Kengtung LETTERS by Matthew Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

ITRI High-Level Assessment on OECD Annex II Risks in Wa Territory In

| High-level assessment on OECD risks in Wa territory | May 2015 ITRI High-level assessment on OECD Annex II risks in Wa territory in Myanmar May 2015 v1.0 | High-level assessment on OECD risks in Wa territory | May 2015 Synergy Global Consulting Ltd United Kingdom office: South Africa office: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)1865 558811 Tel: +27 (0) 11 403 3077 www.synergy-global.net 1a Walton Crescent, Forum II, 4th Floor, Braampark Registered in England and Wales 3755559 Oxford OX1 2JG 33 Hoofd Street Registered in South Africa 2008/017622/07 United Kingdom Braamfontein, 2001, Johannesburg, South Africa Client: ITRI Ltd Report Title: High-level assessment on OECD Annex II risks in Wa territory in Myanmar Version: Version 1.0 Date Issued: 11 May 2015 Prepared by: Quentin Sirven Benjamin Nénot Approved by: Ed O’Keefe Front Cover: Panorama of Tachileik, Shan State, Myanmar. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of ITRI Ltd. The report should be reproduced only in full, with no part taken out of context without prior permission. The authors believe the information provided is accurate and reliable, but it is furnished without warranty of any kind. ITRI gives no condition, warranty or representation, express or implied, as to the conclusions and recommendations contained in the report, and potential users shall be responsible for determining the suitability of the information to their own circumstances. -

Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05k6p059 Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 10(2) Author Guyon, Rudy Publication Date 1992 DOI 10.5070/P8102021999 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California COMMENTS VIOLENT REPRESSION IN BURMA: HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE GLOBAL RESPONSE Rudy Guyont TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................ 410 I. SLORC AND THE REPRESSION OF THE DEMOCRACY MOVEMENT ....................... 412 A. Burma: A Troubled History ..................... 412 B. The Pro-Democracy Rebellion and the Coup to Restore Military Control ......................... 414 C. Post Coup Elections and Political Repression ..... 417 D. Legalizing Repression ........................... 419 E. A Country Rife with Poverty, Drugs, and War ... 421 II. HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN BURMA ........... 424 A. Murder and Summary Execution ................ 424 B. Systematic Racial Discrimination ................ 425 C. Forced Dislocations ............................. 426 D. Prolonged Arbitrary Detention .................. 426 E. Torture of Prisoners ............................. 427 F . R ape ............................................ 427 G . Portering ....................................... 428 H. Environmental Devastation ...................... 428 III. VIOLATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW ....... 428 A. International Agreements of Burma .............. 429 1. The U.N. -

The United Nations in Myanmar

The United Nations in Myanmar United Nations Resident & Humanitarian Coordinator LEGEND Ms. Renata Dessallien Produced by : MIMU Date : 4 May 2016 Field Presence (By Office/Staff) Data Source : UN Agencies in Myanmar The United Nations (UN) has been present in Myanmar and assisting vulnerable populations since the country gained its independence in 1948. Head Office The UN Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator (UN RC/HC) is the chief UN official in Myanmar for humanitarian, recovery and Development activities. The UN country-level coordination is managed by the UN Country Team (UNCT) and led by the UN RC/HC. OTHER ENTITIES AND ASSOCIATE COORDINATION FUNDS AND PROGRAMMES SPECIALIZED AGENCIES AGENCIES UN- World UNRC /HC UNO CHA UN IC MIM U UND SS UNIC EF UN DP UNH CR UNO DC UNF PA WF P UNE SCO FA O UNI DO ILO WH O UNA IDS OHC HR UNO PS U N IO M IM F Office of the UN Coordin ation of Informatio n Centre Inform ation Safety and Children 's Fund Develo pment High Com missioner HABI TAT Office on D rugs and Population Fund World Food Educationa l, Scientific Food & Ag ricultural Industrial D evelopment Internation al Labour World Health Joint Prog ramme on High Com missioner Office for Project Interna tional Ban k Intern ational Resident/Humanitarian Humanitarian Affairs Management Unit Security Programme for Refugees Human Settlements Crime Programme & Cultural Organization Organization Organization Organization Organization HIV/AIDS for Human Rights Services WOMEN Organization for Monetary Fund Coordinator Programme Migration Group MANDATES To -

