7 Publicversion Myanmar Janv2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin minorityrights.org/minorities/kachin/ June 19, 2015 Profile The Kachin encompass a number of ethnic groups speaking almost a dozen distinct languages belonging to the Tibeto-Burman linguistic family who inhabit the same region in the northern part of Burma on the border with China, mainly in Kachin State. Strictly speaking, these languages are not necessarily closely related, and the term Kachin at times is used to refer specifically to the largest of the groups (the Kachin or Jingpho/Jinghpaw) or to the whole grouping of Tibeto-Burman speaking minorities in the region, which include the Maru, Lisu, Lashu, etc. The exact Kachin population is unknown due to the absence of reliable census data in Burma for more than 60 years. Most estimates suggest there may in the vicinity of 1 million Kachin in the country. The Kachin, as well as the Chin, are one of Burma’s largest Christian minorities: though once again difficult to assess, it is generally thought that between two-thirds and 90 per cent of Kachin are Christians, with others following animist practices or Buddhists. Historical context It is generally thought that the Kachin gradually moved south from their ancestral land on the Tibetan plateau through Yunnan in southern China to arrive in the northern region of what would become Burma sometime during the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, making the Kachin relative newcomers. Their position in this borderland part of South-East Asia meant that the Kachin were often outside of the sphere of influence of Burman kings. Their strength was such by the Third Anglo-Burmese War of 1885 that, while the British were taking Mandalay, the Kachin were getting ready to take advantage of the Burman kingdom’s weakness to attack and take over Mandalay themselves. -

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics acleddata.com/2018/07/21/analysis-of-the-fpncc-northern-alliance-and-myanmar-conflict-dynamics/ Elliott Bynum July 21, 2018 With the Myanmar military pressuring all ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), non-signatory EAOs have responded by forming a loose military alliance, called the Northern Alliance, to strengthen their position against the military. As with many alliances in Myanmar’s history, the cohesiveness and long-term viability of the alliance is uncertain. Increased military operations by the Myanmar military against the groups in this alliance, particularly the increased use of remote violence, has resulted in the alliance groups shifting their tactics both politically and militarily. In 2016, four EAOs formed the Northern Alliance. The driver behind the formation of the Northern Alliance was the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) which has been in conflict with the Myanmar military for several decades. From 1994-2011, the KIA had a bilateral ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar military which held. The conflict reignited in 2011 after the KIA rejected the military’s Border Guard Force (BGF) scheme which would have placed the KIA under the control of the military. At the time, the Myanmar military also had increased its presence in the Kachin region to guard the Chinese construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam which exacerbated tensions, leading eventually to the start of the current war. The KIA has since sought to strengthen its position by providing training and support to the Arakan Army (AA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). -

5-Year Strategic Development Plan, 2018-2022 Pa-O Self-Administered Zone Shan State, Republic of the Union of Myanmar

5-Year Strategic Development Plan, 2018-2022 Pa-O Self-Administered Zone Shan State, Republic of the Union of Myanmar A PROSPEROUS COMMUNITY FOR THIS AND FUTURE VOLUME II: DEVELOPMENT PROPOSALS GENERATIONS Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development 12, Kanbawza Street, Bahan Township Yangon, Myanmar [email protected] | www.mmiid.org Author | Paul Knipe Contributors | Victoria Garcia, Mike Haynes, U Yae Htut, Qingrui Huang, Jolanda Jonkhart, Joern Kristensen, Daw Khin Yupar Kyaw, U Ko Lwin, Daw Hsu Myat Myint Lwin, U Myint Lwin, Daw Thet Htar Myint, U Nay Linn Oo, Samuel Pursch, Barbara Schott, Dr Khin Thawda Shein, U Kyaw Thein, Daw Nilar Win Yangon, August 2018 Cover image | Participant from the Pa-O Women’s Union at the Evaluation and Strategy Workshop TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations .........................................................................................................................I Map of the Pa-O SAZ ..........................................................................................................II Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1 1. Infrastructure ...................................................................................................................2 Map 1: Hopong Township village road upgrade ...................................................3 Map 2: Hsihseng Township village road upgrade ................................................4 Map 3: Pinlaung Township village road upgrade .................................................5 -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team Seventeen Ethnic Armed Organizations held a conference in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO/KIA on 30 Oct – 2 Nov 2013. At the end of the conference, ethnic leaders established Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT) on Nov 2, 2013. The NCCT will represent to member ethnic armed organizations when negotiating with government peace negotiation team, UPWC. NCCT Leader: • Vice-Chairman : Nai Hong Sar, New Mon State Party • Deputy Leader 1 : General Secretary – Padoh Kwe Htoo Win (Karen National Union) • Deputy Leader 2 : Deputy Commander-in-Chief – Maj. Gen. Gun Maw (KIA) Member • Lt. Col. Kyaw Han, Arakan Army • Central Committee Member Ms. Mra Raza Lin, Arakan Liberation Party • General Secretary Twan Zaw, Arakan National Council • Presidium Dr. Lian Sakhong, Chin National Front • Col. Saw Lont Lon, Democratic Karen Benevolent Army • Secretary-2 Shwe Myo Thant, Karenni National Progressive Party • Gen. Dr. Timothy, Foreign Affairs, KNU/KNLA Peace Council • Col. Hkun Okker, Patron, Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization • Central Committee member Sai Ba Tun, Shan State Progress Party • Secretary-General Ta Aik Nyunt, Wa National Organization NCCT member Organizations: 1. Arakan Liberation Party 2. Arakan National Council 3. Arakan Army 4. Chin National Front 5. Democratic Karen Benevolent Army 6. Karenni National Progressive Party 7. Chairman, Karen National Union 8. KNU/KNLA Peace Council 9. Lahu Democratic Union 10. Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army 11. New Mon State Party 12. Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization 13. Palaung State Liberation Front 14. Shan State Progress Party 15. Wa National Organiztion 16. Kachin Independence Organization Note: Representatives of Restoration Council of Shan State attended the ethnic armed organizations conference held in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO. -

