Thai-Burmese Warfare During the Sixteenth Century and the Growth of the First Toungoo Empire1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Documented Cases of Linguistic Change

APPENDIX I SOME DOCUMENTED CASES OF LINGUISTIC CHANGE 1. Jinghpaw become Shan The first European to visit Hkamti Long (Putao) was Wilcox in 1828. He recorded of the Shan area that 'the mass of the labouring population is of the Kha-phok tribe whose dialect is closely allied to the Singpho'. Other non-Shan dependents of the Shans were the Kha-lang with villages on the Nam Lang 'whose language more nearly resembles that of the Singpho than that of the Nogmung tribe who are on the Nam Tisang'. The prefix 'Kha-' in Hkamti Shan denotes a serf: 'phok' (hpaw) is a term applied by Maru and Hkamti Shans to Jinghpaw. Kha-phok therefore means 'serf Jinghpaw'. In 1925 Barnard described Hkamti Long as he knew it. He noted that the Shan population included a substantial serf class (lok hka) divided into various 'tribes' which he supposes to have been of Tibetan origin, but he remarks: 'I have not been able to obtain even a small vocabulary of their language as they have been absorbed into the Shans whose language and dress they have completely adopted.' It would appear that Barnard's lok hka must include the descendants of Wilcox's Kha-phok and Kha-lang. The inhabitants of 'the villages on the Nam Lang' now speak Shan; but the Jinghpaw-speaking population on the other side of the Mali Hka-who call them selves Duleng-claim to be related to these 'Shans' of the Nam Lang. Of the Nogmung, Barnard recorded: '(They) are gradually being absorbed by the Shans . -

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

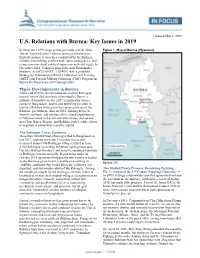

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

5) Bayinnaung in the Hanthawadi Shinbyumya Shin Ayedawbon Chronicle 2.Pmd

Bayinnaung in the Hanthawadi Hsinbyumya Shin Ayedawbon Chronicle by Thaw Kaung King Bayinnaung (AD 1551-1581) is known and respected in Myanmar as a great war- rior king of renown. Bayinnaung refers to himself in the only inscription that he left as “the Conqueror of the Ten Directions”.1 but this epithet is not found in the main Myanmar chronicles or in the Ayedawbon texts. Professor D. G. E. Hall of Rangoon University wrote that “Bayinnaung was a born leader of men. the greatest ever produced by Burma. ”2 There is a separate Ayedawbon historical chronicle devoted specifically to the campaigns and achievements of Bayinnaung entitled Hsinbyumya-shin Ayedawbon.3 Ayedawbon The term Ayedawbon means “a historical account of a royal campaign” 4 It also means a chronicle which records the campaigns and achivements of great kings like Rajadirit, Bayinnaung and Alaungphaya. The Ayedawbon is a Myanmar historical text which records : (1) How great men of prowess like Bayinnaung consolidated their power and became king. (2) How these kings retained their power by military campaigns, diplomacy, alliances and 1. For the full text of The Bell Inscription of King Bayinnaung see Report of the Superintendent, Archaeological Survey, Burma . 1953. Published 1955. p. 17-18. For the English translations by Dr. Than Tun and U Sein Myint see Myanmar Historical Research Journal. no. 8 (Dec. 2001) p. 16-20, 23-27. 2. D. G. E. Hall. Burma. 2nd ed. London : Hutchinson’s University Library, 1956. p.41. 3. The variant titles are Hsinbyushin Ayedawbon and Hanthawadi Ayedawbon. 4. Myanmar - English Dictionary. -

Appendix to Atula Hsayadaw Shin Yasa: a Critical Biography of An

Appendix to Atula Hsayadaw Shin Yasa: a Critical Biography of an Eighteenth‐Century Burmese Monk: Documents related to Atula’s trial in 1784 (version 1.1) Alexey Kirichenko This appendix contains documents that detail the progress of Atula’s trial in 1784 or that were, in my analysis, relevant to it. The original Burmese text of each document is reproduced followed by either a translation or a summary of a document. I also provide comments that explain the contents and the purpose of the document in question. All documents are in chronological order and numbered sequentially. The references in the biography follow these numbers. In reproducing Burmese texts, the original spelling of the manuscripts or the source publications was provisionally retained (with few corrections). In later versions of this appendix I plan to edit the documents in accordance with modern Burmese spelling conventions. The summaries detail the key messages of documents simplifying the style and omitting the quotes from Buddhist texts and some minor points. In future versions the summaries will be replaced by full translations. Document no. 1 Royal order dated the eight day of the waning moon of Nayon 1144 (June 3, 1782) Text: /bkefawmfBuD;jrwfawmfrlvSaom omoem'g,umawmf b0&Sifrifw&m;BuD; trdefUawmf&Sdonf? t&yf&yf q&mawmfoCFmawmftaygifwdkU/ avtoacsFESifh urÇmwodef; yg&rDq,fyg; tjym;oHk;q,fudk jznfhawmfrlí oyÜnKtjzpfodkU a&mufawmfrlaom bk&m;jrwfpGm y&dedAÁmef,lawmfrlonfaemuf ykxkZOf&[ef;wdkU toD;oD; t,l0g' uGJjym;usifhaqmifMuonf/ tZmwowf umvmaomu oD&d"r®maomurifwdkUudk -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

