Recent Conflict in Karen State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

The Situation in Karen State After the Elections PAPER No

EBO ANALYSIS The Situation in Karen State after the Elections PAPER No. 1 2011 THE SITUATION IN KAREN STATE AFTER THE ELECTIONS EBO Analysis Paper No. 1/2011 For over sixty years the Karens have been fighting the longest civil war in recent history. The struggle, which has seen demands for an autonomous state changed to equal recognition within a federal union, has been bloody and characterized by a number of splits within the movement. While all splinter groups ostensibly split to further ethnic Karen aspirations; recent decisions by some to join the Burmese government’s Border Guard Force (BGF) is seen as an end to such aspirations. Although a number of Karen political parties were formed to contest the November elections, the likelihood of such parties seriously securing appropriate ethnic representation without regime capitulation is doubtful. While some have argued, perhaps correctly, that the only legitimate option was to contest the elections, the closeness of some Karen representatives to the current regime can only prolong the status quo. This papers examines the problems currently affecting Karen State after the 7 November elections. THE BORDER GUARD FORCE Despite original promises of being allowed to recruit a total of 9,000 troops, the actual number of the DKBA (Democratic Karen Buddhist Army) or Karen Border Guard Force has been reduced considerably. In fact, a number of the original offers made to the DKBA have been revoked. At a 7 May 2010 meeting held at Myaing Gyi Ngu, DKBA Chairman U Tha Htoo Kyaw stated that ‘According to the SE Commander, the BGF will retain the DKBA badge.’ In fact the DKBA were given uniforms with SPDC military patches and all Karen flags in DKBA areas were removed and replaced by the national flag. -

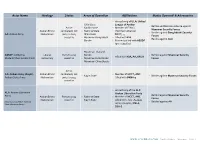

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

Karen Refugees from Burma in the US: an Overview for Torture Treatment Programs Presentation by Eh Taw Dwe and Tonya Cook Caveat “Karen People Are Very Diverse

Karen Refugees from Burma in the US: an Overview for Torture Treatment Programs Presentation by Eh Taw Dwe and Tonya Cook Caveat “Karen people are very diverse. Among the Karen people there are different languages, different cultures, different religions, and different political groups. No one can claim to speak on behalf of all Karen people, or represent all Karen people.” - Venerable Ashin Moonieinda From “The Karen people: Culture, Faith and History.” (http://www.karen.org.au/docs/karen_people.pdf) Introduction to Burma - January 4th, 1948 –independence - Government type = Military Junta. A brutal military regime has been in power since 1962. - The junta allowed “elections” to be held in Burma in 1990. - The National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi won over 80% of the vote. The list of party candidates became the hit list of the junta. The NLD was never allowed to claim their rightful seats. Burma or Myanmar? •The military dictatorship changed the name of Burma to Myanmar in 1989. • Parties who do not accept the authority of the unelected military regime to change the official name of the country still call it Burma (minority ethnic groups, the U.S. and the UK. •The UN, France, and Japan recognize it as Myanmar. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7013943.stm Who Lives in Burma? There are eight main ethnic groups and 130 distinct sub-groups Total Population = ~55 Million Includes: •Burmans = 37.4 Million (68%) •Karen in Burma = 7 to 9 Million •Karen in Thailand = 400,000 •Karen in Thai refugee camps= ~150,000 Source: http://www.cal.org/co/pdffiles/refugeesfromburma.pdf Map courtesy of Free Burma Rangers Kachin Karenni Chin Mon Rakhine (Arakanese) Shan Burman Karen Map of the Karen State How to Refer to Refugees from Burma There is no single national identity. -

Finding an Endgame in Kachin State the KIO’S Strategies for Finding a Resolution to the Conflict

