I PERCY GRAINGER's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Symphonic Band 2012–13 Season Sunday 21 October 2012 83Rd Concert Miller Auditorium 3:00 P.M

University Symphonic Band 2012–13 Season Sunday 21 October 2012 83rd Concert Miller Auditorium 3:00 p.m. ROBERT SPRADLING, Conductor Matthew Pagel, Graduate Assistant Conductor Ryan George Firefly (2008) b. 1978 Percy Aldridge Grainger Colonial Song (1911) 1882–1961 Václav Nelhýbel Symphonic Movement (1966) 1919–1996 Matthew Pagel, Conductor Christopher Biggs Object Metamorphosis II (2011) b. 1979 Michael Gandolfi Flourishes and Meditations on a Renaissance Theme (2010) b. 1956 Theme Variation I. (A Cubist Kaleidoscope) Variation II. (Cantus in augumentation: speed demon) Variation III. (Carnival) Variation IV. (Tune’s in the round) Variation V. (Spike) Variation VI. (Rewind/fast forward) Variation VII. (Echoes: a surreal reprise) Building emergencies will be indicated by the flashing exit lights and sounding of alarms within the seating area. Please walk, DO NOT RUN, to the nearest exit. Ushers will be located near exits to assist patrons. Please turn off all cell phones and other electronic devices during the performance. Because of legal issues, any video or audio recording of this performance is prohibited without prior consent from the School of Music. Thank you for your cooperation. PROGRAM NOTES compiled by Robert Spradling and Matthew Pagel George, Firefly the composer’s notes, to be the first in a series of “Sentimentals,” the piece stems from 1905 when Ryan George resides in Austin, Texas and is gaining Grainger was working in London and actively notoriety as a composer and arranger throughout the arranging English folksongs. Between 1913–1928 he United States as well as in Europe and Asia. In produced no fewer than six different arrangements: describing Firefly, George wrote, “I’m amazed at how three for two optional voices with various instrumental children use their imaginations to transform the ensembles; one for piano solo (1921); one for military ordinary into the extraordinary and fantastic. -

Catalogue of Works Barry Peter Ould

Catalogue of Works Barry Peter Ould In preparing this catalogue, I am indebted to Thomas Slattery (The Instrumentalist 1974), Teresa Balough (University of Western Australia 1975), Kay Dreyfus (University of Mel- bourne 1978–95) and David Tall (London 1982) for their original pioneering work in cata- loguing Grainger’s music.1 My ongoing research as archivist to the Percy Grainger Society (UK) has built on those references, and they have greatly helped both in producing cata- logues for the Society and in my work as a music publisher. The Catalogue of Works for this volume lists all Grainger’s original compositions, settings and versions, as well as his arrangements of music by other composers. The many arrangements of Grainger’s music by others are not included, but details may be obtained by contacting the Percy Grainger Society.2 Works in the process of being edited are marked ‡. Key to abbreviations used in the list of compositions Grainger’s generic headings for original works and folk-song settings AFMS American folk-music settings BFMS British folk-music settings DFMS Danish folk-music settings EG Easy Grainger [a collection of keyboard arrangements] FI Faeroe Island dance folk-song settings KJBC Kipling Jungle Book cycle KS Kipling settings OEPM Settings of songs and tunes from William Chappell’s Old English Popular Music RMTB Room-Music Tit Bits S Sentimentals SCS Sea Chanty settings YT Youthful Toneworks Grainger’s generic headings for transcriptions and arrangements CGS Chosen Gems for Strings CGW Chosen Gems for Winds 1 See Bibliography above. 2 See Main Grainger Contacts below. -