English 2014

The Border Consortium November 2014 PROTECTION AND SECURITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH EAST BURMA / MYANMAR With Field Assessments by: Committee for Internally Displaced Karen People (CIDKP) Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) Karen Environment and Social Action Network (KESAN) Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG) Karen Offi ce of Relief and Development (KORD) Karen Women Organisation (KWO) Karenni Evergreen (KEG) Karenni Social Welfare and Development Centre (KSWDC) Karenni National Women’s Organization (KNWO) Mon Relief and Development Committee (MRDC) Shan State Development Foundation (SSDF) The Border Consortium (TBC) 12/5 Convent Road, Bangrak, Suite 307, 99-B Myay Nu Street, Sanchaung, Bangkok, Thailand. Yangon, Myanmar. E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.theborderconsortium.org Front cover photos: Farmers charged with tresspassing on their own lands at court, Hpruso, September 2014, KSWDC Training to survey customary lands, Dawei, July 2013, KESAN Tatmadaw soldier and bulldozer for road construction, Dawei, October 2013, CIDKP Printed by Wanida Press CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Context .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ -

Displacement and Poverty in South East Burma/Myanmar

It remains to be seen how quickly and effectively the new DISPLACEMENT government will be able to tackle poverty, but there has not yet been any relaxation of restrictions on humanitarian AND POVERTY access into conflict-affected areas. In this context, the vast majority of foreign aid continues to be channelled into areas IN SOUTH EAST not affected by armed conflict such as the Irrawaddy/ Ayeyarwady Delta, the Dry Zone and Rakhine State. While responding to demonstrated needs, such engagement is BURMA/MYANMAR building trust with authorities and supporting advocacy for increased humanitarian space throughout the country. Until this confidence building process translates into access, 2011 cross-border aid will continue to be vital to ensure that the needs of civilians who are affected by conflict in the South East and cannot be reached from Yangon are not further marginalised. overty alleviation has been recognised by the new A new government in Burma/Myanmar offers the possibility The opportunity for conflict transformation will similarly government as a strategic priority for human of national reconciliation and reform after decades of conflict. require greater coherence between humanitarian, political, Thailand Burma Border Consortium (TBBC) development. While official figures estimate that a Every opportunity to resolve grievances, alleviate chronic development and human rights actors. Diplomatic www.tbbc.org quarter of the nation live in poverty, this survey poverty and restore justice must be seized, as there remain engagement with the Government in Naypidaw and the non Download the full report from Psuggests that almost two thirds of households in rural areas many obstacles to breaking the cycle of violence and abuse. -

