Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Important Facts About the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - Emref

Important Facts about the 2015 Myanmar General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) 2015 October Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF 1 Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF ENLIGHTENED MYANMAR RESEARCH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT FOUNDATION (EMReF) This report is a product of the Information Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation EMReF is an accredited non-profit research Strategies for Societies in Transition program. (EMReF has been carrying out political-oriented organization dedicated to socioeconomic and This program is supported by United States studies since 2012. In 2013, EMReF published the political studies in order to provide information Agency for International Development Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010- and evidence-based recommendations for (USAID), Microsoft, the Bill & Melinda Gates 2012). Recently, EMReF studied The Record different stakeholders. EMReF has been Foundation, and the Tableau Foundation.The Keeping and Information Sharing System of extending its role in promoting evidence-based program is housed in the University of Pyithu Hluttaw (the People’s Parliament) and policy making, enhancing political awareness Washington's Henry M. Jackson School of shared the report to all stakeholders and the and participation for citizens and CSOs through International Studies and is run in collaboration public. Currently, EMReF has been regularly providing reliable and trustworthy information with the Technology & Social Change Group collecting some important data and information on political parties and elections, parliamentary (TASCHA) in the University of Washington’s on the elections and political parties. performances, and essential development Information School, and two partner policy issues. -

Myanmar: Conflicts and Human Rights Violations Continue to Cause Displacement

5 March 2009 Myanmar: Conflicts and human rights violations continue to cause displacement Displacement as a result of conflict and human rights violations continued in Myanmar in 2008. An estimated 66,000 people from ethnic minority communities in eastern Myanmar were forced to become displaced in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict and human rights abuses. As of October 2008, there were at least 451,000 people reported to be inter- nally displaced in the rural areas of eastern Myanmar. This is however a conservative fig- ure, and there is no information available on figures for internally displaced people (IDPs) in several parts of the country. In 2008, the displacement crisis continued to be most acute in Kayin (Karen) State in the east of the country where an intense offensive by the Myanmar army against ethnic insur- gent groups had been ongoing since late 2005. As of October 2008, there were reportedly over 100,000 IDPs in the state. New displacement was also reported in 2008 in western Myanmar’s Chin State as a result of human rights violations and severe food insecurity. People also continued to be displaced in some parts of the country due to a combination of coercive measures such as forced la- bour and land confiscation that left them with no choice but to migrate, often in the context of state-sponsored development initiatives. IDPs living in the areas of Myanmar still affected by armed conflict between the army and insurgent groups remained the most vulnerable, with their priority needs tending to be re- lated to physical security, food, shelter, health and education. -

A Short Outline of the History of the Communist Party of Burma

A SHORT OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF .· THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF BURMA I Burma was an independent kingdom before annexation by the British imperialist in 1824. In 1885 British imperialist annexed whole of Burma. Since that time, Burmese people have never given up their fight for regaining their independence. Various armed uprisings and other legal forms of strug gle were used by the Burmese people in their fight to regain indep~ndence. In 19~8 the biggest and the broadest anti-British general _strike over-ran the whole country. The workers were on strike, the peasants marched up to Rangoon and all the students deserted their class-room to join the workers and peasants. It was an unprecendented anti-British movement in Burma popularly called in Burmese as "1300th movement". Out of this national and class struggle of the Burmese people and working class emerges the Communist Party of Burma. II The Communist Party of Burma was of!i~ially founded on 15th ~_!l_g~s_b 1939 by _!!nitil)K all MarxisLgr.9J!l!§ in Burma, III From the day of inception, CPB launched an active anti-British struggles up till 1941. It was the core of CPB leadership that led ahti British struggles up till the second world war. IV In 1941, after the Hitlerites treacherously attacked the Soviet Union, CPB changed its tactics and directed its blows against the fascists. v In 1942, Burma was invaded by the Japanese fascists. From that time onwards up till 1945, CPB worked unt~ringly to oppose the Japanese fa~ists 1 . -