Download Booklet

PIANISTS, PSYCHIATRISTS AND PIANO CONCERTOS Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18 “I play all the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order.” That flat-G-C-G, whereas his right could easily encompass C (2nd finger!)-E 1 Moderato 11. 21 2 Adagio sostenuto 12. 03 was how Eric Morecambe answered the taunt of conductor ‘Andrew (thumb)-G-C-E. 3 Allegro scherzando 11. 51 Preview’ (André Previn), who was questioning his rather ‘unusual’ treat- Yet although Rachmaninoff appeared to be a born pianist, he had ment of the introductory theme of Edvard Grieg’s Piano Concerto. set his heart on a career as composer and conductor. Only after fleeing Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) Nowadays, the sketch from the 1971 Christmas show of the famous from Russia following the outbreak of the revolution, did he realise that Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 comedy duo Morecambe and Wise has attained cult status and can be he would not be able to earn a living as a composer, that his lack of tech- 4 Allegro molto moderato 13. 43 viewed on the Internet. Many years later, Previn let slip that taxi-drivers nique would impede a career as a conductor, and that the piano could 5 Adagio 6. 34 still regularly addressed him as ‘Mr Preview’. In fact, the sketch was not well play a much larger role in his life. The many recordings (including 6 Allegro moderato molto e marcato 10. 51 the first to parody Grieg’s indestructible concerto: that honour belongs all his piano concertos and his Paganini Rhapsody) that form a resound- to Franz Reizenstein, with his Concerto Popolare dating from 1959. -

Universiv Micrmlms Internationcil

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microHlming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify m " '<ings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyriglited materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin film ing at the upper le ft hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections w ith small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Seattle Wind Symphony Larry Gookin Conductor & Artistic Director

Seattle Wind Symphony Larry Gookin Conductor & Artistic Director Danny Helseth Assistant Director Jazz Musicians Dr. Daniel Barry (composer) , Steve Mostovoy (trumpet), Javino Santos Neto (piano) performing River of Doubt Beserat Tafesse, Euphonium Soloist, performing Fantasia Di Concerto Saturday February 21st at 7:30 PM Shorewood Performing Arts Center 17300 Fremont Avenue North– Shoreline WA 98133 Larry Gookin has been Director of Bands at Central Washington University since 1981. He has served as the Associate Chair and Coordinator of Graduate Studies. His fields of experse include music educaon, wind literature, conducng, and low brass performance. Professor Gookin received the M.M. in Music Educaon from the University of Oregon School of Music in 1977 and the B.M. in Music Educaon and Trombone Performance from the University of Montana in 1971. He taught band for 10 years in public schools in Montana and Oregon. Prior to accepng the posion as Director of Bands at Central Washington University, he was Director of Bands at South Eugene High School in Eugene, OR. Gookin has served as President of the Northwest Division of the CBDNA, as well as Divisional Chairman for the Naonal Band Associaon. He is past Vice President of the Washington Music Educators Associaon. In 1992, he was elected to the membership of the American Bandmaster’s Associaon, and in 2000 he became a member of the Washington Music Educators “Hall of Fame.” In 2001, Gookin received the Central Washington University Disnguished Professor of Teaching Award, and in 2003 was named WMEA teacher of the year. In 2004, he was selected as Central Washington University’s representave for the Carnegie Foundaon (CASE) teaching award. -

Canzona Peter Mennin Wednesday, October 7, 2015 - 8 P.M

PROGRAM NOTES Mother Earth David Maslanka “Praised be You, my Lord, for our sister, Mother Earth, Who nourishes us and teaches us. Bringing forth all kinds of fruits and colored flowers and herbs.” WIND ENSEMBLE -St. Francis of Assisi Eddie R. Smith, conductor Canzona Peter Mennin Wednesday, October 7, 2015 - 8 p.m. MEMORIAL CHAPEL American composer Peter Mennin chose this title in homage to the Renaissance instrumental forms of that name. Like the canzoni of Gabrieli, this work features Mother Earth David Maslanka contrasting, antiphonal statements from opposing voices; Mennin has combined (b. 1943) that with modern harmony and structure. The work was commissioned in 1950 as part of an effort by Edwin Goldman to develop a significant repertoire for Canzona Peter Mennin concert band. Mennin wrote six symphonies, concertos, sonatas and choral works. (1923-1983) Canzona is the only piece he wrote for concert band. David Moreland, conductor Variants on a Mediaeval Tune Norman Dello Joio Variants on a Mediaeval Tune Norman Dello Joio “In dulci jubilo” is a melody which has been used by many composers. Dello Joio Andante moderato (1913-2008) was inspired by it to compose a set of variations consisting of a brief introduction Allegro deciso and theme follow by five “variants” which send the mediaeval melody through five Lento, pesante true metamorphoses contrasting in tempo and character. Allegro spumante Andante French Impressions Guy Woolfenden Allegro gioioso “This work is inspired by four paintings by the French painter Georges Seurat French Impressions Guy Woolfenden (1859-1891), but do not attempt to recreate his pointillist technique in musical Parade (b. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

