Myanmar: the Country That ‘Has It All’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar: Conflicts and Human Rights Violations Continue to Cause Displacement

5 March 2009 Myanmar: Conflicts and human rights violations continue to cause displacement Displacement as a result of conflict and human rights violations continued in Myanmar in 2008. An estimated 66,000 people from ethnic minority communities in eastern Myanmar were forced to become displaced in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict and human rights abuses. As of October 2008, there were at least 451,000 people reported to be inter- nally displaced in the rural areas of eastern Myanmar. This is however a conservative fig- ure, and there is no information available on figures for internally displaced people (IDPs) in several parts of the country. In 2008, the displacement crisis continued to be most acute in Kayin (Karen) State in the east of the country where an intense offensive by the Myanmar army against ethnic insur- gent groups had been ongoing since late 2005. As of October 2008, there were reportedly over 100,000 IDPs in the state. New displacement was also reported in 2008 in western Myanmar’s Chin State as a result of human rights violations and severe food insecurity. People also continued to be displaced in some parts of the country due to a combination of coercive measures such as forced la- bour and land confiscation that left them with no choice but to migrate, often in the context of state-sponsored development initiatives. IDPs living in the areas of Myanmar still affected by armed conflict between the army and insurgent groups remained the most vulnerable, with their priority needs tending to be re- lated to physical security, food, shelter, health and education. -

Arakan Army, AA)

Division de l’information, de la documentation et des recherches – DIDR 9 avril 2021 Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Armée de l’Arakan (Arakan Army, AA) Avertissement Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine, a été élaboré par la DIDR en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière et ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Arakan Army, (AA) Table des matières 1. Principales caractéristiques de l’Arakan Army ................................................................................ 3 1.1. Une organisation liée à la KIA et à l’UWSA ............................................................................. 3 1.2. Relations avec les autres organisations politico-militaires ...................................................... 3 2. Les opérations armées de l’AA ont entraîné des représailles massives ......................................... 4 3. Les interventions de l’AA à des fins logistiques dans les villages ................................................... 5 4. Enlèvements -

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma)

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Watchlist Mission Statement The Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict strives to end violations against children in armed conflicts and to guarantee their rights. As a global network, Watchlist builds partnerships among local, national and international nongovernmental organizations, enhancing mutual capacities and strengths. Working together, we strategically collect and disseminate information on violations against children in conflicts in order to influence key decision-makers to create and implement programs and policies that effectively protect children. Watchlist works within the framework of the provisions adopted in Security Council Resolutions 1261, 1314, 1379, 1460, 1539 and 1612, the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its protocols and other internationally adopted human rights and humanitarian standards. General supervision of Watchlist is provided by a Steering Committee of international nongovernmental organizations known for their work with children and human rights. The views presented in this report do not represent the views of any one organization in the network or the Steering Committee. For further information about Watchlist or specific reports, or to share information about children in a particular conflict situation, please contact: [email protected] www.watchlist.org Photo Credits Cover Photo: UNICEF/NYHQ2006- 1870/Robert Few Please Note: The people represented in the photos in this report are not necessarily themselves victims or survivors of human rights violations or other abuses. No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Notes on Methodology . Information contained in this report is current through January 1, 2009. -

Finding an Endgame in Kachin State the KIO’S Strategies for Finding a Resolution to the Conflict

EBO Background Paper - No .3 | 2018 September 2018 AUTHOR | Paul Keenan Finding an Endgame in Kachin State The KIO’s strategies for finding a resolution to the conflict Since 9 June 2011, Kachin State has seen open (CEFU). The Committee’s purpose was to conflict between the Kachin Independence Army consolidate a political front at a time when the and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military). The Kachin ceasefire groups faced perceived imminent attacks Independence Organisation had signed a ceasefire by the Tatmadaw. However, in November 2010 agreement with the regime in 1994 and since then shortly after the Myanmar elections, the political had lived in relative peace until the ceasefire was grouping was transformed into a military united broken by the Tatmadaw in June 2011. front. At a conference held from the 12-16 February 2011, CEFU declared its dissolution and the The increased territorial infractions by the formation of the United Nationalities Federal Tatmadaw combined with economic exploitation Council (UNFC). The UNFC, which was at that time by China in Kachin territory, especially the comprised of 12 ethnic organisations1, stated that: construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam, left the Kachin Independence Organisation with very The goal of the UNFC is to establish the little alternative but to return to armed resistance future Federal Union (of Myanmar) and to prevent further abuses of its people and their the Federal Union Army is formed for territory’s natural resources. Despite this, however, giving protection to the people of the the political situation since the beginning of country.2 hostilities has changed significantly. -

