d'un nucli determinat. Encara que sigui essencialment ['element transmis- sor d'una substcincia tan immaterial com és la música, té inherents fun- cions estretament vinculades amb els ritus, les institucions, les activitats de tipus cultural, ideologic i semal dels diferents grups humans. Josep Crivillé. És ben cert que entre l'instrument de música i la vida de la humani- tat existeix una relació evident. Aquest lligam estret s'observa en l'evo- lució de l'instrument musical i el desenvolupament de la vida humana: la transformació morfolbgica, musical i simbblica de l'instrument i I'activitat material, artística i espiritual de l'home durant la historia. I a més d'aquesta reflexió genkrica i universal, en la música ktnica cal afegir que I'instrument pren uns trets particulars atesa la seva vincula- ció a la sensibilitat i al patrimoni cultural propis de cada poble. Aquestes consideracions generals estableixen un marc teoric que, de fet, regeix aquest article can no pretenc sinó exposar unes breus notes de treball a l'entorn de dos instruments musicals ktnics catalans: la flauta i tambor. Mitjan~antI'observació de diversos instruments des- crits i I'audició d'uns docluments sonors enregistrats, assajaré d'ende- gar un estudi comparatiu que ha de conduir a la codificació d'uns trets ktnics específics existents. En aquest sentit, sera interessant advertir les característiques morfologiques i estilístiques acostades o allunyades dels S diversos instruments localitzats a les distintes regions del territori na- cional dels Paisos Catalans: Principat de Catalunya, Illes Balears i País Valencia. -

The History and Revival of the Meråker Clarinet

MOT 2016 ombrukket 4.qxp_Layout 1 03.02.2017 15.49 Side 81 “I saw it on the telly” – The history and revival of the Meråker clarinet Bjørn Aksdal Introduction One of the most popular TV-programmes in Norway over the last 40 years has been the weekly magazine “Norge Rundt” (Around Norway).1 Each half-hour programme contains reports from different parts of Norway, made locally by the regional offices of NRK, the Norwegian state broad- casting company. In 1981, a report was presented from the parish of Meråker in the county of Nord-Trøndelag, where a 69-year old local fiddler by the name of Harald Gilland (1912–1992), played a whistle or flute-like instrument, which he had made himself. He called the instrument a “fløit” (flute, whistle), but it sounded more like a kind of home-made clarinet. When the instrument was pictured in close-up, it was possible to see that a single reed was fastened to the blown end (mouth-piece). This made me curious, because there was no information about any other corresponding instrument in living tradition in Norway. Shortly afterwards, I contacted Harald Gilland, and we arranged that I should come to Meråker a few days later and pay him a visit. The parish of Meråker has around 2900 inhabitants and is situated ca. 80 km northeast of Trondheim, close to the Swedish border and the county of Jamtlandia. Harald Gilland was born in a place called Stordalen in the 1. The first programme in this series was sent on October 2nd 1976. -

Selva De Varii Passaggi

Francesco Rognoni Selva de Varii Passaggi (1620) Avvertimenti alli Benigni Lettori Translated by Sion M. Honea 1 Translator’s Preface We must be grateful for Rognoni’s book, but it must also stand as something of an enigmatic anachronism. Rognoni’s exact dates are uncertain, but he was no doubt middle-aged by 1620, the date of publication. His father Riccardo had published his own book in 1592, at what seems to have been the height, or more likely the last flowering of the diminution technique in the 1590’s, along with those of Conforto, Bovicelli and Zacconi. Maffei had produced the essential document on the subject in 1562 and Caccini delivered the first blow to, or perhaps the eulogy on it in 1601, dismissing it as an irrelevant anachronism from a bygone age. This in fact it was. In a sense, the practice has more in common with the several techniques of improvised counterpoint on chant melodies that medieval choristers trained in, and even seems rather a holdover as applied to the renaissance motet or madrigal. It was a technique of thrillingly virtuosic potential but essentially barren of internal emotional significance. Rognoni himself realized this, it seems, and presents a startling indictment of singers who saw themselves, their voices and their technique of greater value than the words and the affect. More importantl evidence of his understanding is that his book begins with his superb presentation of the types of ornaments that Caccini’s new emotional performance used. Then it moves on to the diminution technique as incorporating these elements of the new style.1 The book is in two parts, the first for voice and the second for instruments. -

