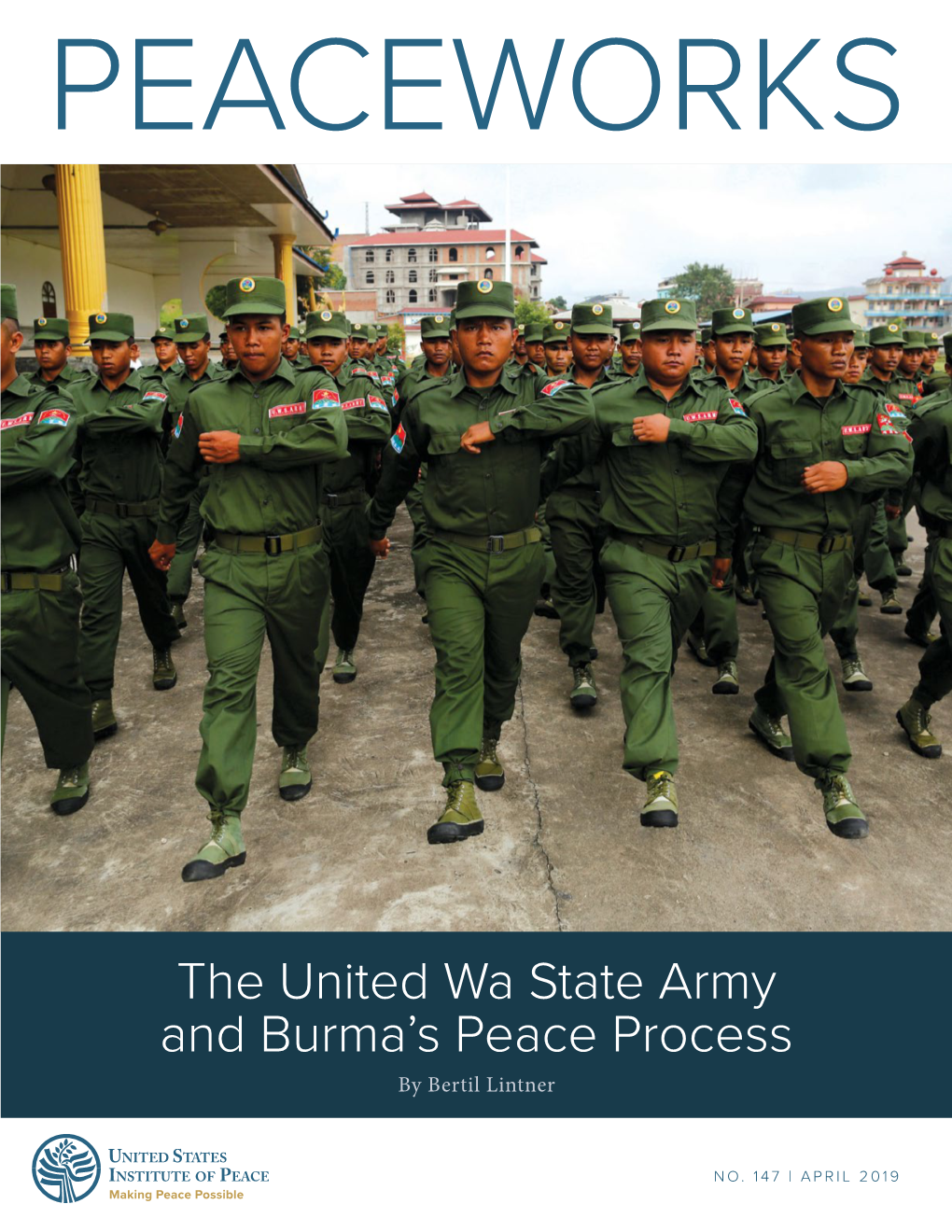

The United Wa State Army and Burma's Peace Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gold Mining in Shwegyin Township, Pegu Division (Earthrights International)

