Of the Rome Statute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

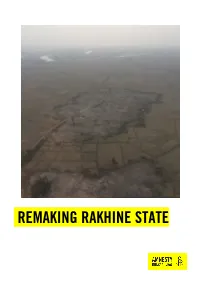

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

July 2020 (23:45 Yangon Time)

Allocation Strategy Paper 2020: FIRST STANDARD ALLOCATION DEADLINE: Monday, 20 July 2020 (23:45 Yangon time) I. ALLOCATION OVERVIEW I.1. Introduction This document lays the strategy to allocating funds from the Myanmar Humanitarian Fund (MHF) First Standard Allocation to scale up the response to the protracted humanitarian crises in Myanmar, in line with the 2020 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP). The allocation responds also to the critical underfunded situation of humanitarian requirements by mid-June 2020. As of 20 June, only 23 per cent of the 2020 HRP requirements, including the revised COVID-19 Addendum, have been met up to now (29 per cent in the case of the mentioned addendum), which is very low in comparison with donor contributions against the HRP in previous years for the same period (50 per cent in 2019 and 40 per cent in 2018). This standard allocation will make available about US$7 million to support coordinated humanitarian assistance and protection, covering displaced people and other vulnerable crisis-affected people in Chin, Rakhine, Kachin and Shan states. The allocation will not include stand-alone interventions related to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), which has been already supported through a Reserve Allocation launched in April 2020, resulting in ten funded projects amounting a total of $3.8 million that are already being implemented. Nevertheless, COVID-19 related actions may be mainstreamed throughout the response to the humanitarian needs. In addition, activities in Kayin State will not be included in this allocation, due to the ongoing projects and level of funding as per HRP requirements. -

WFP Myanmar Country Brief in Numbers

In Numbers 3,385 mt of food assistance distributed US$585,800 cash based transfers made US$26.7 m six months (May-October 2018) net funding requirements, representing 8.6% of total needs WFP Myanmar 295,000 people Country Brief assisted 52% 48% in April 2018 April 2018 Operational Context Operational Updates Myanmar, the second largest country in Southeast Asia, is WFP successfully completed the April food amidst an important political and socio-economic distributions in Rakhine State. In Maungdaw District, transformation. Highly susceptible to natural disasters, WFP assisted 68,500 conflict-affected people, Myanmar ranks 3rd out of 187 countries in the global climate including 2,900 pregnant and lactating women and risk index. An estimated 37.5 percent of its 53 million population live near or below the poverty line. Most in the adolescent girls and 10,000 children under the age of country struggle with physical, social and economic access to five, from Muslim, Buddhist and Hindu communities sufficient, safe and nutritious food with women, girls, elderly, in 123 villages of Buthidaung and Maungdaw persons with disabilities and minorities affected most. Townships. Nearly one in three children under the age of five suffers In Sittwe District, WFP reached 109,500 internally from chronic malnutrition (stunting) while wasting prevails at displaced persons (IDPs) and other conflict affected seven percent nationally. Myanmar is one of the world's 20 populations in townships of Kyaukpyu, Kyauktaw, high tuberculosis burden countries. It is also among 35 Minbya, Mrauk-U, Myebon, Pauktaw, Rathedaung and countries accounting for 90 percent of new HIV infections Sittwe. -

Partnership Against Transnational Crime Through Regional Organized Law Enforcement” (“PATROL”) Project, Led by UNODC

Partnership against Transnational Crime through Regional Organized Law Enforcement (PATROL) Project Number: XAP/U59 Baseline survey and training needs assessment in Myanmar © United Nations Environment Programme 17-21 October 2011 DISCLAIMER: The results from the survey reflect the perception of participants, and they are not the results of specific investigations by UNODC or PATROL partners - Freeland Foundation, TRAFFIC and UNEP. Any error in the interpretation of these results cannot be directly attributed to an official position of any of the organizations involved. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Background and Context – The PATROL Project...................................................... 4 1.2. Objective of the Baseline Survey and TNA................................................................ 4 2. Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. Basic Statistics of the Sample ..................................................................................... 5 2.2. Limitations of the Methodology.................................................................................. 6 3. Major Findings ..................................................................................................................... 7 3.1. Survey Findings.......................................................................................................... -