Advanced Conducting Project

Messiah University Mosaic Conducting Student Scholarship Music conducting 2017 Advanced Conducting Project Jared M. Daubert Messiah College Follow this and additional works at: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/conduct_st Part of the Music Commons Permanent URL: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/conduct_st/11 Recommended Citation Daubert, Jared M., "Advanced Conducting Project" (2017). Conducting Student Scholarship. 11. https://mosaic.messiah.edu/conduct_st/11 Sharpening Intellect | Deepening Christian Faith | Inspiring Action Messiah University is a Christian university of the liberal and applied arts and sciences. Our mission is to educate men and women toward maturity of intellect, character and Christian faith in preparation for lives of service, leadership and reconciliation in church and society. www.Messiah.edu One University Ave. | Mechanicsburg PA 17055 Running head: MUAP 504 ADVANCED CONDUCTING PROJECT 1 MUAP 504 Advanced Conducting Project Jared M. Daubert Messiah College MUAP 504 ADVANCED CONDUCTING PROJECT 2 Table of Contents Abracadabra……………………………………………………………………………………..3 Arabian Dances…………………………………………………………………………….….18 Country Wildflowers…………………………………………………………………………...29 Sinfonia for Winds……………………………………………………………………………..39 Third Suite………………………………………………………………...……………………49 References……………………………………………………………………………………..68 MUAP 504 ADVANCED CONDUCTING PROJECT 3 Abracadabra Frank Ticheli (b. 1958) Unit 1: Composer Dr. Frank Ticheli earned a Bachelor of Music from Southern Methodist University in 1981. He completed a Master in Music in 1983 and -

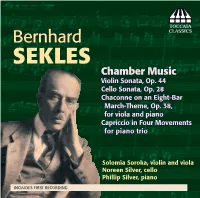

Toccata Classics TOCC0147 Notes

TOCCATA Bernhard CLASSICS SEKLES Chamber Music Violin Sonata, Op. 44 Cello Sonata, Op. 28 Chaconne on an Eight-Bar March-Theme, Op. 38, for viola and piano ℗ Capriccio in Four Movements for piano trio Solomia Soroka, violin and viola Noreen Silver, cello Phillip Silver, piano INCLUDES FIRST RECORDING REDISCOVERING BERNHARD SEKLES by Phillip Silver he present-day obscurity of Bernhard Sekles illustrates how porous is contemporary knowledge of twentieth-century music: during his lifetime Sekles was prominent as teacher, administrator and composer alike. History has accorded him footnote status in two of these areas of endeavour: as an educator with an enviable list of students, and as the Director of the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt from 923 to 933. During that period he established an opera school, much expanded the area of early-childhood music-education and, most notoriously, in 928 established the world’s irst academic class in jazz studies, a decision which unleashed a storm of controversy and protest from nationalist and fascist quarters. But Sekles was also a composer, a very good one whose music is imbued with a considerable dose of the unexpected; it is traditional without being derivative. He had the unenviable position of spending the prime of his life in a nation irst rent by war and then enmeshed in a grotesque and ultimately suicidal battle between the warring political ideologies that paved the way for the Nazi take-over of 933. he banning of his music by the Nazis and its subsequent inability to re-establish itself in the repertoire has obscured the fact that, dating back to at least 99, the integration of jazz elements in his works marks him as one of the irst European composers to use this emerging art-form within a formal classical structure. -

