ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions Around Political Violence in Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin minorityrights.org/minorities/kachin/ June 19, 2015 Profile The Kachin encompass a number of ethnic groups speaking almost a dozen distinct languages belonging to the Tibeto-Burman linguistic family who inhabit the same region in the northern part of Burma on the border with China, mainly in Kachin State. Strictly speaking, these languages are not necessarily closely related, and the term Kachin at times is used to refer specifically to the largest of the groups (the Kachin or Jingpho/Jinghpaw) or to the whole grouping of Tibeto-Burman speaking minorities in the region, which include the Maru, Lisu, Lashu, etc. The exact Kachin population is unknown due to the absence of reliable census data in Burma for more than 60 years. Most estimates suggest there may in the vicinity of 1 million Kachin in the country. The Kachin, as well as the Chin, are one of Burma’s largest Christian minorities: though once again difficult to assess, it is generally thought that between two-thirds and 90 per cent of Kachin are Christians, with others following animist practices or Buddhists. Historical context It is generally thought that the Kachin gradually moved south from their ancestral land on the Tibetan plateau through Yunnan in southern China to arrive in the northern region of what would become Burma sometime during the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, making the Kachin relative newcomers. Their position in this borderland part of South-East Asia meant that the Kachin were often outside of the sphere of influence of Burman kings. Their strength was such by the Third Anglo-Burmese War of 1885 that, while the British were taking Mandalay, the Kachin were getting ready to take advantage of the Burman kingdom’s weakness to attack and take over Mandalay themselves. -

Myanmar: Conflicts and Human Rights Violations Continue to Cause Displacement

5 March 2009 Myanmar: Conflicts and human rights violations continue to cause displacement Displacement as a result of conflict and human rights violations continued in Myanmar in 2008. An estimated 66,000 people from ethnic minority communities in eastern Myanmar were forced to become displaced in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict and human rights abuses. As of October 2008, there were at least 451,000 people reported to be inter- nally displaced in the rural areas of eastern Myanmar. This is however a conservative fig- ure, and there is no information available on figures for internally displaced people (IDPs) in several parts of the country. In 2008, the displacement crisis continued to be most acute in Kayin (Karen) State in the east of the country where an intense offensive by the Myanmar army against ethnic insur- gent groups had been ongoing since late 2005. As of October 2008, there were reportedly over 100,000 IDPs in the state. New displacement was also reported in 2008 in western Myanmar’s Chin State as a result of human rights violations and severe food insecurity. People also continued to be displaced in some parts of the country due to a combination of coercive measures such as forced la- bour and land confiscation that left them with no choice but to migrate, often in the context of state-sponsored development initiatives. IDPs living in the areas of Myanmar still affected by armed conflict between the army and insurgent groups remained the most vulnerable, with their priority needs tending to be re- lated to physical security, food, shelter, health and education. -

Ceasefires Sans Peace Process in Myanmar: the Shan State Army, 1989–2011

Asia Security Initiative Policy Series Working Paper No. 26 September 2013 Ceasefires sans peace process in Myanmar: The Shan State Army, 1989–2011 Samara Yawnghwe Independent researcher Thailand Tin Maung Maung Than Senior Research Fellow Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) Singapore Asia Security Initiative Policy Series: Working Papers i This Policy Series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS). The paper is an outcome of a project on the topic ‘Dynamics for Resolving Internal Conflicts in Southeast Asia’. This topic is part of a broader programme on ‘Bridging Multilevel and Multilateral Approaches to Conflict Prevention and Resolution’ under the Asia Security Initiative (ASI) Research Cluster ‘Responding to Internal Crises and Their Cross Border Effects’ led by the RSIS Centre for NTS Studies. The ASI is supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Visit http://www.asicluster3.com to learn more about the Initiative. More information on the work of the RSIS Centre for NTS Studies can be found at http://www.rsis.edu.sg/nts. Terms of use You are free to publish this material in its entirety or only in part in your newspapers, wire services, internet-based information networks and newsletters and you may use the information in your radio-TV discussions or as a basis for discussion in different fora, provided full credit is given to the author(s) and the Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies, S. -