Th E Phaungtaw-U Festival

NOTES TH_E PHAUNGTAW-U FESTIVAL by SAO SAIMONG* Of the numerous Buddhist festivals in Burma, the Phaungtaw-u Pwe (or 'Phaungtaw-u Festival') is among the most famous. I would like to say a few words on its origins and how the Buddhist religion, or 'Buddha Sii.sanii.', came to Burma, particularly this part of Burma, the Shan States. To Burma and Thailand the term 'Buddha Sii.sanii.' can only mean the Theravii.da Sii.sanii. or simply the 'Sii.sanii.'. I Since Independence this part of Burma has been called 'Shan State'. During the time of the Burmese monarchy it was known as Shanpyi ('Shan Country', pronounced 'Shanpye'). When th~ British came the whole unit was called Shan States because Shanpyi was made up of states of various sizes, from more than 10,000 square miles to a dozen square miles. As I am dealing mostly with the past in this short talk I shall be using this term Shan States. History books of Burma written in English and accessible to the outside world tell us that the Sii.sanii. in its purest form was brought to Pagan as the result of the conversion by the Mahii.thera Arahan of King Aniruddha ('Anawrahtii.' in Burmese) who then proceeded to conquer Thaton (Suddhammapura) in AD 1057 and brought in more monks and the Tipitaka, enabling the Sii.sanii. to be spread to the rest of the country. We are not told how Thaton itself obtained the Sii.sanii.. The Mahavamsa and chronicles in Burma and Thailand, however, tell us that the Sii.sanii. -

China Thailand Laos

MYANMAR IDP Sites in Shan State As of 30 June 2021 BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH MYANMAR Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND CHINA List of IDP Sites In nothern Shan No. State Township IDP Site IDPs 1 Hseni Nam Sa Larp 267 2 Hsipaw Man Kaung/Naung Ti Kyar Village 120 3 Bang Yang Hka (Mung Ji Pa) 162 4 Galeng (Palaung) & Kone Khem 525 5 Galeng Zup Awng ward 5 RC 134 6 Hu Hku & Ho Hko 131 SAGAING Man Yin 7 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church) 245 Man Pying Loi Jon 8 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church-2) 155 Man Nar Pu Wan Chin Mu Lin Huong Aik 9 Mai Yu Lay New (Ta'ang) 398 Yi Hku La Shat Lum In 22 Nam Har 10 Kutkai Man Loi 84 Ngar Oe Shwe Kyaung Kone 11 Mine Yu Lay village ( Old) 264 Muse Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan 12 Mung Hawm 170 Nawng Mo Nam Kat Ho Pawt Man Hin 13 Nam Hpak Ka Mare 250 35 ☇ Konkyan 14 Nam Hpak Ka Ta'ang ( Aung Tha Pyay) 164 Chaung Wa 33 Wein Hpai Man Jat Shwe Ku Keng Kun Taw Pang Gum Nam Ngu Muse Man Mei ☇ Man Ton 15 New Pang Ku 688 Long Gam 36 Man Sum 16 Northern Pan Law 224 Thar Pyauk ☇ 34 Namhkan Lu Swe ☇ 26 Kyu Pat 12 KonkyanTar Shan Loi Mun 17 Shan Zup Aung Camp 1,084 25 Man Set Au Myar Ton Bar 18 His Aw (Chyu Fan) 830 Yae Le Man Pwe Len Lai Shauk Lu Chan Laukkaing 27 Hsi Hsar 19 Shwe Sin (Ward 3) 170 24 Tee Ma Hsin Keng Pang Mawng Hsa Ka 20 Mandung - Jinghpaw 147 Pwe Za Meik Nar Hpai Nyo Chan Yin Kyint Htin (Yan Kyin Htin) Manton Man Pu 19 Khaw Taw 21 Mandung - RC 157 Aw Kar Shwe Htu 13 Nar Lel 18 22 Muse Hpai Kawng 803 Ho Maw 14 Pang Sa Lorp Man Tet Baing Bin Nam Hum Namhkan Ho Et Man KyuLaukkaing 23 Mong Wee Shan 307 Tun Yone Kyar Ti Len Man Sat Man Nar Tun Kaw 6 Man Aw Mone Hka 10 KutkaiNam Hu 24 Nam Hkam - Nay Win Ni (Palawng) 402 Mabein Ton Kwar 23 War Sa Keng Hon Gyet Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Nawng Ae 25 Namhkan Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) 338 Si Ping Kaw Yi Man LongLaukkaing Man Kaw Ho Pang Hopong 9 16 Nar Ngu Pang Paw Long Htan (Tart Lon Htan) 26 Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) II 32 Ma Waw 11 Hko Tar Say Kaw Wein Mun 27 Nam Hkam Catholic Church ( St. -

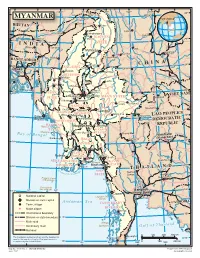

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations -

Adventure Myanmar Overland Tours (Myawaddy – Tachileik/ 12Days – 11Nights)

