Children and Armed Conflicts - Key Reports Table (2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

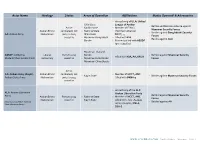

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

CONFLICT BAROMETER 2008 Crises - Wars - Coups D’Etat´ Negotiations - Mediations - Peace Settlements

HEIDELBERG INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT RESEARCH at the Department of Political Science, University of Heidelberg CONFLICT BAROMETER 2008 Crises - Wars - Coups d’Etat´ Negotiations - Mediations - Peace Settlements 17th ANNUAL CONFLICT ANALYSIS HIIK The HEIDELBERG INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT RESEARCH (HIIK) at the Department of Political Science, University of Heidelberg is a registered non-profit association. It is dedicated to research, evaluation and doc- umentation of intra- and interstate political conflicts. The HIIK evolved from the research project ’COSIMO’ (Conflict Simulation Model) led by Prof. Dr. Frank R. Pfetsch (University of Heidelberg) and financed by the German Research Association (DFG) in 1991. Conflict We define conflicts as the clashing of interests (positional differences) over national values of some duration and mag- nitude between at least two parties (organized groups, states, groups of states, organizations) that are determined to pursue their interests and achieve their goals. Conflict items Territory Secession Decolonization Autonomy System/ideology National power Regional predominance International power Resources Others Conflict intensities State of Intensity Level of Name of Definition violence group intensity intensity 1 Latent A positional difference over definable values of national meaning is considered conflict to be a latent conflict if demands are articulated by one of the parties and per- ceived by the other as such. Non-violent Low 2 Manifest A manifest conflict includes the use of measures that are located in the stage conflict preliminary to violent force. This includes for example verbal pressure, threat- ening explicitly with violence, or the imposition of economic sanctions. Medium 3 Crisis A crisis is a tense situation in which at least one of the parties uses violent force in sporadic incidents. -

Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition

United Nations University Centre for Policy Research Crime-Conflict Nexus Series: No 9 April 2017 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition Dr. Vanda Felbab-Brown Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. © 2017 United Nations University. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-92-808-9040-2 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Myanmar case study analyzes the complex interactions between illegal economies -conflict and peace. Particular em- phasis is placed on understanding the effects of illegal economies on Myanmar’s political transitions since the early 1990s, including the current period, up through the first year of the administration of Aung San Suu Kyi. Described is the evolu- tion of illegal economies in drugs, logging, wildlife trafficking, and gems and minerals as well as land grabbing and crony capitalism, showing how they shaped and were shaped by various political transitions. Also examined was the impact of geopolitics and the regional environment, particularly the role of China, both in shaping domestic political developments in Myanmar and dynamics within illicit economies. For decades, Burma has been one of the world’s epicenters of opiate and methamphetamine production. Cultivation of poppy and production of opium have coincided with five decades of complex and fragmented civil war and counterinsur- gency policies. An early 1990s laissez-faire policy of allowing the insurgencies in designated semi-autonomous regions to trade any products – including drugs, timber, jade, and wildlife -- enabled conflict to subside. -

International Actors in Myanmar's Peace Process

ISP-Myanmar research report Working Paper December 30, 2020 International Actors in Myanmar’s Peace Process n Aung Thu Nyein Aung Thu Nyein is EXECUTiVE SUMMARY director of communication and outreach program with the ISP-Myanmar. He is also an The international community has played an important role in supporting editor of "Myanmar Quarterly", an academic journal of the the peace process in Myanmar from the beginning, when the new ISP-Myanmar in Burmese government reached out to the ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) to language and leads a regular initiate – in some cases renew-- ceasefire negotiations in 2011. As the public talk program, Yawmingyi Zayat (Yaw Minister’s Open peace negotiation process has become protracted and even triggered Pavilion). He is a former new armed conflicts in some regions of the country, many international student activist in 1988 actors including donors have come to view Myanmar’s peace process pro-democracy movement and took leadership positions in with cynicism as if it is becoming “a process without peace”. exile democracy movement. He read Masters in Public The surging COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated a sense of peace Administration (M. P. A) at Harvard University in 2002. fatigue, which has sapped attention and resources of the international community from Myanmar. Moreover, the magnitude of the Rohingya crisis and subsequent international interventions coupled with the growing geopolitical rivalry between the United States and China have distracted the attention away from efforts to end a seven-decade long civil war in Myanmar. The National League for Democracy's (NLD) landslide victory in the general elections held in November 2020 means that the party will likely form a government to serve a five-year term. -

PEACE Info (March 16, 2018)