Central-Rakhine-State-Q4-Report.Pdf

Protection Incident Monitoring System | Protection Sector Myanmar PROTECTION INCIDENT MONITORING SYSTEM: DASHBOARD Reporting Period: October – December 2016 Reporting Area: Central Rakhine State KEY INFORMATION KEY FIGURES In the central parts of Rakhine state, movement restrictions increased for IDPs and Muslims in most locations during the first weeks following the 9 59 reported incidents October attacks against Border Guard Police (BGP) posts in the northern part of Rakhine State. Many humanitarian agencies temporarily reduced 1343 victims their outreach to IDP camps as a precautionary measure due to fear expressed by staff. 77 child victims A total of 59 incidents were reported, affecting 1,343 persons, BREAKDOWN OF VICTIMS BY GENDER: predominantly men. 53% of the incidents were reported as being perpetrated by the government principally the BGP, the Myanmar Police and the Tatmadaw. Female 37 250 people, including 62 children are reported to have been tortured Male 1306 during a military operation in Rathedaung Township. CONTENTS DATA GUIDANCE 1. Protection Incident Monitoring Info-graphic This PIMS dashboard is a quarterly publication of This infographic shows the number of reported incidents and the total number the Protection Sector in Myanmar. This publication aims to provide an overview and trend of affected victims broken down by male, female and children per geographic analysis of the protection concerns prevalent in area. specific regions of Myanmar. This, we hope, will 2. Protection Incident Trend Analysis assist to inform protection and programme This analysis shows trends of protection incidents that occurred in one year. interventions to address protection gaps. This includes (i) Incident trend by violation type and township; (ii) Incident trend by perpetrator and township; (iii) Child victims by violation type; However, PIMS reports do not contain all (iv) Incident trend by township. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020

United Nations A/75/288 General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020 Original: English Seventy-fifth session Item 72 (c) of the provisional agenda* Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives Report on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the General Assembly the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar and on progress in the situation of human rights in Myanmar, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3. * A/75/150. 20-10469 (E) 240820 *2010469* A/75/288 Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Myanmar Summary The independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar issued two reports and four thematic papers. For the present report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights analysed 109 recommendations, grouped thematically on conflict and the protection of civilians; accountability; sexual and gender-based violence; fundamental freedoms; economic, social and cultural rights; institutional and legal reforms; and action by the United Nations system. 2/17 20-10469 A/75/288 I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3, in which the Council requested the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to follow up on the implementation by the Government of Myanmar of the recommendations made by the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar, including those on accountability, and to continue to track progress in relation to human rights, including those of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities, in the country. -

2009 October 26, 2009 Highly Repressive, Authoritarian Military Regimes Have Ruled the Country Since 1962

Burma Page 1 of 12 Burma BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR International Religious Freedom Report 2009 October 26, 2009 Highly repressive, authoritarian military regimes have ruled the country since 1962. In May 2008 the Government announced voters had approved a new draft Constitution in a nationwide referendum. Democracy activists and the international community widely criticized the referendum as seriously flawed. The new Constitution provides for freedom of religion; however, it also grants broad exceptions that allow the regime to restrict those rights at will. Although authorities generally permitted most adherents of registered religious groups to worship as they choose, the Government imposed restrictions on certain religious activities and frequently abused the right to freedom of religion. There was no change in the Government’s limited degree of respect for religious freedom during the reporting period. Religious activities and organizations were subject to restrictions on freedom of expression, association, and assembly. The Government continued to monitor meetings and activities of virtually all organizations, including religious organizations. The Government continued to systematically restrict efforts by Buddhist clergy to promote human rights and political freedom. Many of the Buddhist monks arrested in the violent crackdown that followed pro-democracy demonstrations in September 2007, including prominent activist monk U Gambira, remained in prison serving long sentences. The Government also actively promoted Theravada Buddhism over other religions, particularly among members of ethnic minorities. Christian and Islamic groups continued to struggle to obtain permission to repair existing places of worship or build new ones. The regime continued to closely monitor Muslim activities. Restrictions on worship for other non-Buddhist minority groups also continued. -