EBO Background Paper - No .3 | 2018 September 2018 AUTHOR | Paul Keenan Finding an Endgame in Kachin State The KIO’s strategies for finding a resolution to the conflict Since 9 June 2011, Kachin State has seen open (CEFU). The Committee’s purpose was to conflict between the Kachin Independence Army consolidate a political front at a time when the and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military). The Kachin ceasefire groups faced perceived imminent attacks Independence Organisation had signed a ceasefire by the Tatmadaw. However, in November 2010 agreement with the regime in 1994 and since then shortly after the Myanmar elections, the political had lived in relative peace until the ceasefire was grouping was transformed into a military united broken by the Tatmadaw in June 2011. front. At a conference held from the 12-16 February 2011, CEFU declared its dissolution and the The increased territorial infractions by the formation of the United Nationalities Federal Tatmadaw combined with economic exploitation Council (UNFC). The UNFC, which was at that time by China in Kachin territory, especially the comprised of 12 ethnic organisations1, stated that: construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam, left the Kachin Independence Organisation with very The goal of the UNFC is to establish the little alternative but to return to armed resistance future Federal Union (of Myanmar) and to prevent further abuses of its people and their the Federal Union Army is formed for territory’s natural resources. Despite this, however, giving protection to the people of the the political situation since the beginning of country.2 hostilities has changed significantly. -

Burma's Longest

TRANSNATIONAL I N S T I T U T E B URMA C ENTER N ETHERLANDS Burma’s Longest WAR ANATOMY OF THE KAREN CONFLICT Ashley South 3 Burma’s Longest War - Anatomy of the Karen Conflict Author Ashley South Copy Editor Nick Buxton Design Guido Jelsma, www.guidojelsma.nl Photo credits Hans van den Bogaard (HvdB) Tom Kramer (TK) Free Burma Rangers (FBR). Cover Photo Karen Don Dance (TK) Printing Drukkerij PrimaveraQuint Amsterdam Contact Transnational Institute (TNI) PO Box 14656, 1001 LD Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: +31-20-6626608 Fax: +31-20-6757176 e-mail: [email protected] www.tni.org/work-area/burma-project Burma Center Netherlands (BCN) PO Box 14563, 1001 LB Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: +31-20-671 6952 Fax: +31-20-6713513 e-mail: [email protected] www.burmacentrum.nl Ashley South is an independent writer and consultant, specialising in political issues in Burma/Myanmar and Southeast Asia [www.ashleysouth.co.uk]. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank all those who helped with the research, and commented on various drafts of the report. Thanks to Martin Smith, Tom Kramer, Alan Smith, David Eubank, Amy Galetzka, Monique Skidmore, Hazel Laing, Mandy Sadan, Matt Finch, Nils Carstensen, Mary Callahan, Ardeth Thawnghmung, Richard Horsey, Zunetta Liddell, Marie Lall, Paul Keenan and Miles Jury, and to many people in and from Burma, who cannot be acknowledged for security reasons. Thanks as ever to Bellay Htoo and the boys for their love and support. Amsterdam, March 2011 4 Contents Executive Summary 2 Humanitarian Issues 30 MAP 1: Burma -

Hpa-An District: Fighting Between the Tatmadaw/BGF And

News Bulletin September 12th, 2020 / KHRG #20-5-NB1 Hpa-an District: Fighting between the Tatmadaw/BGF and the DKBA splinter group results in temporary displacement and restrictions to freedom of movement in T’Nay Hsah Township, September 2020 On September 4th 2020, fighting broke out between the Tatmadaw/BGF and the DKBA splinter group near Yaw Kuh village, Yaw Kuh village tract, T’Nay Hsah [Nabu] Township, Hpa-an District. The fighting ultimately spread to other villages in nearby village tracts, prompting local villagers to flee out of fear of being arrested as porters. The increased presence of BGF soldiers in nearby areas has also resulted in restrictions to freedom of movement for local civilians.1 Fighting between the Tatmadaw/BGF and the DKBA splinter group On September 4th 2020 at around 3:30 PM, fighting broke out between the Tatmadaw2 Light Infantry BattaLion #230, supported by Border Guard Force [BGF]3 BattaLion #1017, and a splinter faction of the Democratic Karen BenevoLent Army [DKBA splinter group]4 near Yaw Kuh viLLage, Yaw Kuh viLLage tract, T’Nay Hsah Township, Hpa-an District. The LocaL viLLagers stated that the fighting lasted for around 25 minutes. On the incident day, the BGF and the Tatmadaw also entered Yaw Kuh viLLage and fired at other armed groups based nearby, incLuding the KNU/KNLA-Peace CounciL [KNU/KNLA-PC]5 and the Karen NationaL Liberation Army [KNLA].6 This amounts to a vioLation of section 5(a) of the 1 The present document is based on information received in September 7th 2020. -

