Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: a Study of Traditions and Influences

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2012 Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences Sara Gardner Birnbaum University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Birnbaum, Sara Gardner, "Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

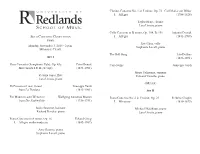

University Symphonic Band 2012–13 Season Sunday 21 October 2012 83Rd Concert Miller Auditorium 3:00 P.M

University Symphonic Band 2012–13 Season Sunday 21 October 2012 83rd Concert Miller Auditorium 3:00 p.m. ROBERT SPRADLING, Conductor Matthew Pagel, Graduate Assistant Conductor Ryan George Firefly (2008) b. 1978 Percy Aldridge Grainger Colonial Song (1911) 1882–1961 Václav Nelhýbel Symphonic Movement (1966) 1919–1996 Matthew Pagel, Conductor Christopher Biggs Object Metamorphosis II (2011) b. 1979 Michael Gandolfi Flourishes and Meditations on a Renaissance Theme (2010) b. 1956 Theme Variation I. (A Cubist Kaleidoscope) Variation II. (Cantus in augumentation: speed demon) Variation III. (Carnival) Variation IV. (Tune’s in the round) Variation V. (Spike) Variation VI. (Rewind/fast forward) Variation VII. (Echoes: a surreal reprise) Building emergencies will be indicated by the flashing exit lights and sounding of alarms within the seating area. Please walk, DO NOT RUN, to the nearest exit. Ushers will be located near exits to assist patrons. Please turn off all cell phones and other electronic devices during the performance. Because of legal issues, any video or audio recording of this performance is prohibited without prior consent from the School of Music. Thank you for your cooperation. PROGRAM NOTES compiled by Robert Spradling and Matthew Pagel George, Firefly the composer’s notes, to be the first in a series of “Sentimentals,” the piece stems from 1905 when Ryan George resides in Austin, Texas and is gaining Grainger was working in London and actively notoriety as a composer and arranger throughout the arranging English folksongs. Between 1913–1928 he United States as well as in Europe and Asia. In produced no fewer than six different arrangements: describing Firefly, George wrote, “I’m amazed at how three for two optional voices with various instrumental children use their imaginations to transform the ensembles; one for piano solo (1921); one for military ordinary into the extraordinary and fantastic. -

Syphilis' Impact on Late Works of Classical Music Composers

SYPHILIS’ IMPACT ON LATE WORKS OF CLASSICAL MUSIC COMPOSERS Rempelakos L1, Poulakou-Rebelakou E1, Tsiamis C1, Rempelakos A2 1History of Medicine, Athens University Medical School, Athens, Greece 2Urologic Department, Hippocrateion Hospital, Athens, Greece INTRODUCTION & OBJECTIVE: To present the effects of the tertiary stage syphilis on the last works of some famous European classical music composers who suffered from the disease. METHODS: The review of the biographies of seven documented syphilis cases of composers, focusing on the events of their last period of life and the review of the critics for their artistic expression under disease-affected circumstances. RESULTS: The 19th century is undeniably considered as the golden age of classical music but, at the same time, some of the most famous composers were victims of this disease-menace, strongly stigmatizing themselves and their families, the latter trying to keep the shameful secret, aftermath destructing sources and documents. Seven cases of musicians with syphilis have been studied: Franz Schubert died at the age of 31, while Robert Schumann and Hugo Wolf (age at death 46 and 43 respectively), both attempted suicide and passed the rest of their lives in insane asylums. Moreover, Gaetano Donizetti infected his wife, Virginia, who died in childbirth before his own death occurring between catatonic symptoms and bouts of persecution mania. Bedrich Smetana predicted his death entitling his composition “final page” and indeed, he did not compose anymore and died soon in a mental asylum. Frederick Delius lived for fifteen years blind and paralyzed dictating his scores to a young follower of his music, although the quality of the late compositions cannot be compared with the priors. -

