Understanding China's Response to the Rakhine Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Government's Initiatives for Industrial Development in Myanmar

CHAPTER 2 New Government’s Initiatives for Industrial Development in Myanmar Aung Min and Toshihiro KUDO This chapter should be cited as: Aung Min and Kudo, K., 2012. “New Government’s Initiatives for Industrial Development in Myanmar.” In Economic Reforms in Myanmar: Pathways and Prospects, edited by Hank Lim and Yasuhiro Yamada, BRC Research Report No.10, Bangkok Research Center, IDE-JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. Chapter 2 New Government’s Initiatives for Industrial Development in Myanmar Aung Min and Toshihiro KUDO Abstract Since 1988, when the State Law and Order Restoration Council (military government) assumed state responsibility, the market has been partially opened to the outside world. Myanmar's industrialization has shown little progress as the previous government’s1 policies and poor international relations hampered FDI inflows. As the new “elected” government took office in 2011, significant changes in policies have taken place and this paper intends to highlight the efforts of the new government in its attempt to enhance industrial development. The paper assesses the performance of related union-level ministries and regional governments towards industrial development through establishing industrial zones in all states and regions, except the Chin and Kayah states. The establishment of seven new industrial zones and extension of 18 existing industrial zones is seen to have a positive effect on industrial development, although improvements in infrastructural facilities need to be realized. Introducing the SME Service Centre in Yangon and SME financing schemes enables the firms to obtain loans from the newly named Small and Medium Industrial Development Bank (SMIDB)2, thus contributing to SME development to some extent. -

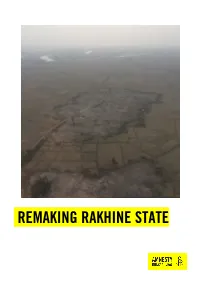

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Township Map - Rakhine State 92° E 93° E 94° E Tilin 95° E Township Myaing Yesagyo Pauk Township Township Bhutan Bangladesh Kyaukhtu !( Matupi Mindat Mindat Township India China Township Pakokku Paletwa Bangladesh Pakokku Taungtha Samee Ü Township Township !( Pauk Township Vietnam Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Nyaung-U !( Paletwa Saw Township Saw Township Ngathayouk !( Bagan Laos Maungdaw !( Buthidaung Seikphyu Township CHIN Township Township Nyaung-U Township Kanpetlet 21° N 21° Township MANDALAYThailand N 21° Kyauktaw Seikphyu Chauk Township Buthidaung Kyauktaw KyaukpadaungCambodia Maungdaw Chauk Township Kyaukpadaung Salin Township Mrauk-U Township Township Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Ponnagyun Township Township Minbya Rathedaung Sidoktaya Township Township Yenangyaung Yenangyaung Sidoktaya Township Minbya Pwintbyu Pwintbyu Ponnagyun Township Pauktaw MAGWAY Township Saku Sittwe !( Pauktaw Township Minbu Sittwe Magway Magway .! .! Township Ngape Myebon Myebon Township Minbu Township 20° N 20° Minhla N 20° Ngape Township Ann Township Ann Minhla RAKHINE Township Sinbaungwe Township Kyaukpyu Mindon Township Thayet Township Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Mindon Township !( Bay of Bengal Ramree Kamma Township Kamma Ramree Toungup Township Township 19° N 19° N 19° Munaung Toungup Munaung Township BAGO Padaung Township Thandwe Thandwe Township Kyangin Township Myanaung Township Kyeintali !( 18° N 18° N 18° Legend ^(!_ Capital Ingapu .! State Capital Township Main Town Map ID : MIMU1264v02 Gwa !( Other Town Completion Date : 2 November 2016.A1 Township Projection/Datum : Geographic/WGS84 Major Road Data Sources :MIMU Base Map : MIMU Lemyethna Secondary Road Gwa Township Boundaries : MIMU/WFP Railroad Place Name : Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) translated by MIMU AYEYARWADY Coast Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Township Boundary www.themimu.info Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Yegyi Ngathaingchaung !( State/Region Boundary 2016. -