Report to the People on the Progress of the Implementation of Recommendations on Rakhine State (January to April 2018)

Report to the People on the Progress of the Implementation of Recommendations on Rakhine State (January to April 2018) Introduction As the Government of Myanmar works towards achieving stability, durable peace and development across the country including Rakhine State, the Committee for Implementation of the Recommendations on Rakhine State was established with an aim to help create a peaceful, fair and prosperous future for the people living in the State. This report provides an update to the people of Myanmar regarding the progress of the implementation by the Committee, for the period of January to April 2018. Economic and Social Development Due compensations are granted for lands acquired from local people for projects necessary for comprehensive development of Rakhine State. Compensations for 6.06 acres of land that was acquired for Kantharyar police station in Gwa Township amounting in 2.7068 million MMK, and for 3.11 acres of acquired for Ahmyintkyun police station in Sittwe Township amounting in 7.775 million MMK are now sanctioned; and authorities are currently processing the payments to the farmers. Compensation for the land acquired for the village tract administrator office of Ahmyintkyun Village Tract in Sittwe Township is included in the FY 2018-19 budget proposal. China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC) and the Government Designated Entity (GOE) as a counterpart from Myanmar are working closely for conducting Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), Social Impact Assessment (SIA) and Geological and Topographical (G.T) Survey for Kyaukpyu Special Economic Zone Project, in order to promote public participation, and to ensure local people can enjoy the benefits from investments and extraction of natural resource in Rakhine State. -

Rendőrségi Tanulmányok

RENDŐRSÉGI TANULMÁNYOK A REND ŐRSÉG TUDOMÁNYOS TANÁCSÁNAK FOLYÓIRATA RITECZ GYÖRGY A terrorizmus hatása a turizmusra NÉMETH GYULA A közúti szállítás biztonságát veszélyeztet ő kihívások az Európát ért terrortámadások tükrében KONCSAG KATALIN Egy kihallgató szemszögéb ől – Hozzátartozók közötti vallomás- megtagadási jog az új Be. tükrében SALLAI JÁNOS In memoriam Dr. Déri Pál nyugállományú rend őr dandártábornok I. évfolyam 2018/4. SZERKESZTI A SZERKESZT ŐBIZOTTSÁG ELNÖK: Dr. Pozsgai Zsolt rend őr vezér őrnagy TAGOK: Dr. habil. Boda József nyugállományú nemzetbiztonsági vezér őrnagy Dr. Boros Gábor rend őr ezredes Dávid Károly rend őr dandártábornok Dr. univ. Dsupin Ottó rend őr dandártábornok Dr. Gárdonyi Gergely PhD rend őr ezredes Dr. habil. Hautzinger Zoltán Dr. Janza Frigyes nyugállományú rend őr vezér őrnagy Prof. Dr. Kerezsi Klára MTA doktora Dr. habil. Kovács Gábor rend őr dandártábornok Dr. Németh József PhD rend őr ezredes Prof. Dr. Sallai János rend őr ezredes Dr. Sipos Gyula rend őr vezér őrnagy FELEL ŐS SZERKESZT Ő: Dr. Gaál Gyula PhD rend őr ezredes MŰSZAKI SZERKESZT Ő: Steib Norbert FELEL ŐS KIADÓ: Dr. Németh József PhD rend őr ezredes, Rend őrség Tudományos Tanácsa elnök KIADÓ Rend őrség Tudományos Tanácsa Cím: 1139 Budapest, Teve u. 4-6. 1903 Bp. Pf.: 314/15. Telefon: +36 1 443-5533, BM: 33-355 Fax: +36 1 443-5784, BM: 33-884 E-mail: [email protected] Webcím: www.bm-tt.hu/rtt/index.html HU ISSN 2630-8002 (online) KÖZLÉSI FELTÉTELEK A szerkeszt őség olyan kéziratokat vár közlésre, amelyek a b űnmegel őzés, a b űnüldözés, a közbiztonság, a közrend, a határrendészet, a vezetés-irányítás és a mindenoldalú biztosítás kérdéseit elemzik, értékelik. -