In Concert AUGUST–SEPTEMBER 2012

ABOUT THE MUSIC GRIEG CONCERTO /IN CONCERT AUGUST–SEPTEMBER 2012 GRIEG CONCERTO 30 AUGUST–1 SEPTEMBER STEPHEN HOUGH PLAYS TCHAIKOVSKY 14, 15 AND 17 SEPTEMBER TCHAIKOVSKY’S PATHÉTIQUE 20–22 SEPTEMBER ENIGMA VARIATIONS 28 SEPTEMBER MEET YOUR MSO MUSICIANS: SYLVIA HOSKING AND MICHAEL PISANI PIERS LANE VISITS GRIEG’S BIRTHPLACE STEPHEN HOUGH ON TCHAIKOVSKY’S PIANO CONCERTO NO.2 SIR ANDREW DAVIS HAILS THE NEW HAMER HALL twitter.com/melbsymphony facebook.com/melbournesymphony IMAGE: SIR ANDREW Davis CONDUCTING THE MELBOURNE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Download our free app 1 from the MSO website. www.mso.com.au/msolearn THE SPONSORS PRINCIPAL PARTNER MSO AMBASSADOR Geoffrey Rush GOVERNMENT PARTNERS MAESTRO PARTNER CONCERTMASTER PARTNERS MSO POPS SERIES REGIONAL TOURING PRESENTING PARTNER PARTNER ASSOCIATE PARTNERS SUPPORTING PARTNERS MONASH SERIES PARTNER SUPPLIERS Kent Moving and Storage Quince’s Scenicruisers Melbourne Brass and Woodwind Nose to Tail WELCOME Ashton Raggatt McDougall, has (I urge you to read his reflections been reported all over the world. on Grieg’s Concerto on page 16) and Stephen Hough, and The program of music by Grieg conductors Andrew Litton and and his friend and champion HY Christopher Seaman, the last of Percy Grainger that I have the whom will be joined by two of the privilege to conduct from August finest brass soloists in the world, otograp 29 to September 1 will be a H P Radovan Vlatkovic (horn) and wonderful opportunity for you to ta S Øystein Baadsvik (tuba), for our O experience all the richness our C special Town Hall concert at the A “new” hall has to offer. -

Journal81-1.Pdf

January 1984, Number 81 The Delius Society Journal The Delius Society Journal-_._- January 1984, Number 818l The Delius Society Full Membership £8.00f,8.00 per year Students £5.0095.00 Subscription to Libraries (Journal only) £6.00f,6.00 per year USA and Canada US $17.00 per year President Eric Fenby OBE, Hon DMus,D Mus, Hon DLitt,D Litt, Hon RAM Vice Presidents The Rt Hon Lord Boothby KBE, LLD Felix Aprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson M Sc, Ph D (Founder Member) Sir Charles Groves CBE Stanford Robinson OBE, ARCM (Hon), Hon CSM Meredith Davies CBE, MA, BMus,B Mus, FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE, Hon DMusD Mus YemonVernon Handley MA, FRCM·,FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Chairman RBR B Meadows 5 Westbourne House, Mount Park Road, Harrow, Middlesex Treasurer Peter Lyons 160 Wishing Tree Road, St. Leonards-on-Sea, East Sussex Secretary Miss Diane Eastwood 28 Emscote Street South, Bell Hall, Halifax, Yorkshire Tel: (0422) 5053750537 Editor Stephen Lloyd 41 Marlborough Road, Luton, Bedfordshire LU3 lEFIEF Tel: Luton (0582)(0582\ 2007520075 2 Contents Editorial . .33 lamesJamesFarrar: Poet, Airman and Delian by Christopher PalmerPalmer. .4 LeslieLeslieHewardbyLyndonJenkinsHeward by Lyndon lenkins .....1313 Fennimore and Gerda at the Edinburgh Festival by Gordon LovgreenIovgreen. .1616 Correspondence .....212] ForthcomingForthcomingEventsEvents ...2121 Acknowledgements The cover illustration is an early sketch of Delius by Edvard Munch reproduced by kind permission of the Curator of the Munch Museum, Oslo. The two photographic plates in this issue have been financed by a legacy to the Delius Society from the late Robert Aickman. ISSN 0306 0373 3 Editorial Perhaps the most keenly anticipated event to have occurred within the past three months has been the publication of Lionel Carley's Delius: A Life in Letters 1862-19081862-1908 (Scolar Press, £25). -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