Child Soldiers in Myanmar: Role of Myanmar Government and Limitations of International Law

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 6 Issue 1 June 2018 Child Soldiers in Myanmar: Role of Myanmar Government and Limitations of International Law Prajakta Gupte Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Prajakta Gupte, Child Soldiers in Myanmar: Role of Myanmar Government and Limitations of International Law, 6 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. (2018). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol6/iss1/15 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2018 VOLUME 6 NO. 1 CHILD SOLDIERS IN MYANMAR: ROLE OF MYANMAR GOVERNMENT AND LIMITATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Prajakta Gupte* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 372 II. BACKGROUND AND HISTORY .................................................... 374 A. Major Political Actors ......................................................... 374 B. Definitions ............................................................................ 376 C. Development of Myanmar’s Society ................................. 377 III. ANALYSIS ...................................................................................... 382 A. Political Stability .................................................................. -

Burma Briefing

Burma JUNE - AUGUST BRIEFING 2018 JUNE-AUGUST BRIEFINGHighlights: 2018 Humanitarian Figures: > Military aggression against the Kachin has escalated since the beginning of June. 237,000 > Peace talks continue amidst ongoing clashes between ethnic people currently live in camps for armies and the Tatmadaw. internally displaced people > Monsoon season has caused thousands to be displaced 106,000 nationwide. internally displaced people in > A damning UN Report has condemned Aung San Suu Kyi’s Kachin and northern Shan states apparent lack of action in regards to the genocide that the due to ongoing conflict Government army is being accused of. Key Developments: 40% of the displaced are still located in > The Burmese military refuses to rescue those displaced in areas beyond Government Kachin, despite nationwide protests. Churches, monasteries and control existing IDP camps are currently housing an additional 7,000 Kachin. 153,000 Affected by flooding and > The third round of 21CPC talks commenced in the context of landslides escalating fighting between the Tatmadaw and various Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs) and the ongoing Rohingya crisis. 863,000 > Floods and landslides have been reported across Burma people in need of aid because of monsoon season, displacing thousands. 5% > A UN Report into the circumstances of the significant movement of the Rohingya population has called for the of 562 humanitarian aid applications for travel investigation of top military commanders in Myanmar, following authorization to government- revelations of brutality and human rights violations on a fact- controlled areas finding Mission. 1 Context Myanmar (Burma) is a highly ethnically diverse country, consisting of 7 states and headed by de facto leader State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi since free elections in 2015. -

CAUGHT in the CROSSFIRE: Witness and Survivor Accounts of Burma Army Attacks and Human Rights Violations in Arakan State

CAUGHT IN THE CROSSFIRE: Witness and Survivor Accounts of Burma Army Attacks and Human Rights Violations in Arakan State WARNING: This report contains graphic photos Caught in the Crossfire At right: Photos of victims of a Burma Army attack in Arakan State on April 13, 2020. For more information on this particular airstrike, please see the photo on page 9. Caught in the Crossfire Free Burma Rangers About this Report This report is the result of 178 interviews conducted, recorded, and translated by Arakan members of the Free Burma Rangers (FBR). The Rangers conducted the interviews during 2019 and submitted the translations and corresponding videos and photos in June 2020. These interviews represent a fraction of the total incidences of Burma Army abuse that is being perpetrated on a grand scale in Arakan State. In March 2020, the Burmese government designated the Arakan Army as a terrorist organization. With this designation, locals fear that the Burmese soldiers will increase the use of torture and detention against civilians in Arakan State with total impunity. Acknowledgements FBR would like to acknowledge and thank the Arakan Rangers for their hard work and dedication in collecting these interviews regarding the ongoing conflict in Arakan State. This report would not be possible without their commitment to getting the news out. We are also grateful to the witnesses who shared their stories and without whose courage in coming forward this report would not have been possible. FBR continues to stand with the Arakan people and others under attack in northern Arakan State as well as Chin State where this particular conflict has spilled into. -

