A Within-Case Analysis of Burma/Myanmar, 1948-2011 Alexa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

The Situation in Karen State After the Elections PAPER No

EBO ANALYSIS The Situation in Karen State after the Elections PAPER No. 1 2011 THE SITUATION IN KAREN STATE AFTER THE ELECTIONS EBO Analysis Paper No. 1/2011 For over sixty years the Karens have been fighting the longest civil war in recent history. The struggle, which has seen demands for an autonomous state changed to equal recognition within a federal union, has been bloody and characterized by a number of splits within the movement. While all splinter groups ostensibly split to further ethnic Karen aspirations; recent decisions by some to join the Burmese government’s Border Guard Force (BGF) is seen as an end to such aspirations. Although a number of Karen political parties were formed to contest the November elections, the likelihood of such parties seriously securing appropriate ethnic representation without regime capitulation is doubtful. While some have argued, perhaps correctly, that the only legitimate option was to contest the elections, the closeness of some Karen representatives to the current regime can only prolong the status quo. This papers examines the problems currently affecting Karen State after the 7 November elections. THE BORDER GUARD FORCE Despite original promises of being allowed to recruit a total of 9,000 troops, the actual number of the DKBA (Democratic Karen Buddhist Army) or Karen Border Guard Force has been reduced considerably. In fact, a number of the original offers made to the DKBA have been revoked. At a 7 May 2010 meeting held at Myaing Gyi Ngu, DKBA Chairman U Tha Htoo Kyaw stated that ‘According to the SE Commander, the BGF will retain the DKBA badge.’ In fact the DKBA were given uniforms with SPDC military patches and all Karen flags in DKBA areas were removed and replaced by the national flag. -

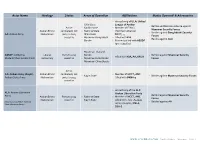

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

Karen Refugees from Burma in the US: an Overview for Torture Treatment Programs Presentation by Eh Taw Dwe and Tonya Cook Caveat “Karen People Are Very Diverse

Karen Refugees from Burma in the US: an Overview for Torture Treatment Programs Presentation by Eh Taw Dwe and Tonya Cook Caveat “Karen people are very diverse. Among the Karen people there are different languages, different cultures, different religions, and different political groups. No one can claim to speak on behalf of all Karen people, or represent all Karen people.” - Venerable Ashin Moonieinda From “The Karen people: Culture, Faith and History.” (http://www.karen.org.au/docs/karen_people.pdf) Introduction to Burma - January 4th, 1948 –independence - Government type = Military Junta. A brutal military regime has been in power since 1962. - The junta allowed “elections” to be held in Burma in 1990. - The National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi won over 80% of the vote. The list of party candidates became the hit list of the junta. The NLD was never allowed to claim their rightful seats. Burma or Myanmar? •The military dictatorship changed the name of Burma to Myanmar in 1989. • Parties who do not accept the authority of the unelected military regime to change the official name of the country still call it Burma (minority ethnic groups, the U.S. and the UK. •The UN, France, and Japan recognize it as Myanmar. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7013943.stm Who Lives in Burma? There are eight main ethnic groups and 130 distinct sub-groups Total Population = ~55 Million Includes: •Burmans = 37.4 Million (68%) •Karen in Burma = 7 to 9 Million •Karen in Thailand = 400,000 •Karen in Thai refugee camps= ~150,000 Source: http://www.cal.org/co/pdffiles/refugeesfromburma.pdf Map courtesy of Free Burma Rangers Kachin Karenni Chin Mon Rakhine (Arakanese) Shan Burman Karen Map of the Karen State How to Refer to Refugees from Burma There is no single national identity. -

Finding an Endgame in Kachin State the KIO’S Strategies for Finding a Resolution to the Conflict

