Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin minorityrights.org/minorities/kachin/ June 19, 2015 Profile The Kachin encompass a number of ethnic groups speaking almost a dozen distinct languages belonging to the Tibeto-Burman linguistic family who inhabit the same region in the northern part of Burma on the border with China, mainly in Kachin State. Strictly speaking, these languages are not necessarily closely related, and the term Kachin at times is used to refer specifically to the largest of the groups (the Kachin or Jingpho/Jinghpaw) or to the whole grouping of Tibeto-Burman speaking minorities in the region, which include the Maru, Lisu, Lashu, etc. The exact Kachin population is unknown due to the absence of reliable census data in Burma for more than 60 years. Most estimates suggest there may in the vicinity of 1 million Kachin in the country. The Kachin, as well as the Chin, are one of Burma’s largest Christian minorities: though once again difficult to assess, it is generally thought that between two-thirds and 90 per cent of Kachin are Christians, with others following animist practices or Buddhists. Historical context It is generally thought that the Kachin gradually moved south from their ancestral land on the Tibetan plateau through Yunnan in southern China to arrive in the northern region of what would become Burma sometime during the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, making the Kachin relative newcomers. Their position in this borderland part of South-East Asia meant that the Kachin were often outside of the sphere of influence of Burman kings. Their strength was such by the Third Anglo-Burmese War of 1885 that, while the British were taking Mandalay, the Kachin were getting ready to take advantage of the Burman kingdom’s weakness to attack and take over Mandalay themselves. -

New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State?

CRS INSIGHT New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State? February 15, 2019 (IN11046) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) Approximately 250 Chin and Rakhine refugees entered into Bangladesh's Bandarban district in the first week of February, trying to escape the fighting between Burma's military, or Tatmadaw, and one of Burma's newest ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the Arakan Army (AA). Bangladesh's Foreign Minister Abdul Momen summoned Burma's ambassador Lwin Oo to protest the arrival of the Rakhine refugees and the military clampdown in Rakhine State. Bangladesh has reportedly closed its border to Rakhine State. U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee released a press statement on January 18, 2019, indicating that heavy fighting between the AA and the Tatmadaw had displaced at least 5,000 people. She also called on the Rakhine State government to reinstate the access for international humanitarian organizations. The Conflict Between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw The AA was formed in Kachin State in 2009, with the support of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). In 2015, the AA moved some of its soldiers from Kachin State to southwestern Chin State, and began attacking Tatmadaw security bases in Chin State and northern Rakhine State (see Figure 1). In late 2017, the AA shifted more of its operations into northeastern Rakhine State. According to some estimates, the AA has approximately 3,000 soldiers based in Chin and Rakhine States. Figure 1. Reported Clashes between Arakan Army and Tatmadaw Source: CRS, utilizing data provided by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). -

7 Publicversion Myanmar Janv2018

The Strategy and Tactics of Myanmar COIN Strategy since 2010 note OBSERVATOIRE ASIE DU SUD-EST 2017/2018 OBSERVATOIRE Note d’actualité n°7/8 de l’Observatoire de l’Asie du Sud-Est, cycle 2017-2018 Janvier 2018 Along with the recent democratization, the ongoing peace process has transformed the Counter Insurgency (COIN) strategy and tactics of the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw). Political reforms after 2010 created the new dynamic of civil-military relation, shifting paradigm in the COIN activities. Taking off from the old strategy of four-cut policy, COIN tactics vary, depend ing on the regions. From the conventional tactics with peace process as leverage in Kachin state, use of militia with the four-cut policy is also active in Shan States. Although militias still remain the backbone of the COIN operations, as the result of the Standard Army reform process, their role has soon to change. Maison de la Recherche de l’Inalco 2 rue de Lille 75007 Paris - France Tél. : +33 1 75 43 63 20 Fax. : +33 1 75 43 63 23 ww.centreasia.eu [email protected] siret 484236641.00037 List of the acronyms & abbreviations Introduction 1. Militias – Backbone of the COIN Introduction 2. COIN Operations in the Kachin State Insurgency and independence are two sides of the same Background of the conflict coin. Since 2010, the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) Tatmadaw’s Tactics in Kachin State has adopted numbers of Counter Insurgency (COIN) Tatmadaw’s types of operations in Kachin strategies and tactics to expand the government State control area and reduce the contested areas controlled Resources by non-state actors: the ethnic and communist insurgents. -

Finding an Endgame in Kachin State the KIO’S Strategies for Finding a Resolution to the Conflict