The Indigenous Healing Tradition in Calabria, Italy

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 30 Article 6 Iss. 1-2 (2011) 1-1-2011 The ndiI genous Healing Tradition in Calabria, Italy Stanley Krippner Saybrook University Ashwin Budden University of California Roberto Gallante Documentary Filmmaker Michael Bova Consciousness Research and Training Project, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Krippner, S., Budden, A., Gallante, R., & Bova, M. (2011). Krippner, S., Budden, A., Bova, M., & Gallante, R. (2011). The indigenous healing tradition in Calabria, Italy. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 30(1-2), 48–62.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 30 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2011.30.1-2.48 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Indigenous Healing Tradition in Calabria, Italy1 Stanley Krippner Saybrook University Ashwin Budden San Francisco, CA, USA Roberto Gallante University of California Documentary Filmmaker San Diego, CA, USA Michael Bova Rome, Italy Consciousness Research and Training Project, Inc. Cortlandt Manor, NY, USA In 2003, the four of us spent several weeks in Calabria, Italy. We interviewed local people about folk healing remedies, attended a Feast Day honoring St. Cosma and St. Damian, and paid two visits to the Shrine of Madonna dello Scoglio, where we interviewed its founder, Fratel Cosimo. -

Pilgrimage to Accordionland by Fabio G

Pilgrimage to Accordionland By Fabio G. Giotta Italy shares the musical traditions of the accordion with all of Europe, especially France, Germany, Poland, and Scandinavia, but it was Giuseppe Verdi that recognized it as a “proper” instrument and recommended its induction to conservatories of music. No matter your perceptions, Italy truly owns the accordion. Picture Italy’s central Adriatic (Eastern) coast. Some may know this area because of major shipping port of Ancona, or for the city of Pesaro, home of music composers Gioacchino Rossini and, more recently Riz Ortolani, soprano Renata Tebaldi, or even for championship winning, exotic Benelli Motorcycles-perhaps the longest continuously operating firm in its field, having produced the world’s first 6 cylinder production bike which “sings” its way down the road (how Italian!) Even lesser known Recanati lays claim to tenor Beniamino Gigli. However, these wonderful, must see attractions are secondary to me. More important to this accordionist (and my new accordion recruit, my Lady, Angela) is the musical pilgrimage to “Accordionland Central”, specifically, picturesque hilltop town Castelfidardo and its surrounding hilltop, accordion hamlets of Camerano (home of Scandalli accordions), Numana (home of Frontalini accordions), Loreto (home of the Blessed Mother’s house and the “accordion piazza”) and even Recanati (partial home of Fratelli Vaccari accordions). In the historic center of Castelfidardo, is the “Museo Internazionale Della Fisarmonica”, that is, the International Museum of the Accordion, established in1981 (City of Castelfidardo web site: http://www.comune.castelfidardo.an.it/visitatore/index. php?id=50004 OR alternate site-English language : http://accordions.com/museum/ Left to right; Paolo Brandoni, the author, and Maurizio Composini Multiple curators with a great love for music and the accordion maintain the Museum pristinely and operate it impeccably. -

The Zampognari

Ottawa November 2014 PRESS RELEASE VISIT TO OTTAWA OF THE ZAMPOGNARI DI BOIANO (TRADITIONALLY DURING THE CHRISTMAS SEASON, BAGPIPE PLAYERS VISITED VILLAGES THROUGHOUT ITALY BRINGING A MESSAGE OF PEACE BY PLAYING SEASONAL MUSIC ON THEIR UNIQUE INSTRUMENTS.) The Molisani Association of Ottawa, founded in 2008, is an association whose aim is to maintain in the Ottawa area, the cultural traditions of the region of Molise in Italy. The Association is hosting the Zampognari di Boiano from December 11th to December 17th. Three bagpipe players from that Region will appear in several performances as well as at fundraising event for the Italian-Canadian Historical Centre recently built on the grounds of Villa Marconi on Baseline Road. The Historical Centre is a gathering place where the contributions made by generations of Italian immigrants to Canada is celebrated in the form of exhibits, educational, cultural and heritage presentations and storage of personal, symbolic stories that have marked the last century of Italian – Canadian immigration of Canadian History. Along with the Molisani Association of Ottawa, many individuals and businesses have offered to support this initiative financially – conscious of the fact that this initiative presents to Ottawans a rare opportunity to experience the spirit of Christmas performed in the time-honoured tradition of Italian bagpipe musicians and to celebrate the richness of Italian culture. The Zampognari di Boiano have performed in Ottawa on two previous occasions, in 2008 and 2010, at which time they donated two of their original handmade instruments to the Canadian Museum of History. For more information please contact me at the following: E-Mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Phone: H: 613 236-4314 O: 613 232-5689 C: 613 252-0114 OR Josephine Palumbo, President National Congress of Italian Canadians (Ottawa Region) at 613 521-2886 Paolo Siraco President Additional background notes on the Zampognari are appended. -

