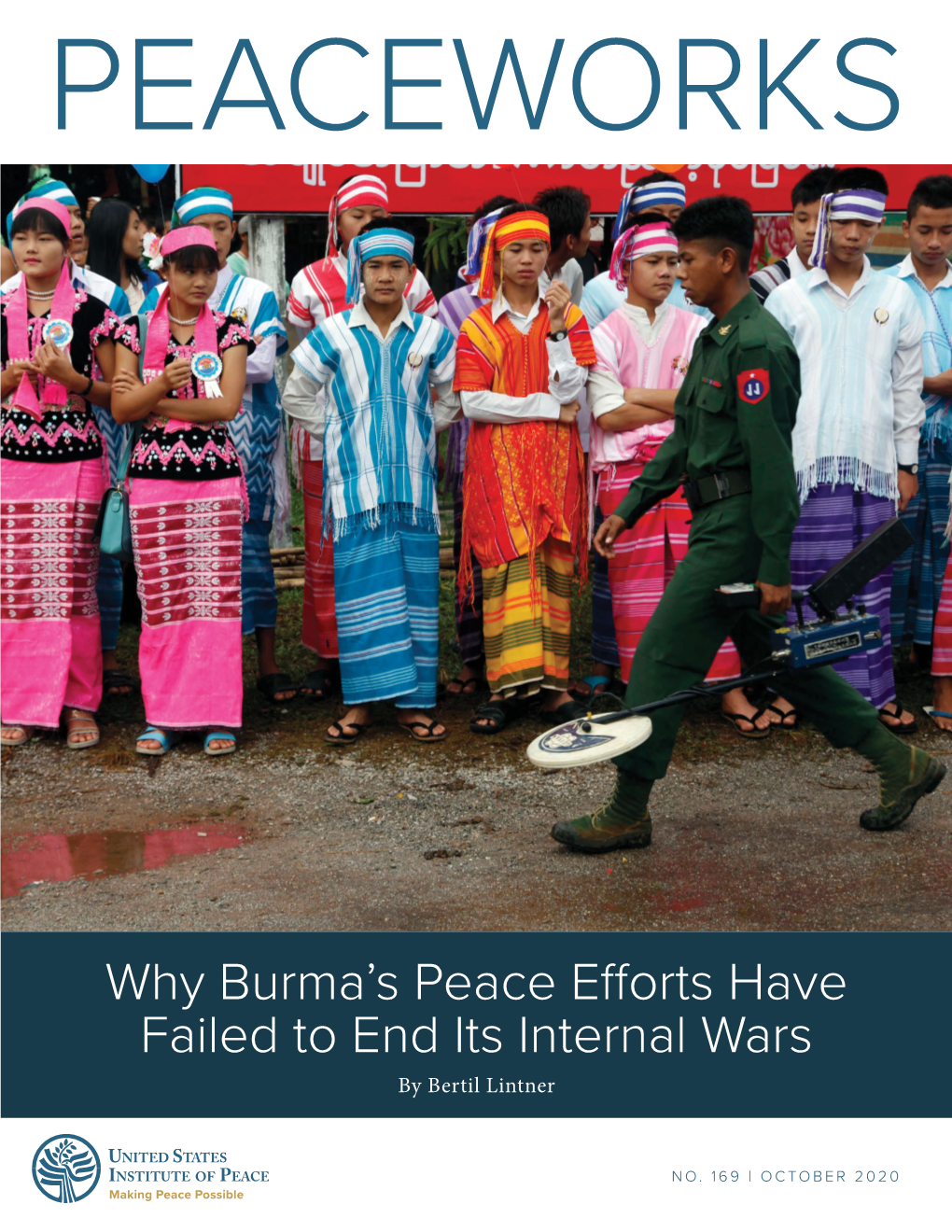

Why Burma's Peace Efforts Have Failed to End Its Internal Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Outline of the History of the Communist Party of Burma