Catalogue of Works Barry Peter Ould

Catalogue of Works Barry Peter Ould In preparing this catalogue, I am indebted to Thomas Slattery (The Instrumentalist 1974), Teresa Balough (University of Western Australia 1975), Kay Dreyfus (University of Mel- bourne 1978–95) and David Tall (London 1982) for their original pioneering work in cata- loguing Grainger’s music.1 My ongoing research as archivist to the Percy Grainger Society (UK) has built on those references, and they have greatly helped both in producing cata- logues for the Society and in my work as a music publisher. The Catalogue of Works for this volume lists all Grainger’s original compositions, settings and versions, as well as his arrangements of music by other composers. The many arrangements of Grainger’s music by others are not included, but details may be obtained by contacting the Percy Grainger Society.2 Works in the process of being edited are marked ‡. Key to abbreviations used in the list of compositions Grainger’s generic headings for original works and folk-song settings AFMS American folk-music settings BFMS British folk-music settings DFMS Danish folk-music settings EG Easy Grainger [a collection of keyboard arrangements] FI Faeroe Island dance folk-song settings KJBC Kipling Jungle Book cycle KS Kipling settings OEPM Settings of songs and tunes from William Chappell’s Old English Popular Music RMTB Room-Music Tit Bits S Sentimentals SCS Sea Chanty settings YT Youthful Toneworks Grainger’s generic headings for transcriptions and arrangements CGS Chosen Gems for Strings CGW Chosen Gems for Winds 1 See Bibliography above. 2 See Main Grainger Contacts below. -

Seattle Wind Symphony Larry Gookin Conductor & Artistic Director

Seattle Wind Symphony Larry Gookin Conductor & Artistic Director Danny Helseth Assistant Director Jazz Musicians Dr. Daniel Barry (composer) , Steve Mostovoy (trumpet), Javino Santos Neto (piano) performing River of Doubt Beserat Tafesse, Euphonium Soloist, performing Fantasia Di Concerto Saturday February 21st at 7:30 PM Shorewood Performing Arts Center 17300 Fremont Avenue North– Shoreline WA 98133 Larry Gookin has been Director of Bands at Central Washington University since 1981. He has served as the Associate Chair and Coordinator of Graduate Studies. His fields of experse include music educaon, wind literature, conducng, and low brass performance. Professor Gookin received the M.M. in Music Educaon from the University of Oregon School of Music in 1977 and the B.M. in Music Educaon and Trombone Performance from the University of Montana in 1971. He taught band for 10 years in public schools in Montana and Oregon. Prior to accepng the posion as Director of Bands at Central Washington University, he was Director of Bands at South Eugene High School in Eugene, OR. Gookin has served as President of the Northwest Division of the CBDNA, as well as Divisional Chairman for the Naonal Band Associaon. He is past Vice President of the Washington Music Educators Associaon. In 1992, he was elected to the membership of the American Bandmaster’s Associaon, and in 2000 he became a member of the Washington Music Educators “Hall of Fame.” In 2001, Gookin received the Central Washington University Disnguished Professor of Teaching Award, and in 2003 was named WMEA teacher of the year. In 2004, he was selected as Central Washington University’s representave for the Carnegie Foundaon (CASE) teaching award. -

The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2016, Number 160

The Delius Society Journal Autumn 2016, Number 160 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No 298662) President Lionel Carley BA, PhD Vice Presidents Roger Buckley Sir Andrew Davis CBE Sir Mark Elder CBE Bo Holten RaD Piers Lane AO, Hon DMus Martin Lee-Browne CBE David Lloyd-Jones BA, FGSM, Hon DMus Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Anthony Payne Website: delius.org.uk ISSN-0306-0373 THE DELIUS SOCIETY Chairman Position vacant Treasurer Jim Beavis 70 Aylesford Avenue, Beckenham, Kent BR3 3SD Email: [email protected] Membership Secretary Paul Chennell 19 Moriatry Close, London N7 0EF Email: [email protected] Journal Editor Katharine Richman 15 Oldcorne Hollow, Yateley GU46 6FL Tel: 01252 861841 Email: [email protected] Front and back covers: Delius’s house at Grez-sur-Loing Paintings by Ishihara Takujiro The Editor has tried in good faith to contact the holders of the copyright in all material used in this Journal (other than holders of it for material which has been specifically provided by agreement with the Editor), and to obtain their permission to reproduce it. Any breaches of copyright are unintentional and regretted. CONTENTS EDITORIAL ..........................................................................................................5 COMMITTEE NOTES..........................................................................................6 SWEDISH CONNECTIONS ...............................................................................7 DELIUS’S NORWEGIAN AND DANISH SONGS: VEHICLES OF -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st.