Special Report No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

Important Facts About the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - Emref

Important Facts about the 2015 Myanmar General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) 2015 October Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF 1 Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF ENLIGHTENED MYANMAR RESEARCH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT FOUNDATION (EMReF) This report is a product of the Information Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation EMReF is an accredited non-profit research Strategies for Societies in Transition program. (EMReF has been carrying out political-oriented organization dedicated to socioeconomic and This program is supported by United States studies since 2012. In 2013, EMReF published the political studies in order to provide information Agency for International Development Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010- and evidence-based recommendations for (USAID), Microsoft, the Bill & Melinda Gates 2012). Recently, EMReF studied The Record different stakeholders. EMReF has been Foundation, and the Tableau Foundation.The Keeping and Information Sharing System of extending its role in promoting evidence-based program is housed in the University of Pyithu Hluttaw (the People’s Parliament) and policy making, enhancing political awareness Washington's Henry M. Jackson School of shared the report to all stakeholders and the and participation for citizens and CSOs through International Studies and is run in collaboration public. Currently, EMReF has been regularly providing reliable and trustworthy information with the Technology & Social Change Group collecting some important data and information on political parties and elections, parliamentary (TASCHA) in the University of Washington’s on the elections and political parties. performances, and essential development Information School, and two partner policy issues. -

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin minorityrights.org/minorities/kachin/ June 19, 2015 Profile The Kachin encompass a number of ethnic groups speaking almost a dozen distinct languages belonging to the Tibeto-Burman linguistic family who inhabit the same region in the northern part of Burma on the border with China, mainly in Kachin State. Strictly speaking, these languages are not necessarily closely related, and the term Kachin at times is used to refer specifically to the largest of the groups (the Kachin or Jingpho/Jinghpaw) or to the whole grouping of Tibeto-Burman speaking minorities in the region, which include the Maru, Lisu, Lashu, etc. The exact Kachin population is unknown due to the absence of reliable census data in Burma for more than 60 years. Most estimates suggest there may in the vicinity of 1 million Kachin in the country. The Kachin, as well as the Chin, are one of Burma’s largest Christian minorities: though once again difficult to assess, it is generally thought that between two-thirds and 90 per cent of Kachin are Christians, with others following animist practices or Buddhists. Historical context It is generally thought that the Kachin gradually moved south from their ancestral land on the Tibetan plateau through Yunnan in southern China to arrive in the northern region of what would become Burma sometime during the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, making the Kachin relative newcomers. Their position in this borderland part of South-East Asia meant that the Kachin were often outside of the sphere of influence of Burman kings. Their strength was such by the Third Anglo-Burmese War of 1885 that, while the British were taking Mandalay, the Kachin were getting ready to take advantage of the Burman kingdom’s weakness to attack and take over Mandalay themselves. -

Myanmar: Conflicts and Human Rights Violations Continue to Cause Displacement

5 March 2009 Myanmar: Conflicts and human rights violations continue to cause displacement Displacement as a result of conflict and human rights violations continued in Myanmar in 2008. An estimated 66,000 people from ethnic minority communities in eastern Myanmar were forced to become displaced in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict and human rights abuses. As of October 2008, there were at least 451,000 people reported to be inter- nally displaced in the rural areas of eastern Myanmar. This is however a conservative fig- ure, and there is no information available on figures for internally displaced people (IDPs) in several parts of the country. In 2008, the displacement crisis continued to be most acute in Kayin (Karen) State in the east of the country where an intense offensive by the Myanmar army against ethnic insur- gent groups had been ongoing since late 2005. As of October 2008, there were reportedly over 100,000 IDPs in the state. New displacement was also reported in 2008 in western Myanmar’s Chin State as a result of human rights violations and severe food insecurity. People also continued to be displaced in some parts of the country due to a combination of coercive measures such as forced la- bour and land confiscation that left them with no choice but to migrate, often in the context of state-sponsored development initiatives. IDPs living in the areas of Myanmar still affected by armed conflict between the army and insurgent groups remained the most vulnerable, with their priority needs tending to be re- lated to physical security, food, shelter, health and education. -

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics acleddata.com/2018/07/21/analysis-of-the-fpncc-northern-alliance-and-myanmar-conflict-dynamics/ Elliott Bynum July 21, 2018 With the Myanmar military pressuring all ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), non-signatory EAOs have responded by forming a loose military alliance, called the Northern Alliance, to strengthen their position against the military. As with many alliances in Myanmar’s history, the cohesiveness and long-term viability of the alliance is uncertain. Increased military operations by the Myanmar military against the groups in this alliance, particularly the increased use of remote violence, has resulted in the alliance groups shifting their tactics both politically and militarily. In 2016, four EAOs formed the Northern Alliance. The driver behind the formation of the Northern Alliance was the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) which has been in conflict with the Myanmar military for several decades. From 1994-2011, the KIA had a bilateral ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar military which held. The conflict reignited in 2011 after the KIA rejected the military’s Border Guard Force (BGF) scheme which would have placed the KIA under the control of the military. At the time, the Myanmar military also had increased its presence in the Kachin region to guard the Chinese construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam which exacerbated tensions, leading eventually to the start of the current war. The KIA has since sought to strengthen its position by providing training and support to the Arakan Army (AA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). -

Myanmar: the Country That ‘Has It All’

