International Actors in Myanmar's Peace Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Weekly Security Review

Weekly Security Review Safety and security highlights for clients operating in Myanmar Released: 06 February 2020 Dates covered: 29 January - 04 February 2020 The information in this report is correct as of 1800 hours (UTC+6:30) 04 February 2020. The contents of this report are subject to copyright and must not be reproduced or shared without approval from Exera. The information in this report is intended to inform and advise; any mitigation implemented as a result of this information is the responsibility of the client. Questions or requests for further information can be directed to [email protected]. Exera Weekly Review Client-in-Confidence Page 2 of 5 Armed Conflict Two (2) incidents have been reported in the last report period (29 January - 04 February 2020): 1. IED: 2nd Feb 2020 - Time: Unknown - Kayin State's Hpapun Township On 27 January, Tatmadaw Battalion Commander of Light Infantry Battalion No. 708 was killed in a targeted mine attack in Kayin State's Hpapun Township. According to a Tatmadaw spokesperson; the mine was planted by the Karen National Union's armed wing Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA). Photo via RFA Facebook page 2. IED: 3rd Feb 2020 - 07:00Hrs - Myawaddy Township, Kayin State Statements released by the Kayin State Border Guard Force; at approximately 07:00Hrs on Monday 3 Feb, 2x explosive devices detonated beside a residence in the 4th Quarter, near Asia Highway (AH-1) in Myawaddy Township, Kayin State. - Type of devices: Unconfirmed - Injuries: 2x Casualties (taken to Myawaddy Hospital) - Fatalities: Nil Reported - No group claimed responsibility for the attack - Authorities are conducting further investigations Assessment In 2014, intense skirmishes between the Tatmadaw and the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA) broke out on the outskirts of Myawaddy and a number of residents were displaced. -

Recent Arrests List

ƒ ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 8 of the Export and Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Lin of Special Branch President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s S: 25 of the Natural Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Naing law President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and parliament President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Union Assembly, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 5 (U) T Khun Myat M Joint House and Pyithu Hluttaw, the 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and lower house of the Myanmar President U Win Myint were detained. -

Arakan Army, AA)

Division de l’information, de la documentation et des recherches – DIDR 9 avril 2021 Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Armée de l’Arakan (Arakan Army, AA) Avertissement Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine, a été élaboré par la DIDR en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière et ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Arakan Army, (AA) Table des matières 1. Principales caractéristiques de l’Arakan Army ................................................................................ 3 1.1. Une organisation liée à la KIA et à l’UWSA ............................................................................. 3 1.2. Relations avec les autres organisations politico-militaires ...................................................... 3 2. Les opérations armées de l’AA ont entraîné des représailles massives ......................................... 4 3. Les interventions de l’AA à des fins logistiques dans les villages ................................................... 5 4. Enlèvements -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

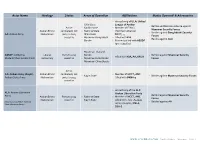

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

CONFLICT BAROMETER 2008 Crises - Wars - Coups D’Etat´ Negotiations - Mediations - Peace Settlements

HEIDELBERG INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT RESEARCH at the Department of Political Science, University of Heidelberg CONFLICT BAROMETER 2008 Crises - Wars - Coups d’Etat´ Negotiations - Mediations - Peace Settlements 17th ANNUAL CONFLICT ANALYSIS HIIK The HEIDELBERG INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT RESEARCH (HIIK) at the Department of Political Science, University of Heidelberg is a registered non-profit association. It is dedicated to research, evaluation and doc- umentation of intra- and interstate political conflicts. The HIIK evolved from the research project ’COSIMO’ (Conflict Simulation Model) led by Prof. Dr. Frank R. Pfetsch (University of Heidelberg) and financed by the German Research Association (DFG) in 1991. Conflict We define conflicts as the clashing of interests (positional differences) over national values of some duration and mag- nitude between at least two parties (organized groups, states, groups of states, organizations) that are determined to pursue their interests and achieve their goals. Conflict items Territory Secession Decolonization Autonomy System/ideology National power Regional predominance International power Resources Others Conflict intensities State of Intensity Level of Name of Definition violence group intensity intensity 1 Latent A positional difference over definable values of national meaning is considered conflict to be a latent conflict if demands are articulated by one of the parties and per- ceived by the other as such. Non-violent Low 2 Manifest A manifest conflict includes the use of measures that are located in the stage conflict preliminary to violent force. This includes for example verbal pressure, threat- ening explicitly with violence, or the imposition of economic sanctions. Medium 3 Crisis A crisis is a tense situation in which at least one of the parties uses violent force in sporadic incidents. -