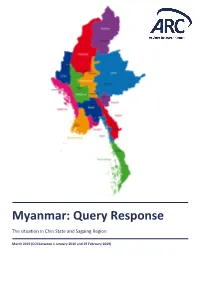

Myanmar: Query Response

Myanmar: Query Response The situation in Chin State and Sagaing Region March 2019 (COI between 1 January 2016 and 19 February 2019) Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. © Asylum Research Centre, 2019 ARC publications are covered by the Creative Commons License allowing for limited use of ARC publications provided the work is properly credited to ARC, it is for non-commercial use and it is not used for derivative works. ARC does not hold the copyright to the content of third party material included in this report. Reproduction or any use of the images/maps/infographics included in this report is prohibited and permission must be sought directly from the copyright holder(s). Please direct any comments to [email protected] Cover photo: © Volina/shutterstock.com 2 Contents Explanatory Note ............................................................................................................................ 7 Sources and databases consulted ................................................................................................. 13 List of acronyms ............................................................................................................................ 17 Map of Myanmar .......................................................................................................................... 18 Map of Chin State ........................................................................................................................ -

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions Around Political Violence in Myanmar

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around Political Violence in Myanmar Coding political violence in Myanmar poses several methodological challenges given the complexity of the many conflicts in the country. In addition to armed conflict between the military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in the borderlands, the military in recent years has used nationlist sentiments to wage a campaign of violence and discrimination against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine state. Further, in the country’s heartland, demonstrations have persisted not just over land and labor issues, but also to demand changes to the military-drafted 2008 constitution. A reference map of the country can be found at the end of this document. Shortly after Myanmar gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1948, several ethnic groups took up arms against the state, demanding equality and the right to self-determination. Divisions between ethnic groups had long been fostered by the colonial practice of ‘divide-and-rule’. This resulted in the center of the country being governed separately from the frontier areas where many ethnic minorities reside. Despite the signing of the Panglong Agreement prior to 1 independence, the failure of the central government to address ethnic concerns led to rebellions by Karen rebels in 1949 and by Kachin rebels in the early 1960s. Other ethnic minorities also took up arms during this period. In March 1962, the military seized power in a coup. It continued with a ‘divide-and-rule’ approach in its dealings with ethnic armed groups, and further adopted a policy of ‘four cuts’, which aimed to eliminate local support for armed groups (Smith, 1991). -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 486 | NOVEMBER 2020 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org The Arakan Army in Myanmar: Deadly Conflict Rises in Rakhine State By David Scott Mathieson Contents Introduction: A Deadly Conflict Rises in Rakhine State .................3 Background and Rise of the Arakan Army ......................4 The Nature of Arakan Army Warfare and Strategy ...................7 Attitudes toward Rohingya and Muslim Minorities ................ 15 Conclusions and Recommendations ...................... 17 Kyaw Han, general secretary of United League of Arakan/Arakan Army, attends a March 2019 meeting with government, military, and ethnic armed organizations. (Photo by Aung Shine Oo/AP) Summary • Myanmar’s most serious conflict Tatmadaw and compounding the narrowing possibilities for political in many decades has emerged human and physical damage. solutions. This conflict will continue in Rakhine State between the • The AA’s sophisticated communi- to escalate absent the AA’s inclu- Myanmar armed forces (Tatmad- cations strategies use social me- sion in the peace process, send- aw) and the Arakan Army (AA), de- dia to swell its recruitment base, ing Rakhine State into a downward manding self-determination for the build civilian support, trade insults spiral that could seriously damage Buddhist Rakhine ethnic minority. It with the Tatmadaw, and reach an the rest of the country. leaves Rohingya refugees with lit- international audience. • With strategic investments to pro- tle chance of a safe return. • Government efforts to marginalize tect in Rakhine’s Kyaukphyu port, • The AA’s guerrilla tactics have and demonize the AA are counter- influence on other armed groups, caused many military and civil- productive with the Rakhine pop- and an interest in the peace pro- ian casualties, evoking a typically ulation, hardening attitudes and cess, China is the only external fierce armed response from the player that can influence the AA. -