PEACE Info (March 16, 2018) − Myanmar’s Karen Cease-Fire in Jeopardy − New Mon State Party faces birthing pains after signing ceasefire pact − Negotiation, not coercion, offers best hope of peace in Kachin − Press briefings to be held to reduce local concerns over fighting between NMSP and KNU − Tatmadaw Offensive Forces KIA Battalion to Abandon Base in Tanai − Two civilians killed as RCSS-TNLA fighting flares again − Confiscated land returned to farmers − Myanmar returns confiscated land to farmers in eastern state − ၿငိမ္းခ်မ္းေရးျမန္ဆန္သြက္လက္ရန္ အစိုးရႏွင့္တပ္မေတာ္ညႇိႏွိုင္းမွုမ်ားလိုအပ္ဟု ဦးခြန္ဥကၠာသုံးသပ္ − အမ်ဳိးသားအဆင့္ ႏိုင္ငံေရးေဆြးေႏြးပြဲမ်ား မက်င္းပႏုိင္ျခင္းက ၿငိမ္းခ်မ္းေရးလုပ္ငန္းစဥ္ အခက္အခဲျဖစ္ဟု ေကအင္န္ယူ ဒုဥကၠ႒ေျပာ − မြန္ျပည္သစ္ပါတီႏွင့္ KNU ပဋိပကၡထပ္မံမျဖစ္ပြားေရး နည္းလမ္းႏွစ္ခုျဖင့္ ေဆာင္ရြက္မည္ − စစ္ေရးအေျခအေနေၾကာင့္ တႏုိင္းေဒသအေျခစိုက္ ေကအိုင္ေအတပ္ရင္း (၁၄) ေနရာေျပာင္းေရႊ႕ − လမ္းေဖါက္ေနတဲ့တပ္ေတြ ဆုတ္ေပးဖို႔ KNU ေတာင္းဆို − ေကအန္ယူ ထိပ္ပိုင္းေခါင္းေဆာင္ေတြ အေရးေပၚအစည္းအေဝးလုပ္ − အစုိးရတပ္မ်ား ဖာပြန္ခ႐ုိင္တြင္းမွ ျပန္႐ုပ္သိမ္းရန္ ေကအန္ယူ ေတာင္းဆုိ − ဖာပြန္ခရိုင္အတြင္းရိွ အစိုးရတပ္မ်ား ျပန္လည္ဆုတ္ခြာေပးရန္ KNU ေတာင္းဆို − တပ္မေတာ္အေနျဖင့္ နယ္ေျမအတြင္း စစ္ေရးလႈပ္ရွားမႈမ်ားကုိ ရပ္ဆုိင္းရန္ KNU ေျပာ − ဖာပြန္ခရိုင္မွာ တပ္မေတာ္က KNU စစ္ေဆးေရးဂိတ္ကို မီးရိႈ႕ − တပ္မေတာ္ႏွင့္ ေကအန္အယ္လ္ေအ တုိက္ပြဲျဖစ္၊ ေကအန္အယ္လ္ေအတပ္စခန္း ဖ်က္ဆီးခံရ − RCSS ႏွင့္ TNLA တိုက္ပြဲၾကားက ေဒသခံမ်ား မိုင္းအႏၲရာယ္ေၾကာင့္ ကယ္မထုတ္နိုင္ေသး − တိုက္ပြဲအတြင္းပိတ္မိေနေသာ အရပ္သားမ်ားကို ကယ္ထုတ္ႏိုင္ေရး အရပ္ဘက္အဖြဲ႕မ်ား ႀကိဳးစားမႈ မေအာင္ျမင္ − RCSS ႏွင့္ TNLA -

Ethnic Education and Mother Tongue-Based Teaching in Myanmar

Schooling and Conflict: Ethnic Education and Mother Tongue-based Teaching in Myanmar Ashley South and Marie Lall February 2016 Acknowledgements Our thanks go to the respondents in Mon, Kachin and Karen (Kayin) and Kachin States as well as those we met in Yangon and other parts of Myanmar, Thailand and China. Particular thanks to the Mon National Education Committee and to Mi Sar Dar and Mi Kun Chan Non, to Mi Morchai, and to friends in Myitkyina including Saya- ma Lu Awn and Michael Mun Awng. We would also like to thank Sumlut Gun Maw, all at Mai Ja Yang College,- Nai Hongsa and P’doh Tah Do Moo, and Alan Smith, Matt Desmond, Professor Joe Lo Bianco, and Professor Chayan Vaddhanaphuti. Thanks to Michael Woods and Pharawee Koletschka for copy-editing. About the authors Dr. Ashley South is an independent analyst and consultant. He has a PhD from the Australian National Uni- versity and an MSc from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS, University of London), and is a Re- search Fellow at the Centre for Ethnic Studies and Development at Chiang Mai University. His primary research interests include ethnic politics in Myanmar/Burma and Mindanao (armed conflict and comparative peace processes, politics of language and education, peacebuilding policy and practice), humanitarian protection and forced migration (refugees and internally displaced people). For a list of Dr. South’s publications, see: www. AshleySouth.co.uk. Professor Marie Lall, FRSA is a South Asia expert (India, Pakistan and Burma/Myanmar) specialising in political issues and education. She has over 20 years of experience in the region, conducting extensive fieldwork and has lived both in India and Pakistan. -

