Myanmar in 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations. Morten Bergsmo; Wolfgang Kaleck; Kyaw Yin Hlaing. Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, 40, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, pp.177-227, 2020, Publication Series, 978-82-8348-134-1. hal- 02997366 HAL Id: hal-02997366 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02997366 Submitted on 10 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors) E-Offprint: Jacques P. Leider, “The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations”, in Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors), Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPub- lisher, Brussels, 2020 (ISBNs: 978-82-8348-133-4 (print) and 978-82-8348-134-1 (e- book)). This publication was first published on 9 November 2020. TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site https://www.toaep.org which uses Persistent URLs (PURLs) for all publications it makes available. -

Migration from Bengal to Arakan During British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin

Occasional Paper Series Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin 2019 Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher Brussels This and other publications in TOAEP’s Occasional Paper Series may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site http://toaep.org, which uses Persistent URLs for all publications it makes available (such PURLs will not be changed). This publication was first published on 6 December 2019. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2019 All rights are reserved. You may read, print or download this publication or any part of it from http://www.toaep.org/ for personal use, but you may not in any way charge for its use by others, directly or by reproducing it, storing it in a retrieval system, transmitting it, or utilising it in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, in whole or in part, without the prior permis- sion in writing of the copyright holder. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the copyright holder. You must not circulate this publication in any other cover and you must impose the same condition on any ac- quirer. You must not make this publication or any part of it available on the Internet by any other URL than that on http://www.toaep.org/, without permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-82-8348-150-1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 2 2. Setting the Scene: The 1911, 1921 and 1931 Censuses of British Burma ............................ -

Arakan Army, AA)

Division de l’information, de la documentation et des recherches – DIDR 9 avril 2021 Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Armée de l’Arakan (Arakan Army, AA) Avertissement Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine, a été élaboré par la DIDR en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière et ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Myanmar / Birmanie : L’Arakan Army, (AA) Table des matières 1. Principales caractéristiques de l’Arakan Army ................................................................................ 3 1.1. Une organisation liée à la KIA et à l’UWSA ............................................................................. 3 1.2. Relations avec les autres organisations politico-militaires ...................................................... 3 2. Les opérations armées de l’AA ont entraîné des représailles massives ......................................... 4 3. Les interventions de l’AA à des fins logistiques dans les villages ................................................... 5 4. Enlèvements -

Burma/Bangladesh Burmese Refugees in Bangladesh: Still No Durable Solution

May 2000 Vol 12., No. 3 (C) BURMA/BANGLADESH BURMESE REFUGEES IN BANGLADESH: STILL NO DURABLE SOLUTION I. SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................................................................2 Recommendations ..................................................................................................................................................3 To the Government of Burma.............................................................................................................................3 To the Government of Bangladesh.....................................................................................................................4 To the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees ............................................................4 II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND .........................................................................................................................5 World War II, Independence, and Rohingya Flight ...............................................................................................6 Operation Nagamin and the 1970s Exodus ............................................................................................................7 Flight in the 1990s..............................................................................................................................................8 Continued Obstacles to Repatriation ..................................................................................................................8 -

New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State?

CRS INSIGHT New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State? February 15, 2019 (IN11046) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) Approximately 250 Chin and Rakhine refugees entered into Bangladesh's Bandarban district in the first week of February, trying to escape the fighting between Burma's military, or Tatmadaw, and one of Burma's newest ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the Arakan Army (AA). Bangladesh's Foreign Minister Abdul Momen summoned Burma's ambassador Lwin Oo to protest the arrival of the Rakhine refugees and the military clampdown in Rakhine State. Bangladesh has reportedly closed its border to Rakhine State. U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee released a press statement on January 18, 2019, indicating that heavy fighting between the AA and the Tatmadaw had displaced at least 5,000 people. She also called on the Rakhine State government to reinstate the access for international humanitarian organizations. The Conflict Between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw The AA was formed in Kachin State in 2009, with the support of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). In 2015, the AA moved some of its soldiers from Kachin State to southwestern Chin State, and began attacking Tatmadaw security bases in Chin State and northern Rakhine State (see Figure 1). In late 2017, the AA shifted more of its operations into northeastern Rakhine State. According to some estimates, the AA has approximately 3,000 soldiers based in Chin and Rakhine States. Figure 1. Reported Clashes between Arakan Army and Tatmadaw Source: CRS, utilizing data provided by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations -

Global Day of Prayer for 2020

GLOBAL DAY OFBURMA PRAYER FOR 2020 PRAYER AND ACTION BEYOND BORDERS:ZAU SENG, KACHIN MEDIC, VIDEOGRAPHER, AND FOLLOWER OF JESUS, GIVES HIS LIFE IN SYRIA 1 In this Issue Burma Overview 4 Burma Map 5 More Setbacks, Less Progress Stories of Love and Service 6 To Love is to Act 7 Show Another Way 11 North Star in a Dark Place Ethnic Area Updates 12 Arakan State 14 Chin State 15 Naga Hills 16 Northern Burma 18 Southern Shan State 19 Karenni State 20 Wa State 23 Karen State Praying For 24 Voices from Burma 26 Providing Care, Giving Hope 27 Justice Moves Forward 28 In Memoriam Pictured on this page: David Eubank and Pastor Edmund baptize one of five students who asked to be baptized at the conclusion of FBR training, December 2018. The Global Day of Prayer for Burma happens every year on the second Sunday of March. Please join us in praying for Burma. For more information, email [email protected]. Thanks to Acts Co. for its support and printing of this magazine. This magazine was produced by Christians Concerned for Burma (CCB). All text copyright CCB 2020. Design and layout by FBR Publications. All rights reserved. This magazine may be reproduced if proper credit is given to text and photos. All photos copyright Free Burma Rangers (FBR) unless otherwise noted. Scripture portions quoted are taken from the NIV unless otherwise noted. Christians Concerned for Burma (CCB), PO Box 392, Chiang Mai, 50000, THAILAND www.prayforburma.org [email protected] 2 As we see the innocent suffer and those who serve them die, it makes me ask: what difference does prayer make? I don’t know all the answers, but I do know that prayer changes my heart. -

