The Religious Landscape in Myanmar's Rakhine State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Important Facts About the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - Emref

Important Facts about the 2015 Myanmar General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) 2015 October Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF 1 Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF ENLIGHTENED MYANMAR RESEARCH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT FOUNDATION (EMReF) This report is a product of the Information Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation EMReF is an accredited non-profit research Strategies for Societies in Transition program. (EMReF has been carrying out political-oriented organization dedicated to socioeconomic and This program is supported by United States studies since 2012. In 2013, EMReF published the political studies in order to provide information Agency for International Development Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010- and evidence-based recommendations for (USAID), Microsoft, the Bill & Melinda Gates 2012). Recently, EMReF studied The Record different stakeholders. EMReF has been Foundation, and the Tableau Foundation.The Keeping and Information Sharing System of extending its role in promoting evidence-based program is housed in the University of Pyithu Hluttaw (the People’s Parliament) and policy making, enhancing political awareness Washington's Henry M. Jackson School of shared the report to all stakeholders and the and participation for citizens and CSOs through International Studies and is run in collaboration public. Currently, EMReF has been regularly providing reliable and trustworthy information with the Technology & Social Change Group collecting some important data and information on political parties and elections, parliamentary (TASCHA) in the University of Washington’s on the elections and political parties. performances, and essential development Information School, and two partner policy issues. -

Myanmar: Conflicts and Human Rights Violations Continue to Cause Displacement

5 March 2009 Myanmar: Conflicts and human rights violations continue to cause displacement Displacement as a result of conflict and human rights violations continued in Myanmar in 2008. An estimated 66,000 people from ethnic minority communities in eastern Myanmar were forced to become displaced in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict and human rights abuses. As of October 2008, there were at least 451,000 people reported to be inter- nally displaced in the rural areas of eastern Myanmar. This is however a conservative fig- ure, and there is no information available on figures for internally displaced people (IDPs) in several parts of the country. In 2008, the displacement crisis continued to be most acute in Kayin (Karen) State in the east of the country where an intense offensive by the Myanmar army against ethnic insur- gent groups had been ongoing since late 2005. As of October 2008, there were reportedly over 100,000 IDPs in the state. New displacement was also reported in 2008 in western Myanmar’s Chin State as a result of human rights violations and severe food insecurity. People also continued to be displaced in some parts of the country due to a combination of coercive measures such as forced la- bour and land confiscation that left them with no choice but to migrate, often in the context of state-sponsored development initiatives. IDPs living in the areas of Myanmar still affected by armed conflict between the army and insurgent groups remained the most vulnerable, with their priority needs tending to be re- lated to physical security, food, shelter, health and education. -

Rohingya – the Name and Its Living Archive Jacques Leider

Rohingya – the Name and its Living Archive Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. Rohingya – the Name and its Living Archive. 2018. hal-02325206 HAL Id: hal-02325206 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02325206 Submitted on 25 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Spotlight: The Rakhine Issue Rohingya – the Name and its Living Archive Jacques P. Leider deconstructs the living history of the name “Rohingya.” he intriguingly opposing trends about using, not to do research on the history of the Rohingya and the name Tusing or rejecting the name “Rohingya” illustrate itself. Rohingyas and pro-Rohingya activists were keen to a captivating history of the naming and self-identifying prove that the Union of Burma had already recognised the of Arakan’s Muslim community. Today, “Rohingya” is Rohingya as an ethnic group in the 1950s and 1960s so that globally accepted as the name for most Muslims in North their citizenship rights could not be denied. Academics and Rakhine. But authorities and most people in Myanmar still independent researchers also formed archives containing use the term “Bengalis” in referring to the self-identifying official and non-official documents that allowed a close Rohingyas, linking them to Bangladesh and Burma’s own examination of the chronological record. -

Dr. Jacques P. Leider (Bangkok; Yangon) Muslimische Gemeinschaften Im Buddhistischen Myanmar Die Rohingyafrage. Vom Ethno-Kultur

