Myanmar's Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer

www.ssoar.info Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. https:// doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-2018.1-2 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.de Aktuelle Südostasienforschung Current Research on Southeast Asia Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: The Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Rainer Einzenberger ► Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier capitalism and politics of dispossession in Myanmar: The case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) nickel mine in Chin State. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. Since 2010, Myanmar has experienced unprecedented political and economic changes described in the literature as democratic transition or metamorphosis. The aim of this paper is to analyze the strategy of accumulation by dispossession in the frontier areas as a precondition and persistent element of Myanmar’s transition. -

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team Seventeen Ethnic Armed Organizations held a conference in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO/KIA on 30 Oct – 2 Nov 2013. At the end of the conference, ethnic leaders established Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT) on Nov 2, 2013. The NCCT will represent to member ethnic armed organizations when negotiating with government peace negotiation team, UPWC. NCCT Leader: • Vice-Chairman : Nai Hong Sar, New Mon State Party • Deputy Leader 1 : General Secretary – Padoh Kwe Htoo Win (Karen National Union) • Deputy Leader 2 : Deputy Commander-in-Chief – Maj. Gen. Gun Maw (KIA) Member • Lt. Col. Kyaw Han, Arakan Army • Central Committee Member Ms. Mra Raza Lin, Arakan Liberation Party • General Secretary Twan Zaw, Arakan National Council • Presidium Dr. Lian Sakhong, Chin National Front • Col. Saw Lont Lon, Democratic Karen Benevolent Army • Secretary-2 Shwe Myo Thant, Karenni National Progressive Party • Gen. Dr. Timothy, Foreign Affairs, KNU/KNLA Peace Council • Col. Hkun Okker, Patron, Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization • Central Committee member Sai Ba Tun, Shan State Progress Party • Secretary-General Ta Aik Nyunt, Wa National Organization NCCT member Organizations: 1. Arakan Liberation Party 2. Arakan National Council 3. Arakan Army 4. Chin National Front 5. Democratic Karen Benevolent Army 6. Karenni National Progressive Party 7. Chairman, Karen National Union 8. KNU/KNLA Peace Council 9. Lahu Democratic Union 10. Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army 11. New Mon State Party 12. Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization 13. Palaung State Liberation Front 14. Shan State Progress Party 15. Wa National Organiztion 16. Kachin Independence Organization Note: Representatives of Restoration Council of Shan State attended the ethnic armed organizations conference held in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO. -

Yearbook Peace Processes.Pdf

School for a Culture of Peace 2010 Yearbook of Peace Processes Vicenç Fisas Icaria editorial 1 Publication: Icaria editorial / Escola de Cultura de Pau, UAB Printing: Romanyà Valls, SA Design: Lucas J. Wainer ISBN: Legal registry: This yearbook was written by Vicenç Fisas, Director of the UAB’s School for a Culture of Peace, in conjunction with several members of the School’s research team, including Patricia García, Josep María Royo, Núria Tomás, Jordi Urgell, Ana Villellas and María Villellas. Vicenç Fisas also holds the UNESCO Chair in Peace and Human Rights at the UAB. He holds a doctorate in Peace Studies from the University of Bradford, won the National Human Rights Award in 1988, and is the author of over thirty books on conflicts, disarmament and research into peace. Some of the works published are "Procesos de paz y negociación en conflictos armados” (“Peace Processes and Negotiation in Armed Conflicts”), “La paz es posible” (“Peace is Possible”) and “Cultura de paz y gestión de conflictos” (“Peace Culture and Conflict Management”). 2 CONTENTS Introduction: Definitions and typologies 5 Main Conclusions of the year 7 Peace processes in 2009 9 Main reasons for crises in the year’s negotiations 11 The peace temperature in 2009 12 Conflicts and peace processes in recent years 13 Common phases in negotiation processes 15 Special topic: Peace processes and the Human Development Index 16 Analyses by countries 21 Africa a) South and West Africa Mali (Tuaregs) 23 Niger (MNJ) 27 Nigeria (Niger Delta) 32 b) Horn of Africa Ethiopia-Eritrea 37 Ethiopia (Ogaden and Oromiya) 42 Somalia 46 Sudan (Darfur) 54 c) Great Lakes and Central Africa Burundi (FNL) 62 Chad 67 R. -