KNU Land Policy

OFFICE OF THE SUPREME HEADQUARTERS KAREN NATIONAL UNION KAWTHOOLEI Karen National Union – KNU Land Policy December 2015 OFFICE OF THE SUPREME HEADQUARTERS KAREN NATIONAL UNION KAWTHOOLEI Karen National Union – KNU Land Policy December 2015 Table of Contents PREAMBLE ........................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1: PRELIMINARY ............................................................5 Article 1.1 Basic Principle of Kawthoolei Land Policy ................5 Article 1.2 Objectives ..................................................................6 Article 1.3 Nature and scope ......................................................8 Article 1.4 Definitions ..................................................................9 CHAPTER 2: GENERAL POLICY MATTERS .................................16 Article 2.1 Basic principles ........................................................16 Article 2.2 Principles of implementation ...................................18 Article 2.3 Rights and responsibilities .......................................20 Article 2.4 Policy, legal and organizational frameworks related to land governance ......................................................22 CHAPTER 3: RECOGNITION AND ALLOCATION OF TENURE RIGHTS AND DUTIES .............................................................25 Article 3.1 Basic principles ........................................................25 Article 3.2 Safeguards ..............................................................26 Article 3.3 “Kaw” -

Myanmar Issue Brief No

CHINA, THE UNITED STATES AND THE KACHIN CONFLICT GREAT POWERS AND THE CHANGING MYANMAR ISSUE BRIEF NO. 2 JANUARY 2014 [UPDATED] China, the United States and the Kachin Conflict By Yun Sun This issue brief examines the development of the Kachin conflict in northern Myanmar’s Kachin and Shan states, the negotiations between the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) and the Myan- mar government, and the roles China and the United States have played in the conflict. KEY FINDINGS: 1 The prolonged Kachin conflict is a 3 The disagreements on terms have 5 Promoting national peace and major obstacle to Myanmar’s national hindered a formal cease-fire. In ad- reconciliation is a pillar of the US reconciliation and a challenging test dition, the existing economic inter- policy toward Myanmar. However, the for the democratization process. est groups profiting from the armed United States is being very careful not conflict have further undermined the to impose itself into the peace process prospect for progress. itself, including Kachin talks, given 2 The KIO and the Myanmar the government’s sensitivity that the government differ on the priority process remains an internal affair of between the cease-fire and the political 4 China intervened in the Kachin ne- the country. dialogue. Without addressing this gotiations in 2013 to protect its national difference, the nationwide peace interests. A crucial motivation was a accord proposed by the government concern about the “internationaliza- will most likely lack the KIO’s tion” of the Kachin issue and the poten- participation. tial US role along the Chinese border. -

NEITHER WAR NOR PEACE the FUTURE of the CEASE-FIRE AGREEMENTS in BURMA Main Armed Groups in Nothern Burma