Accessible Alternatives Ethnic Communities’ Contribution to Social Development and Environmental Conservation in Burma Burma Environmental Working Group September 2009 CONTENTS Acknowledgments ......................................................................................... iii About BEWG ................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ...................................................................................... v Notes on Place Names and Currency .......................................................... vii Burma Map & Case Study Areas ................................................................. viii Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 Arakan State Cut into the Ground: The Destruction of Mangroves and its Impacts on Local Coastal Communities (Network for Environmental and Economic Development - Burma) ................................................................. 2 Traditional Oil Drillers Threatened by China’s Oil Exploration (Arakan Oil Watch) ........................................................................................ 14 Kachin State Kachin Herbal Medicine Initiative: Creating Opportunities for Conservation and Income Generation (Pan Kachin Development Society) ........................ 33 The Role of Kachin People in the Hugawng Valley Tiger Reserve (Kachin Development Networking Group) ................................................... 44 Karen -

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin minorityrights.org/minorities/kachin/ June 19, 2015 Profile The Kachin encompass a number of ethnic groups speaking almost a dozen distinct languages belonging to the Tibeto-Burman linguistic family who inhabit the same region in the northern part of Burma on the border with China, mainly in Kachin State. Strictly speaking, these languages are not necessarily closely related, and the term Kachin at times is used to refer specifically to the largest of the groups (the Kachin or Jingpho/Jinghpaw) or to the whole grouping of Tibeto-Burman speaking minorities in the region, which include the Maru, Lisu, Lashu, etc. The exact Kachin population is unknown due to the absence of reliable census data in Burma for more than 60 years. Most estimates suggest there may in the vicinity of 1 million Kachin in the country. The Kachin, as well as the Chin, are one of Burma’s largest Christian minorities: though once again difficult to assess, it is generally thought that between two-thirds and 90 per cent of Kachin are Christians, with others following animist practices or Buddhists. Historical context It is generally thought that the Kachin gradually moved south from their ancestral land on the Tibetan plateau through Yunnan in southern China to arrive in the northern region of what would become Burma sometime during the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, making the Kachin relative newcomers. Their position in this borderland part of South-East Asia meant that the Kachin were often outside of the sphere of influence of Burman kings. Their strength was such by the Third Anglo-Burmese War of 1885 that, while the British were taking Mandalay, the Kachin were getting ready to take advantage of the Burman kingdom’s weakness to attack and take over Mandalay themselves. -

A Short Outline of the History of the Communist Party of Burma

A SHORT OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF .· THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF BURMA I Burma was an independent kingdom before annexation by the British imperialist in 1824. In 1885 British imperialist annexed whole of Burma. Since that time, Burmese people have never given up their fight for regaining their independence. Various armed uprisings and other legal forms of strug gle were used by the Burmese people in their fight to regain indep~ndence. In 19~8 the biggest and the broadest anti-British general _strike over-ran the whole country. The workers were on strike, the peasants marched up to Rangoon and all the students deserted their class-room to join the workers and peasants. It was an unprecendented anti-British movement in Burma popularly called in Burmese as "1300th movement". Out of this national and class struggle of the Burmese people and working class emerges the Communist Party of Burma. II The Communist Party of Burma was of!i~ially founded on 15th ~_!l_g~s_b 1939 by _!!nitil)K all MarxisLgr.9J!l!§ in Burma, III From the day of inception, CPB launched an active anti-British struggles up till 1941. It was the core of CPB leadership that led ahti British struggles up till the second world war. IV In 1941, after the Hitlerites treacherously attacked the Soviet Union, CPB changed its tactics and directed its blows against the fascists. v In 1942, Burma was invaded by the Japanese fascists. From that time onwards up till 1945, CPB worked unt~ringly to oppose the Japanese fa~ists 1 . -