Journal of Southeast Asian Human Rights, Vol. 4 Issue. 1 June 2020 pp. 128 – 139 doi: 10.19184/jseahr.v4i1.17922 © University of Jember & Indonesian Consortium for Human Rights Lecturers Myanmar: the country that ‘has it all’ Susan Banki Department of Sociology and Social Policy - the University of Sydney Email: [email protected] Abstract For scholars of Southeast Asia interested in human rights, Myanmar is a country that ‘has it all.’ I use this tongue-in-cheek expression to suggest the myriad ways that the country remains mired in structural challenges that inform its current human rights problems. In this paper, I point out the country’s most glaring structural challenges and link these to its most pressing human rights problems. A brief section about Myanmar in the context of COVID-19 offers the same conclusion as the rest of the article: while there is variance in the actors targeted and the degree of suppression, the underlying patterns of oppression remain unchanged over time. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Nyi Nyi Kyaw for reviewing a draft of this paper and offering helpful comments. I. INTRODUCTION From its independence to the present day, one can look to Myanmar to observe multiple human rights trajectories, which today play out in myriad violations and responses in nearly all regions of the country. With natural resources of jade and teak, a rich cultural heritage with associated physical sites, and a central, if sandwiched, geopolitical location, one might imagine that the moniker I have given the country, ‘The country that has it all’ is a positive one. -

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

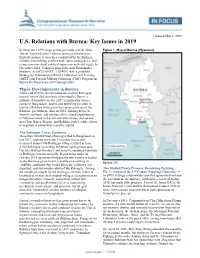

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020

United Nations A/75/288 General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2020 Original: English Seventy-fifth session Item 72 (c) of the provisional agenda* Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives Report on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the General Assembly the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the implementation of the recommendations of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar and on progress in the situation of human rights in Myanmar, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3. * A/75/150. 20-10469 (E) 240820 *2010469* A/75/288 Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Myanmar Summary The independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar issued two reports and four thematic papers. For the present report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights analysed 109 recommendations, grouped thematically on conflict and the protection of civilians; accountability; sexual and gender-based violence; fundamental freedoms; economic, social and cultural rights; institutional and legal reforms; and action by the United Nations system. 2/17 20-10469 A/75/288 I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 42/3, in which the Council requested the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to follow up on the implementation by the Government of Myanmar of the recommendations made by the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar, including those on accountability, and to continue to track progress in relation to human rights, including those of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities, in the country. -

China, India, and Myanmar: Playing Rohingya Roulette?

CHAPTER 4 China, India, and Myanmar: Playing Rohingya Roulette? Hossain Ahmed Taufiq INTRODUCTION It is no secret that both China and India compete for superpower standing in the Asian continent and beyond. Both consider South Asia and Southeast Asia as their power-play pivots. Myanmar, which lies between these two Asian giants, displays the same strategic importance for China and India, geopolitically and geoeconomically. Interestingly, however, both countries can be found on the same page when it comes to the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. As the Myanmar army (the Tatmadaw) crackdown pushed more than 600,000 Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh, Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi’s government was vociferously denounced by the Western and Islamic countries.1 By contrast, China and India strongly sup- ported her beleaguered military-backed government, even as Bangladesh, a country both invest in heavily, particularly on a competitive basis, has sought each to soften Myanmar’s Rohingya crackdown and ease a medi- ated refugee solution. H. A. Taufiq (*) Global Studies & Governance Program, Independent University of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh e-mail: [email protected] © The Author(s) 2019 81 I. Hussain (ed.), South Asia in Global Power Rivalry, Global Political Transitions, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7240-7_4 82 H. A. TAUFIQ China’s and India’s support for Myanmar is nothing new. Since the Myanmar military seized power in September 1988, both the Asian pow- ers endeavoured to expand their influence in the reconfigured Myanmar to protect their national interests, including heavy investments in Myanmar, particularly in the Rakhine state. -

Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project

Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project A preliminary report from the Arakan Rivers Network (ARN) Preliminary Report on the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project November 2009 Copies - 500 Written & Published by Arakan Rivers Network (ARN) P.O Box - 135 Mae Sot Tak - 63110 Thailand Phone: + 66(0)55506618 Emails: [email protected] or [email protected] www.arakanrivers.net Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary …………………………………......................... 1 2. Technical Specifications ………………………………...................... 1 2.1. Development Overview…………………….............................. 1 2.2. Construction Stages…………………….................................... 2 3. Companies and Authorities Involved …………………....................... 3 4. Finance ………………………………………………......................... 3 4.1. Projected Costs........................................................................... 3 4.2. Who will pay? ........................................................................... 4 5. Who will use it? ………………………………………....................... 4 6. Concerns ………………………………………………...................... 4 6.1. Devastation of Local Livelihoods.............................................. 4 6.2. Human rights.............................................................................. 7 6.3. Environmental Damage............................................................. 10 7. India- Burma (Myanmar) Relations...................................................... 19 8. Our Aims and Recommendations to the media................................... -

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations. Morten Bergsmo; Wolfgang Kaleck; Kyaw Yin Hlaing. Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, 40, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, pp.177-227, 2020, Publication Series, 978-82-8348-134-1. hal- 02997366 HAL Id: hal-02997366 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02997366 Submitted on 10 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors) E-Offprint: Jacques P. Leider, “The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations”, in Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors), Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPub- lisher, Brussels, 2020 (ISBNs: 978-82-8348-133-4 (print) and 978-82-8348-134-1 (e- book)). This publication was first published on 9 November 2020. TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site https://www.toaep.org which uses Persistent URLs (PURLs) for all publications it makes available.