TRANSNATIONAL I N S T I T U T E NEITHER WAR NOR PEACE THE FUTURE OF THE CEASE-FIRE AGREEMENTS IN BURMA Main armed groups in nothern Burma. Areas are approximate, status of some groups changed groups some of status approximate, are Areas Burma. in nothern groups armed Main Author Printing Contact: Tom Kramer Drukkerij PrimaveraQuint Transnational Institute Amsterdam De Wittenstraat 25 Copy editor 1052 AK Amsterdam David Aronson Financial Contributions Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs Tel: 31-20-6626608 Design (Netherlands) Fax: 31-20-6757176 Guido Jelsma [email protected] www.tni.org Photo credits Tom Kramer The contents of this document can be quoted or reproduced as long as the source is mentioned. TNI would appreciate receiving a copy of the text in which this document is used or cited. To receive information about TNI’s publications and activities, we suggest that you subscribe to our bi-weekly bulletin by sending a request to: [email protected] or registering at www.tni.org Amsterdam, July 2009 Contents Introduction 2 Burma: Ethnic Conflict and Military Rule 4 The Cease-fire Economy 24 Conflict Actors 4 Infrastructure 24 Independence and Civil War 5 Trade and Investment 25 Military Rule 6 Mono-Plantations 25 Cold War Alliances 7 Investment from Abroad 25 The Democracy Movement 7 Logging 26 Mining 27 The Making of the Cease-fire Agreements 8 Drugs Trade 27 The Fall of the CPB 8 The First Round of Crease-fires 9 International Responses to the Cease-fires 30 The NDF and the Second Round of Cease-fires 9 The Role of Neighbouring Countries -

Conflict and Politics in Burma

Appendices: Background / 13 Appendix I: Conflict and Politics in Burma APPENDICES: BACKGROUND downplayed ethnic differences. This policy of cultural assimilation has only served to create 13 APPENDIX I: CONFLICT AND resentment amongst the ethnic groups. POLITICS IN BURMA The road map to independence was finalised at the Panglong Conference in February 1947. Under “The conflict in Burma is deep rooted. Solutions can only be this agreement the Frontier Areas were guaranteed found if the real issues of conflict are examined, such as “full autonomy in internal administration”273 and the territory, resources and nationality…”270 Dr Chao-Tzang 274 Yawnghwe, Burmese academic, December 2001 enjoyment of democratic “rights and privileges”. Elections held later in 1947 were won by the Anti- Burma’s position between China and India is of key Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), but were strategic importance being at the crossroads of Asia, boycotted by the Karen National Union and the where south, east and Southeast Asia meet. Rugged CPB,jj amongst others.275 Nevertheless, a mountain ranges form a horseshoe surrounding the constitution was drafted that aimed to create a sense fertile plains of the Irrawaddy River. In the far north, of Burmese identity and cohesiveness, whilst the 1,463 km border with China follows the line of enshrining ethnic rights and aspirations for self- the Gaoligongshan Mountains.271 These remote determination.276 However, the constitution failed to border areas are rich in natural resources including deal with the ethnic groups even-handedly and did timber, but the benefits derived from this natural not adequately address separatist concerns. -

A Within-Case Analysis of Burma/Myanmar, 1948-2011 Alexa

Why Do Some Insurgent Groups Agree to Ceasefires While Others Do Not? A Within-Case Analysis of Burma/Myanmar, 1948-2011 Alexander Dukalskis University College Dublin [email protected] Final version published in Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38(10): 841-863. Please cite final published version of article. Abstract: This article uses Burma/Myanmar from 1948 to 2011 as a within-case analysis to explore why some armed insurgent groups agree to ceasefires while others do not. Analyzing 33 armed groups it finds that longer-lived groups were less likely to agree to ceasefires with the military government between 1989 and 2011. The article uses this within-case variation to understand what characteristics would make an insurgent group more or less likely to agree to a ceasefire. The article identifies four armed groups for more in-depth qualitative analysis to understand the roles of the administration of territory, ideology, and legacies of distrust with the state as drivers of the decision to agree to or reject a ceasefire. Running head: Ceasefires in Burma/Myanmar 1 Between independence from Britain in 1948 and a tentative transition to a less militaristic regime in 2011, the central government of Burma/Myanmar had to contend with dozens of armed insurgent groups. Over time new groups formed, old ones were defeated or gave up, and existing ones changed demands, allied with each other, splintered from parent insurgencies or changed form. During this period the central government presented itself to the armed insurgents in at least four different forms: a weak parliamentary regime (1948-1958), a military ‘caretaker’ government (1958-1960), a socialist-military regime (1962-1988) and a military junta (1988-2011).