Ceasefires, Governance and Development: the Karen National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Outline of the History of the Communist Party of Burma

A SHORT OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF .· THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF BURMA I Burma was an independent kingdom before annexation by the British imperialist in 1824. In 1885 British imperialist annexed whole of Burma. Since that time, Burmese people have never given up their fight for regaining their independence. Various armed uprisings and other legal forms of strug gle were used by the Burmese people in their fight to regain indep~ndence. In 19~8 the biggest and the broadest anti-British general _strike over-ran the whole country. The workers were on strike, the peasants marched up to Rangoon and all the students deserted their class-room to join the workers and peasants. It was an unprecendented anti-British movement in Burma popularly called in Burmese as "1300th movement". Out of this national and class struggle of the Burmese people and working class emerges the Communist Party of Burma. II The Communist Party of Burma was of!i~ially founded on 15th ~_!l_g~s_b 1939 by _!!nitil)K all MarxisLgr.9J!l!§ in Burma, III From the day of inception, CPB launched an active anti-British struggles up till 1941. It was the core of CPB leadership that led ahti British struggles up till the second world war. IV In 1941, after the Hitlerites treacherously attacked the Soviet Union, CPB changed its tactics and directed its blows against the fascists. v In 1942, Burma was invaded by the Japanese fascists. From that time onwards up till 1945, CPB worked unt~ringly to oppose the Japanese fa~ists 1 . -

Weekly Briefing Note Southeastern Myanmar 22 - 28 May 2021 (Limited Distribution)

Weekly Briefing Note Southeastern Myanmar 22 - 28 May 2021 (Limited Distribution) This weekly briefing note, covering humanitarian developments in Southeastern Myanmar from 22 to 28 May, is produced by the Kayin Inter-Agency Coordination of the Southeastern Myanmar Working Group. Highlights • The humanitarian situation severely deteriorated throughout Kayah State, especially in Loikaw and Demoso Townships over the week and has resulted in the displacement of more than 70,000 people since 20 May 2021. • Clashes between the Karen National Union (KNU) and Myanmar Military Forces (MAF) continued in Kayin State and Eastern Bago. • Armed conflict, movement restrictions, landmine risks and displacement continue to severely impact communities, particularly in socio-economic terms. Commodity prices have increased, unemployment is high, and local populations are unable to continue their livelihoods activities. • In areas where fighting is more sporadic, Internally Displaced Populations (IDPs) remain in hiding due to the unpredictability of the situation and fear of further attacks, particularly airstrikes. • Displaced populations continue to have limited access to food, shelter, hygiene and sanitation. Humanitarian Situation The security situation continues to be tense in southeastern Myanmar with indiscriminate mortar shelling, deployment of armed forces and explosions in various locations. Intensified clashes were particularly observed in Kayah State, eastern Bago Region and Kayin State during the week. In Kayin State, clashes between the Karen National Union (KNU) and the Myanmar Armed Forces (MAF) were observed in Ma Htaw and Khway Thay villages in Hpapun Township on 21 and 22 May 20211 2 3 and in Wah Lu, Mae Waing, Hpar Loh Doh and Hpar Loh Pho areas, as well as on the road between Hpapun and Ka Taing Ti in Hpapun Township on 24 and 25 May 2021.4 5 Two landmine incidents were reported from Hpapun Township, near War Tho Kho village, on the road between Kamamaung and Hpapun on 24 and 25 May 2021. -