Download (12MB)

10.18132/LFZE.2012.21 Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti Egyetem 28. számú művészet- és művelődéstörténeti tudományok besorolású doktori iskola KELET-ÁZSIAI DUPLANÁDAS HANGSZEREK ÉS A HICHIRIKI HASZNÁLATA A 20. SZÁZADI ÉS A KORTÁRS ZENÉBEN SALVI NÓRA TÉMAVEZETŐ: JENEY ZOLTÁN DLA DOKTORI ÉRTEKEZÉS 2011 10.18132/LFZE.2012.21 SALVI NÓRA KELET-ÁZSIAI DUPLANÁDAS HANGSZEREK ÉS A HICHIRIKI HASZNÁLATA A 20. SZÁZADI ÉS A KORTÁRS ZENÉBEN DLA DOKTORI ÉRTEKEZÉS 2011 Absztrakt A disszertáció megírásában a fő motiváció a hiánypótlás volt, hiszen a kelet-ázsiai régió duplanádas hangszereiről nincs átfogó, ismeretterjesztő tudományos munka sem magyarul, sem más nyelveken. A hozzáférhető irodalom a teljes témának csak egyes részeit öleli fel és többnyire valamelyik kelet-ázsiai nyelven íródott. A disszertáció második felében a hichiriki (japán duplanádas hangszer) és a kortárs zene viszonya kerül bemutatásra, mely szintén aktuális és eleddig fel nem dolgozott téma. A hichiriki olyan hangszer, mely nagyjából eredeti formájában maradt fenn a 7. századtól napjainkig. A hagyomány előírja, hogy a viszonylag szűk repertoárt pontosan milyen módon kell előadni, és ez az előadásmód több száz éve gyakorlatilag változatlannak tekinthető. Felmerül a kérdés, hogy egy ilyen hangszer képes-e a megújulásra, integrálható-e a 20. századi és a kortárs zenébe. A dolgozat első részében a hozzáférhető szakirodalom segítségével a szerző áttekintést nyújt a duplanádas hangszerekről, bemutatja a két alapvető duplanádas hangszertípust, a hengeres és kúpos furatú duplanádas hangszereket, majd részletesen ismerteti a kelet-ázsiai régió duplanádas hangszereit és kitér a hangszerek akusztikus tulajdonságaira is. A dolgozat második részéhez a szerző összegyűjtötte a fellelhető, hichiriki-re íródott 20. századi és kortárs darabok kottáit és hangfelvételeit, és ezek elemzésével mutat rá a hangszerjáték új vonásaira. -

Marco De Referencia Para El Área De Aprendizaje De Desarrollo Global

Marco de referencia para el área de aprendizaje de Desarrollo Global Marco de referencia para el área de aprendizaje de desarrollo global en el marco de una Educación para el desarrollo sostenible 2ª edición actualizada y ampliada, 2016 Una contribución al programa de acción internacional “Educación para el desarrollo sostenible” Confeccionado y editado por: Jörg-Robert Schreiber y Hannes Siege Resultado del proyecto en conjunto con la Conferencia de Ministros de Educación y Ciencia (KMK, por sus siglas en alemán) y el Ministerio Federal de Cooperación Económica y Desarrollo (BMZ, por sus siglas en alemán) 2004–2015, Bonn Por encargo de: La Conferencia Permanente de los Ministros de Cultura de los Estados Federados de la República Federal de Alemania www.kmk.org, Correo electrónico: [email protected] Taubenstraße 10, D-10117 Berlin Código postal 11 03 42, D-10833 Berlín Tel. +49 (0) 30 254 18-499 Fax +49 (0) 30 254 18-450 Ministerio Federal de Cooperación Económica y Desarrollo www.bmz.de, Correo electrónico: [email protected] Sede Bonn Código postal 12 03 22, D-53045 Bonn Tel. +49 (0) 228 99 535-0 Fax +49 (0) 228 99 535-2500 Sede Berlin Stresemannstraße 94, D-10963 Berlin Tel. +49 (0) 30 18 535-0 Fax +49 (0) 30 18 535-2501 Publicado por: ENGAGEMENT GLOBAL gGmbH Servicio para iniciativas de desarrollo Tulpenfeld 7, D-53113 Bonn Tel. +49 (0) 228 20717-0 Fax +49 (0) 228 20717-150 www.engagement-global.de Correo electrónico: [email protected] Redacción: Jörg Peter Müller Diseño: zweiband.media, Berlín Implementación tecnológica: -