Ceasefires Sans Peace Process in Myanmar: the Shan State Army, 1989–2011

Asia Security Initiative Policy Series Working Paper No. 26 September 2013 Ceasefires sans peace process in Myanmar: The Shan State Army, 1989–2011 Samara Yawnghwe Independent researcher Thailand Tin Maung Maung Than Senior Research Fellow Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) Singapore Asia Security Initiative Policy Series: Working Papers i This Policy Series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS). The paper is an outcome of a project on the topic ‘Dynamics for Resolving Internal Conflicts in Southeast Asia’. This topic is part of a broader programme on ‘Bridging Multilevel and Multilateral Approaches to Conflict Prevention and Resolution’ under the Asia Security Initiative (ASI) Research Cluster ‘Responding to Internal Crises and Their Cross Border Effects’ led by the RSIS Centre for NTS Studies. The ASI is supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Visit http://www.asicluster3.com to learn more about the Initiative. More information on the work of the RSIS Centre for NTS Studies can be found at http://www.rsis.edu.sg/nts. Terms of use You are free to publish this material in its entirety or only in part in your newspapers, wire services, internet-based information networks and newsletters and you may use the information in your radio-TV discussions or as a basis for discussion in different fora, provided full credit is given to the author(s) and the Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies, S. -

Hakha Chin Land and Resource Tenure Resource and Land Chin Hakha in Change and Persistence

PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCETENURE PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCE TENURE A STUDY ON LAND DYNAMICS IN THE PERIPHERY OF HAKHA M. Boutry, C. Allaverdian, Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone Of and Lives Land series Myanmar research Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCE TENURE A STUDY ON LAND DYNAMICS IN THE PERIPHERY OF HAKHA M. Boutry, C. Allaverdian, Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series DISCLAIMER Persistence and change in Hakha Chin land and resource tenure: a study on land This document is supported with financial assistance from Australia, Denmark, dynamics in the periphery of Hakha. the European Union, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and Published by GRET, 2018 the Mitsubishi Corporation. The views expressed herein are not to be taken to reflect the official opinion of any of the LIFT donors. Suggestion for citation: Boutry, M., Allaverdian, C. Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone. (2018). Persistence and change in Hakha Chin land and resource tenure: a study on land dynamics in the periphery of Hakha. Of lives of land Myanmar research series. GRET: Yangon. Written by: Maxime Boutry and Celine Allaverdian With the contributions of: Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone and Sung Chin Par Reviewed by: Paul Dewit, Olivier Evrard, Philip Hirsch and Mark Vicol Layout by: studio Turenne Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series The Of Lives and Land series emanates from in-depth socio-anthropological research on land and livelihood dynamics. -

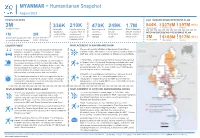

Myanmar – Humanitarian Snapshot (August 2021)

MYANMAR – Humanitarian Snapshot August 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED 2021 HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE PLAN 3M 336K 210K 470K 249K 1.7M 944K $276M $97M (35%) People targeted Requirements Received People in need Internally People internally Non-displaced Returnees and Other vulnerable displaced displaced due to stateless locally people, mostly in INTERIM EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN 1M 2M people at the clashes and persons in integrated urban and peri- start of 2021 Rakhine people urban areas people previously identified people identified insecurity since 2M $109M $17M (15%) February 2021 in conflict-affected areas since 1 February People targeted Requirements Received COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT IN KACHIN AND SHAN A total of 3 million people are targeted for humanitarian The overall security situation in Kachin and Shan states assistance across the country. This includes 1 million remains volatile, with various level of clashes reported between people in need in conflict-affected areas previously MAF and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or among EAOs. identified and a further 2 million people since 1 February. Monsoon flash floods affected around 125,000 people in In Shan State, small-scale population movement was reported the regions and states of Kachin, Kayin, Mandalay, Mon, in Hsipaw, Muse, Kyethi and Mongkaing townships since mid- Rakhine, eastern Shan and Tanintharyi between late July July. In total, 24,950 people have been internally displaced and mid-August, according to local actors. Immediate across Shan State since the start of 2021; over 5,000 people needs of families affected or evacuated have been remain displaced in five townships. addressed by local aid workers and communities. In Kachin, no new displacement has been reported. -