A SHORT OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF .· THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF BURMA I Burma was an independent kingdom before annexation by the British imperialist in 1824. In 1885 British imperialist annexed whole of Burma. Since that time, Burmese people have never given up their fight for regaining their independence. Various armed uprisings and other legal forms of strug gle were used by the Burmese people in their fight to regain indep~ndence. In 19~8 the biggest and the broadest anti-British general _strike over-ran the whole country. The workers were on strike, the peasants marched up to Rangoon and all the students deserted their class-room to join the workers and peasants. It was an unprecendented anti-British movement in Burma popularly called in Burmese as "1300th movement". Out of this national and class struggle of the Burmese people and working class emerges the Communist Party of Burma. II The Communist Party of Burma was of!i~ially founded on 15th ~_!l_g~s_b 1939 by _!!nitil)K all MarxisLgr.9J!l!§ in Burma, III From the day of inception, CPB launched an active anti-British struggles up till 1941. It was the core of CPB leadership that led ahti British struggles up till the second world war. IV In 1941, after the Hitlerites treacherously attacked the Soviet Union, CPB changed its tactics and directed its blows against the fascists. v In 1942, Burma was invaded by the Japanese fascists. From that time onwards up till 1945, CPB worked unt~ringly to oppose the Japanese fa~ists 1 . -

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma(<Special Issue

State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare Title and Politics in Colonial Burma(<Special Issue>State Formation in Comparative Perspectives) Author(s) Callahan, Mary P. Citation 東南アジア研究 (2002), 39(4): 513-536 Issue Date 2002-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/53713 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 39, No. 4, March 2002 State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma* Mary P. CALLAHAN** Normally, society is organized for life; the object of Leviathan was to organise it for production. J.S. Furnivall [1939: 124] Abstract This article examines the construction of the colonial security apparatus in Burma, within the broader British colonial project in eastern Asia. During the colonial period, the state in Burma was built by default, as no one in London or India ever mapped out a strategy for establishing governance in this outpost. Instead of sending in legal, commercial or police experts to establish law and order—the preconditions of the all-important commerce— Britain sent the Indian Army, which faced an intensity and landscape of guerilla resistance never anticipated. Early forays into the establishment of law and order increasingly became based on conceptions of the population as enemies to be pacified, rather than subjects to be incorporated into or even ignored by the newly defined political entity. The character of armed administration in colonial Burma had a disproportionate impact on how that popula- tion came to be regarded, treated, legalized and made into subjects of the Raj. -

Burma – Myanmar

BURMA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Jerome Holloway 1947-1949 Vice Consul, Rangoon Edwin Webb Martin 1950-1051 Consular Officer, Rangoon Joseph A. Mendenhall 1955-1957 Economic Officer, Office of Southeast Asian Affairs, Washington DC William C. Hamilton 1957-1959 Political Officer, Rangoon Arthur W. Hummel, Jr. 1957-1961 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Kenneth A. Guenther 1958-1959 Rangoon University, Rangoon Cliff Forster 1958-1960 Information Officer, USIS, Rangoon Morton Smith 1958-1963 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Morton I. Abramowitz 1959 Temporary Duty, Economic Officer, Rangoon Jack Shellenberger 1959-1962 Branch Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Moulmein John R. O’Brien 1960-1962 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Robert Mark Ward 1961 Assistant Desk Officer, USAID, Washington, DC George M. Barbis 1961-1963 Analyst for Thailand and Burma, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington DC Robert S. Steven 1962-1964 Economic Officer, Rangoon Ralph J. Katrosh 1962-1965 Political Officer, Rangoon Ruth McLendon 1962-1966 Political/Consular Officer, Rangoon Henry Byroade 1963-1969 Ambassador, Burma 1 John A. Lacey 1965-1966 Burma-Cambodia Desk Officer, Washington DC Cliff Southard 1966-1969 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Edward C. Ingraham 1967-1970 Political Counselor, Rangoon Arthur W. Hummel Jr. 1968-1971 Ambassador, Burma Robert J. Martens 1969-1970 Political – Economic Officer, Rangoon G. Eugene Martin 1969-1971 Consular Officer, Rangoon 1971-1973 Burma Desk Officer, Washington DC Edwin Webb Martin 1971-1973 Ambassador, Burma John A. Lacey 1972-1975 Deputy Chief of Mission, Rangoon James A. Klemstine 1973-1976 Thailand-Burma Desk Officer, Washington DC Frank P. Coward 1973-1978 Cultural Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Richard M. -

Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer

www.ssoar.info Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. https:// doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-2018.1-2 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.de Aktuelle Südostasienforschung Current Research on Southeast Asia Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: The Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Rainer Einzenberger ► Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier capitalism and politics of dispossession in Myanmar: The case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) nickel mine in Chin State. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. Since 2010, Myanmar has experienced unprecedented political and economic changes described in the literature as democratic transition or metamorphosis. The aim of this paper is to analyze the strategy of accumulation by dispossession in the frontier areas as a precondition and persistent element of Myanmar’s transition. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma*

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 39, No. 4, March 2002 State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma* Mary P. CALLAHAN** Normally, society is organized for life; the object of Leviathan was to organise it for production. J.S. Furnivall [1939: 124] Abstract This article examines the construction of the colonial security apparatus in Burma, within the broader British colonial project in eastern Asia. During the colonial period, the state in Burma was built by default, as no one in London or India ever mapped out a strategy for establishing governance in this outpost. Instead of sending in legal, commercial or police experts to establish law and order—the preconditions of the all-important commerce— Britain sent the Indian Army, which faced an intensity and landscape of guerilla resistance never anticipated. Early forays into the establishment of law and order increasingly became based on conceptions of the population as enemies to be pacified, rather than subjects to be incorporated into or even ignored by the newly defined political entity. The character of armed administration in colonial Burma had a disproportionate impact on how that popula- tion came to be regarded, treated, legalized and made into subjects of the Raj. Administra- tive simplifications along territorial and racial lines resulted in political, economic, and social boundaries that continue to divide the country today. Bureaucratic and security mech- anisms politicized violence along territorial and racial lines, creating “two Burmas” in the administrative and security arms of the state. Despite the “laissez-faire” proclamations of colonial state officials in Burma, this geographically and functionally limited state nonethe- less established durable administrative structures that precluded any significant integration throughout the territory for a century to come. -

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team Seventeen Ethnic Armed Organizations held a conference in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO/KIA on 30 Oct – 2 Nov 2013. At the end of the conference, ethnic leaders established Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT) on Nov 2, 2013. The NCCT will represent to member ethnic armed organizations when negotiating with government peace negotiation team, UPWC. NCCT Leader: • Vice-Chairman : Nai Hong Sar, New Mon State Party • Deputy Leader 1 : General Secretary – Padoh Kwe Htoo Win (Karen National Union) • Deputy Leader 2 : Deputy Commander-in-Chief – Maj. Gen. Gun Maw (KIA) Member • Lt. Col. Kyaw Han, Arakan Army • Central Committee Member Ms. Mra Raza Lin, Arakan Liberation Party • General Secretary Twan Zaw, Arakan National Council • Presidium Dr. Lian Sakhong, Chin National Front • Col. Saw Lont Lon, Democratic Karen Benevolent Army • Secretary-2 Shwe Myo Thant, Karenni National Progressive Party • Gen. Dr. Timothy, Foreign Affairs, KNU/KNLA Peace Council • Col. Hkun Okker, Patron, Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization • Central Committee member Sai Ba Tun, Shan State Progress Party • Secretary-General Ta Aik Nyunt, Wa National Organization NCCT member Organizations: 1. Arakan Liberation Party 2. Arakan National Council 3. Arakan Army 4. Chin National Front 5. Democratic Karen Benevolent Army 6. Karenni National Progressive Party 7. Chairman, Karen National Union 8. KNU/KNLA Peace Council 9. Lahu Democratic Union 10. Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army 11. New Mon State Party 12. Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization 13. Palaung State Liberation Front 14. Shan State Progress Party 15. Wa National Organiztion 16. Kachin Independence Organization Note: Representatives of Restoration Council of Shan State attended the ethnic armed organizations conference held in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO. -