2017 Myanmar By-Elections IEOM Report

1 2017 Myanmar By-Elections: A Path to Myanmar’s 2020 General Election Final Report of the International Election Observation Mission (IEOM) of the 2017 By-Elections in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar 2 Written by : Ryan D Whelan, Dr. Aulina Adamy, Amin Iskandar, Ichal Supriadi, Chandanie Watawala Edited by : Ryan D Whelan, George Rothschild, Karel J Galang Layout by : Sann Moe Aung Book cover designed by : Sann Moe Aung Printer : Mr.Print (Design & Printing) Photos without credits are courtesy of ANFREL mission observers The Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL) 105, Susthisarnwinichai Road, Samsennok, Huaykwang, Bangkok 10310, Thailand. Tel: (+66 2) 26931867 Email : [email protected] Website : www.anfrel.org ISBN : 978-616-90144-61 2017, Yangon, Myanmar This report reflects the holistic findings of the ANFREL Observation Mission in Myanmar and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of any of ANFREL’s individual observers, staff, donors, or CSO partners. No institution, nor a person acting on its behalf, shall be held responsible for the information contained herein. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. 3 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The mission would like to thank the committed International Election Observers, whose hard work informed the production of this report. Their dedication to both their observation and our democratic mission is an encouraging sign for democracy’s continued growth in Asia. ANFREL is similarly grateful for the dozens of local staff members who generously gave their time and energy to make the mission a success, often having to overcome significant challenges encountered along the way. ANFREL would also like to thank the Union Election Commission of Myanmar, government officials, as well as candidates and representatives of political parties, civil society groups, and the media in Myanmar for the warm welcome and cooperation provided to ANFREL and its observers. -

Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition

United Nations University Centre for Policy Research Crime-Conflict Nexus Series: No 9 April 2017 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition Dr. Vanda Felbab-Brown Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. © 2017 United Nations University. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-92-808-9040-2 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Myanmar case study analyzes the complex interactions between illegal economies -conflict and peace. Particular em- phasis is placed on understanding the effects of illegal economies on Myanmar’s political transitions since the early 1990s, including the current period, up through the first year of the administration of Aung San Suu Kyi. Described is the evolu- tion of illegal economies in drugs, logging, wildlife trafficking, and gems and minerals as well as land grabbing and crony capitalism, showing how they shaped and were shaped by various political transitions. Also examined was the impact of geopolitics and the regional environment, particularly the role of China, both in shaping domestic political developments in Myanmar and dynamics within illicit economies. For decades, Burma has been one of the world’s epicenters of opiate and methamphetamine production. Cultivation of poppy and production of opium have coincided with five decades of complex and fragmented civil war and counterinsur- gency policies. An early 1990s laissez-faire policy of allowing the insurgencies in designated semi-autonomous regions to trade any products – including drugs, timber, jade, and wildlife -- enabled conflict to subside. -

Data Collection Survey on the Project for Development of Water Saving Agricultural Technology in the Central Dry Zone in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar

Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation The Republic of the Union of Myanmar DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON THE PROJECT FOR DEVELOPMENT OF WATER SAVING AGRICULTURAL TECHNOLOGY IN THE CENTRAL DRY ZONE IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR FINAL REPORT AUGUST 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) SANYU CONSULTANTS INC. India China 51 Townships in the Central Dry Zone and Main Facilities of the Project Project Area Myanmar Yangon Thai Sagaing Region Myingyan DAR Center Mandalay Region Nyaung Oo DAR Center Magway DAR Center Magway Region Nay Pyi Taw Legend Border Border of Region Border of Township Project Area Division/ State Capital District Capital River Road Railway Photos of the Central Dry Zone Rainfed upland(before rainy season) Seeding at the beginning of rainy season Predominant sandy soil (before rainy season) Indian-made 4 wheel tractor Plowing by Power tiller Intercropping with groundnut and pigeon pea Intercropping with groundnut and maize Tube-well observed in Central Dry Zone Hydroponic irrigation (Magway Campus, Practice of the hydroponic irrigation in a Yezin Agricultural University ) village (Yenangyon) Practice of micro irrigation in a village Practice of micro irrigation in a (Yenangyon) village(Yenangyon) Dragon fruits (Mandalay) Bean Exchange market (Mandalay) Oil-extracting factory (Myingyan) Bean –processing factory (Myingyan) CONTENTS Location Map of the Study Area Photos of the Central Dry Zone CHAPTER 1 BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES ············································ 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... -

