Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Outline of the History of the Communist Party of Burma

A SHORT OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF .· THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF BURMA I Burma was an independent kingdom before annexation by the British imperialist in 1824. In 1885 British imperialist annexed whole of Burma. Since that time, Burmese people have never given up their fight for regaining their independence. Various armed uprisings and other legal forms of strug gle were used by the Burmese people in their fight to regain indep~ndence. In 19~8 the biggest and the broadest anti-British general _strike over-ran the whole country. The workers were on strike, the peasants marched up to Rangoon and all the students deserted their class-room to join the workers and peasants. It was an unprecendented anti-British movement in Burma popularly called in Burmese as "1300th movement". Out of this national and class struggle of the Burmese people and working class emerges the Communist Party of Burma. II The Communist Party of Burma was of!i~ially founded on 15th ~_!l_g~s_b 1939 by _!!nitil)K all MarxisLgr.9J!l!§ in Burma, III From the day of inception, CPB launched an active anti-British struggles up till 1941. It was the core of CPB leadership that led ahti British struggles up till the second world war. IV In 1941, after the Hitlerites treacherously attacked the Soviet Union, CPB changed its tactics and directed its blows against the fascists. v In 1942, Burma was invaded by the Japanese fascists. From that time onwards up till 1945, CPB worked unt~ringly to oppose the Japanese fa~ists 1 . -

Reform in Myanmar: One Year On

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°136 Jakarta/Brussels, 11 April 2012 Reform in Myanmar: One Year On mar hosts the South East Asia Games in 2013 and takes I. OVERVIEW over the chairmanship of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2014. One year into the new semi-civilian government, Myanmar has implemented a wide-ranging set of reforms as it em- Reforming the economy is another major issue. While vital barks on a remarkable top-down transition from five dec- and long overdue, there is a risk that making major policy ades of authoritarian rule. In an address to the nation on 1 changes in a context of unreliable data and weak econom- March 2012 marking his first year in office, President Thein ic institutions could create unintended economic shocks. Sein made clear that the goal was to introduce “genuine Given the high levels of impoverishment and vulnerabil- democracy” and that there was still much more to be done. ity, even a relatively minor shock has the potential to have This ambitious agenda includes further democratic reform, a major impact on livelihoods. At a time when expectations healing bitter wounds of the past, rebuilding the economy are running high, and authoritarian controls on the popu- and ensuring the rule of law, as well as respecting ethnic lation have been loosened, there would be a potential for diversity and equality. The changes are real, but the chal- unrest. lenges are complex and numerous. To consolidate and build on what has been achieved and increase the likeli- A third challenge is consolidating peace in ethnic areas. -

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945- )

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945 - ) Major Events in the Life of a Revolutionary Leader All terms appearing in bold are included in the glossary. 1945 On June 19 in Rangoon (now called Yangon), the capital city of Burma (now called Myanmar), Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child and only daughter to Aung San, national hero and leader of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and Daw Khin Kyi, a nurse at Rangoon General Hospital. Aung San Suu Kyi was born into a country with a complex history of colonial domination that began late in the nineteenth century. After a series of wars between Burma and Great Britain, Burma was conquered by the British and annexed to British India in 1885. At first, the Burmese were afforded few rights and given no political autonomy under the British, but by 1923 Burmese nationals were permitted to hold select government offices. In 1935, the British separated Burma from India, giving the country its own constitution, an elected assembly of Burmese nationals, and some measure of self-governance. In 1941, expansionist ambitions led the Japanese to invade Burma, where they defeated the British and overthrew their colonial administration. While at first the Japanese were welcomed as liberators, under their rule more oppressive policies were instituted than under the British, precipitating resistance from Burmese nationalist groups like the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). In 1945, Allied forces drove the Japanese out of Burma and Britain resumed control over the country. 1947 Aung San negotiated the full independence of Burma from British control. -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

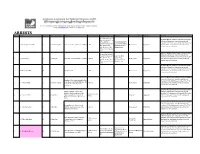

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

Burma Road to Poverty: a Socio-Political Analysis

THE BURMA ROAD TO POVERTY: A SOCIO-POLITICAL ANALYSIS' MYA MAUNG The recent political upheavals and emergence of what I term the "killing field" in the Socialist Republic of Burma under the military dictatorship of Ne Win and his successors received feverish international attention for the brief period of July through September 1988. Most accounts of these events tended to be journalistic and failed to explain their fundamental roots. This article analyzes and explains these phenomena in terms of two basic perspec- tives: a historical analysis of how the states of political and economic devel- opment are closely interrelated, and a socio-political analysis of the impact of the Burmese Way to Socialism 2, adopted and enforced by the military regime, on the structure and functions of Burmese society. Two main hypotheses of this study are: (1) a simple transfer of ownership of resources from the private to the public sector in the name of equity and justice for all by the military autarchy does not and cannot create efficiency or elevate technology to achieve the utopian dream of economic autarky and (2) the Burmese Way to Socialism, as a policy of social change, has not produced significant and fundamental changes in the social structure, culture, and personality of traditional Burmese society to bring about modernization. In fact, the first hypothesis can be confirmed in light of the vicious circle of direct controls-evasions-controls whereby military mismanagement transformed Burma from "the Rice Bowl of Asia," into the present "Rice Hole of Asia." 3 The second hypothesis is more complex and difficult to verify, yet enough evidence suggests that the tradi- tional authoritarian personalities of the military elite and their actions have reinforced traditional barriers to economic growth. -

Fatal Silence ?

FATAL SILENCE ? Freedom of Expression and the Right to Health in Burma ARTICLE 19 July 1996 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was written by Martin Smith, a journalist and specialist writer on Burma and South East Asia. ARTICLE 19 gratefully acknowledges the support of the Open Society Institute for this publication. ARTICLE 19 would also like to acknowledge the considerable information, advice and constructive criticism supplied by very many different individuals and organisations working in the health and humanitarian fields on Burma. Such information was willingly supplied in the hope that it would increase both domestic and international understanding of the serious health problems in Burma. Under current political conditions, however, many aid workers have asked not to be identified. ©ARTICLE 19 ISBN 1 870798139 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be photocopied, recorded or otherwise reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any electronic or technical means without prior permission of the copyright owner and publisher. Note by the editor of this Internet version This version is a conversion to html of a Word document - in the Library at http://www.ibiblio.org/obl/docs/FATAL- SILENCE.doc - derived from a scan of the 1996 hard copy. The footnotes, which in the original were numbered from 1 to __ at the end of each chapter, are now placed at the end of the document, and number 1-207. The footnote references to earlier footnotes have been changed accordingly. In addition, where online versions exist of the documents referred to in the notes and bibliography, the web addresses are given, which was not the case in the original. -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations -

Kengtung LETTERS by Matthew Z

MZW-5 SOUTHEAST ASIA Matthew Wheeler, most recently a RAND Corporation security and terrorism researcher, is studying relations ICWA among and between nations along the Mekong River. Shan State of Mind: Kengtung LETTERS By Matthew Z. Wheeler APRIL 28, 2003 KENGTUNG, Burma – Until very recently, Burmas’s Shan State was, for me, terra Since 1925 the Institute of incognita. For a long time, even after having seen its verdant hills from the Thai Current World Affairs (the Crane- side of the border, my mental map of Southeast Asia represented Shan State as Rogers Foundation) has provided wheat-colored mountains and the odd Buddhist chedi (temple). I suppose this was long-term fellowships to enable a way of representing a place I thought of as remote, obscure, and beautiful. Be- outstanding young professionals yond that, I’d read somewhere that Kengtung, the principal town of eastern Shan to live outside the United States State, had many temples. and write about international areas and issues. An exempt My efforts to conjure a more detailed picture of Shan State inevitably called operating foundation endowed by forth images associated with the Golden Triangle; black-and-white photographs the late Charles R. Crane, the of hillsides covered by poppy plants, ragged militias escorting mules laden with Institute is also supported by opium bundled in burlap, barefoot rebels in formation before a bamboo flagpole. contributions from like-minded These are popular images of the tri-border area where Burma, Laos and Thailand individuals and foundations. meet as haven for “warlord kingpins” ruling over “heroin empires.” As one Shan observer laments, such images, perpetuated by the media and the tourism indus- try, have reduced Shan State’s opium problem to a “dramatic backdrop, an ‘exotic unknowable.’”1 TRUSTEES Bryn Barnard Perhaps my abridged mental image of Shan State persisted by default, since Joseph Battat my efforts to “fill in” the map produced so little clarity. -

The Geopolitics of Change in Burma Bertil Lintner

Asian Studies Centre, St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford Southeast Asia Seminars Wednesday 20th January, 2 p.m. Deakin Room, Founder’s Building, St Antony's College The Geopolitics of Change in Burma Bertil Lintner Independent Journalist and Author The United States and the West did not change their policy of isolating Burma because of their concerns were primarily with the lack of democracy and human rights. It was "the China factor". Burma was becoming a vassal of China, which was seen as a threat to the status quo and regional stability. At the same time, Burma's military was also concerned about China's growing influence and realised that it has to reach out to the West to avoid being absorbed by Chinese political, economic and strategic interests. But in order to "woo the West" they also realised that they had to liberalise the country's rigid political system - but not in a way that would jeopardise their hold on power. Bertil Lintner was born in Sweden in 1953 and left for Asia in 1975. He spent 1975-79 traveling in the Asia-Pacific region (the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, Hong Kong, Japan, Australia and New Zealand). He has been living permanently in Thailand since December 1979, working as a journalist and author. Mr Lintner was a freelance journalist until March 1988, when he was employed by the Far Eastern Economic Review of Hong Kong (for which he began writing on a free-lance basis in 1982) as its Burma correspondent. Later, he also covered a wide range of issues for the Review such as organized crime, ethnic and political insurgencies, and regional security. -

Official Journal of the European Communities 24.5.2000

24.5.2000 EN Official Journal of the European Communities L 122/1 (Acts adopted pursuant to Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION of 26 April 2000 extending and amending Common Position 96/635/CFSP on Burma/Myanmar (2000/346/CFSP) THE COUNCIL OFTHE EUROPEAN UNION, whose names are listed in the Annex and their families. Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in par- ticular Article 15 thereof, By agreement of all Member States, the ban on the issue of an entry visa for the Foreign Minister may Whereas: be waived where it is in the interests of the Euro- (1) Common Position 96/635/CFSP of 28 October 1996 on pean Union; Burma/Myanmar (1) expires on 29 April 2000. (ii) high-level bilateral government (Ministers and offi- cials of political director level and above) visits to (2) There are severe and systematic violations of human Burma/Myanmar will be suspended; rights in Burma, with continuing and intensified repres- (iii) funds held abroad by persons referred to in (i) will sion of civil and political rights, and the Burmese be frozen; authorities have taken no steps towards democracy and national reconciliation. (iv) no equipment which might be used for internal repression or terrorism will be supplied to Burma/ (3) In this connection, the restrictive measures taken under Myanmar.’ Common Position 96/635/CFSP should be extended and strengthened. Article 2 (4) Action by the Community is needed in order to imple- Common Position 96/635/CFSP is hereby extended until 29 ment some of the measures cited below, October 2000.