Shan State - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit SHAN STATE - MYANMAR Mohnyin 96°40'E Sinbo 97°30'E 98°20'E 99°10'E 100°0'E 100°50'E 24°45'N 24°45'N Bhutan Dawthponeyan India China Bangladesh Myo Hla Banmauk KACHIN Vietnam Bamaw Laos Airport Bhamo Momauk Indaw Shwegu Lwegel Katha Mansi Thailand Maw Monekoe Hteik Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Konkyan Cambodia 24°0'N Muse 24°0'N Muse Manhlyoe (Manhero) Konkyan Namhkan Tigyaing Namhkan Kutkai Laukkaing Laukkaing Mabein Tarmoenye Takaung Kutkai Chinshwehaw CHINA Mabein Kunlong Namtit Hopang Manton Kunlong Hseni Manton Hseni Hopang Pan Lon 23°15'N 23°15'N Mongmit Namtu Lashio Namtu Mongmit Pangwaun Namhsan Lashio Airport Namhsan Mongmao Mongmao Lashio Thabeikkyin Mogoke Pangwaun Monglon Mongngawt Tangyan Man Kan Kyaukme Namphan Hsipaw Singu Kyaukme Narphan Mongyai Tangyan 22°30'N 22°30'N Mongyai Pangsang Wetlet Nawnghkio Wein Nawnghkio Madaya Hsipaw Pangsang Mongpauk Mandalay CityPyinoolwin Matman Mandalay Anisakan Mongyang Chanmyathazi Ai Airport Kyethi Monghsu Sagaing Kyethi Matman Mongyang Myitnge Tada-U SHAN Monghsu Mongkhet 21°45'N MANDALAY Mongkaing Mongsan 21°45'N Sintgaing Mongkhet Mongla (Hmonesan) Mandalay Mongnawng Intaw international A Kyaukse Mongkaung Mongla Lawksawk Myittha Mongyawng Mongping Tontar Mongyu Kar Li Kunhing Kengtung Laihka Ywangan Lawksawk Kentung Laihka Kunhing Airport Mongyawng Ywangan Mongping Wundwin Kho Lam Pindaya Hopong Pinlon 21°0'N Pindaya 21°0'N Loilen Monghpyak Loilen Nansang Meiktila Taunggyi Monghpyak Thazi Kenglat Nansang Nansang Airport Heho Taunggyi Airport Ayetharyar -

Silencing Dissent

Silencing Dissent SILENCING DISSENT The ongoing imprisonment of Burma’s political activists In the lead up to the 2010 elections Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) P.O Box 93, Mae Sot, Tak Province 63110, Thailand, e.mail: [email protected], web: www.aappb.org Silencing Dissent Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) P.O Box 93, Mae Sot, Tak Province 63110, Thailand, e.mail: [email protected], web: www.aappb.org Silencing Dissent Repression to silence dissent The widespread and unlawful detention of political activists has a significant impact on Burma's political environment in two main ways. Firstly, most of the prominent activists are removed from public or political life. Almost all of the 88 Generation student movement leadership is in prison preventing them from organising against the elections or educating the people on political issues. Lead members of National League for Democracy party, including democracy icon Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, are imprisoned, as are lead ethnic politicians who promote a peaceful tripartite dialogue and national reconciliation, such Gen Hso Ten and U Khun Tun Oo. Secondly, the harsh sentences handed down and the torture and punishments inflicted on political activists threatens the wider population, sending a clear message: refrain from opposition activities or risk the consequences. The consequences are well known. Unlawful arrest and detention and torture are practiced systematically in Burma and occurred throughout 2009 and 2010. These practices pose an ongoing threat to civilians; ensuring populations live in fear, thereby preventing any politically critical activities. This fear stifles dissent, prevents a vibrant civil society and halts any criticism of the regime; key components of a genuine democratic transition. -