Gastvorträge zu Religion und Politik in Myanmar / Südostasien Dr. Jacques P. Leider (Bangkok; Yangon) Montag, 25.Juni, 16-18 Uhr. Ort: Hüfferstrasse 27, 3.Obergeschoss, Raum B.3.06 Muslimische Gemeinschaften im buddhistischen Myanmar Der Vortrag bietet einen historischen Überblick über die Bildung muslimischer Gemeinschaften von der Zeit der buddhistischen Königreiche über die Kolonialzeit bis in die Zeit des unabhängigen Birmas (Myanmar). Das Wiedererstarken eines buddhistischen Nationalismus der birmanischen Bevölke-rungsmehrheit ist Hintergund islamophober Gewaltexzesse im Zuge der politischen Öffnung seit 2011. Der historische Rückblick versucht die Aktualität in die gesellschaftlichen Zusammenhänge und die zeitgenössiche Geschichte des Landes einzuordnen. Dienstag, 26.Juni, 10-12 Uhr. Ort: Johannisstr. 8-10, KTh V Die Rohingyafrage. Vom ethno-kulturellen Konflikt zum Vorwurf des staatlichen Genozids Die Rohingyas stellen die grösste muslimische Bevölkerungsgruppe in Myanmar. Die Hälfte der Muslime die die Rohingyaidentität in Anspruch nimmt, lebt aber, teils seit Jahrzehnten, ausserhalb des Landes. Ihre langjährige Unterdrückung, ihre politische Verfolgung und ihre massive Vertreibung haben die humanitären und legalen Aspekte der Rohingyafrage insbesondere seit Mitte 2017 ins Zen-trum des globalen Interesses an Myanmar gerückt. Der Vortrag wird insbesondere die widersprüch-lichen myanmarischen und internationalen Positionen zur Rohingyafrage besprechen. © Sai Lin Aung Htet Dr. Jacques P. Leider ist Historiker und Südostasienforscher der Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient und lebt in Bangkok und Yangon. Der Schwerpunkt seiner wissenschaftlichen Arbeit liegt im Bereich der frühmodernen und kolonialen Geschichte der Königreiche Arakans (Rakhine State) und Birmas (Myanmar). Im Rahmen des ethno-religiösen Konflikts in Rakhine State hat er sich verstärkt mit dem Hintergrund der Identitätsbildung der muslimischen Rohingya im Grenzgebiet zu Bangladesh beschäftigt. -

Myanmar: the Country That ‘Has It All’

Journal of Southeast Asian Human Rights, Vol. 4 Issue. 1 June 2020 pp. 128 – 139 doi: 10.19184/jseahr.v4i1.17922 © University of Jember & Indonesian Consortium for Human Rights Lecturers Myanmar: the country that ‘has it all’ Susan Banki Department of Sociology and Social Policy - the University of Sydney Email: [email protected] Abstract For scholars of Southeast Asia interested in human rights, Myanmar is a country that ‘has it all.’ I use this tongue-in-cheek expression to suggest the myriad ways that the country remains mired in structural challenges that inform its current human rights problems. In this paper, I point out the country’s most glaring structural challenges and link these to its most pressing human rights problems. A brief section about Myanmar in the context of COVID-19 offers the same conclusion as the rest of the article: while there is variance in the actors targeted and the degree of suppression, the underlying patterns of oppression remain unchanged over time. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Nyi Nyi Kyaw for reviewing a draft of this paper and offering helpful comments. I. INTRODUCTION From its independence to the present day, one can look to Myanmar to observe multiple human rights trajectories, which today play out in myriad violations and responses in nearly all regions of the country. With natural resources of jade and teak, a rich cultural heritage with associated physical sites, and a central, if sandwiched, geopolitical location, one might imagine that the moniker I have given the country, ‘The country that has it all’ is a positive one. -

Buddhism and State Power in Myanmar

Buddhism and State Power in Myanmar Asia Report N°290 | 5 September 2017 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Buddhist Nationalism in Myanmar and the Region ........................................................ 3 A. Historical Roots in Myanmar .................................................................................... 3 1. Kingdom and monarchy ....................................................................................... 3 2. British colonial period and independence ........................................................... 4 3. Patriotism and religion ......................................................................................... 5 B. Contemporary Drivers ............................................................................................... 6 1. Emergence of nationalism and violence .............................................................. 6 2. Perceived demographic and religious threats ...................................................... 7 3. Economic and cultural anxieties .......................................................................... 8 4. -

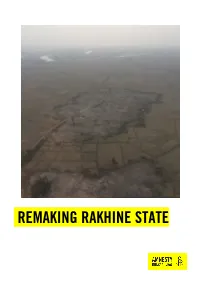

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020

United Nations A/75/288 General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020 Original: English Seventy-fifth session Item 72 (c) of the provisional agenda* Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives Report on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the General Assembly the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar and on progress in the situation of human rights in Myanmar, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3. * A/75/150. 20-10469 (E) 240820 *2010469* A/75/288 Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Myanmar Summary The independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar issued two reports and four thematic papers. For the present report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights analysed 109 recommendations, grouped thematically on conflict and the protection of civilians; accountability; sexual and gender-based violence; fundamental freedoms; economic, social and cultural rights; institutional and legal reforms; and action by the United Nations system. 2/17 20-10469 A/75/288 I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3, in which the Council requested the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to follow up on the implementation by the Government of Myanmar of the recommendations made by the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar, including those on accountability, and to continue to track progress in relation to human rights, including those of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities, in the country. -