Smart Border Management an Indian Perspective September 2016

Content Smart border management p4 / Responding to border management challenges p7 / Challenges p18 / Way forward: Smart border management p22 / Case studies p30 Smart border management An Indian perspective September 2016 www.pwc.in Foreword India’s geostrategic location, its relatively sound economic position vis-à-vis its neighbours and its liberal democratic credentials have induced the government to undertake proper management of Indian borders, which is vital to national security. In Central and South Asia, smart border management has a critical role to play. When combined with liberal trade regimes and business-friendly environments, HIğFLHQWFXVWRPVDQGERUGHUFRQWUROVFDQVLJQLğFDQWO\LPSURYHSURVSHFWVIRUWUDGH and economic growth. India shares 15,106.7 km of its boundary with seven nations—Pakistan, China, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. These land borders run through different terrains; managing a diverse land border is a complex task but YHU\VLJQLğFDQWIURPWKHYLHZRIQDWLRQDOVHFXULW\,QDGGLWLRQ,QGLDKDVDFRDVWDO boundary of 7,516.6 km, which includes 5,422.6 km of coastline in the mainland and 2,094 km of coastline bordering islands. The coastline touches 9 states and 2 union territories. The traditional approach to border management, i.e. focussing only on border security, has become inadequate. India needs to not only ensure seamlessness in the legitimate movement of people and goods across its borders but also undertake UHIRUPVWRFXUELOOHJDOĠRZ,QFUHDVHGELODWHUDODQGPXOWLODWHUDOFRRSHUDWLRQFRXSOHG with the adoption of -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Intersection of Economic Development, Land, and Human Rights Law in Political Transitions: The Case of Burma THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Lauren Gruber Thesis Committee: Professor Scott Bollens, Chair Associate Professor Victoria Basolo Professor David Smith 2014 © Lauren Gruber 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF TABLES v ACNKOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTRACT OF THESIS vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Historical Background 1 Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century Political Transition 3 Scope 12 CHAPTER 2: Research Question 13 CHAPTER 3: Methods 13 Primary Sources 14 March 2013 International Justice Clinic Trip to Burma 14 Civil Society 17 Lawyers 17 Academics and Politicians 18 Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations 19 Transitional Justice 21 Basic Needs 22 Themes 23 Other Primary Sources 23 Secondary Sources 24 Limitations 24 CHAPTER 4: Literature Review Political Transitions 27 Land and Property Law and Policy 31 Burmese Legal Framework 35 The 2008 Constitution 35 Domestic Law 36 International Law 38 Private Property Rights 40 Foreign Investment: Sino-Burmese Relations 43 CHAPTER 5: Case Studies: The Letpadaung Copper Mine and the Myitsone Dam -- Balancing Economic Development with Human ii Rights and Property and Land Laws 47 November 29, 2012: The Letpadaung Copper Mine State Violence 47 The Myitsone Dam 53 CHAPTER 6: Legal Analysis of Land Rights in Burma 57 Land Rights Provided by the Constitution 57 -

Recent Arrests List

ƒ ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 8 of the Export and Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Lin of Special Branch President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s S: 25 of the Natural Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Naing law President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and parliament President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Union Assembly, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 5 (U) T Khun Myat M Joint House and Pyithu Hluttaw, the 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and lower house of the Myanmar President U Win Myint were detained. -

Arakan Army, AA)

Division de l’information, de la documentation et des recherches – DIDR 9 avril 2021 Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Armée de l’Arakan (Arakan Army, AA) Avertissement Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine, a été élaboré par la DIDR en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière et ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Arakan Army, (AA) Table des matières 1. Principales caractéristiques de l’Arakan Army ................................................................................ 3 1.1. Une organisation liée à la KIA et à l’UWSA ............................................................................. 3 1.2. Relations avec les autres organisations politico-militaires ...................................................... 3 2. Les opérations armées de l’AA ont entraîné des représailles massives ......................................... 4 3. Les interventions de l’AA à des fins logistiques dans les villages ................................................... 5 4. Enlèvements