Village Tracts of Mrauk - U Township Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Village Tracts of Mrauk - U Township Rakhine State 93°0’E 93°10’E 93°20’E Kyauk Kyat Taung U Pyi Lone Gyi Ei Vi Ti Kar Kyi 20°48’N 20°48’N Yar Pyin Hteik Wa Pyin Pauk Pin Kwin Sin Ke Shar Yay Kan Sauk Pyin Oe Htein Pyaing Cha Tha Pyay Ma Kyar Se Kan Ta u n g M y in t Shwe Kyin Cheik Chaung Pyin Oke Kan Bu Ywet Gwa Son Ma Nyoe Hpa Yar Gyi Tein Nyo Byoke Chaung Maw Taung Taik Wet Hla Lay Hnyin Kone Baung Taung Tin Htein Kan 20°40’N Way Thar Li Gone Kyun 20°40’N Sin Oe Pya Hla Than Thin Pan Kaing Chaung Ywar Haung Taw MRAUK - U Kin Chaung Ah Yet Thay Ma Htan Ma Rit Na Kan Pu Zun Hpe Mrauk-U Myet Yaik Kyun Bar Nyo Kin Seik Urban Pu Rein Cha Yar Shauk Ta w Bwe i Ku Lar Ka Pon Kyun Baung Dut Paung Htoke Ka Da Wa Tan Tin Pi Pin Yin Than Ta Yar Ku Toe Nan Kya 20°32’N Naung Min 20°32’N Ma Har Kon Baung Su Yit Chaung Kyay Htee Oke Kar Kyaw Pin Lel Lay Hnyin Thar Pyar Te Yin Thei Myaung Than Shin Pyin Bway Maung Hna Ma Let Pan Taw Bu Ta Lone Zee Zar Kywe Te Koke Ka Rit Htaunt Ah Kyee Kant Tha Ri Set Thar Ta w M a Let Kyein Than Chi Nga Me Pyin Ye Hpyar Chaung Pyaung Paw Nyaung Pin Lel Nan Tet Ah Lel Chaung Kyar Kan Chin Shin Yae Zee Pin Gyi Hpa Yar Myar Tha Baw Mandalay Magway Nyaung 20°24’N Pin Lel (Ku Thar Yar Kone 20°24’N Lar Pone) K Thu Nge Taw Bay of Bengal Rakhine Bago Nat Chaung Minbya Kilometers Ayeyarwady 0482 Yangon 93°0’E 93°10’E 93°20’E Map ID: MIMU575v01 Legend Data Sources : GLIDE Number: TC-2010-000211-MMR Road Village Tract Boundaries Cyclone BASE MAP - MIMU Creation Date: 15 November 2010. -

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations. Morten Bergsmo; Wolfgang Kaleck; Kyaw Yin Hlaing. Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, 40, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, pp.177-227, 2020, Publication Series, 978-82-8348-134-1. hal- 02997366 HAL Id: hal-02997366 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02997366 Submitted on 10 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors) E-Offprint: Jacques P. Leider, “The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations”, in Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors), Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPub- lisher, Brussels, 2020 (ISBNs: 978-82-8348-133-4 (print) and 978-82-8348-134-1 (e- book)). This publication was first published on 9 November 2020. TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site https://www.toaep.org which uses Persistent URLs (PURLs) for all publications it makes available. -

Migration from Bengal to Arakan During British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin

Occasional Paper Series Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin 2019 Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher Brussels This and other publications in TOAEP’s Occasional Paper Series may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site http://toaep.org, which uses Persistent URLs for all publications it makes available (such PURLs will not be changed). This publication was first published on 6 December 2019. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2019 All rights are reserved. You may read, print or download this publication or any part of it from http://www.toaep.org/ for personal use, but you may not in any way charge for its use by others, directly or by reproducing it, storing it in a retrieval system, transmitting it, or utilising it in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, in whole or in part, without the prior permis- sion in writing of the copyright holder. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the copyright holder. You must not circulate this publication in any other cover and you must impose the same condition on any ac- quirer. You must not make this publication or any part of it available on the Internet by any other URL than that on http://www.toaep.org/, without permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-82-8348-150-1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 2 2. Setting the Scene: The 1911, 1921 and 1931 Censuses of British Burma ............................ -

The Protection of Human Rights of Rohingya in Myanmar: the Role of the International Community

Department of Political Science Master in International Relations Chair of: International Organization and Human Rights The Protection of Human Rights of Rohingya in Myanmar: The Role of The International Community CANDIDATE: SUPERVISOR: Riccardo Marzoli Professor Roberto Virzo No. 623322 CO-SUPERVISOR: Professor Francesco Cherubini Academic year: 2014/2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………...p.5 1.THE PAST: THE HISTORICAL PRESENCE OF ROHINGYA IN RAKHINE STATE. SINCE THE ORIGINS TO 1978…………………………………………………………. 9 1.1.REWRITING HISTORY: CONFLICTING VERSIONS OF BURMESE AND INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ………………………………………………………. 10 1.1.1 ETIMOLOGY OF THE TERMS…………………………………………………………………. 13 1.2. ANCIENT HISTORY OF ARAKAN AND FIRST ISLAMIC CONTACTS……… 14 1.3 CHANDRAS DINASTY AND THE ORIGINS OF THE MAGHS…………………16 1.4. MIN SAW MUN AND THE ARAKANESE KINGS WITH MUSLIM TITLES: THE SIGN OF A WIDESPREAD ISLAMIC INFLUENCE……………………………………...17 1.4.1 DIFFERENT VISIONS: WHICH ROLE FOR ROHINGYA IN MYANMAR?...................19 1.5 A NEW INFLUX: FRATRICIDAL WARS BETWEEN THE HEIRS OF THE MUGHALS’ THRONE AND THE ROLE OF THE KAMANS……………………………20 1.6 DIFFERENT WAVES OF MUSLIM ENTRANCES TO ARAKAN………………...21 1.7 1781 THE ADVENT OF THE BURMANS. THE OCCUPATION BY BODAW PAYA AND THE PREMISES OF THE BRITISH DOMINANCE ………………………………..24 1.7.1 KING SANDA WIZAYA AND THE KAMANS IN RAMREE………………………………...24 1.7.2 THE END OF THE KINGDOM OF MRAUK-U AND THE ARRIVAL OF THE AVA ARMY……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….25 1.7.3 KING BERING’S SAGA AND THE ARAKANESE -