ADVENTURE MYANMAR OVERLAND TOURS (MYAWADDY – TACHILEIK/ 12DAYS – 11NIGHTS) CUSTOMER REFERENCE Group Name : Mr. Kurt Rasmussen and party Group Size : 6 Pax Tour Code : OSG-20012202 Arrival Date : JAN Departure Date : JAN HIGHLIGHTS Myawaddy – Hpa an – Kyaikhto – Taungoo – Bagan – Popa - Mandalay - Nyaung Shwe – Inle Lake – Namsang – Kengtung – Tachileik Departure BRIEF ITINERARY DAY DATE DESTINATIONS Est. HOURS Est. KILOMETERS Day 1 22nd Jan Myawaddy - Hpa an 03:00 hr 143 Km Day 2 23rd Jan Hpa an - Kyaikhto 02:30 hr 120 Km Day 3 24th Jan Kyaikhto - Taungoo 05:00 hr 220 Km Day 4 25th Jan Taungoo - Bagan 08:00 hr 375 Km Day 5 26th Jan Bagan Sightseeing - - Day 6 27th Jan Bagan - Mt. Popa - Mandalay 04:30 hr 240 Km Day 7 28th Jan Mandalay Sightseeing - - Day 8 29th Jan Mandalay - Nyaung Shwe 06:00 hr 252 Km Day 9 30th Jan Inle Lake Sightseeing - - Day 10 31st Jan Nyaung Shwe - Namsang 04:00 hr 150 Km Day 11 1st Feb Namsang - Kengtung 09:00 hr 340 Km Day 12 2nd Feb Kengtung - Tachileik Departure 03:00 hr 160 Km DETAILED ITINERARY DAY 1: ARRIVAL MYAWADDY DRIVE TO HPA AN Arrival at Myawaddy border, our guide will greet you at the border. Myawaddy border checkpoint will help you with necessary documents as well as represent you the border crossing formalities and procedures at check-point authority’s counters. Then we will drive to Hpa an. Lunch at a local restaurant on the way. Relax and overnight at hotel. Accommodation: DAY 2: DRIVE FROM HPA AN TO KYAIKHTO (B) Breakfast at the hotel. -

Covid-19 Response Situation Report 7 | 30 May 2020

IOM MYANMAR COVID-19 RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 7 | 30 MAY 2020 7,181 migrants returned from Thailand from 22 to 28 May, mainly from Myawaddy-Mae Sot 2,848 migrants returned from China from 22 to 28 May, through Nan Taw and Chin Shwe Haw A COVID-19 risk communication session at Shwe Myawaddy Quarantine Centre in Myawaddy, Kayin State. © IOM 2020 SITUATION OVERVIEW Returns from Thailand began picking up this week, and from Government during the process of applying for employment 22 to 28 May, 7,031 migrants returned through Myawaddy- cards. PRAs are also required to communicate these regulations Mae Sot, and 150 returned through Kawthaung-Ranoung. to respective Thai employers. Should PRAs not follow these These include 1,979 migrants whose return was facilitated instructions, DOL will revoke the license of the PRA concerned. following coordination between the Embassy of Myanmar in Thailand and Thai authorities, with the rest self-arranging their return. Returnees were also tested for COVID-19 upon arrival to Myanmar, with most returnees, upon confirmation of negative test results, being transported to their communities of origin for quarantine. A total of 45,168 migrants returned from Thailand from 22 March to 28 May. The Department of Labour (DOL) issued a letter on 22 May to the Myanmar Overseas Employment Agency Federation (MOEAF) on the restarting of recruitment procedures for Myanmar migrants seeking migration and employment in Thailand. The letter announced that recruitment procedures are on hold until 31 May, and that Thai authorities will accept migrant workers who have health certificates and who undergo Latrines provided by IOM at a quarantine facility in Myawaddy, Kayin State. -

Burma's Foreign Policy with Particular Referenc E to India

X BURMA'S FOREIGN POLICY WITH PARTICULAR REFERENC E TO INDIA A B S T R A C T THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE B y IV:iSS ASHA SHARMA Under the Supervision of Professor Syed Nasir Ali Department of Political bcienc* Dcpariment of Political Science ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, A L I G A R H 1974 ABSTRACT Buitna functions as a link between the two big countries of East, India and China. It is true that inspite of Burma being governed for a long period as a part of Indian Empire, one knows very little about this country, Burma gradually achieved great importance not only for India but also for Southeast Asia and Singapore, Burma is of great importance for the defence system of India and Southeast Asia, It was a great puzzle for the outside world. Its aloofness from its neighbour and Its self imposed isolation was an enigma for its neighbours, Burma road and the use of the port of Rangoon acquired great strategic importance. The closing of this road had a great effect on China, the U.S.A. and the Soviet Union and hence provoked many sided protest. The main feature of Burma is that it is an isolated country both politically and geographically, NAgas >*io lived on the borders, repeatedly created a great trouble for the Indian government. Hence It Is necessary for India that the government of Burma should be neutral and amenable to the Interests of Its neighbours, Oua to the formation of a new state of Pakistan in 1947, great danger to the defence of India was posed by the hostile posture of this new state.