EBO Background Paper NO. 4 / 2015 AUGUST 2015 EBO MYANMAR

EBO Background Paper NO. 4 / 2015 AUGUST 2015 EBO MYANMAR AUTHOR | Paul Keenan ALL-INCLUSIVENESS IN AN ETHNIC CONTEXT After what had been recognised as successful ostensibly an agreement not to militarily engage talks in July that brought the Nationwide Ceasefire the government’s armed forces. Agreement (NCA) closer to fruition only three While two of the three main points, signatories and points remained to be addressed before a binding witnesses to the agreement, were satisfactorily agreement could be signed. Perhaps crucially the settled at a meeting between the Union Peace- most important for all concerned parties were making Work Committee (UPWC) and Ethnic Armed which groups are to be included in the signing of Organizations-Senior Delegation (SD), from 6 to 7 the NCA. This has become a particularly difficult August 2015, at the Myanmar Peace Centre, the point to address as the Government and the main one, all-inclusiveness, or more correctly who armed ethnic group leaders have differing views gets to sign the ceasefire agreement, continues as to the validity of those groups that can be a part to be unresolved and without compromise could of the process at the initial ceasefire stage. see the peace process delayed until well after There are six groups that are a major concern May 2016, as the 8 November election and the during these talks, each groups has a different installation of a new government is finalised. background, a different goal, and different claims Consequently, there remains little time left for an as to why they deserve to participate in what is agreement to be made. -

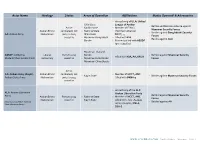

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma)

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Watchlist Mission Statement The Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict strives to end violations against children in armed conflicts and to guarantee their rights. As a global network, Watchlist builds partnerships among local, national and international nongovernmental organizations, enhancing mutual capacities and strengths. Working together, we strategically collect and disseminate information on violations against children in conflicts in order to influence key decision-makers to create and implement programs and policies that effectively protect children. Watchlist works within the framework of the provisions adopted in Security Council Resolutions 1261, 1314, 1379, 1460, 1539 and 1612, the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its protocols and other internationally adopted human rights and humanitarian standards. General supervision of Watchlist is provided by a Steering Committee of international nongovernmental organizations known for their work with children and human rights. The views presented in this report do not represent the views of any one organization in the network or the Steering Committee. For further information about Watchlist or specific reports, or to share information about children in a particular conflict situation, please contact: [email protected] www.watchlist.org Photo Credits Cover Photo: UNICEF/NYHQ2006- 1870/Robert Few Please Note: The people represented in the photos in this report are not necessarily themselves victims or survivors of human rights violations or other abuses. No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Notes on Methodology . Information contained in this report is current through January 1, 2009. -

Media Monitoring Report – UNHCR Thailand

Media Monitoring Report – UNHCR Thailand MEDIA MONITORING REPORT – OCTOBER 2015 NATIONWIDE CEASEFIRE AGREEMENT Eight ethnic armed organizations signed a Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) in Nay Pyi Taw on Thursday 15th October. It is a major step towards peace after more than six decades of civil conflict in the Southeast Asian country. The event was observed by foreign diplomats from 50 countries, political parties, civil society organizations as well as international witnesses including the United Nations, the European Union, China, India, Thailand and Japan.1 Three days before the formal signing of the NCA, the government removed the eight signatory groups from the list of "Unlawful Associations" and "Terrorist Organizations" respectively. The eight ethnic groups that signed the NCA with the government are: (1) Karen National Union (KNU) (2) Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA) (3) Karen National Liberation Army - Peace Council (KNLA-PC) (4) Chin National Front (CNF) (5) Pa-o National Liberation Organization (PNLO) (6) All Burma Students Democratic Front (ABSDF) (7) Arakan Liberation Party (ALP) (8) Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS/Shan State Army-South (SSA-S) The Global New Light of Myanmar, 16 October 2016, Vol. II, No. 178 1 Media Monitoring Report – UNHCR Thailand Seven groups said that they are not ready to sign the NCA at the moment2. They are: (1) Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) (2) Kayinni National Progressive Party (KNPP) (3) National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) (4) New Mon State Party (NMSP) (5) National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Khaplang (NSCN-K) (6) Shan State Progressive Party/Shan State Army-North (SSPP/SSA-N) (7) United Wa State Army (UWSA). -

Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review of Myanmar July 2020 37Th Session of the UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council January/February 2021

Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review of Myanmar July 2020 37th Session of the UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council January/February 2021 Human Rights Violations in the Armed Conflicts in Arakan, Burma/Myanmar Submitted by: All Arakan Students’ and Youths’ Congress (AASYC) Contact: Mr. Ting Oo, General Secretary All Arakan Students’ and Youths’ Congress (AASYC) Email: [email protected] About All Arakan Students’ and Youths’ Congress (AASYC) All Arakan Students’ and Youths’ Congress (AASYC) is an independent and non-profit organization founded in October 6, 1995 in Bangkok, Thailand by the Arakanese students and youths who were exiled after the 1988 democracy uprising in Burma/Myanmar. AASYC works promote democracy and human rights of the Arakanese people in Arakan/Rakhine and beyond and to establish a genuine federal democratic union of Burma through non-violent means in collaboration with other democratic alliances in Burma/Myanmar. AASYC is a member organization of Students and Youth Congress of Burma (SYCB), Network for Human Rights Documentation (ND-Burma), Ethnic Community Development Forum (ECDF), Indigenous Peoples/Ethnic Nationalities of Myanmar (IPs/EN), Coalition of Indigenous People in Burma/Myanmar. Website: www.aasyc.info 1 A. Introduction 1. This submission was prepared for the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar in July, 2020. Within it, the All Arakan Students’ and Youths’ Congress (AASYC) evaluates the implementation of recommendations made to the Government of Myanmar (GoM) in its previous UPR, assesses the national human rights framework and the human rights situation on the ground, and makes a number of recommendations to the government of Myanmar to address the human rights challenges outlined in this report. -

“We Are Like Forgotten People”

“We Are Like Forgotten People” The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 2-56432-426-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org January 2009 2-56432-426-5 “We Are Like Forgotten People” The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India Map of Chin State, Burma, and Mizoram State, India .......................................................... 1 Map of the Original Territory of Ethnic Chin Tribes .............................................................. 2 I. Summary ......................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................... 7 II. Background .................................................................................................................... 9 Brief Political History of the Chin ................................................................................... -

Myanmar: Ethnic Politics and the 2020 General Election

MYANMAR POLICY BRIEFING | 23 | September 2020 Myanmar: Ethnic Politics and the 2020 General Election KEY POINTS • The 2020 general election is scheduled to take place at a critical moment in Myanmar’s transition from half a century under military rule. The advent of the National League for Democracy to government office in March 2016 was greeted by all the country’s peoples as the opportunity to bring about real change. But since this time, the ethnic peace process has faltered, constitutional reform has not started, and conflict has escalated in several parts of the country, becoming emergencies of grave international concern. • Covid-19 represents a new – and serious – challenge to the conduct of free and fair elections. Postponements cannot be ruled out. But the spread of the pandemic is not expected to have a significant impact on the election outcome as long as it goes ahead within constitutionally-appointed times. The NLD is still widely predicted to win, albeit on reduced scale. Questions, however, will remain about the credibility of the polls during a time of unprecedented restrictions and health crisis. • There are three main reasons to expect NLD victory. Under the country’s complex political system, the mainstream party among the ethnic Bamar majority always win the polls. In the population at large, a victory for the NLD is regarded as the most likely way to prevent a return to military government. The Covid-19 crisis and campaign restrictions hand all the political advantages to the NLD and incumbent authorities. ideas into movement • To improve election performance, ethnic nationality parties are introducing a number of new measures, including “party mergers” and “no-compete” agreements. -

CAUGHT in the CROSSFIRE: Witness and Survivor Accounts of Burma Army Attacks and Human Rights Violations in Arakan State

CAUGHT IN THE CROSSFIRE: Witness and Survivor Accounts of Burma Army Attacks and Human Rights Violations in Arakan State WARNING: This report contains graphic photos Caught in the Crossfire At right: Photos of victims of a Burma Army attack in Arakan State on April 13, 2020. For more information on this particular airstrike, please see the photo on page 9. Caught in the Crossfire Free Burma Rangers About this Report This report is the result of 178 interviews conducted, recorded, and translated by Arakan members of the Free Burma Rangers (FBR). The Rangers conducted the interviews during 2019 and submitted the translations and corresponding videos and photos in June 2020. These interviews represent a fraction of the total incidences of Burma Army abuse that is being perpetrated on a grand scale in Arakan State. In March 2020, the Burmese government designated the Arakan Army as a terrorist organization. With this designation, locals fear that the Burmese soldiers will increase the use of torture and detention against civilians in Arakan State with total impunity. Acknowledgements FBR would like to acknowledge and thank the Arakan Rangers for their hard work and dedication in collecting these interviews regarding the ongoing conflict in Arakan State. This report would not be possible without their commitment to getting the news out. We are also grateful to the witnesses who shared their stories and without whose courage in coming forward this report would not have been possible. FBR continues to stand with the Arakan people and others under attack in northern Arakan State as well as Chin State where this particular conflict has spilled into. -

“We Are Like Forgotten People” RIGHTS the Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India WATCH

Burma HUMAN “We Are Like Forgotten People” RIGHTS The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India WATCH “We Are Like Forgotten People” The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 2-56432-426-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org January 2009 2-56432-426-5 “We Are Like Forgotten People” The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India Map of Chin State, Burma, and Mizoram State, India .......................................................... 1 Map of the Original Territory of Ethnic Chin Tribes .............................................................