EBO Background Paper - No .3 | 2018 September 2018 AUTHOR | Paul Keenan Finding an Endgame in Kachin State The KIO’s strategies for finding a resolution to the conflict Since 9 June 2011, Kachin State has seen open (CEFU). The Committee’s purpose was to conflict between the Kachin Independence Army consolidate a political front at a time when the and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military). The Kachin ceasefire groups faced perceived imminent attacks Independence Organisation had signed a ceasefire by the Tatmadaw. However, in November 2010 agreement with the regime in 1994 and since then shortly after the Myanmar elections, the political had lived in relative peace until the ceasefire was grouping was transformed into a military united broken by the Tatmadaw in June 2011. front. At a conference held from the 12-16 February 2011, CEFU declared its dissolution and the The increased territorial infractions by the formation of the United Nationalities Federal Tatmadaw combined with economic exploitation Council (UNFC). The UNFC, which was at that time by China in Kachin territory, especially the comprised of 12 ethnic organisations1, stated that: construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam, left the Kachin Independence Organisation with very The goal of the UNFC is to establish the little alternative but to return to armed resistance future Federal Union (of Myanmar) and to prevent further abuses of its people and their the Federal Union Army is formed for territory’s natural resources. Despite this, however, giving protection to the people of the the political situation since the beginning of country.2 hostilities has changed significantly. -

Kachin State WATCH

H U M A N R I G H T S “UNTOLD MISERIES” Wartime Abuses and Forced Displacement in Kachin State WATCH “Untold Miseries” Wartime Abuses and Forced Displacement in Burma’s Kachin State Copyright © 2012 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-874-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2012 1-56432-874-0 “Untold Miseries” Wartime Abuses and Forced Displacement in Burma’s Kachin State Map of Burma ...................................................................................................................... i Detailed Map of Kachin State ............................................................................................. -

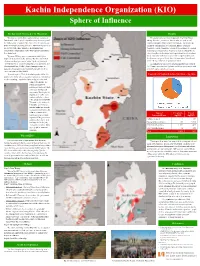

Control of Cropland in Kachin State - Sq

Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) Sphere of Influence Background: Insurgency in Myanmar Results Myanmar is a multiethnic country and was a colony of The global land-cover data map provided by ESA Climate Britain until 1948. It practiced parliamentary democracy until Change Initiative (2010) is used to calculate the total area of the military took a coup in 1962. Since then, the country was cropland (in square kilometers) in Kachin State. For simplicity, under military dictatorship until 2011. Myanmar has also been (irrigated croplands, rain-fed croplands, mosaic croplands/ in civil war with ethnic minorities including Kachin vegetation, mosaic vegetation/ croplands) are grouped as cropland. Independence Organization (KIO) who fight for autonomy in (closed to open broadleaved evergreen or semi-deciduous forest, their home land. closed broadleaved deciduous forest, open broadleaved deciduous Myanmar Military wrote a constitution which gives forest, closed needleleaved evergreen forest, open needleleaved unprecedented powers to the military. The November 2010 deciduous or evergreen forest, closed to open mixed broadleaved election was largely seen as a “sham” by the international and needleleaved forest) are grouped as forest. community. The de facto military party, Union Solidarity and According to the land-cover data, Kachin State has a total of Development Party (USDP) claimed outright victory. A 4,671 square kilometers of cropland, and 36 percent of which falls nominal civilian government led by ex-general Thein Sein in the KIO sphere of influence zones. came into power in March 2011. To much surprise, Thein Sein administration initiated a Control of Cropland in Kachin State - Sq. Km. number of reforms: release of political prisoners, relaxation of media censorship, economic reforms and peace talks with ethnic rebel groups. -

Myanmar Issue Brief No

CHINA, THE UNITED STATES AND THE KACHIN CONFLICT GREAT POWERS AND THE CHANGING MYANMAR ISSUE BRIEF NO. 2 JANUARY 2014 [UPDATED] China, the United States and the Kachin Conflict By Yun Sun This issue brief examines the development of the Kachin conflict in northern Myanmar’s Kachin and Shan states, the negotiations between the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) and the Myan- mar government, and the roles China and the United States have played in the conflict. KEY FINDINGS: 1 The prolonged Kachin conflict is a 3 The disagreements on terms have 5 Promoting national peace and major obstacle to Myanmar’s national hindered a formal cease-fire. In ad- reconciliation is a pillar of the US reconciliation and a challenging test dition, the existing economic inter- policy toward Myanmar. However, the for the democratization process. est groups profiting from the armed United States is being very careful not conflict have further undermined the to impose itself into the peace process prospect for progress. itself, including Kachin talks, given 2 The KIO and the Myanmar the government’s sensitivity that the government differ on the priority process remains an internal affair of between the cease-fire and the political 4 China intervened in the Kachin ne- the country. dialogue. Without addressing this gotiations in 2013 to protect its national difference, the nationwide peace interests. A crucial motivation was a accord proposed by the government concern about the “internationaliza- will most likely lack the KIO’s tion” of the Kachin issue and the poten- participation. tial US role along the Chinese border. -

