Reform in Myanmar: One Year On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State and Region Parliaments

Collected and Presented by Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) State and Region Parliaments Vol.4 | Issue (96) Thursday, 5th March 2020 Yangon Region Hluttaw Draws Up Draft-Bill to Reduce Waste to Public Funds February 16, 2020 The Yangon Region Hluttaw is drafting a bill to reduce waste to public finance due to a lack of transparency and mismanagement of Yangon Region Government, Daw Sandar Min, the Chairwoman of Yangon Region Finance, Planning and Economic Committee, told Irrawaddy. The draft-bill entitled Yangon Region Funds and Investment Law has been drafted and it is being discussed in the chief justice office and Yangon Region Hluttaw Draft-Bill Committee. After that the Yangon Region Finance, Planning and Economic Committee is to meet with business people to obtain their feedbacks on the bill. The bill is written in order to regulate the expense of Yangon Region Government to reduce waste, to establish good management, to curb corruption in leasing and selling government-own assets, and to oversee that business deals are not given to a particular person or organisation, explained Daw Sandar Min. The bill includes clauses to ensure that government activities carried out with investments from the people must truely provide actions amount to breaching those settlers by Yangon Metropolitan services to benefit the people and regulations, Daw Sandar Min added. Development (YMD) which was government companies established The auditor-general’s report on established with public funds and by public fund must be audited by the 2016-17 and 2017-18 audit of spending the money against financial regional auditor general and the Yangon Region Government described rules and regulations of YMD were activities must be reported to the Yangon Region Government flaunting among the issues mentioned in the hluttaw. -

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945- )

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945 - ) Major Events in the Life of a Revolutionary Leader All terms appearing in bold are included in the glossary. 1945 On June 19 in Rangoon (now called Yangon), the capital city of Burma (now called Myanmar), Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child and only daughter to Aung San, national hero and leader of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and Daw Khin Kyi, a nurse at Rangoon General Hospital. Aung San Suu Kyi was born into a country with a complex history of colonial domination that began late in the nineteenth century. After a series of wars between Burma and Great Britain, Burma was conquered by the British and annexed to British India in 1885. At first, the Burmese were afforded few rights and given no political autonomy under the British, but by 1923 Burmese nationals were permitted to hold select government offices. In 1935, the British separated Burma from India, giving the country its own constitution, an elected assembly of Burmese nationals, and some measure of self-governance. In 1941, expansionist ambitions led the Japanese to invade Burma, where they defeated the British and overthrew their colonial administration. While at first the Japanese were welcomed as liberators, under their rule more oppressive policies were instituted than under the British, precipitating resistance from Burmese nationalist groups like the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). In 1945, Allied forces drove the Japanese out of Burma and Britain resumed control over the country. 1947 Aung San negotiated the full independence of Burma from British control. -

Burma - Conduct of Elections and the Release of Opposition Leader Aung San Suu Kyi

C 99 E/120 EN Official Journal of the European Union 3.4.2012 Thursday 25 November 2010 Burma - conduct of elections and the release of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi P7_TA(2010)0450 European Parliament resolution of 25 November 2010 on Burma – conduct of elections and the release of opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi (2012/C 99 E/23) The European Parliament, — having regard to its previous resolutions on Burma, the most recent adopted on 20 May 2010 ( 1 ), — having regard to Articles 18- 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) of 1948, — having regard to Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) of 1966, — having regard to the EU Presidency Statement of 23 February 2010 calling for all-inclusive dialogue between the authorities and the democratic forces in Burma, — having regard to the statement of the President of the European Parliament Jerzy Buzek of 11 March 2010 on Burma’s new election laws, — having regard to the Chairman’s Statement at the 16th ASEAN Summit held in Hanoi on 9 April 2010, — having regard to the Council Conclusions on Burma adopted at the 3009th Foreign Affairs Council meeting in Luxembourg on 26 April 2010, — having regard to the European Council Conclusions, Declaration on Burma, of 19 June 2010, — having regard to the UN Secretary-General’s report on the situation of human rights in Burma of 28 August 2009, — having regard to the statement made by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in Bangkok on 26 October 2010, — having regard to the Chair’s statement at the -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

Mm-Ami-Conference2015-Chitwin-Passing the Mace

AUSTRALIA MYANMAR INSTITUTE Passing the mace from the Myanmar’s first to the second legislature Chit Win 1/29/2016 When the five year term of the first legislature “Hluttaw” in Myanmar ends in January 2016, it will be remembered as a robust legislature acting as an opposition to the executive. The second legislature of Myanmar is set to be totally different from the first one in every aspect. This paper looks at three key defining features of the first legislature namely non-partisanship, the role of the Speakers and the relationship with the executive and how much of these would be embedded or changed when the mace of the first term of the Hluttaw is passed to the second. Contents 1. Introduction .........................................................................................2 2. Highlights of the first legislature ................................................................2 3. Non-Partisanship ...................................................................................4 4. The role of the Speakers ..........................................................................5 5. Relationship with the executive .................................................................6 6. Conclusion ...........................................................................................8 Annex 1 ...................................................................................................9 Annex 2 .................................................................................................10 !1 Passing the mace from -

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°136 Jakarta/Brussels, 11 April 2012 Reform in Myanmar: One Year On