The Organ. a Natural Poj' Cutjctijjouru Is Included with the Italian Sibility Exists Lbat a Few of the In· Pieces

THE DIAPASON AN INTERNATIONAL MONTHLY DEVOTED TO THE ORGAN AND THE INTERESTS OF ORGANISTS Sixty-third Yt'4r, No . 5 - WIIDIt: No. 749 SUIIScril'tiOJJS $-tOCl a year - 40 cellts n copy .JJarolJ qlecuon GilJ~liel~ r&rl~Ja'l 5ritule THE DIAPASON Congl'atutatioTUJ to (x............. , ••/Mr. aI U. S. P....., 01/1.. ) s. E. CRUENSTEIN. PUWWO., (1808-1857) on RONIT SCHUNIMAN APRIL. 1972 frllto, FEAT1IIIES DOIOtHY 1050 Some Sp.c:ulatiaDS Coacemlng the 'ulin... Manag., Inslrumeatal Mualc 01 the Faerua Codex 117 Dr W. Thoma Marrocco & WISl!Y vas Roberl Hu.. tIa 3. 11. 17. 11 AaI"an' ErIl,o, Adam 01 Fulda: TJa.an.1 and This issue of TilE DIArAsoN is dedicated to a man who ha.s 3.chievcd distinc Compol.r tion in the fields of organ instruction. organ lih'raturc and history, organ build Ir Lewis Rowen 4. S. 20 ing. and musicology. but cspt."CiaIly as a pedagf'llgue. The countless number of An l",emGlional Month,., Deao,.d '0 students now holding responsible positions in our colleges and universities allests 'h. Or,n aM '0 Or,.tau and to his skill in teaching. CII..,eI, Mule A Concert On)'Ga lor Rayce HaD. V.C.L.A. Harold Cleason was oorn in Jctrt.' TWU. Ohio, on April ~W . 1892. but rt.'Ccivet) Iy Robert L. Tual., I. 1. 22. 13 his schooling in l'as.1dctl3, first :It the Throop l'uillCdlllic Institute and later at Official JourrNJ/ .J ,h. the California Institute of T t."t hnnlogy. At the age of 20 he realiu'tl that his lo\'c Dmo. -

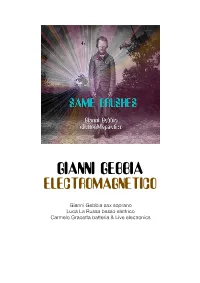

Elettromagnetico 3 Pres It. Copia

GIANNI GEBBIA ELECTROMAGNETICO Gianni Gebbia sax soprano Luca La Russa basso elettrico Carmelo Graceffa batteria & Live electronics Il noto sassofonista e compositore siciliano Gianni Gebbia ha creato questo nuovo trio elettrico nel 2016 con lo scopo di concentrarsi sulle proprie composizioni e melodie sviluppate in un lunghissimo arco di tempo dai primi anni 80 ad oggi attraversando le esperienze musicali più disparate : dal folk alla world music, dai gruppi prog anni 70 all’improvvisazione radicale al jazz contemporaneo. In elettromagnetico vi è una speciale attenzione sui moduli ipnotici e ripetitivi accanto allo sviluppo di melodie derivanti dalla tradizione musicale delle isole del mediterraneo ma anche elementi influenze come i Magma, Wayne Shorter, Nucleus, Deerhoof. Lo accompagnano in questa ricerca il bassista Luca La Russa ed il batterista Carmelo Graceffa due giovani e solidi musicisti che supportano e sviluppano le idee del saxofonista con grande intensità. Gianni Gebbia utilizza la respirazione circolare della quale è considerato uno dei massimi esploratori come metodo elettivo per creare questo climax magnetico ed ipnotico che ci porta in un viaggio che parte dai cantori ignoti delle strade di Palermo ai maestri sardi delle launeddas sino alle sonorità di uno Steve Lacy.Nel Luglio 2016 hanno inciso il loro primo album per l’etichetta objet-a dal titolo “ Same Brushes “. Il Trio elettromagnetico ha già compiuto un primo tour europeo ed ha partecipato al rock festival Pas de Trai 2016, Levanzo Community Fest e al prestigioso Festiwall 2016 a Ragusa una delle massime rassegne al mondo di street painting. A settembre del 2016 Il brano Lynx è stato inserito come download of the day dalla rivista online Allaboutjazz.com/usa raggiungendo migliaia di ascolti.