Otto Klemperer Curriculum Vitae

Dick Bruggeman Werner Unger Otto Klemperer Curriculum vitae 1885 Born 14 May in Breslau, Germany (since 1945: Wrocław, Poland). 1889 The family moves to Hamburg, where the 9-year old Otto for the first time of his life spots Gustav Mahler (then Kapellmeister at the Municipal Theatre) out on the street. 1901 Piano studies and theory lessons at the Hoch Conservatory, Frankfurt am Main. 1902 Enters the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory in Berlin. 1905 Continues piano studies at Berlin’s Stern Conservatory, besides theory also takes up conducting and composition lessons (with Hans Pfitzner). Conducts the off-stage orchestra for Mahler’s Second Symphony under Oskar Fried, meeting the composer personally for the first time during the rehearsals. 1906 Debuts as opera conductor in Max Reinhardt’s production of Offenbach’s Orpheus in der Unterwelt, substituting for Oskar Fried after the first night. Klemperer visits Mahler in Vienna armed with his piano arrangement of his Second Symphony and plays him the Scherzo (by heart). Mahler gives him a written recommendation as ‘an outstanding musician, predestined for a conductor’s career’. 1907-1910 First engagement as assistant conductor and chorus master at the Deutsches Landestheater in Prague. Debuts with Weber’s Der Freischütz. Attends the rehearsals and first performance (19 September 1908) of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony. 1910 Decides to leave the Jewish congregation (January). Attends Mahler’s rehearsals for the first performance (12 September) of his Eighth Symphony in Munich. 1910-1912 Serves as Kapellmeister (i.e., assistant conductor, together with Gustav Brecher) at Hamburg’s Stadttheater (Municipal Opera). Debuts with Wagner’s Lohengrin and conducts guest performances by Enrico Caruso (Bizet’s Carmen and Verdi’s Rigoletto). -

Lincolnshire Posy Abbig

A Historical and Analytical Research on the Development of Percy Grainger’s Wind Ensemble Masterpiece: Lincolnshire Posy Abbigail Ramsey Stephen F. Austin State University, Department of Music Graduate Research Conference 2021 Dr. David Campo, Advisor April 13, 2021 Ramsey 1 Introduction Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy has become a staple of wind ensemble repertoire and is a work most professional wind ensembles have performed. Lincolnshire Posy was composed in 1937, during a time when the wind band repertoire was not as developed as other performance media. During his travels to Lincolnshire, England during the early 20th century, Grainger became intrigued by the musical culture and was inspired to musically portray the unique qualities of the locals that shared their narrative ballads through song. While Grainger’s collection efforts occurred in the early 1900s, Lincolnshire Posy did not come to fruition until it was commissioned by the American Bandmasters Association for their 1937 convention. Grainger’s later relationship with Frederick Fennell and Fennell’s subsequent creation of the Eastman Wind Ensemble in 1952 led to the increased popularity of Lincolnshire Posy. The unique instrumentation and unprecedented performance ability of the group allowed a larger audience access to this masterwork. Fennell and his ensemble’s new approach to wind band performance allowed complex literature like Lincolnshire Posy to be properly performed and contributed to establishing wind band as a respected performance medium within the greater musical community. Percy Grainger: Biography Percy Aldridge Grainger was an Australian-born composer, pianist, ethnomusicologist, and concert band saxophone virtuoso born on July 8, 1882 in Brighton, Victoria, Australia and died February 20, 1961 in White Plains, New York.1 Grainger was the only child of John Harry Grainger, a successful traveling architect, and Rose Annie Grainger, a self-taught pianist. -

Percy Aldridge Grainger

About Music Celebrations MCI is a full-service concert and festival We are musicians serving musicians organizing company MCI staff has a combined 200+ years John Wiscombe founded MCI in 1993. experience in designing and operating As a youth, he spent several years as a concert tours tour manager throughout Europe. He has now been in the music travel business for over 45 years. Our Staff is composed of a unique blend of musicians and travel industry professionals ...in the folk-song there is to be found the complete history of a people, recorded by the race itself, through the heart outbursts of its healthiest output. It is a history compiled with deeper feeling and more understanding than can be found among the dates and data of the greatest historian... -PERCY ALDRIDGE GRAINGER The 10th annual Percy Grainger Wind Band Festival will feature four outstanding wind ensembles conducting standalone performances of Percy Grainger literature in an afternoon matinee performance in Chicago’s Historic Orchestra Hall at Symphony Center on March 23, 2019. ‘ All band selections are made through Music Celebrations, and every effort will be made to ensure that each ensemble’s program will not overlap onto one another. Ensembles will be accepted on a first-come, first-serve, rolling basis. Early applicants are given preference and priority. Mallory Thompson is director of bands, professor of music, coordinator of the conducting program, and holds the John W. Beattie Chair of Music at Northwestern University. In 2003 she was named a Charles Deering McCormick Professor of Teaching Excellence. As the third person in the university's history to hold the director of bands position, Dr.