A Within-Case Analysis of Burma/Myanmar, 1948-2011 Alexa

Why Do Some Insurgent Groups Agree to Ceasefires While Others Do Not? A Within-Case Analysis of Burma/Myanmar, 1948-2011 Alexander Dukalskis University College Dublin [email protected] Final version published in Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38(10): 841-863. Please cite final published version of article. Abstract: This article uses Burma/Myanmar from 1948 to 2011 as a within-case analysis to explore why some armed insurgent groups agree to ceasefires while others do not. Analyzing 33 armed groups it finds that longer-lived groups were less likely to agree to ceasefires with the military government between 1989 and 2011. The article uses this within-case variation to understand what characteristics would make an insurgent group more or less likely to agree to a ceasefire. The article identifies four armed groups for more in-depth qualitative analysis to understand the roles of the administration of territory, ideology, and legacies of distrust with the state as drivers of the decision to agree to or reject a ceasefire. Running head: Ceasefires in Burma/Myanmar 1 Between independence from Britain in 1948 and a tentative transition to a less militaristic regime in 2011, the central government of Burma/Myanmar had to contend with dozens of armed insurgent groups. Over time new groups formed, old ones were defeated or gave up, and existing ones changed demands, allied with each other, splintered from parent insurgencies or changed form. During this period the central government presented itself to the armed insurgents in at least four different forms: a weak parliamentary regime (1948-1958), a military ‘caretaker’ government (1958-1960), a socialist-military regime (1962-1988) and a military junta (1988-2011). -

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER July 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Militias in Myanmar

Militias in Myanmar John Buchanan July 2016 Acknowledgement The author would like to acknowledge the many people who assisted in this project, particularly those who generously shared their thoughts and experiences about the many topics covered in this report. I would also like to thank my friends and colleagues who took the time to provide comments and feedback on earlier drafts of this report. These include Matthew Arnold, Patrick Barron, Kim Jolliffe, Paul Keenan, David Mathieson, Brian McCartan, Kim Ninh, Andrew Selth and Martin Smith. Finally, I would also like to express my appreciation to friends from Burma who assisted with translation and data collection. About the Author John Buchanan is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Washington. His interest in Southeast Asia dates back over two decades. His most recent publication is Developing Disparity: Regional Investment in Burma’s Borderlands for the Transnational Institute. About The Asia Foundation The Asia Foundation is a nonprofit international development organization committed to improving lives across a dynamic and developing Asia. Informed by six decades of experience and deep local expertise, our programs address critical issues affecting Asia in the 21st century—governance and law, economic development, women's empowerment, environment, and regional cooperation. In addition, our Books for Asia and professional exchanges are among the ways we encourage Asia’s continued development as a peaceful, just, and thriving region of the world. Headquartered in San Francisco, The Asia Foundation works through a network of offices in 18 Asian countries and in Washington, DC. Working with public and private partners, the Foundation receives funding from a diverse group of bilateral and multilateral development agencies, foundations, corporations, and individuals. -

Why Burma's Peace Efforts Have Failed to End Its Internal Wars

PEACEWORKS Why Burma’s Peace Efforts Have Failed to End Its Internal Wars By Bertil Lintner NO. 169 | OCTOBER 2020 Making Peace Possible NO. 169 | OCTOBER 2020 ABOUT THE REPORT Supported by the Asia Center’s Burma program at the United States Institute of Peace to provide policymakers and the general public with a better understanding of Burma’s eth- PEACE PROCESSES nic conflicts, this report examines the country’s experiences of peace efforts and why they have failed to end its wars, and suggests ways forward to break the present stalemate. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Bertil Lintner has covered Burma’s civil wars and related issues, such as Burmese pol- itics and the Golden Triangle drug trade, for nearly forty years. Burma correspondent for the Far Eastern Economic Review from 1982 to 2004, he now writes for Asia Times and is the author of several books about Burma’s civil war and ethnic strife. Cover photo: A soldier from the Myanmar army provides security as ethnic Karens attend a ceremony to mark Karen State Day in Hpa-an, Karen State, on November 7, 2014. (Photo by Khin Maung Win/AP) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2020 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No.