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

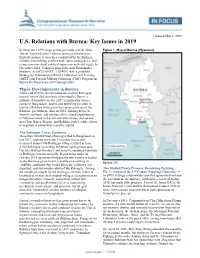

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

MISY: Mandalay Campus 2018/2019 Calendar M O Tu W E Th Fr S a Su

MISY: Mandalay Campus 2018/2019 Calendar M W S o Tu e Th Fr a Su Important Dates th th 1 2 3 4 5 10 Aug – 17 Staff induction th 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 25 Aug – School Opening Day Celebration 9.00 am to 12 noon August 27th Aug – Students First Day 2018 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 st (5 days) 31 Aug – Meet the Parents 3.45 pm to 5.30 pm 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 September 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 4th Sep – Fire Drill @ 9.50 am 2018 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 th st (20 days) 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 17 –21 Anti-Bullying Week 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 st October 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 31 October – Teacher Appreciation Day 2018 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 15th – 19th International Week 22nd- 26th Mid-term holiday / 23rd Pre-full moon of Thadingyut / 24th Full moon of 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 th (18 days) Thadingyut / 25 Post-full moon of Thadingyut 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 1st Nov – Fire Drill @ 11.50 am November 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2018 12th Parent, Student, Teacher Conferences (Nursery – Year 8) 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 th th 13 -16 Week Without Walls (Years 7- 8) (20 days) 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 21st Pre-full moon of Tasaungmone / 22nd Full moon of Tasaungmone / 26 27 28 29 30 1 2 2nd National Day 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 December th 14 Christmas Shows Written reports released (Nursery – Year 8) / Last Day of 2018 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Term 1 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 17th School Holidays (10 days) 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 25th Christmas Day 31 31st New Year’s Eve th 1 2 3 4 5 6 4 Independence Day/ 6th Karen New Year Day th st January 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 7 Jan – Students and Teachers 1 Day term 2 2019 -

Recognition and Rebel Authority: Elite-Grassroots Relations in Myanmar’S Ethnic Insurgencies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Goldsmiths Research Online Manuscript submission to Contemporary Politics - Original Article Title: Recognition and Rebel Authority: Elite-Grassroots Relations in Myanmar’s Ethnic Insurgencies Author: David Brenner: [email protected] Lecturer in International Relations Department of Politics University of Surrey Guildford, GU2 7XH, United Kingdom Research Associate Global South Unit Department of International Relations The London School of Economics (LSE) Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom Recognition and Rebel Authority: Elite-Grassroots Relations in Myanmar’s Ethnic Insurgencies ABSTRACT: This article contributes to the emerging scholarship on the internal politics of non-state armed groups and rebel governance by asking how rival rebel leaders capture and lose legitimacy within their own movement. It explores this question by drawing on critical social theory and ethnographic field research on Myanmar’s most important ethnic armed groups: the Karen and Kachin insurgencies. The article finds that authority relations between elites and grassroots in these movements are not primarily linked to the distributional outcomes of their insurgent social orders, as a contractualist understanding of rebel governance would suggest. It is argued that the authority of rebel leaders in both analysed movements rather depends on whether they address their grassroots’ claim to due and proper recognition, enabling the latter to derive self-perceived positive social identities through affiliation to the insurgent collective. This contributes to our understanding of the role that authority relations between differently situated elite and non-elite insurgents play in the factional contestation within rebel movements. -

Competing Forms of Sovereignty in the Karen State of Myanmar

Competing forms of sovereignty in the Karen state of Myanmar ISEAS Working Paper #1 2013 By: Su-Ann Oh1 Email: [email protected] Visiting Research Fellow Regional Economic Studies Programme Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 1 The ISEAS Working Paper Series is published electronically by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each Working Paper. Papers in this series are preliminary in nature and are intended to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The Editorial Committee accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed, which rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. No part of this publication may be produced in any form without permission. Comments are welcomed and may be sent to the author(s) Citations of this electronic publication should be made in the following manner: Author(s), “Title,” ISEAS Working Paper on “…”, No. #, Date, www.iseas.edu.sg Working Paper Editorial Committee Lee Hock Guan (editor) Terence Chong Lee Poh Onn Tin Maung Maung Than Institute of Southeast Asian Studies 30, Heng Mui Keng Terrace Pasir Panjang Singapore 119614 Main Tel: (65) 6778 0955 Main Fax: (65) 6778 1735 Homepage: www.iseas.edu.sg Introduction The Thai-Burmese border, represented by an innocuous line on a map, is more than a marker of geographical space. It articulates the territorial limits of sovereignty2 and represents the ideology behind the doctrine of modern nation-states. Accordingly, every political state must have a definite territorial boundary which corresponds with differences of culture and language. Moreover, territorial sovereignty is absolute, indivisible and mutually exclusive, as set out by the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia. -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Financial Inclusion