Mon Buddhist Architecture in Pakkret District, Nonthaburi Province, Thailand During Thonburi and Rattanakosin Periods (1767-1932)

MON BUDDHIST ARCHITECTURE IN PAKKRET DISTRICT, NONTHABURI PROVINCE, THAILAND DURING THONBURI AND RATTANAKOSIN PERIODS (1767-1932) Jirada Praebaisri* and Koompong Noobanjong Department of Industrial Education, Faculty of Industrial Education and Technology, King Mongkut's Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, Bangkok 10520, Thailand *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: October 3, 2018; Revised: February 22, 2019; Accepted: April 17, 2019 Abstract This research examines the characteristics of Mon Buddhist architecture during Thonburi and Rattanakosin periods (1767-1932) in Pakkret district. In conjunction with the oral histories acquired from the local residents, the study incorporates inquiries on historical narratives and documents, together with photographic and illustrative materials obtained from physical surveys of thirty religious structures for data collection. The textual investigations indicate that Mon people migrated to the Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya in large number during the 18th century, and established their settlements in and around Pakkret area. Located northwest of the present day Bangkok in Nonthaburi province, Pakkret developed into an important community of the Mon diasporas, possessing a well-organized local administration that contributed to its economic prosperity. Although the Mons was assimilated into the Siamese political structure, they were able to preserve most of their traditions and customs. At the same time, the productions of their cultural artifacts encompassed many Thai elements as well, as evident from Mon Buddhist temples and monasteries in Pakkret. The stylistic analyses of these structures further reveal the following findings. First, their designs were determined by four groups of patrons: Mon laypersons, elite Mons, Thai Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Studies Vol.19(1): 30-58, 2019 Mon Buddhist Architecture in Pakkret District Praebaisri, J. -

Islam in Myanmar – Research Notes Imtiyaz Yusuf

82 Islam in Myanmar – Research Notes Imtiyaz Yusuf Myanmar is a non-secular Buddhist majority country. The Theravada Buddhists and Christians are the two main religious communities groups in Myanmar with the Muslims being the third, enumerated population of Burma tells that, Buddhists make up 89.8 percent of the population, Christians 6.3 percent and Muslims 2.3 percent. The Burmese Muslim community is largely a community of traders and ulama who are economically well but with poor levels of human resources development in the professional fields of education, science, engineering, medicine, technology and business management. Yet, there are several prominent law specialists among them. As a hard and a difficult country, Myanmar was born out of the ashes of the murder of its integrationist freedom fighter leader General Aung San, the father of Aung San Suu Kyi, he was assassinated on 19 July 1947 a few months before the independence of Burma on 4 January 1948. His legacy of seeking integration and the legacy of violence associated with his murder alludes Myanmar until today. In its 69 years of existence, Myanmar is dominated politically by the Bamar Buddhist majority which espouses a Bamar racist interpretation of Buddhism. The Bamar and other 135 distinct ethnic groups are officially grouped into following eight “major national ethnic races” viz., Bamar; Chin; Kachin; Kayin; Kayah; Mon; Rakhine and Shan who are recognized the original natives of the country of Myanmar. Others are classified as outsiders or illegal immigrants as in the case of the Rohingya Muslims. The Muslims in Myanmar are divided into 4 groups: 1) The India Muslims known as Chulias, Kaka and Pathans were brought by the British colonizers to administer the colony. -

THAN, TUN Citation the ROYAL ORDERS of BURMA, AD 1598-1885

Title Introduction Author(s) THAN, TUN THE ROYAL ORDERS OF BURMA, A.D. 1598-1885 (1985), Citation 2: [7]-[18] Issue Date 1985 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/173789 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University INTRODUCTION THE ROYAL ORDERS are arranged in chronological order. A few of the earlier orders that should have been published in Part One, however, were left out for reasons of, what I think, anachronism. Some words, phrases and place names in them do not belong to the date given in them. They are now included in Part Two. Because on second thought, I consider it best to leave the decision to the scholars.: When a date is missing where it should be, I supply it in parenthesis after checking the event in the order against any other record available including the chronicles. When it fails, I would simply give it a date of an order before it or after it as the case may be, because a date ls essential in an order and it was.only through sl~ght that the scribe who had it copied failed to mention it. In the course of collecting these orders, I found quite a number of notes and observations which are not orders but which could be profitably used with the orders. I intend to edit them and put them in an appendix to the last number of these books on the Royal Orders of Burma. A brief survey of political situation ln Burma after the fall of Pagan, as mentioned in some Burmese and Mon inscriptions would be of some interest here. -