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team Seventeen Ethnic Armed Organizations held a conference in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO/KIA on 30 Oct – 2 Nov 2013. At the end of the conference, ethnic leaders established Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT) on Nov 2, 2013. The NCCT will represent to member ethnic armed organizations when negotiating with government peace negotiation team, UPWC. NCCT Leader: • Vice-Chairman : Nai Hong Sar, New Mon State Party • Deputy Leader 1 : General Secretary – Padoh Kwe Htoo Win (Karen National Union) • Deputy Leader 2 : Deputy Commander-in-Chief – Maj. Gen. Gun Maw (KIA) Member • Lt. Col. Kyaw Han, Arakan Army • Central Committee Member Ms. Mra Raza Lin, Arakan Liberation Party • General Secretary Twan Zaw, Arakan National Council • Presidium Dr. Lian Sakhong, Chin National Front • Col. Saw Lont Lon, Democratic Karen Benevolent Army • Secretary-2 Shwe Myo Thant, Karenni National Progressive Party • Gen. Dr. Timothy, Foreign Affairs, KNU/KNLA Peace Council • Col. Hkun Okker, Patron, Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization • Central Committee member Sai Ba Tun, Shan State Progress Party • Secretary-General Ta Aik Nyunt, Wa National Organization NCCT member Organizations: 1. Arakan Liberation Party 2. Arakan National Council 3. Arakan Army 4. Chin National Front 5. Democratic Karen Benevolent Army 6. Karenni National Progressive Party 7. Chairman, Karen National Union 8. KNU/KNLA Peace Council 9. Lahu Democratic Union 10. Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army 11. New Mon State Party 12. Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization 13. Palaung State Liberation Front 14. Shan State Progress Party 15. Wa National Organiztion 16. Kachin Independence Organization Note: Representatives of Restoration Council of Shan State attended the ethnic armed organizations conference held in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO. -

Financial Inclusion

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 I LIFT Annual Report 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 II III LIFT Annual Report 2020 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LBVD Livestock Breeding and Veterinary ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Department CBO Community-based Organisation We thank the governments of Australia, Canada, the European Union, LEARN Leveraging Essential Nutrition Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and CSO Civil Society Organisation Actions To Reduce Malnutrition project the United States of America for their kind contributions to improving the livelihoods and food security of rural poor people in Myanmar. Their DAR Department of Agricultural MAM Moderate acute malnutrition support to the Livelihoods and Food Security Fund (LIFT) is gratefully Research acknowledged. M&E Monitoring and evaluation DC Donor Consortium MADB Myanmar Agriculture Department of Agriculture Development Bank DISCLAIMER DoA DoF Department of Fisheries MEAL Monitoring, evaluation, This document is based on information from projects funded by LIFT in accountability and learning 2020 and supported with financial assistance from Australia, Canada, the DRD Department for Rural European Union, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Development MoALI Ministry of Agriculture, Kingdom, and the United States of America. The views expressed herein Livestock and Irrigation should not be taken to reflect the official opinion of the LIFT donors. DSW Department of Social Welfare MoE Ministry of Education Exchange rate: This report converts MMK into -

ITRI High-Level Assessment on OECD Annex II Risks in Wa Territory In

| High-level assessment on OECD risks in Wa territory | May 2015 ITRI High-level assessment on OECD Annex II risks in Wa territory in Myanmar May 2015 v1.0 | High-level assessment on OECD risks in Wa territory | May 2015 Synergy Global Consulting Ltd United Kingdom office: South Africa office: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)1865 558811 Tel: +27 (0) 11 403 3077 www.synergy-global.net 1a Walton Crescent, Forum II, 4th Floor, Braampark Registered in England and Wales 3755559 Oxford OX1 2JG 33 Hoofd Street Registered in South Africa 2008/017622/07 United Kingdom Braamfontein, 2001, Johannesburg, South Africa Client: ITRI Ltd Report Title: High-level assessment on OECD Annex II risks in Wa territory in Myanmar Version: Version 1.0 Date Issued: 11 May 2015 Prepared by: Quentin Sirven Benjamin Nénot Approved by: Ed O’Keefe Front Cover: Panorama of Tachileik, Shan State, Myanmar. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of ITRI Ltd. The report should be reproduced only in full, with no part taken out of context without prior permission. The authors believe the information provided is accurate and reliable, but it is furnished without warranty of any kind. ITRI gives no condition, warranty or representation, express or implied, as to the conclusions and recommendations contained in the report, and potential users shall be responsible for determining the suitability of the information to their own circumstances. -

Recent Arrests List

ƒ ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 8 of the Export and Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Lin of Special Branch President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s S: 25 of the Natural Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Naing law President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and parliament President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Union Assembly, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 5 (U) T Khun Myat M Joint House and Pyithu Hluttaw, the 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and lower house of the Myanmar President U Win Myint were detained.