MYANMAR Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung

I Complex MYANMAR Æ Emergency Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State Imagery analysis: Multiple Dates | Published 18 October 2018 | Version 1.0 CE20130326MMR 92°11'0"E 92°18'0"E 92°25'0"E 92°32'0"E 92°39'0"E 92°46'0"E Thimphu NUMBER OF AFFECTED SETTLEMENTS GROUPED BY LEVEL OF DESTRUCTION ¥¦¬ Level of destruction Buthidaung Maungdaw Rathedaung Total C H I N A Less than 50% destroyed 71 59 4 134 I N D I A More than 50% destroyed 18 62 80 N N Dhaka " Completely destroyed (>90%) 7 156 15 178 " 0 ' 0 ' ¥¦¬ 5 5 2 2 ° ° 1 1 2 Hano¥¦¬i In Tu Lar 2 M YA N M A R ¥¦¬Naypyidaw Vientiane Map location ¥¦¬ T H A I L A N D N N " " 0 ' 0 ' 8 Shee Dar 8 Bangkok 1 1 ° ° 1 1 ¥¦¬ 2 2 Phnom Penh ¥¦¬ Ah Shey Kha Maung Seik Nan Yar Kaing (NaTaLa) Nga/Myin Baw Ku Lar N N " " 0 ' 0 Hpon Thi Laung Boke ' 1 1 Affected settlements in 1 1 ° ° 1 1 2 Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Mu Hti Pa Da Kar Taung 2 Rathedaung Townships of Pa Da Kar Ywar Thit Min Gyi (Ku Lar) Wet Kyein Rakhine State in Myanmar Pe Lun Kha Mway Saung Paing Nyar This map illustrates areas of satellite-detected destroyed or otherwise damaged settlements Goke Pi N N " " 0 ' 0 ' in Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung 4 See inset for close-up view 4 ° ° 1 1 2 Townships in Northern Rakhine State in of destroyed structures 2 Myanmar. -

The Lanzarote Committee: Protecting Children from Sexual 24 Violence in Europe and Beyond

Copyright © 2020 by University of Pécs - Centre for European Research and Education All rights reserved. This journal or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher ex- cept for the use of brief quotations in a journal review. www.ceere.eu/pjiel Table of Contents EDITORIAL: In this issue; I came in here for an argument! The German Federal Cons- 5 titutional Court’s ruling on the PSPP programme and the authority of EU law PETRA PERISIC: Attribution of Conduct in UN Peacekeeping Operations 9 ZSUZSANNA RUTAI: The Lanzarote Committee: protecting children from sexual 24 violence in Europe and beyond PÉTER BUDAI: A new theoretical framework of the law of intergovernmental 43 organizations and its applicability to the European Union PHET SENGPUNYA: Online Dispute Resolution Scheme for E-Commerce: 58 The ASEAN Perspectives ISTVÁN SZIJÁRTÓ: Behind the Efficiency of Joint Investigation Teams 75 ÁGOSTON MOHAY: The Dorobantu case and the applicability of the ECHR in the 85 EU legal order SANDRA FABIJANIĆ GAGRO: The Concept of ‘Junction Area’ – Sui Generis Solution 91 to Reconciling the Integrity of Territorial Sea and ‘Freedoms of Communication’? ISTVÁN TARRÓSY: Helmut Kury and Slawomir Redo (eds.): Refugees and Migrants 103 in Law and Policy. Challenges and Opportunities for Global Civic Education. BENCE KIS KELEMEN: Harold Hongju Koh: The Trump Administration and 108 International law Pécs Journal of International and European Law - 2020/I. Editorial In this issue The editors are pleased to present issue 2020/I of the Pécs Journal of International and European Law, published by the Centre for European Research and Education of the Faculty of Law of the University of Pécs.