Deciphering Myanmar Peace Process a Reference Guide 2016

Deciphering Myanmar’s Peace Process: A Reference Guide 2016 www.bnionline.net www.mmpeacemonitor.org Deciphering Myanmar’s Peace Process: A Reference Guide 2016 Written and Edited by Burma News International Layout/Design by Saw Wanna(Z.H) Previous series: 2013, 2014 and 2015 Latest and 2016 series: January 2017 Printer: Prackhakorn Business Co.,ltd Copyright reserved by Burma News International Published by Burma News International P.O Box 7, Talad Kamtieng PO Chiang Mai, 50304, Thailand E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.mmpeacemonitor.org Twitter: http://twitter.com/mmpeacemonitor Facebook: http:// www.facebook.com/mmpeacemonitor Mapping: http://www.myhistro.com/stories/info.mmpeacemonitor Contents Notes to the reader: . v Executive Summary . vi Acronyms . vii Grand Map of the Peace Process: Introduction . 1 Tracking peace and conlict: An overview . 2 I. Conlict Analysis 2015-2016 . 4 Number of conlicts per EAG 2015 and 2016 . 4 EAO expansions between 2011 - 2016 . 5 The Northern Alliance and continuing armed struggle . 6 Major military incidents per group . 8 Minor Tensions: . 9 Inter-EAG conlicts . 10 Number of clashes or tensions investigated or resolved diplomatically . 10 Armed Groups outside the Peace Process . 12 New Myanmar Army crackdown in Rakhine state . 13 Roots of Rakhine-Rohingya conlict . 15 Spillover of crisis . 16 Repercussions of war . 18 IDPs . 18 Drug production . 20 Communal Conlict . 23 II. The Peace Process Roadmap . 25 Current roadmap . 25 Nationwide Ceaseire Agreement . 29 Step 1: NCA signing . 31 New structure and mechanisms of the NCA peace process . 34 JICM - Nationwide Ceaseire Agreement Joint Implementation Coordination Meeting . -

Armed Conflicts 1946 - 2006 *

Armed Conflicts 1946 - 2006 * Location Incompability Opposition organization Year Intensity level Europe Azerbaijan Govt Husseinov military faction 1993 Minor OPON forces (Otryad Policija Osobogo Naznacenija: Special Police Brigade) 1995 Minor Terr (Nagorno- Karabakh) Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia 1 1992–94 War 2005 Minor* Bosnia and Herzegovina Terr (Serb) Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbian irregulars, Yugoslavia2 1992–93 War 3 1994–95 Minor* * The location column lists the governmental party except in the case of extrasystemic conflicts, which are listed in italics with brackets around the name of the dependent territory, and, with both parties listed in the opposition organization column with the government name in bold. In the case of an interstate conflict, both parties are presented in the location column, with a dash between the two country names. Internationalized internal conflicts have at least one state or multinational coalitions listed with the primary parties to the conflict.All other cases are internal conflicts. Note that the intensity category Intermediate has been removed (see codebook for discussion). However, it is still possible to determine which conflicts have reached a total of at least 1000 battle-related deaths since it started. This is indicated by * in the intensity column. For definitions, see codebook. This document is part of the dataset Armed Conflict 1946–2005, an update of the dataset Armed Conflict 1946–2001 as described in Nils Petter Gleditsch, Peter Wallensteen, Mikael Eriksson, Margareta Sollenberg & Håvard Strand, 2002. ‘Armed Conflict 1946–2001:A New Dataset’, Journal of Peace Research 39(5): 615–637. The latest version of this document can always be found at http://www.prio.no/cwp/armedconflict/ and http://www.ucdp.uu.se/research/UCDP/our_data1.htm 1 Armenia active in 1992–93 and 2005.