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics acleddata.com/2018/07/21/analysis-of-the-fpncc-northern-alliance-and-myanmar-conflict-dynamics/ Elliott Bynum July 21, 2018 With the Myanmar military pressuring all ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), non-signatory EAOs have responded by forming a loose military alliance, called the Northern Alliance, to strengthen their position against the military. As with many alliances in Myanmar’s history, the cohesiveness and long-term viability of the alliance is uncertain. Increased military operations by the Myanmar military against the groups in this alliance, particularly the increased use of remote violence, has resulted in the alliance groups shifting their tactics both politically and militarily. In 2016, four EAOs formed the Northern Alliance. The driver behind the formation of the Northern Alliance was the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) which has been in conflict with the Myanmar military for several decades. From 1994-2011, the KIA had a bilateral ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar military which held. The conflict reignited in 2011 after the KIA rejected the military’s Border Guard Force (BGF) scheme which would have placed the KIA under the control of the military. At the time, the Myanmar military also had increased its presence in the Kachin region to guard the Chinese construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam which exacerbated tensions, leading eventually to the start of the current war. The KIA has since sought to strengthen its position by providing training and support to the Arakan Army (AA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). -

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team Seventeen Ethnic Armed Organizations held a conference in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO/KIA on 30 Oct – 2 Nov 2013. At the end of the conference, ethnic leaders established Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT) on Nov 2, 2013. The NCCT will represent to member ethnic armed organizations when negotiating with government peace negotiation team, UPWC. NCCT Leader: • Vice-Chairman : Nai Hong Sar, New Mon State Party • Deputy Leader 1 : General Secretary – Padoh Kwe Htoo Win (Karen National Union) • Deputy Leader 2 : Deputy Commander-in-Chief – Maj. Gen. Gun Maw (KIA) Member • Lt. Col. Kyaw Han, Arakan Army • Central Committee Member Ms. Mra Raza Lin, Arakan Liberation Party • General Secretary Twan Zaw, Arakan National Council • Presidium Dr. Lian Sakhong, Chin National Front • Col. Saw Lont Lon, Democratic Karen Benevolent Army • Secretary-2 Shwe Myo Thant, Karenni National Progressive Party • Gen. Dr. Timothy, Foreign Affairs, KNU/KNLA Peace Council • Col. Hkun Okker, Patron, Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization • Central Committee member Sai Ba Tun, Shan State Progress Party • Secretary-General Ta Aik Nyunt, Wa National Organization NCCT member Organizations: 1. Arakan Liberation Party 2. Arakan National Council 3. Arakan Army 4. Chin National Front 5. Democratic Karen Benevolent Army 6. Karenni National Progressive Party 7. Chairman, Karen National Union 8. KNU/KNLA Peace Council 9. Lahu Democratic Union 10. Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army 11. New Mon State Party 12. Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization 13. Palaung State Liberation Front 14. Shan State Progress Party 15. Wa National Organiztion 16. Kachin Independence Organization Note: Representatives of Restoration Council of Shan State attended the ethnic armed organizations conference held in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO. -

Drug Trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle

Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy To cite this version: Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy. Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle. An Atlas of Trafficking in Southeast Asia. The Illegal Trade in Arms, Drugs, People, Counterfeit Goods and Natural Resources in Mainland, IB Tauris, p. 1-32, 2013. hal-01050968 HAL Id: hal-01050968 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01050968 Submitted on 25 Jul 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Atlas of Trafficking in Mainland Southeast Asia Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy CNRS-Prodig (Maps 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 25, 31) The Golden Triangle is the name given to the area of mainland Southeast Asia where most of the world‟s illicit opium has originated since the early 1950s and until 1990, before Afghanistan‟s opium production surpassed that of Burma. It is located in the highlands of the fan-shaped relief of the Indochinese peninsula, where the international borders of Burma, Laos, and Thailand, run. However, if opium poppy cultivation has taken place in the border region shared by the three countries ever since the mid-nineteenth century, it has largely receded in the 1990s and is now confined to the Kachin and Shan States of northern and northeastern Burma along the borders of China, Laos, and Thailand. -