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°136 Jakarta/Brussels, 11 April 2012 Reform in Myanmar: One Year On mar hosts the South East Asia Games in 2013 and takes I. OVERVIEW over the chairmanship of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2014. One year into the new semi-civilian government, Myanmar has implemented a wide-ranging set of reforms as it em- Reforming the economy is another major issue. While vital barks on a remarkable top-down transition from five dec- and long overdue, there is a risk that making major policy ades of authoritarian rule. In an address to the nation on 1 changes in a context of unreliable data and weak econom- March 2012 marking his first year in office, President Thein ic institutions could create unintended economic shocks. Sein made clear that the goal was to introduce “genuine Given the high levels of impoverishment and vulnerabil- democracy” and that there was still much more to be done. ity, even a relatively minor shock has the potential to have This ambitious agenda includes further democratic reform, a major impact on livelihoods. At a time when expectations healing bitter wounds of the past, rebuilding the economy are running high, and authoritarian controls on the popu- and ensuring the rule of law, as well as respecting ethnic lation have been loosened, there would be a potential for diversity and equality. The changes are real, but the chal- unrest. lenges are complex and numerous. To consolidate and build on what has been achieved and increase the likeli- A third challenge is consolidating peace in ethnic areas. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006

Burma Page 1 of 24 2005 Human Rights Report Released | Daily Press Briefing | Other News... Burma Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006 Since 1962, Burma, with an estimated population of more than 52 million, has been ruled by a succession of highly authoritarian military regimes dominated by the majority Burman ethnic group. The current controlling military regime, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), led by Senior General Than Shwe, is the country's de facto government, with subordinate Peace and Development Councils ruling by decree at the division, state, city, township, ward, and village levels. In 1990 prodemocracy parties won more than 80 percent of the seats in a generally free and fair parliamentary election, but the junta refused to recognize the results. Twice during the year, the SPDC convened the National Convention (NC) as part of its purported "Seven-Step Road Map to Democracy." The NC, designed to produce a new constitution, excluded the largest opposition parties and did not allow free debate. The military government totally controlled the country's armed forces, excluding a few active insurgent groups. The government's human rights record worsened during the year, and the government continued to commit numerous serious abuses. The following human rights abuses were reported: abridgement of the right to change the government extrajudicial killings, including custodial deaths disappearances rape, torture, and beatings of -

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT January 2020

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT January 2020 Contract Number: 72048218C00004 Myanmar Analytical Activity Acknowledgement This report has been written by Kimetrica LLC (www.kimetrica.com) and Mekong Economics (www.mekongeconomics.com) as part of the Myanmar Analytical Activity, and is therefore the exclusive property of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Melissa Earl (Kimetrica) is the author of this report and reachable at [email protected] or at Kimetrica LLC, 80 Garden Center, Suite A-368, Broomfield, CO 80020. The author’s views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID.GOV DECEMBER 2019 MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT | 1 JANUARY 2020 AT A GLANCE Myanmar’s ICOE Finds Insufficient Evidence of Genocide. The ICOE admits there is evidence that Tatmadaw soldiers committed individual war crimes, but rules there is no evidence of a systematic effort to destroy the Rohingya people. (Page 1) The ICJ Rules Myanmar Must Take Measures to Protect the Rohingya From Acts of Genocide. International observers laud the ruling as a major step toward fighting genocide globally, but reactions to the ruling in Myanmar are mixed. (Page 2) Fortify Rights Documents Five Cases of Rohingya IDPs Forced to Accept NVCs. The international community and the Rohingya condemned the cards, saying they are a means to keep the Rohingya from obtaining full citizenship rights by identifying them as “Bengali,” not Rohingya. (Page 3) During the Chinese President’s State Visit to Myanmar, the Two Countries Signed Multiple MoUs. The 33 MoUs that President Xi Jinping cosigned are related to infrastructure, trade, media, and urban development. -

Old and New Competition in Myanmar's Electoral Politics

ISSUE: 2019 No. 104 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore |17 December 2019 Old and New Competition in Myanmar’s Electoral Politics Nyi Nyi Kyaw* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Electoral politics in Myanmar has become more active and competitive since 2018. With polls set for next year, the country has seen mergers among ethnic political parties and the establishment of new national parties. • The ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) party faces more competition than in the run up to the 2015 polls. Then only the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) represented a serious possible electoral rival. • The NLD enjoys the dual advantage of the star power of its chair State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and its status as the incumbent ruling party. • The USDP, ethnic political parties, and new national parties are all potential contenders in the general elections due in late 2020. Among them, only ethnic political parties may pose a challenge to the ruling NLD. * Nyi Nyi Kyaw is Visiting Fellow in the Myanmar Studies Programme of ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. He was previously a postdoctoral fellow at the National University of Singapore and Visiting Fellow at the University of Melbourne. 1 ISSUE: 2019 No. 104 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION The National League for Democracy (NLD) party government under Presidents U Htin Kyaw and U Win Myint1 and State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has been in power since March 2016, after it won Myanmar’s November 2015 polls in a landslide. Four years later, the country eagerly awaits its next general elections, due in late 2020. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

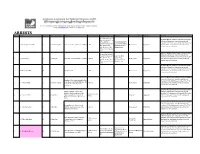

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions.