The Scramble for Rakhine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

Arakan Army, AA)

Division de l’information, de la documentation et des recherches – DIDR 9 avril 2021 Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Armée de l’Arakan (Arakan Army, AA) Avertissement Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine, a été élaboré par la DIDR en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière et ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Arakan Army, (AA) Table des matières 1. Principales caractéristiques de l’Arakan Army ................................................................................ 3 1.1. Une organisation liée à la KIA et à l’UWSA ............................................................................. 3 1.2. Relations avec les autres organisations politico-militaires ...................................................... 3 2. Les opérations armées de l’AA ont entraîné des représailles massives ......................................... 4 3. Les interventions de l’AA à des fins logistiques dans les villages ................................................... 5 4. Enlèvements -

New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State?

CRS INSIGHT New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State? February 15, 2019 (IN11046) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) Approximately 250 Chin and Rakhine refugees entered into Bangladesh's Bandarban district in the first week of February, trying to escape the fighting between Burma's military, or Tatmadaw, and one of Burma's newest ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the Arakan Army (AA). Bangladesh's Foreign Minister Abdul Momen summoned Burma's ambassador Lwin Oo to protest the arrival of the Rakhine refugees and the military clampdown in Rakhine State. Bangladesh has reportedly closed its border to Rakhine State. U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee released a press statement on January 18, 2019, indicating that heavy fighting between the AA and the Tatmadaw had displaced at least 5,000 people. She also called on the Rakhine State government to reinstate the access for international humanitarian organizations. The Conflict Between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw The AA was formed in Kachin State in 2009, with the support of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). In 2015, the AA moved some of its soldiers from Kachin State to southwestern Chin State, and began attacking Tatmadaw security bases in Chin State and northern Rakhine State (see Figure 1). In late 2017, the AA shifted more of its operations into northeastern Rakhine State. According to some estimates, the AA has approximately 3,000 soldiers based in Chin and Rakhine States. Figure 1. Reported Clashes between Arakan Army and Tatmadaw Source: CRS, utilizing data provided by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). -

Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar

Policy Studies 71 Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar Matthew J. Walton and Susan Hayward Contesting Buddhist Narratives Democratization, Nationalism, and Communal Violence in Myanmar About the East-West Center The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. Established by the US Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for infor- mation and analysis on critical issues of common concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. The Center’s 21-acre Honolulu campus, adjacent to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, is located midway between Asia and the US main- land and features research, residential, and international conference facilities. The Center’s Washington, DC, office focuses on preparing the United States for an era of growing Asia Pacific prominence. The Center is an independent, public, nonprofit organization with funding from the US government, and additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, foundations, corporations, and govern- ments in the region. Policy Studies an East-West Center series Series Editors Dieter Ernst and Marcus Mietzner Description Policy Studies presents original research on pressing economic and political policy challenges for governments and industry across Asia, About the East-West Center and for the region's relations with the United States. Written for the The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding policy and business communities, academics, journalists, and the in- among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the formed public, the peer-reviewed publications in this series provide Pacifi c through cooperative study, research, and dialogue. -

Global Day of Prayer for 2020

GLOBAL DAY OFBURMA PRAYER FOR 2020 PRAYER AND ACTION BEYOND BORDERS:ZAU SENG, KACHIN MEDIC, VIDEOGRAPHER, AND FOLLOWER OF JESUS, GIVES HIS LIFE IN SYRIA 1 In this Issue Burma Overview 4 Burma Map 5 More Setbacks, Less Progress Stories of Love and Service 6 To Love is to Act 7 Show Another Way 11 North Star in a Dark Place Ethnic Area Updates 12 Arakan State 14 Chin State 15 Naga Hills 16 Northern Burma 18 Southern Shan State 19 Karenni State 20 Wa State 23 Karen State Praying For 24 Voices from Burma 26 Providing Care, Giving Hope 27 Justice Moves Forward 28 In Memoriam Pictured on this page: David Eubank and Pastor Edmund baptize one of five students who asked to be baptized at the conclusion of FBR training, December 2018. The Global Day of Prayer for Burma happens every year on the second Sunday of March. Please join us in praying for Burma. For more information, email [email protected]. Thanks to Acts Co. for its support and printing of this magazine. This magazine was produced by Christians Concerned for Burma (CCB). All text copyright CCB 2020. Design and layout by FBR Publications. All rights reserved. This magazine may be reproduced if proper credit is given to text and photos. All photos copyright Free Burma Rangers (FBR) unless otherwise noted. Scripture portions quoted are taken from the NIV unless otherwise noted. Christians Concerned for Burma (CCB), PO Box 392, Chiang Mai, 50000, THAILAND www.prayforburma.org [email protected] 2 As we see the innocent suffer and those who serve them die, it makes me ask: what difference does prayer make? I don’t know all the answers, but I do know that prayer changes my heart. -

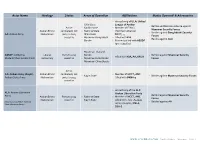

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

Myanmar in 2020

MARIE-EVE RENY Myanmar in 2020 Citizens Have Voted for the Democratic Transition to Continue, but Democracy Remains Far Ahead Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/as/article-pdf/61/1/138/455584/as.2021.61.1.138.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 ABSTRACT The NLD was reelected in 2020 with more seats than it won in 2015. Myanmar’s transition is not regressing, but many priorities remain before the state truly democratizes: conducting transparent trials of military officers who were involved in the killings of Rohingyas, solving the conflict between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw in Rakhine State, ensuring that enduring armed conflicts do not undermine citizens’ ability to vote, making sure the National Ceasefire Agreement prevents the resurgence of old animosities, demilitarizing the constitution, and restraining the military’s ability to sue opposition for defamation. KEYWORDS: national elections, armed conflicts, conflict resolution, democratic transition, foreign policy ELECTIONS On November 8, 2020, Myanmar held its second democratic national elec- tions since the beginning of its political transition. The National League for Democracy (NLD) won a majority of seats it contested in the bicameral national legislature (399 of 476), and more seats than in 2015 (390). Its campaign priorities included reforming the constitution, creating a federa- tion, and conflict resolution with non-state armed groups. Most of its prior- ities were the same as in 2015. Although 87 parties competed in the elections, MARIE-EVE RENY is a Hundred Talents Researcher in the Department of Sociology, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. Her report is based on the Irrawaddy’s coverage of events in Myanmar in 2020, and to a limited extent, that of Frontier and Myanmar Times. -

Finding an Endgame in Kachin State the KIO’S Strategies for Finding a Resolution to the Conflict

EBO Background Paper - No .3 | 2018 September 2018 AUTHOR | Paul Keenan Finding an Endgame in Kachin State The KIO’s strategies for finding a resolution to the conflict Since 9 June 2011, Kachin State has seen open (CEFU). The Committee’s purpose was to conflict between the Kachin Independence Army consolidate a political front at a time when the and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military). The Kachin ceasefire groups faced perceived imminent attacks Independence Organisation had signed a ceasefire by the Tatmadaw. However, in November 2010 agreement with the regime in 1994 and since then shortly after the Myanmar elections, the political had lived in relative peace until the ceasefire was grouping was transformed into a military united broken by the Tatmadaw in June 2011. front. At a conference held from the 12-16 February 2011, CEFU declared its dissolution and the The increased territorial infractions by the formation of the United Nationalities Federal Tatmadaw combined with economic exploitation Council (UNFC). The UNFC, which was at that time by China in Kachin territory, especially the comprised of 12 ethnic organisations1, stated that: construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam, left the Kachin Independence Organisation with very The goal of the UNFC is to establish the little alternative but to return to armed resistance future Federal Union (of Myanmar) and to prevent further abuses of its people and their the Federal Union Army is formed for territory’s natural resources. Despite this, however, giving protection to the people of the the political situation since the beginning of country.2 hostilities has changed significantly. -

Burma: Key Issues in 2021

Updated January 21, 2021 Burma: Key Issues in 2021 Burma (Myanmar) has been embroiled in a low-grade civil for ending the civil war. A December 2020 JMC meeting war between its military, known as the Tatmadaw, and over made little progress on both issues. 20 ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) as far back as 1962, Representatives of the Union Government, the Tatmadaw, when the Tatmadaw overthrew a democratically elected civilian government. In 2011, the Tatmadaw handed power and the EAOs who have signed the 2015 ceasefire agreement participated in a peace conference in August over to a hybrid civilian-military Union Government based 2020, but the non-signatory EAOs did not attend. The on a 2008 constitution largely written by the Tatmadaw. The Obama and Trump Administrations attempted to foster conference produced no major results. Burma’s return to democratic civilian rule by supporting the Figure 1. Intensity of Fighting by Ethnic State (2020) Union Government and its current leader Aung San Suu Kyi. Major Events in 2020 For Burma, the year 2020 was marked by the continued intensification of the country’s civil war, stalled peace talks, marred parliamentary elections, investigations of allegations of genocide, and the outbreak of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Aung San Suu Kyi and her political party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), retained a supermajority following the November parliamentary elections, securing five more years in office. Civil War Burma’s civil war intensified in 2020, despite the Tatmadaw declaring a unilateral ceasefire covering most of the nation, except Rakhine State (see Figure 1). -

Rohingya Crisis in Southeast Asia: the Jihadi Dimension

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Rohingya Crisis in Southeast Asia: The Jihadi Dimension Jasminder Singh 2017 Jasminder Singh. (2017). Rohingya Crisis in Southeast Asia: The Jihadi Dimension. (RSIS Commentaries, No. 069). RSIS Commentaries. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/82802 Nanyang Technological University Downloaded on 30 Sep 2021 06:40:49 SGT Rohingya Crisis in Southeast Asia: The Jihadi Dimension By Jasminder Singh Synopsis The Rohingya problem is an old one. After nearly 70 years, the problem has been greatly aggravated by rising sectarian violence by radical Buddhist groups against Muslims and the involvement of transnational terrorist groups such as Al Qaeda and the self-proclaimed Islamic State. Commentary THE ROHINGYA crisis in Myanmar has a long history. Following Burma’s independence in January 1948, a Rohingya-based insurgency broke out in northern Arakan, now known as Rakhine State, with the aim of integrating with East Pakistan, present-day Bangladesh. By the late 1950s, the mujahidin-oriented insurgency was crushed by the Burmese Army. Since the 1970s, various Islamist groups have surfaced to take up the cudgels of liberation, either to gain greater autonomy or outright independence. The key groups championing the Rohingya struggle include the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation, the Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front and Arakan National Liberation Organisation. Following the success of the Afghan Mujahidin in defeating the Soviets, since the 1980s, extremist jihadi-oriented groups have espoused violent struggle against Myanmar, often with the support of Af-Pak based radical groups and by the late 1990s onwards, groups affiliated with Al Qaeda and Islamic State. -

The Indonesia's Urgency on Adopting New Approach on Comprehensive Prevention in Countering Terrorism Strategy

The Indonesia’s Urgency on Adopting New Approach on Comprehensive Prevention ... 103 The Indonesia’s Urgency on Adopting New Approach on Comprehensive Prevention in Countering Terrorism Strategy: Lesson Learnt from the Mako Detention Facility’s Riot and East Java Bombs Indah P. Amaritasari Universitas Bhayangkara Jakarta Raya E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Indonesia dihadapkan pada rangkaian serangan teror pada Mei 2018, antara lain: peristiwa kerusuhan disertai penyanderaan polisi oleh narapidana terorisme di Rutan Mako Brimob Kelapa Dua, Depok pada 8 Mei 2018, aksi teror bom bunuh diri terjadi di tiga gereja secara bersamaan pada Minggu pagi, 13 Mei, bom bunuh diri di pintu masuk Polrestabes Surabaya pada 14 Mei. Rangkaian peristiwa ini menunjukkan bahwa terorisme masih menjadi ancaman keamanan di Indonesia. Sejumlah serangan teror di Indonesia diyakini dilakukan oleh kelompok teroris yang berbai’at ke ISIS. Indonesia dalam rangka penanggulangan terhadap acaman terorisme telah melakukan sejumlah pendekatan baik soft approach maupun hard approach dengan menggunakan model criminal justice. Namun demikian, Indonesia melakukan modifikasi pendekatan criminal justice dengan melibatkan peran militer. Oleh karena itu, diperlukan pemahaman terhadap berbagai bentuk yang diasosiasikan dengan hard approach? dan bagaimana strategi baru yang juga perlu dipertimbangkan melihat ancaman yang ada? Tulisan ini mencoba mengeksplorasi berbagai kemungkinan strategi baru yang diadopsi Indonesia sebagai kelanjutan dari respon PBB terhadap -

CAUGHT in the CROSSFIRE: Witness and Survivor Accounts of Burma Army Attacks and Human Rights Violations in Arakan State

CAUGHT IN THE CROSSFIRE: Witness and Survivor Accounts of Burma Army Attacks and Human Rights Violations in Arakan State WARNING: This report contains graphic photos Caught in the Crossfire At right: Photos of victims of a Burma Army attack in Arakan State on April 13, 2020. For more information on this particular airstrike, please see the photo on page 9. Caught in the Crossfire Free Burma Rangers About this Report This report is the result of 178 interviews conducted, recorded, and translated by Arakan members of the Free Burma Rangers (FBR). The Rangers conducted the interviews during 2019 and submitted the translations and corresponding videos and photos in June 2020. These interviews represent a fraction of the total incidences of Burma Army abuse that is being perpetrated on a grand scale in Arakan State. In March 2020, the Burmese government designated the Arakan Army as a terrorist organization. With this designation, locals fear that the Burmese soldiers will increase the use of torture and detention against civilians in Arakan State with total impunity. Acknowledgements FBR would like to acknowledge and thank the Arakan Rangers for their hard work and dedication in collecting these interviews regarding the ongoing conflict in Arakan State. This report would not be possible without their commitment to getting the news out. We are also grateful to the witnesses who shared their stories and without whose courage in coming forward this report would not have been possible. FBR continues to stand with the Arakan people and others under attack in northern Arakan State as well as Chin State where this particular conflict has spilled into.