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics acleddata.com/2018/07/21/analysis-of-the-fpncc-northern-alliance-and-myanmar-conflict-dynamics/ Elliott Bynum July 21, 2018 With the Myanmar military pressuring all ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), non-signatory EAOs have responded by forming a loose military alliance, called the Northern Alliance, to strengthen their position against the military. As with many alliances in Myanmar’s history, the cohesiveness and long-term viability of the alliance is uncertain. Increased military operations by the Myanmar military against the groups in this alliance, particularly the increased use of remote violence, has resulted in the alliance groups shifting their tactics both politically and militarily. In 2016, four EAOs formed the Northern Alliance. The driver behind the formation of the Northern Alliance was the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) which has been in conflict with the Myanmar military for several decades. From 1994-2011, the KIA had a bilateral ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar military which held. The conflict reignited in 2011 after the KIA rejected the military’s Border Guard Force (BGF) scheme which would have placed the KIA under the control of the military. At the time, the Myanmar military also had increased its presence in the Kachin region to guard the Chinese construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam which exacerbated tensions, leading eventually to the start of the current war. The KIA has since sought to strengthen its position by providing training and support to the Arakan Army (AA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). -

Myanmar: the Country That ‘Has It All’

Journal of Southeast Asian Human Rights, Vol. 4 Issue. 1 June 2020 pp. 128 – 139 doi: 10.19184/jseahr.v4i1.17922 © University of Jember & Indonesian Consortium for Human Rights Lecturers Myanmar: the country that ‘has it all’ Susan Banki Department of Sociology and Social Policy - the University of Sydney Email: [email protected] Abstract For scholars of Southeast Asia interested in human rights, Myanmar is a country that ‘has it all.’ I use this tongue-in-cheek expression to suggest the myriad ways that the country remains mired in structural challenges that inform its current human rights problems. In this paper, I point out the country’s most glaring structural challenges and link these to its most pressing human rights problems. A brief section about Myanmar in the context of COVID-19 offers the same conclusion as the rest of the article: while there is variance in the actors targeted and the degree of suppression, the underlying patterns of oppression remain unchanged over time. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Nyi Nyi Kyaw for reviewing a draft of this paper and offering helpful comments. I. INTRODUCTION From its independence to the present day, one can look to Myanmar to observe multiple human rights trajectories, which today play out in myriad violations and responses in nearly all regions of the country. With natural resources of jade and teak, a rich cultural heritage with associated physical sites, and a central, if sandwiched, geopolitical location, one might imagine that the moniker I have given the country, ‘The country that has it all’ is a positive one. -

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

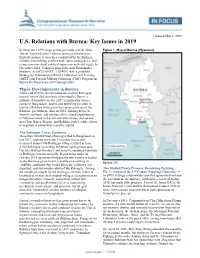

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer

www.ssoar.info Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. https:// doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-2018.1-2 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.de Aktuelle Südostasienforschung Current Research on Southeast Asia Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: The Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Rainer Einzenberger ► Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier capitalism and politics of dispossession in Myanmar: The case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) nickel mine in Chin State. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. Since 2010, Myanmar has experienced unprecedented political and economic changes described in the literature as democratic transition or metamorphosis. The aim of this paper is to analyze the strategy of accumulation by dispossession in the frontier areas as a precondition and persistent element of Myanmar’s transition. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Of the Rome Statute

ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 1/146 RH PT Cour Penale (/\Tl\) _ni _t_e__r an _t_oi _n_a_l_e �i��------------------ ----- International �� �d? Crimi nal Court Original: English No.: ICC-01/19 Date: 4 July 2019 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Olga Herrera Carbuccia, Presiding Judge Judge Robert Fremr Judge Geoffrey Henderson SITUATION IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH / REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR PUBLIC With Confidential EX PARTE Annexes 1, 5, 7 and 8, and Public Annexes 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 and 10 Request for authorisation of an investigation pursuant to article 15 Source: Office of the Prosecutor ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 2/146 RH PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Ms Fatou Bensouda Mr James Stewart Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Counsel Support Section Mr Peter Lewis Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section Mr Philipp Ambach No. ICC-01/19 2/146 4 July 2019 ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 3/146 RH PT CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 5 II. LEVEL OF CONFIDENTIALITY AND REQUESTED PROCEDURE .................... 8 III. PROCEDURAL -

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team Seventeen Ethnic Armed Organizations held a conference in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO/KIA on 30 Oct – 2 Nov 2013. At the end of the conference, ethnic leaders established Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT) on Nov 2, 2013. The NCCT will represent to member ethnic armed organizations when negotiating with government peace negotiation team, UPWC. NCCT Leader: • Vice-Chairman : Nai Hong Sar, New Mon State Party • Deputy Leader 1 : General Secretary – Padoh Kwe Htoo Win (Karen National Union) • Deputy Leader 2 : Deputy Commander-in-Chief – Maj. Gen. Gun Maw (KIA) Member • Lt. Col. Kyaw Han, Arakan Army • Central Committee Member Ms. Mra Raza Lin, Arakan Liberation Party • General Secretary Twan Zaw, Arakan National Council • Presidium Dr. Lian Sakhong, Chin National Front • Col. Saw Lont Lon, Democratic Karen Benevolent Army • Secretary-2 Shwe Myo Thant, Karenni National Progressive Party • Gen. Dr. Timothy, Foreign Affairs, KNU/KNLA Peace Council • Col. Hkun Okker, Patron, Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization • Central Committee member Sai Ba Tun, Shan State Progress Party • Secretary-General Ta Aik Nyunt, Wa National Organization NCCT member Organizations: 1. Arakan Liberation Party 2. Arakan National Council 3. Arakan Army 4. Chin National Front 5. Democratic Karen Benevolent Army 6. Karenni National Progressive Party 7. Chairman, Karen National Union 8. KNU/KNLA Peace Council 9. Lahu Democratic Union 10. Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army 11. New Mon State Party 12. Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization 13. Palaung State Liberation Front 14. Shan State Progress Party 15. Wa National Organiztion 16. Kachin Independence Organization Note: Representatives of Restoration Council of Shan State attended the ethnic armed organizations conference held in Laiza, the headquarters of KIO. -

Myanmar's Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement

Myanmar’s Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement BACKGROUNDER - October 20151 1 Photo: Allyson Neville-Morgan/CC SUMMARY examples over the last 25 years were the 1989 agree- The Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement ment with the United Wa State Army (UWSA), (NCA) seeks to achieve a negotiated the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) in settlement between the government of 1994 (albeit which broke down in 2011), and the Myanmar and non-state ethnic armed New Mon State Party (NMSP) in 1995. Upon organizations (EAOs) that paves the way coming to office as president in August 2011, U for peace-building and national dia- Thein Sein initiated an effort to end fighting on logue. Consisting of seven chapters, the a nation-wide scale and invited a large number of “draft” text of the NCA agreed on March EAOs for peace talks, with negotiations initially 31, 2015, stipulates the terms of cease- seeking to secure a series of bilateral accords. Upon fires, their implementation and monitoring, and concluding many of these, the government agreed the roadmap for political dialogue and peace in February 2013 to multilateral negotiations over ahead. As such, the NCA, if signed by all parties, a single-document national ceasefire agreement would represent the first major step in a longer that encompasses the majority of EAOs. Signifi- nationwide peace process. While the government cantly, this was the first time that the government in particular hopes to conclude the NCA before had agreed to negotiate a multilateral ceasefire.2 national elections take place on November 8, de- mands for amendments in the final text, ongoing 2.