Atrocity Crimes Risk Assessment Series

ASIA PACIFIC CENTRE - RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT ATROCITY CRIMES RISK ASSESSMENT SERIES MYANMAR VOLUME 9 - NOVEMBER 2019 Acknowledgements This 2019 updated report was prepared by Ms Elise Park whilst undertaking a volunteer senior in- ternship at the Asia Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect based at the School of Political Science and International Studies at The University of Queensland. We acknowlege the 2017 version author, Ms Ebba Jeppsson (a volunteer senior APR2P intern )and the preliminary background research undertaken in 2016 by volunteer APR2P intern Mr Joshua Appleton-Miles. These internships were supported by the Centre’s staff: Professor Alex Bellamy, Dr Noel Morada, and Ms Arna Chancellor. The Asia Pacific Risk Assessment series is produced as part of the activities of the Asia Pacific Cen- tre for the Responsibility to Protect (AP R2P). Photo acknowledgement: Rohingya refugees make their way down a footpath during a heavy monsoon downpour in Kutupalong refugee settlement, Cox’s Bazar district, Bangladesh. © UNHCR/David Azia.Map Acknowledgement: United Nations Car-tographic Section. Asia Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect School of Political Science and International Studies The University of Queensland St Lucia Brisbane QLD 4072 Australia Email: [email protected] http://www.r2pasiapacific.org/index.html LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AA Arakan Army AHA ASEAN Humanitarian Assistance ALA Arakan Liberation Army ARSA Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations EAO Ethnic Armed -

MYANMAR Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung

I Complex MYANMAR Æ Emergency Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State Imagery analysis: Multiple Dates | Published 18 October 2018 | Version 1.0 CE20130326MMR 92°11'0"E 92°18'0"E 92°25'0"E 92°32'0"E 92°39'0"E 92°46'0"E Thimphu NUMBER OF AFFECTED SETTLEMENTS GROUPED BY LEVEL OF DESTRUCTION ¥¦¬ Level of destruction Buthidaung Maungdaw Rathedaung Total C H I N A Less than 50% destroyed 71 59 4 134 I N D I A More than 50% destroyed 18 62 80 N N Dhaka " Completely destroyed (>90%) 7 156 15 178 " 0 ' 0 ' ¥¦¬ 5 5 2 2 ° ° 1 1 2 Hano¥¦¬i In Tu Lar 2 M YA N M A R ¥¦¬Naypyidaw Vientiane Map location ¥¦¬ T H A I L A N D N N " " 0 ' 0 ' 8 Shee Dar 8 Bangkok 1 1 ° ° 1 1 ¥¦¬ 2 2 Phnom Penh ¥¦¬ Ah Shey Kha Maung Seik Nan Yar Kaing (NaTaLa) Nga/Myin Baw Ku Lar N N " " 0 ' 0 Hpon Thi Laung Boke ' 1 1 Affected settlements in 1 1 ° ° 1 1 2 Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Mu Hti Pa Da Kar Taung 2 Rathedaung Townships of Pa Da Kar Ywar Thit Min Gyi (Ku Lar) Wet Kyein Rakhine State in Myanmar Pe Lun Kha Mway Saung Paing Nyar This map illustrates areas of satellite-detected destroyed or otherwise damaged settlements Goke Pi N N " " 0 ' 0 ' in Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung 4 See inset for close-up view 4 ° ° 1 1 2 Townships in Northern Rakhine State in of destroyed structures 2 Myanmar. -

Of the Rome Statute

ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 1/146 RH PT Cour Penale (/\Tl\) _ni _t_e__r an _t_oi _n_a_l_e �i��------------------ ----- International �� �d? Crimi nal Court Original: English No.: ICC-01/19 Date: 4 July 2019 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Olga Herrera Carbuccia, Presiding Judge Judge Robert Fremr Judge Geoffrey Henderson SITUATION IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH / REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR PUBLIC With Confidential EX PARTE Annexes 1, 5, 7 and 8, and Public Annexes 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 and 10 Request for authorisation of an investigation pursuant to article 15 Source: Office of the Prosecutor ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 2/146 RH PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Ms Fatou Bensouda Mr James Stewart Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Counsel Support Section Mr Peter Lewis Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section Mr Philipp Ambach No. ICC-01/19 2/146 4 July 2019 ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 3/146 RH PT CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 5 II. LEVEL OF CONFIDENTIALITY AND REQUESTED PROCEDURE .................... 8 III. PROCEDURAL