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 I LIFT Annual Report 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 II III LIFT Annual Report 2020 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LBVD Livestock Breeding and Veterinary ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Department CBO Community-based Organisation We thank the governments of Australia, Canada, the European Union, LEARN Leveraging Essential Nutrition Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and CSO Civil Society Organisation Actions To Reduce Malnutrition project the United States of America for their kind contributions to improving the livelihoods and food security of rural poor people in Myanmar. Their DAR Department of Agricultural MAM Moderate acute malnutrition support to the Livelihoods and Food Security Fund (LIFT) is gratefully Research acknowledged. M&E Monitoring and evaluation DC Donor Consortium MADB Myanmar Agriculture Department of Agriculture Development Bank DISCLAIMER DoA DoF Department of Fisheries MEAL Monitoring, evaluation, This document is based on information from projects funded by LIFT in accountability and learning 2020 and supported with financial assistance from Australia, Canada, the DRD Department for Rural European Union, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Development MoALI Ministry of Agriculture, Kingdom, and the United States of America. The views expressed herein Livestock and Irrigation should not be taken to reflect the official opinion of the LIFT donors. DSW Department of Social Welfare MoE Ministry of Education Exchange rate: This report converts MMK into -

Dooplaya Situation Update: Kawkareik Township, January to October 2016

Situation Update July 18, 2017 / KHRG # 16-92-S1 Dooplaya Situation Update: Kawkareik Township, January to October 2016 This Situation Update describes events occurring in Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District during the period between January and October 2016, and includes issues regarding army base locations, rape, drugs, villagers’ livelihood, military activities, refugee concerns, development, education, healthcare, land and taxation. • In the last two months, a Burmese man from A--- village raped and killed a 17-year-old girl. The man was arrested and was sent to Tatmadaw military police. The man who committed the rape was also under the influence of drugs. • Drug abuse has been recognised as an ongoing issue in Dooplaya District. Leaders and officials have tried to eliminate drugs, but the drug issue remains. • Refugees from Noh Poe refugee camp in Thailand are concerned that they will face difficulties if they return to Burma/Myanmar because Bo San Aung’s group (DKBA splinter group) started fighting with BGF and Tatmadaw when the refugees were preparing for their return to Burma/Myanmar. The ongoing fighting will cause problems for refugees if they return. Local people residing in Burma/Myanmar are also worried for refugees if they return because fighting could break out at any time. • There are many different armed groups in Dooplaya District who collect taxes. A local farmer reported that he had to pay a rice tax to many different armed groups, which left him with little money after. Situation Update | Kawkareik Township, Dooplaya District (January to October 2016) The following Situation Update was received by KHRG in November 2016. -

Myanmar: the Key Link Between

ADBI Working Paper Series Myanmar: The Key Link between South Asia and Southeast Asia Hector Florento and Maria Isabela Corpuz No. 506 December 2014 Asian Development Bank Institute Hector Florento and Maria Isabela Corpuz are consultants at the Office of Regional Economic Integration, Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. In this paper, “$” refers to US dollars. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Florento, H., and M. I. Corpuz. 2014. Myanmar: The Key Link between South Asia and Southeast Asia. ADBI Working Paper 506. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: http://www.adbi.org/working- paper/2014/12/12/6517.myanmar.key.link.south.southeast.asia/ Please contact the authors for information about this paper. -

English 2014

The Border Consortium November 2014 PROTECTION AND SECURITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH EAST BURMA / MYANMAR With Field Assessments by: Committee for Internally Displaced Karen People (CIDKP) Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) Karen Environment and Social Action Network (KESAN) Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG) Karen Offi ce of Relief and Development (KORD) Karen Women Organisation (KWO) Karenni Evergreen (KEG) Karenni Social Welfare and Development Centre (KSWDC) Karenni National Women’s Organization (KNWO) Mon Relief and Development Committee (MRDC) Shan State Development Foundation (SSDF) The Border Consortium (TBC) 12/5 Convent Road, Bangrak, Suite 307, 99-B Myay Nu Street, Sanchaung, Bangkok, Thailand. Yangon, Myanmar. E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.theborderconsortium.org Front cover photos: Farmers charged with tresspassing on their own lands at court, Hpruso, September 2014, KSWDC Training to survey customary lands, Dawei, July 2013, KESAN Tatmadaw soldier and bulldozer for road construction, Dawei, October 2013, CIDKP Printed by Wanida Press CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Context .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................