Jadeand Conflict

JADE AND CONFLICT Myanmar’s Vicious Circle June 2021 2 CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS / MAIN ARMED ORGANISATIONS ACTIVE IN THE JADE SECTOR .................. 4 MAP OF MYANMAR ............................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 1. JADE AND CONFLICT: MYANMAR’S VICIOUS CIRCLE ...................................................................... 10 1.1 The NLD attempts to break the jade-conflict nexus ..................................................................................... 10 1.2 Mining reform derailed .................................................................................................................................. 11 Case Study: The 2019 Gemstone Law ........................................................................................................... 12 Case Study: State watchdog MGE keeps cosy industry ties rife with conflicts of interest .......................... 18 1.3 Jade after the coup ........................................................................................................................................ 22 2. ARMED GROUPS HOOKED ON JADE REVENUES .............................................................................. 26 2.1 The Tatmadaw profits from control over mining ........................................................................................ -

Politics of Ethnic Armed Organisations After the Myanmar Coup

New friends, old enemies: Politics of Ethnic Armed Organisations after the Myanmar Coup Policy Briefing – SEARBO Prepared by Samuel Hmung,, Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, College of Asia and the Pacific , ANU. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Dr. Nick Cheesman and Nick Ross for comments on earlier versions of this article and report. This report was made possible by funding from Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade for the ‘Supporting the Rules- Based Order’ project of PSC. The Author Salai Samuel Hmung is a research officer of the SEARBO project. He received his Master of Political Science (Advanced) from the Australian National University’s Coral Bell School of Asia and Pacific Affairs. His master thesis applied an original power- sharing framework to explore and compare the preferences of Myanmar’s elite political actors for power-sharing through their public statements from 2015-2020 by using a dictionary-based content analysis method. His broader research interests include ethnic politics, civil conflict, and power-sharing institutions. DISCLAIMER This article is part of a New Mandala series related to the Supporting the Rules-Based Order in Southeast Asia (SEARBO) project. This project is run by the Department of Political and Social Change at the Australian National University and funded by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The opinions expressed here are the authors’ own and are not meant to represent those of the ANU or DFAT. Published by Co-sponsored by Front cover -

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER July 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions Around Political Violence in Myanmar

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around Political Violence in Myanmar Coding political violence in Myanmar poses several methodological challenges given the complexity of the many conflicts in the country. In addition to armed conflict between the military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in the borderlands, the military in recent years has used nationlist sentiments to wage a campaign of violence and discrimination against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine state. Further, in the country’s heartland, demonstrations have persisted not just over land and labor issues, but also to demand changes to the military-drafted 2008 constitution. A reference map of the country can be found at the end of this document. Shortly after Myanmar gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1948, several ethnic groups took up arms against the state, demanding equality and the right to self-determination. Divisions between ethnic groups had long been fostered by the colonial practice of ‘divide-and-rule’. This resulted in the center of the country being governed separately from the frontier areas where many ethnic minorities reside. Despite the signing of the Panglong Agreement prior to 1 independence, the failure of the central government to address ethnic concerns led to rebellions by Karen rebels in 1949 and by Kachin rebels in the early 1960s. Other ethnic minorities also took up arms during this period. In March 1962, the military seized power in a coup. It continued with a ‘divide-and-rule’ approach in its dealings with ethnic armed groups, and further adopted a policy of ‘four cuts’, which aimed to eliminate local support for armed groups (Smith, 1991). -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 486 | NOVEMBER 2020 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org The Arakan Army in Myanmar: Deadly Conflict Rises in Rakhine State By David Scott Mathieson Contents Introduction: A Deadly Conflict Rises in Rakhine State .................3 Background and Rise of the Arakan Army ......................4 The Nature of Arakan Army Warfare and Strategy ...................7 Attitudes toward Rohingya and Muslim Minorities ................ 15 Conclusions and Recommendations ...................... 17 Kyaw Han, general secretary of United League of Arakan/Arakan Army, attends a March 2019 meeting with government, military, and ethnic armed organizations. (Photo by Aung Shine Oo/AP) Summary • Myanmar’s most serious conflict Tatmadaw and compounding the narrowing possibilities for political in many decades has emerged human and physical damage. solutions. This conflict will continue in Rakhine State between the • The AA’s sophisticated communi- to escalate absent the AA’s inclu- Myanmar armed forces (Tatmad- cations strategies use social me- sion in the peace process, send- aw) and the Arakan Army (AA), de- dia to swell its recruitment base, ing Rakhine State into a downward manding self-determination for the build civilian support, trade insults spiral that could seriously damage Buddhist Rakhine ethnic minority. It with the Tatmadaw, and reach an the rest of the country. leaves Rohingya refugees with lit- international audience. • With strategic investments to pro- tle chance of a safe return. • Government efforts to marginalize tect in Rakhine’s Kyaukphyu port, • The AA’s guerrilla tactics have and demonize the AA are counter- influence on other armed groups, caused many military and civil- productive with the Rakhine pop- and an interest in the peace pro- ian casualties, evoking a typically ulation, hardening attitudes and cess, China is the only external fierce armed response from the player that can influence the AA.