China Thailand Laos

MYANMAR IDP Sites in Shan State As of 30 June 2021 BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH MYANMAR Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND CHINA List of IDP Sites In nothern Shan No. State Township IDP Site IDPs 1 Hseni Nam Sa Larp 267 2 Hsipaw Man Kaung/Naung Ti Kyar Village 120 3 Bang Yang Hka (Mung Ji Pa) 162 4 Galeng (Palaung) & Kone Khem 525 5 Galeng Zup Awng ward 5 RC 134 6 Hu Hku & Ho Hko 131 SAGAING Man Yin 7 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church) 245 Man Pying Loi Jon 8 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church-2) 155 Man Nar Pu Wan Chin Mu Lin Huong Aik 9 Mai Yu Lay New (Ta'ang) 398 Yi Hku La Shat Lum In 22 Nam Har 10 Kutkai Man Loi 84 Ngar Oe Shwe Kyaung Kone 11 Mine Yu Lay village ( Old) 264 Muse Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan 12 Mung Hawm 170 Nawng Mo Nam Kat Ho Pawt Man Hin 13 Nam Hpak Ka Mare 250 35 ☇ Konkyan 14 Nam Hpak Ka Ta'ang ( Aung Tha Pyay) 164 Chaung Wa 33 Wein Hpai Man Jat Shwe Ku Keng Kun Taw Pang Gum Nam Ngu Muse Man Mei ☇ Man Ton 15 New Pang Ku 688 Long Gam 36 Man Sum 16 Northern Pan Law 224 Thar Pyauk ☇ 34 Namhkan Lu Swe ☇ 26 Kyu Pat 12 KonkyanTar Shan Loi Mun 17 Shan Zup Aung Camp 1,084 25 Man Set Au Myar Ton Bar 18 His Aw (Chyu Fan) 830 Yae Le Man Pwe Len Lai Shauk Lu Chan Laukkaing 27 Hsi Hsar 19 Shwe Sin (Ward 3) 170 24 Tee Ma Hsin Keng Pang Mawng Hsa Ka 20 Mandung - Jinghpaw 147 Pwe Za Meik Nar Hpai Nyo Chan Yin Kyint Htin (Yan Kyin Htin) Manton Man Pu 19 Khaw Taw 21 Mandung - RC 157 Aw Kar Shwe Htu 13 Nar Lel 18 22 Muse Hpai Kawng 803 Ho Maw 14 Pang Sa Lorp Man Tet Baing Bin Nam Hum Namhkan Ho Et Man KyuLaukkaing 23 Mong Wee Shan 307 Tun Yone Kyar Ti Len Man Sat Man Nar Tun Kaw 6 Man Aw Mone Hka 10 KutkaiNam Hu 24 Nam Hkam - Nay Win Ni (Palawng) 402 Mabein Ton Kwar 23 War Sa Keng Hon Gyet Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Nawng Ae 25 Namhkan Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) 338 Si Ping Kaw Yi Man LongLaukkaing Man Kaw Ho Pang Hopong 9 16 Nar Ngu Pang Paw Long Htan (Tart Lon Htan) 26 Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) II 32 Ma Waw 11 Hko Tar Say Kaw Wein Mun 27 Nam Hkam Catholic Church ( St. -

New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State?

CRS INSIGHT New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State? February 15, 2019 (IN11046) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) Approximately 250 Chin and Rakhine refugees entered into Bangladesh's Bandarban district in the first week of February, trying to escape the fighting between Burma's military, or Tatmadaw, and one of Burma's newest ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the Arakan Army (AA). Bangladesh's Foreign Minister Abdul Momen summoned Burma's ambassador Lwin Oo to protest the arrival of the Rakhine refugees and the military clampdown in Rakhine State. Bangladesh has reportedly closed its border to Rakhine State. U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee released a press statement on January 18, 2019, indicating that heavy fighting between the AA and the Tatmadaw had displaced at least 5,000 people. She also called on the Rakhine State government to reinstate the access for international humanitarian organizations. The Conflict Between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw The AA was formed in Kachin State in 2009, with the support of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). In 2015, the AA moved some of its soldiers from Kachin State to southwestern Chin State, and began attacking Tatmadaw security bases in Chin State and northern Rakhine State (see Figure 1). In late 2017, the AA shifted more of its operations into northeastern Rakhine State. According to some estimates, the AA has approximately 3,000 soldiers based in Chin and Rakhine States. Figure 1. Reported Clashes between Arakan Army and Tatmadaw Source: CRS, utilizing data provided by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

