Arakan Army, AA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar: Conflicts and Human Rights Violations Continue to Cause Displacement

5 March 2009 Myanmar: Conflicts and human rights violations continue to cause displacement Displacement as a result of conflict and human rights violations continued in Myanmar in 2008. An estimated 66,000 people from ethnic minority communities in eastern Myanmar were forced to become displaced in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict and human rights abuses. As of October 2008, there were at least 451,000 people reported to be inter- nally displaced in the rural areas of eastern Myanmar. This is however a conservative fig- ure, and there is no information available on figures for internally displaced people (IDPs) in several parts of the country. In 2008, the displacement crisis continued to be most acute in Kayin (Karen) State in the east of the country where an intense offensive by the Myanmar army against ethnic insur- gent groups had been ongoing since late 2005. As of October 2008, there were reportedly over 100,000 IDPs in the state. New displacement was also reported in 2008 in western Myanmar’s Chin State as a result of human rights violations and severe food insecurity. People also continued to be displaced in some parts of the country due to a combination of coercive measures such as forced la- bour and land confiscation that left them with no choice but to migrate, often in the context of state-sponsored development initiatives. IDPs living in the areas of Myanmar still affected by armed conflict between the army and insurgent groups remained the most vulnerable, with their priority needs tending to be re- lated to physical security, food, shelter, health and education. -

Myanmar: the Country That ‘Has It All’

Journal of Southeast Asian Human Rights, Vol. 4 Issue. 1 June 2020 pp. 128 – 139 doi: 10.19184/jseahr.v4i1.17922 © University of Jember & Indonesian Consortium for Human Rights Lecturers Myanmar: the country that ‘has it all’ Susan Banki Department of Sociology and Social Policy - the University of Sydney Email: [email protected] Abstract For scholars of Southeast Asia interested in human rights, Myanmar is a country that ‘has it all.’ I use this tongue-in-cheek expression to suggest the myriad ways that the country remains mired in structural challenges that inform its current human rights problems. In this paper, I point out the country’s most glaring structural challenges and link these to its most pressing human rights problems. A brief section about Myanmar in the context of COVID-19 offers the same conclusion as the rest of the article: while there is variance in the actors targeted and the degree of suppression, the underlying patterns of oppression remain unchanged over time. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Nyi Nyi Kyaw for reviewing a draft of this paper and offering helpful comments. I. INTRODUCTION From its independence to the present day, one can look to Myanmar to observe multiple human rights trajectories, which today play out in myriad violations and responses in nearly all regions of the country. With natural resources of jade and teak, a rich cultural heritage with associated physical sites, and a central, if sandwiched, geopolitical location, one might imagine that the moniker I have given the country, ‘The country that has it all’ is a positive one. -

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Weekly Security Review

Weekly Security Review Safety and security highlights for clients operating in Myanmar Released: 06 February 2020 Dates covered: 29 January - 04 February 2020 The information in this report is correct as of 1800 hours (UTC+6:30) 04 February 2020. The contents of this report are subject to copyright and must not be reproduced or shared without approval from Exera. The information in this report is intended to inform and advise; any mitigation implemented as a result of this information is the responsibility of the client. Questions or requests for further information can be directed to [email protected]. Exera Weekly Review Client-in-Confidence Page 2 of 5 Armed Conflict Two (2) incidents have been reported in the last report period (29 January - 04 February 2020): 1. IED: 2nd Feb 2020 - Time: Unknown - Kayin State's Hpapun Township On 27 January, Tatmadaw Battalion Commander of Light Infantry Battalion No. 708 was killed in a targeted mine attack in Kayin State's Hpapun Township. According to a Tatmadaw spokesperson; the mine was planted by the Karen National Union's armed wing Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA). Photo via RFA Facebook page 2. IED: 3rd Feb 2020 - 07:00Hrs - Myawaddy Township, Kayin State Statements released by the Kayin State Border Guard Force; at approximately 07:00Hrs on Monday 3 Feb, 2x explosive devices detonated beside a residence in the 4th Quarter, near Asia Highway (AH-1) in Myawaddy Township, Kayin State. - Type of devices: Unconfirmed - Injuries: 2x Casualties (taken to Myawaddy Hospital) - Fatalities: Nil Reported - No group claimed responsibility for the attack - Authorities are conducting further investigations Assessment In 2014, intense skirmishes between the Tatmadaw and the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA) broke out on the outskirts of Myawaddy and a number of residents were displaced. -

New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State?