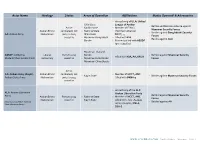

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

Understanding China's Response to the Rakhine Crisis

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Adrienne Joy Following attacks on police posts by a Rohingya militia in August 2017, Burmese military attacks on the predominantly Muslim Rohingya population in Rakhine State have forced more than six hundred thousand Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. Supported by the Asia Center at the United States Institute Understanding China’s of Peace, this report examines China’s interests and influence in Rakhine State and its continuing support of the Burmese government and military during the ongoing humanitarian crisis. Response to the Rakhine ABOUT THE AUTHOR Adrienne Joy is a Yangon-based independent consultant, Crisis specializing on the Burma’s peace process and China-Burma relations. Her work has included extensive analysis on the dynamics between ethnic armed groups, the government, and the Tatmadaw. Summary • A major humanitarian crisis has unfolded in Burma’s Rakhine State since August 2017, after attacks by a Rohingya armed group on police posts were followed by retaliatory attacks against the Rohingya population. • More than six hundred thousand Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh, and reports of human rights abuses have sparked widespread international condemnation, particularly from West- ern nations and Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) countries. • In contrast, China’s response has been largely supportive of the Burmese government—in effect affirming Burma’s characterization of the attacks as “terrorism.” Military cooperation between the two states has also been reaffirmed. • Publicly stating that the root cause of conflict in Rakhine is economic underdevelopment, China has promoted its large-scale infrastructure investments in the state (including a deep-sea port, and oil and gas pipelines) as a means of conflict resolution. -

Conflict and Mass Violence in Arakan (Rakhine State): the 1942 Events and Political Identity Formation

Jacques P. Leider (Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient, Yangon) February 2017 Conflict and mass violence in Arakan (Rakhine State): the 1942 events and political identity formation Following the Japanese invasion of Lower Burma in early 1942, the British administration in Arakan1 collapsed in late March/early April. In a matter of days, communal violence broke out in the rural areas of central and north Arakan (Akyab and Kyaukphyu districts). Muslim villagers from Chittagong who had settled in Arakan since the late 19th century were attacked, driven away or killed in Minbya, Myebon, Pauktaw and other townships of central Arakan. A few weeks later, Arakanese Buddhist villagers living in the predominantly Muslim townships of Maungdaw and Buthidaung were taken on by Chittagonian Muslims, their villages destroyed and people killed in great numbers. Muslims fled to the north while Buddhists fled to the south and from 1942 to 1945, the Arakanese countryside was ethnically divided between a Muslim north and a Buddhist south. Several thousand Buddhists and Muslims were relocated by the British to camps in Bengal. The unspeakable outburst of violence has been described with various expressions, such as “massacre”, “bitter battle” or “communal riot” reflecting different interpretations of what had happened. In the 21st century, the description “ethnic cleansing” would likely be considered as a legally appropriate term. Buddhists and Muslims alike see the 1942 violence as a key moment of their ongoing ethno-religious and political divide. The waves of communal clashes of 1942 have been poorly documented, sparsely investigated and rarely studied.2 They are not recorded in standard textbooks on Burma/Myanmar and, surprisingly, they were even absent from contemporary reports and articles that described Burma’s situation during and after World War 1 Officially named Rakhine State after 1989. -

Finding an Endgame in Kachin State the KIO’S Strategies for Finding a Resolution to the Conflict

EBO Background Paper - No .3 | 2018 September 2018 AUTHOR | Paul Keenan Finding an Endgame in Kachin State The KIO’s strategies for finding a resolution to the conflict Since 9 June 2011, Kachin State has seen open (CEFU). The Committee’s purpose was to conflict between the Kachin Independence Army consolidate a political front at a time when the and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military). The Kachin ceasefire groups faced perceived imminent attacks Independence Organisation had signed a ceasefire by the Tatmadaw. However, in November 2010 agreement with the regime in 1994 and since then shortly after the Myanmar elections, the political had lived in relative peace until the ceasefire was grouping was transformed into a military united broken by the Tatmadaw in June 2011. front. At a conference held from the 12-16 February 2011, CEFU declared its dissolution and the The increased territorial infractions by the formation of the United Nationalities Federal Tatmadaw combined with economic exploitation Council (UNFC). The UNFC, which was at that time by China in Kachin territory, especially the comprised of 12 ethnic organisations1, stated that: construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam, left the Kachin Independence Organisation with very The goal of the UNFC is to establish the little alternative but to return to armed resistance future Federal Union (of Myanmar) and to prevent further abuses of its people and their the Federal Union Army is formed for territory’s natural resources. Despite this, however, giving protection to the people of the the political situation since the beginning of country.2 hostilities has changed significantly.