Myanmar Information Management Unit

Myanmar Information Management Unit (! (! (! Myanmar - South East Reg(! ion (! (! ! ( (! Ayadaw (! (! !( 30' 95°0'E 30' 96°0'E 30' 97°0'E 30' 98°0'E 30' 99°0'E 30' 100°0'E 30' Madaya (! Pangsang ! SHAN NORTH (! ( Monywa Yinmabin (! STATE (! Mandalay Pyinoolwin N N ' City Mongpauk ' 0 !( 0 ° Salingyi (! BHUTAN ° 2 Chaung-U Matman 2 2 ! .! 2 Pale ( (! Myinmu Kyethi (! (! (! (! Monghsu INDIA (! Ngazun Sagaing (! Kachin Myaung .! Myitnge Mongyang State Tada-U !( (! (! (! Monghsu Mongkhet CHINA Sintgaing (! (! Mongkaing Kyethi Mongsan SagaingMongla (! (Hmonesan) Yesagyo Mongnawng !( Regio(!n Myaing Kyaukse Intaw Mongkaung !( (! (! (! !( (! Lawksawk Pauk Myingyan (! (! Natogyi Myittha Chin Shan State State !( (! (! Mandalay Mongping Region Pakokku Tontar Mongyu Kunhing Kar Li (! !( !( (! Laihka !( KengtuRngakhine Taungtha MANDALAY Magway K(!unhing (! State (! Ywangan Lawksawk (! Laihka Region REGION (! LAOS Nyaung-U Mongyawng Ywangan (! (! Ngathayouk Kayah (! (! Bagan !( (! State !( Mahlaing Wundwin Kho Lam (! (! !( Bago Region Pindaya N N ' ' 0 Pinlon 0 ° ° 1 !( 1 2 Pindaya 2 Hopong Loilen Loilen Kayin THAILAND Seikphyu Chauk (! Ayeyarwady Yangon Meiktila (! Nansang SHAN SOUTH ReMgoionnghpyRaekgion State (!(! Kenglat Kyaukpadaung (! Thazi (! (! !( (! (! Nansang STATE Taunggyi Shwenyaung !( (! Kengtawng !( ! Hopong !( Mongkhoke Mon .Ayetharyar !( Tarlay !( State Nyaungshwe Mongnai Kalaw!( Kalaw (! Pyawbwe (! Aungpan SHAN EAST Salin (! Tanintharyi (! STATE Region Mongnai Monghsat (! (! Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Nyaungshwe Tachileik (! Yamethin Hsihseng -

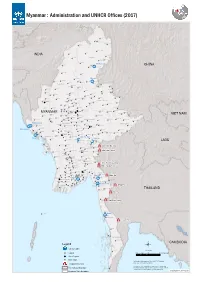

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017)

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017) Nawngmun Puta-O Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Sumprabum Lahe Tanai INDIA Tsawlaw Hkamti Kachin Chipwi Injangyang Hpakan Myitkyina Lay Shi Myitkyina CHINA Mogaung Waingmaw Homalin Mohnyin Banmauk Bhamo Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Momauk Pinlebu Katha Sagaing Mansi Muse Wuntho Konkyan Kawlin Tigyaing Namhkan Tonzang Mawlaik Laukkaing Mabein Kutkai Hopang Tedim Kyunhla Hseni Manton Kunlong Kale Kalewa Kanbalu Mongmit Namtu Taze Mogoke Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Falam Mingin Thabeikkyin Ye-U Khin-U Shan (North) ThantlangHakha Tabayin Hsipaw Namphan ShweboSingu Kyaukme Tangyan Kani Budalin Mongyai Wetlet Nawnghkio Ayadaw Gangaw Madaya Pangsang Chin Yinmabin Monywa Pyinoolwin Salingyi Matman Pale MyinmuNgazunSagaing Kyethi Monghsu Chaung-U Mongyang MYANMAR Myaung Tada-U Mongkhet Tilin Yesagyo Matupi Myaing Sintgaing Kyaukse Mongkaung VIET NAM Mongla Pauk MyingyanNatogyi Myittha Mindat Pakokku Mongping Paletwa Taungtha Shan (South) Laihka Kunhing Kengtung Kanpetlet Nyaung-U Saw Ywangan Lawksawk Mongyawng MahlaingWundwin Buthidaung Mandalay Seikphyu Pindaya Loilen Shan (East) Buthidaung Kyauktaw Chauk Kyaukpadaung MeiktilaThazi Taunggyi Hopong Nansang Monghpyak Maungdaw Kalaw Nyaungshwe Mrauk-U Salin Pyawbwe Maungdaw Mongnai Monghsat Sidoktaya Yamethin Tachileik Minbya Pwintbyu Magway Langkho Mongpan Mongton Natmauk Mawkmai Sittwe Magway Myothit Tatkon Pinlaung Hsihseng Ngape Minbu Taungdwingyi Rakhine Minhla Nay Pyi Taw Sittwe Ann Loikaw Sinbaungwe Pyinma!^na Nay Pyi Taw City Loikaw LAOS Lewe