EBO Background Paper - No .3 | 2018 September 2018 AUTHOR | Paul Keenan Finding an Endgame in Kachin State The KIO’s strategies for finding a resolution to the conflict Since 9 June 2011, Kachin State has seen open (CEFU). The Committee’s purpose was to conflict between the Kachin Independence Army consolidate a political front at a time when the and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military). The Kachin ceasefire groups faced perceived imminent attacks Independence Organisation had signed a ceasefire by the Tatmadaw. However, in November 2010 agreement with the regime in 1994 and since then shortly after the Myanmar elections, the political had lived in relative peace until the ceasefire was grouping was transformed into a military united broken by the Tatmadaw in June 2011. front. At a conference held from the 12-16 February 2011, CEFU declared its dissolution and the The increased territorial infractions by the formation of the United Nationalities Federal Tatmadaw combined with economic exploitation Council (UNFC). The UNFC, which was at that time by China in Kachin territory, especially the comprised of 12 ethnic organisations1, stated that: construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam, left the Kachin Independence Organisation with very The goal of the UNFC is to establish the little alternative but to return to armed resistance future Federal Union (of Myanmar) and to prevent further abuses of its people and their the Federal Union Army is formed for territory’s natural resources. Despite this, however, giving protection to the people of the the political situation since the beginning of country.2 hostilities has changed significantly. -

Burma's Longest

TRANSNATIONAL I N S T I T U T E B URMA C ENTER N ETHERLANDS Burma’s Longest WAR ANATOMY OF THE KAREN CONFLICT Ashley South 3 Burma’s Longest War - Anatomy of the Karen Conflict Author Ashley South Copy Editor Nick Buxton Design Guido Jelsma, www.guidojelsma.nl Photo credits Hans van den Bogaard (HvdB) Tom Kramer (TK) Free Burma Rangers (FBR). Cover Photo Karen Don Dance (TK) Printing Drukkerij PrimaveraQuint Amsterdam Contact Transnational Institute (TNI) PO Box 14656, 1001 LD Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: +31-20-6626608 Fax: +31-20-6757176 e-mail: [email protected] www.tni.org/work-area/burma-project Burma Center Netherlands (BCN) PO Box 14563, 1001 LB Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: +31-20-671 6952 Fax: +31-20-6713513 e-mail: [email protected] www.burmacentrum.nl Ashley South is an independent writer and consultant, specialising in political issues in Burma/Myanmar and Southeast Asia [www.ashleysouth.co.uk]. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank all those who helped with the research, and commented on various drafts of the report. Thanks to Martin Smith, Tom Kramer, Alan Smith, David Eubank, Amy Galetzka, Monique Skidmore, Hazel Laing, Mandy Sadan, Matt Finch, Nils Carstensen, Mary Callahan, Ardeth Thawnghmung, Richard Horsey, Zunetta Liddell, Marie Lall, Paul Keenan and Miles Jury, and to many people in and from Burma, who cannot be acknowledged for security reasons. Thanks as ever to Bellay Htoo and the boys for their love and support. Amsterdam, March 2011 4 Contents Executive Summary 2 Humanitarian Issues 30 MAP 1: Burma -

CONFLICT BAROMETER 2008 Crises - Wars - Coups D’Etat´ Negotiations - Mediations - Peace Settlements

HEIDELBERG INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT RESEARCH at the Department of Political Science, University of Heidelberg CONFLICT BAROMETER 2008 Crises - Wars - Coups d’Etat´ Negotiations - Mediations - Peace Settlements 17th ANNUAL CONFLICT ANALYSIS HIIK The HEIDELBERG INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT RESEARCH (HIIK) at the Department of Political Science, University of Heidelberg is a registered non-profit association. It is dedicated to research, evaluation and doc- umentation of intra- and interstate political conflicts. The HIIK evolved from the research project ’COSIMO’ (Conflict Simulation Model) led by Prof. Dr. Frank R. Pfetsch (University of Heidelberg) and financed by the German Research Association (DFG) in 1991. Conflict We define conflicts as the clashing of interests (positional differences) over national values of some duration and mag- nitude between at least two parties (organized groups, states, groups of states, organizations) that are determined to pursue their interests and achieve their goals. Conflict items Territory Secession Decolonization Autonomy System/ideology National power Regional predominance International power Resources Others Conflict intensities State of Intensity Level of Name of Definition violence group intensity intensity 1 Latent A positional difference over definable values of national meaning is considered conflict to be a latent conflict if demands are articulated by one of the parties and per- ceived by the other as such. Non-violent Low 2 Manifest A manifest conflict includes the use of measures that are located in the stage conflict preliminary to violent force. This includes for example verbal pressure, threat- ening explicitly with violence, or the imposition of economic sanctions. Medium 3 Crisis A crisis is a tense situation in which at least one of the parties uses violent force in sporadic incidents. -

Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition

United Nations University Centre for Policy Research Crime-Conflict Nexus Series: No 9 April 2017 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition Dr. Vanda Felbab-Brown Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. © 2017 United Nations University. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-92-808-9040-2 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Myanmar case study analyzes the complex interactions between illegal economies -conflict and peace. Particular em- phasis is placed on understanding the effects of illegal economies on Myanmar’s political transitions since the early 1990s, including the current period, up through the first year of the administration of Aung San Suu Kyi. Described is the evolu- tion of illegal economies in drugs, logging, wildlife trafficking, and gems and minerals as well as land grabbing and crony capitalism, showing how they shaped and were shaped by various political transitions. Also examined was the impact of geopolitics and the regional environment, particularly the role of China, both in shaping domestic political developments in Myanmar and dynamics within illicit economies. For decades, Burma has been one of the world’s epicenters of opiate and methamphetamine production. Cultivation of poppy and production of opium have coincided with five decades of complex and fragmented civil war and counterinsur- gency policies. An early 1990s laissez-faire policy of allowing the insurgencies in designated semi-autonomous regions to trade any products – including drugs, timber, jade, and wildlife -- enabled conflict to subside. -

Hpa-An District: Fighting Between the Tatmadaw/BGF And

News Bulletin September 12th, 2020 / KHRG #20-5-NB1 Hpa-an District: Fighting between the Tatmadaw/BGF and the DKBA splinter group results in temporary displacement and restrictions to freedom of movement in T’Nay Hsah Township, September 2020 On September 4th 2020, fighting broke out between the Tatmadaw/BGF and the DKBA splinter group near Yaw Kuh village, Yaw Kuh village tract, T’Nay Hsah [Nabu] Township, Hpa-an District. The fighting ultimately spread to other villages in nearby village tracts, prompting local villagers to flee out of fear of being arrested as porters. The increased presence of BGF soldiers in nearby areas has also resulted in restrictions to freedom of movement for local civilians.1 Fighting between the Tatmadaw/BGF and the DKBA splinter group On September 4th 2020 at around 3:30 PM, fighting broke out between the Tatmadaw2 Light Infantry BattaLion #230, supported by Border Guard Force [BGF]3 BattaLion #1017, and a splinter faction of the Democratic Karen BenevoLent Army [DKBA splinter group]4 near Yaw Kuh viLLage, Yaw Kuh viLLage tract, T’Nay Hsah Township, Hpa-an District. The LocaL viLLagers stated that the fighting lasted for around 25 minutes. On the incident day, the BGF and the Tatmadaw also entered Yaw Kuh viLLage and fired at other armed groups based nearby, incLuding the KNU/KNLA-Peace CounciL [KNU/KNLA-PC]5 and the Karen NationaL Liberation Army [KNLA].6 This amounts to a vioLation of section 5(a) of the 1 The present document is based on information received in September 7th 2020. -

Recent Conflict in Karen State

EBO B ackground Paper NO. 5 / 2016 November 2016 AUTHOR | Paul Keenan Questionable Legitimacy: Recent Conflict in Karen State In September 2016, over 4,000 Karen civilians were forced to flee from their homes due to fighting between a break away Democratic Karen Benevolent Army faction and the Myanmar Army’s Border Guard Force (BGF) in the Mae Tha Waw area of Karen (Kayin) State. Fighting by the group, which has resurrected the name Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA)1 and has sworn allegiance to U Thuzana, the Myaing Gyi Ngu Sayadaw,2 has been characterised by a number of commentators as being nationalist in nature. However, the origins of the group, and their objectives, do not necessarily support such a hypothesis. Instead it further illustrates the confusion over the perceived ethno- nationalist conflict of some Karen groups and those that are seeking to perpetuate their own existence at a cost to the local population. Democratic Karen Buddhist Army – Kyaw Htet (DKBA-KH) There are primarily three distinct entities that currently comprise the current DKBA-KH faction.3 The first two are based in Hlaingbwe Township and commanded by Kyaw Htet and Bo Bi (aka Saw Taing Shwe), while the other, led by San Aung, previously from the DKBA’s 907 Battalion, is based further south in Kawkareik.4 Little is known about the actual structure or chain of command but all three groups appear to be operating individually and are funded through the extortion and taxation of villagers and local trade. Each group is estimated to have between 60-70 troops.