Myanmar Exodus from the Shan State

MYANMAR EXODUS FROM THE SHAN STATE “For your own good, don’t destroy others.” Traditional Shan song INTRODUCTION Civilians in the central Shan State are suffering the enormous consequences of internal armed conflict, as fighting between the tatmadaw, or Myanmar army, and the Shan State Army-South (SSA-South) continues. The vast majority of affected people are rice farmers who have been deprived of their lands and their livelihoods as a result of the State Peace and Development Council’s (SPDC, Myanmar’s military government) counter-insurgency tactics. In the last four years over 300,000 civilians have been displaced by the tatmadaw, hundreds have been killed when they attempted to return to their farms, and thousands have been seized by the army to work without pay on roads and other projects. Over 100,000 civilians have fled to neighbouring Thailand, where they work as day labourers, risking arrest for “illegal immigration” by the Thai authorities. In February 2000 Amnesty International interviewed Shan refugees from Laikha, Murngpan, Kunhing, and Namsan townships, central Shan State. All except one stated that they had been forcibly relocated by the tatmadaw. The refugees consistently stated that they had fled from the Shan State because of forced labour and relocations, and because they were afraid of the Myanmar army. They reported instances of the army killing their friends and relatives if they were found trying to forage for food or harvest crops outside of relocation sites. Every refugee interviewed by Amnesty International said that they were forced to build roads, military buildings and carry equipment for the tatmadaw, and many reported that they worked alongside children as young as 10. -

Golden Mrauk-U, The: an Ancient Capital of Rakhine by U Shwe

A GUIDE TO MRAUK - U An Ancient City of Rakhine, Myanmar By Tun Shwe Khine (M.A) First Edition 1992 Historical Sites in Mrauk-U Aerial view of Mrauk-U I <i H Published by U Tun Shwe, Registrar (1) Sittway Degree College, Sittway. Registration No. 450/92 (10) 1992 Nov. 13. Art Adviser and Make-up U Kyaw Hla, Editor, University Translation & Publications Dept., Yangon. Photographs by Ko Tun Shaung, University Translation & Publications Dept., Yangon. Typeset by Shwe Min-Tha-Mee Computer, No. 9 (E), Thalawady Road, 7th mile, Yangon. Printed by U Tha Tun (03333), Nine Nines Press, 25, Razadirat Road, Botahtaung, Yangon. Tha Tun (03333) Cover Registration No. (413/92) (12), printed by U First Edition Jan: 1993, 2000 Copies. Cover - Dukkhanthein Shrine at Sun'set THE GOLDEN CITY OF MRAUK-U The Author Tun Shwe Khine was born in Rambyae, Rakhine State in 1949; graduated from Yangon University in 1972 and obtained master degree in Geography in 1976. He has served as a tutor in Yangon Worker's College; assistant lecturer and registrar (2) in Sittway Degree College. Now he is the Registrar (1) of Sittway Degree College. He has written several research articles and books, and edited some books, magazines and journals. "*,r. Some of his works excluding articles are as follows: (1) Rakhine State Regional Geography (in Myanmar), (2) Ancient Cities ofRakhine (in Myanmar), (3) The History of Rakhine Dynasty (in Myanmar), (4) The Thet Tribe in Northern Rakhine (in Myanmar), (5) Rakhine Buddhist Art in Vesali Period (in Myanmar), (6) Rakhine Folk-Tales (in Myan- mar), (7) Earlier Writers in Rakhine (in Myanmar), (8).4 Study ofRakhine Minthami Aye-gyin (in Myanmar), (9)The History of Rakhine Mahamuni (in Myanmar and English) and (10) Historical Sites in Rakhine (in English). -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

Sports in Pre-Modern and Early Modern Siam: Aggressive and Civilised Masculinities

Sports in Pre-Modern and Early Modern Siam: Aggressive and Civilised Masculinities Charn Panarut A thesis submitted in fulfilment of The requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology and Social Policy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2018 Statement of Authorship This dissertation is the copyrighted work of the author, Charn Panarut, and the University of Sydney. This thesis has not been previously submitted for any degree or other objectives. I certify that this thesis contains no documents previously written or published by anyone except where due reference is referenced in the dissertation itself. i Abstract This thesis is a contribution to two bodies of scholarship: first, the historical understanding of the modernisation process in Siam, and in particular the role of sport in the gradual pacification of violent forms of behaviour; second, one of the central bodies of scholarship used to analyse sport sociologically, the work of Norbert Elias and Eric Dunning on sport and the civilising process. Previous studies of the emergence of a more civilised form of behaviour in modern Siam highlight the imitation of Western civilised conducts in political and sporting contexts, largely overlooking the continued role of violence in this change in Siamese behaviour from the pre- modern to modern periods. This thesis examines the historical evidence which shows that, from around the 1900s, Siamese elites engaged in deliberate projects to civilise prevalent non-elites’ aggressive conducts. This in turn has implications for the Eliasian understanding of sports and civilising process, which emphasises their unplanned development alongside political and economic changes in Europe, at the expense of grasping the deliberate interventions of the Siamese elites.