CRS INSIGHT New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State? February 15, 2019 (IN11046) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) Approximately 250 Chin and Rakhine refugees entered into Bangladesh's Bandarban district in the first week of February, trying to escape the fighting between Burma's military, or Tatmadaw, and one of Burma's newest ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the Arakan Army (AA). Bangladesh's Foreign Minister Abdul Momen summoned Burma's ambassador Lwin Oo to protest the arrival of the Rakhine refugees and the military clampdown in Rakhine State. Bangladesh has reportedly closed its border to Rakhine State. U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee released a press statement on January 18, 2019, indicating that heavy fighting between the AA and the Tatmadaw had displaced at least 5,000 people. She also called on the Rakhine State government to reinstate the access for international humanitarian organizations. The Conflict Between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw The AA was formed in Kachin State in 2009, with the support of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). In 2015, the AA moved some of its soldiers from Kachin State to southwestern Chin State, and began attacking Tatmadaw security bases in Chin State and northern Rakhine State (see Figure 1). In late 2017, the AA shifted more of its operations into northeastern Rakhine State. According to some estimates, the AA has approximately 3,000 soldiers based in Chin and Rakhine States. Figure 1. Reported Clashes between Arakan Army and Tatmadaw Source: CRS, utilizing data provided by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). -

Global Day of Prayer for 2020

GLOBAL DAY OFBURMA PRAYER FOR 2020 PRAYER AND ACTION BEYOND BORDERS:ZAU SENG, KACHIN MEDIC, VIDEOGRAPHER, AND FOLLOWER OF JESUS, GIVES HIS LIFE IN SYRIA 1 In this Issue Burma Overview 4 Burma Map 5 More Setbacks, Less Progress Stories of Love and Service 6 To Love is to Act 7 Show Another Way 11 North Star in a Dark Place Ethnic Area Updates 12 Arakan State 14 Chin State 15 Naga Hills 16 Northern Burma 18 Southern Shan State 19 Karenni State 20 Wa State 23 Karen State Praying For 24 Voices from Burma 26 Providing Care, Giving Hope 27 Justice Moves Forward 28 In Memoriam Pictured on this page: David Eubank and Pastor Edmund baptize one of five students who asked to be baptized at the conclusion of FBR training, December 2018. The Global Day of Prayer for Burma happens every year on the second Sunday of March. Please join us in praying for Burma. For more information, email [email protected]. Thanks to Acts Co. for its support and printing of this magazine. This magazine was produced by Christians Concerned for Burma (CCB). All text copyright CCB 2020. Design and layout by FBR Publications. All rights reserved. This magazine may be reproduced if proper credit is given to text and photos. All photos copyright Free Burma Rangers (FBR) unless otherwise noted. Scripture portions quoted are taken from the NIV unless otherwise noted. Christians Concerned for Burma (CCB), PO Box 392, Chiang Mai, 50000, THAILAND www.prayforburma.org [email protected] 2 As we see the innocent suffer and those who serve them die, it makes me ask: what difference does prayer make? I don’t know all the answers, but I do know that prayer changes my heart. -

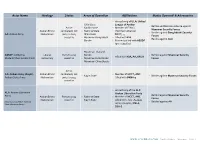

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma)

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Watchlist Mission Statement The Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict strives to end violations against children in armed conflicts and to guarantee their rights. As a global network, Watchlist builds partnerships among local, national and international nongovernmental organizations, enhancing mutual capacities and strengths. Working together, we strategically collect and disseminate information on violations against children in conflicts in order to influence key decision-makers to create and implement programs and policies that effectively protect children. Watchlist works within the framework of the provisions adopted in Security Council Resolutions 1261, 1314, 1379, 1460, 1539 and 1612, the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its protocols and other internationally adopted human rights and humanitarian standards. General supervision of Watchlist is provided by a Steering Committee of international nongovernmental organizations known for their work with children and human rights. The views presented in this report do not represent the views of any one organization in the network or the Steering Committee. For further information about Watchlist or specific reports, or to share information about children in a particular conflict situation, please contact: [email protected] www.watchlist.org Photo Credits Cover Photo: UNICEF/NYHQ2006- 1870/Robert Few Please Note: The people represented in the photos in this report are not necessarily themselves victims or survivors of human rights violations or other abuses. No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Notes on Methodology . Information contained in this report is current through January 1, 2009. -