PEACE Info (March 16, 2018)

PEACE Info (March 16, 2018) − Myanmar’s Karen Cease-Fire in Jeopardy − New Mon State Party faces birthing pains after signing ceasefire pact − Negotiation, not coercion, offers best hope of peace in Kachin − Press briefings to be held to reduce local concerns over fighting between NMSP and KNU − Tatmadaw Offensive Forces KIA Battalion to Abandon Base in Tanai − Two civilians killed as RCSS-TNLA fighting flares again − Confiscated land returned to farmers − Myanmar returns confiscated land to farmers in eastern state − ၿငိမ္းခ်မ္းေရးျမန္ဆန္သြက္လက္ရန္ အစိုးရႏွင့္တပ္မေတာ္ညႇိႏွိုင္းမွုမ်ားလိုအပ္ဟု ဦးခြန္ဥကၠာသုံးသပ္ − အမ်ဳိးသားအဆင့္ ႏိုင္ငံေရးေဆြးေႏြးပြဲမ်ား မက်င္းပႏုိင္ျခင္းက ၿငိမ္းခ်မ္းေရးလုပ္ငန္းစဥ္ အခက္အခဲျဖစ္ဟု ေကအင္န္ယူ ဒုဥကၠ႒ေျပာ − မြန္ျပည္သစ္ပါတီႏွင့္ KNU ပဋိပကၡထပ္မံမျဖစ္ပြားေရး နည္းလမ္းႏွစ္ခုျဖင့္ ေဆာင္ရြက္မည္ − စစ္ေရးအေျခအေနေၾကာင့္ တႏုိင္းေဒသအေျခစိုက္ ေကအိုင္ေအတပ္ရင္း (၁၄) ေနရာေျပာင္းေရႊ႕ − လမ္းေဖါက္ေနတဲ့တပ္ေတြ ဆုတ္ေပးဖို႔ KNU ေတာင္းဆို − ေကအန္ယူ ထိပ္ပိုင္းေခါင္းေဆာင္ေတြ အေရးေပၚအစည္းအေဝးလုပ္ − အစုိးရတပ္မ်ား ဖာပြန္ခ႐ုိင္တြင္းမွ ျပန္႐ုပ္သိမ္းရန္ ေကအန္ယူ ေတာင္းဆုိ − ဖာပြန္ခရိုင္အတြင္းရိွ အစိုးရတပ္မ်ား ျပန္လည္ဆုတ္ခြာေပးရန္ KNU ေတာင္းဆို − တပ္မေတာ္အေနျဖင့္ နယ္ေျမအတြင္း စစ္ေရးလႈပ္ရွားမႈမ်ားကုိ ရပ္ဆုိင္းရန္ KNU ေျပာ − ဖာပြန္ခရိုင္မွာ တပ္မေတာ္က KNU စစ္ေဆးေရးဂိတ္ကို မီးရိႈ႕ − တပ္မေတာ္ႏွင့္ ေကအန္အယ္လ္ေအ တုိက္ပြဲျဖစ္၊ ေကအန္အယ္လ္ေအတပ္စခန္း ဖ်က္ဆီးခံရ − RCSS ႏွင့္ TNLA တိုက္ပြဲၾကားက ေဒသခံမ်ား မိုင္းအႏၲရာယ္ေၾကာင့္ ကယ္မထုတ္နိုင္ေသး − တိုက္ပြဲအတြင္းပိတ္မိေနေသာ အရပ္သားမ်ားကို ကယ္ထုတ္ႏိုင္ေရး အရပ္ဘက္အဖြဲ႕မ်ား ႀကိဳးစားမႈ မေအာင္ျမင္ − RCSS ႏွင့္ TNLA -

Recent Arrests List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 8 of the Export and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Import Law and S: 25 Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and of the Natural Disaster Lin of Special Branch regions were also detained. Management law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 25 of the Natural President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and Naing law regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and parliament regions were also detained.