Arakan Army, AA)

Division de l’information, de la documentation et des recherches – DIDR 9 avril 2021 Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Armée de l’Arakan (Arakan Army, AA) Avertissement Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine, a été élaboré par la DIDR en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière et ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Arakan Army, (AA) Table des matières 1. Principales caractéristiques de l’Arakan Army ................................................................................ 3 1.1. Une organisation liée à la KIA et à l’UWSA ............................................................................. 3 1.2. Relations avec les autres organisations politico-militaires ...................................................... 3 2. Les opérations armées de l’AA ont entraîné des représailles massives ......................................... 4 3. Les interventions de l’AA à des fins logistiques dans les villages ................................................... 5 4. Enlèvements -

Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05k6p059 Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 10(2) Author Guyon, Rudy Publication Date 1992 DOI 10.5070/P8102021999 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California COMMENTS VIOLENT REPRESSION IN BURMA: HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE GLOBAL RESPONSE Rudy Guyont TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................ 410 I. SLORC AND THE REPRESSION OF THE DEMOCRACY MOVEMENT ....................... 412 A. Burma: A Troubled History ..................... 412 B. The Pro-Democracy Rebellion and the Coup to Restore Military Control ......................... 414 C. Post Coup Elections and Political Repression ..... 417 D. Legalizing Repression ........................... 419 E. A Country Rife with Poverty, Drugs, and War ... 421 II. HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN BURMA ........... 424 A. Murder and Summary Execution ................ 424 B. Systematic Racial Discrimination ................ 425 C. Forced Dislocations ............................. 426 D. Prolonged Arbitrary Detention .................. 426 E. Torture of Prisoners ............................. 427 F . R ape ............................................ 427 G . Portering ....................................... 428 H. Environmental Devastation ...................... 428 III. VIOLATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW ....... 428 A. International Agreements of Burma .............. 429 1. The U.N. -

Affirmation of Shan Identities Through Reincarnation and Lineage of the Classical Shan Romantic Legend 'Khun Sam Law'

Thammasat Review 2015, 18(1): 1-26 Affirmation of Shan Identities through Reincarnation and Lineage of the Classical Shan Romantic Legend ‘Khun Sam Law’ Khamindra Phorn Department of Anthropology & Sociology Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University [email protected] Abstract Khun Sam Law–Nang Oo Peim is an 18th-century legend popular among people in all walks of life in Myanmar’s Shan State. To this day, the story is narrated in novels, cartoons, films and songs. If Romeo and Juliet is a classical romance of 16th-century English literature, then Khun Sam Law–Nang Oo Peim, penned by Nang Kham Ku, is the Shan equivalent of William Shakespeare’s masterpiece. Based on this legend, Sai Jerng Harn, a former pop-star, and Sao Hsintham, a Buddhist monk, recast and reimagined the legendary figure as a Shan movement on the one hand, and migrant Shans in Chiang Mai as a Shan Valentine’s celebration and protector of Khun Sam Law lineage on the other. These two movements independently appeared within the Shans communities. This paper seeks to understand how this Shan legend provides a basic source for Shan communities to reimagine and to affirm their identities through the reincarnation and lineage. The pop-star claims to be a reincarnation of Khun Sam Law, while the migrant Shans in Chiang Mai, who principally hail from Kengtawng, claim its lineage continuity. Keywords: Khun Sam Law legend, Khun Sam Law Family, Khun Sam Law movement, Sai Jerng Harn, Sao Hsintham, Kengtawng Thammasat Review 1 Introduction According to Khun Sam Law–Nang Oo Peim, a popular folktale originating in Myanmar’s Shan State, Khun Sam Law was a young merchant from Kengtawng, a small princedom under Mongnai city-state.