Myanmar in 2020

MARIE-EVE RENY Myanmar in 2020 Citizens Have Voted for the Democratic Transition to Continue, but Democracy Remains Far Ahead Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/as/article-pdf/61/1/138/455584/as.2021.61.1.138.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 ABSTRACT The NLD was reelected in 2020 with more seats than it won in 2015. Myanmar’s transition is not regressing, but many priorities remain before the state truly democratizes: conducting transparent trials of military officers who were involved in the killings of Rohingyas, solving the conflict between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw in Rakhine State, ensuring that enduring armed conflicts do not undermine citizens’ ability to vote, making sure the National Ceasefire Agreement prevents the resurgence of old animosities, demilitarizing the constitution, and restraining the military’s ability to sue opposition for defamation. KEYWORDS: national elections, armed conflicts, conflict resolution, democratic transition, foreign policy ELECTIONS On November 8, 2020, Myanmar held its second democratic national elec- tions since the beginning of its political transition. The National League for Democracy (NLD) won a majority of seats it contested in the bicameral national legislature (399 of 476), and more seats than in 2015 (390). Its campaign priorities included reforming the constitution, creating a federa- tion, and conflict resolution with non-state armed groups. Most of its prior- ities were the same as in 2015. Although 87 parties competed in the elections, MARIE-EVE RENY is a Hundred Talents Researcher in the Department of Sociology, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. Her report is based on the Irrawaddy’s coverage of events in Myanmar in 2020, and to a limited extent, that of Frontier and Myanmar Times. -

Finding an Endgame in Kachin State the KIO’S Strategies for Finding a Resolution to the Conflict

EBO Background Paper - No .3 | 2018 September 2018 AUTHOR | Paul Keenan Finding an Endgame in Kachin State The KIO’s strategies for finding a resolution to the conflict Since 9 June 2011, Kachin State has seen open (CEFU). The Committee’s purpose was to conflict between the Kachin Independence Army consolidate a political front at a time when the and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military). The Kachin ceasefire groups faced perceived imminent attacks Independence Organisation had signed a ceasefire by the Tatmadaw. However, in November 2010 agreement with the regime in 1994 and since then shortly after the Myanmar elections, the political had lived in relative peace until the ceasefire was grouping was transformed into a military united broken by the Tatmadaw in June 2011. front. At a conference held from the 12-16 February 2011, CEFU declared its dissolution and the The increased territorial infractions by the formation of the United Nationalities Federal Tatmadaw combined with economic exploitation Council (UNFC). The UNFC, which was at that time by China in Kachin territory, especially the comprised of 12 ethnic organisations1, stated that: construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam, left the Kachin Independence Organisation with very The goal of the UNFC is to establish the little alternative but to return to armed resistance future Federal Union (of Myanmar) and to prevent further abuses of its people and their the Federal Union Army is formed for territory’s natural resources. Despite this, however, giving protection to the people of the the political situation since the beginning of country.2 hostilities has changed significantly. -

The Scramble for Rakhine

The Scramble for Rakhine Introduction Conflict in Myanmar today holds the track record of the longest civil war of our times. It is also one of the most complex, most protracted ones, involving some 20 armed groups struggling for autonomy, a history of failed attempts at building a nation from a multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-lingual population and a military accused of the most heinous of war crimes committed in the name of national unity. Hopes to find a peaceful settlement to the conflict were high when the military government initiated far-reaching reforms starting in 2011 which included the lifting of censorship and creation of space to political opposition. Finally, the democratic election of a quasi-civilian government under the leadership of Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, known worldwide for her vocal opposition to the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw), consolidated the optimism within the population. The socio-political reforms led to considerable improvements in Myanmar’s bilateral relations; International sanctions were lifted, and thanks to Myanmar’s largely untapped wealth in natural resources and its geostrategic position connecting South and Southeast Asia, the country quickly became a focus of policy- makers in Asia and beyond. Soon enough, the phenomenon came to be dubbed the ‘gold rush’ to Myanmar. Yet, Myanmar’s democratic transformation has failed to achieve peace. Four years into the new democratic government’s term in office, many ethnic groups suspect that Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy (NLD) are lacking a genuine will to address their communities’ grievances. As a result, new waves of violence swept the country soon after the NLD’s election.