Burma/Bangladesh Burmese Refugees in Bangladesh: Still No Durable Solution

May 2000 Vol 12., No. 3 (C) BURMA/BANGLADESH BURMESE REFUGEES IN BANGLADESH: STILL NO DURABLE SOLUTION I. SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................................................................2 Recommendations ..................................................................................................................................................3 To the Government of Burma.............................................................................................................................3 To the Government of Bangladesh.....................................................................................................................4 To the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees ............................................................4 II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND .........................................................................................................................5 World War II, Independence, and Rohingya Flight ...............................................................................................6 Operation Nagamin and the 1970s Exodus ............................................................................................................7 Flight in the 1990s..............................................................................................................................................8 Continued Obstacles to Repatriation ..................................................................................................................8 -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations -

Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State

ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 1/2 RH PT Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State (Source: Myanmar Information Management Unit) http://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/State_Map_D istrict_Rakhine_MIMU764v04_23Oct2017_A4.pdf ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 2/2 RH PT Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Rakhine State 92° EBANGLADESH 93° E 94° E 95° E Pauk !( Kyaukhtu INDIA Mindat Pakokku Paletwa CHINA Maungdaw !( Samee Ü Taungpyoletwea Nyaung-U !( Kanpetlet Ngathayouk CHIN STATE Saw Bagan !( Buthidaung !( Maungdaw District 21° N THAILAND 21° N SeikphyuChauk Buthidaung Kyauktaw Kyauktaw Kyaukpadaung Maungdaw Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Mrauk-U Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Mrauk-U District Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Minbya Pwintbyu Sittwe DistrictPonnagyun Pauktaw Sittwe Saku !( Minbu Pauktaw .! Ngape .! Sittwe Myebon Ann Magway Myebon 20° N RAKHINE STATE Minhla 20° N Ann MAGWAY REGION Sinbaungwe Kyaukpyu District Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu !( Mindon Ramree Toungup Ramree Kamma 19° N 19° N Bay of Bengal Munaung Toungup Munaung Padaung Thandwe District BAGO REGION Thandwe Thandwe Kyangin Legend .! State/Region Capital Main Town !( Other Town Kyeintali !( 18° N Coast Line 18° N Map ID: MIMU764v04 Township Boundary Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 State/Region Boundary Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 International Boundary Data Sources: MIMU Gwa Base Map: MIMU Road Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Kyaukpyu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) Gwa translated by MIMU Maungdaw Mrauk-U Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Sittwe Ngathaingchaung Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Kilometers !( Thandwe 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 15 30 60 Yegyi 92° E 93° E 94° E 95° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Where There Is Police, There Is Persecution Government Security

Physicians for Where There is Police, Human Rights There is Persecution Government Security Forces and October 2016 Human Rights Abuses in Myanmar’s Northern Rakhine State An immigration officer inspects Rohingyas’ paperwork at a checkpoint in Rakhine State. About Physicians for Human Rights For 30 years, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has used science and medicine to document and call attention to mass atrocities and severe human rights violations. PHR is a global organization founded on the idea that health professionals, with their specialized skills, ethical duties, and credible voices, are uniquely positioned to stop human rights violations. PHR’s investigations and expertise are used to advocate for persecuted health workers and medical facilities under attack, prevent torture, document mass atrocities, and hold those who violate human rights accountable. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Introduction This report was written by Claudia Rader edited and Widney Brown, Physicians for prepared the report for 4 Methodology Human Rights (PHR) program publication. director, and is based on field 6 Background research conducted from November PHR would like to acknowledge 2015 to May 2016 in Myanmar the Bangladesh-based research 8 Findings (Rakhine State and Yangon) and team who contributed to the Bangladesh. study, design, and data collection 20 Discussion and also reviewed and edited the The report benefited from review report. PHR would also like to 24 Conclusion and by PHR leadership and staff, thank other external reviewers Recommendations including DeDe Dunevant, director who wish to remain anonymous. of communications, Donna McKay, 27 Endnotes MS, executive director, Marianne PHR is deeply indebted to the Møllmann, LLM, MSc, senior Rohingya and Rakhine people researcher, and Claudia Rader, MS, who were willing to share their content and marketing manager. -

Atrocity Crimes Against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, Myanmar

BEARING WITNESS REPORT NOVEMBER 2017 “THEY TRIED TO KILL US ALL” Atrocity Crimes against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, Myanmar SIMON-SKJODT CENTER FOR THE PREVENTION OF GENOCIDE United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Washington, DC www.ushmm.org The United States Holocaust Museum’s work on genocide and related crimes against humanity is conducted by the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide. The Simon-Skjodt Center is dedicated to stimulating timely global action to prevent genocide and to catalyze an international response when it occurs. Our goal is to make the prevention of genocide a core foreign policy priority for leaders around the world through a multipronged program of research, education, and public outreach. We work to equip decision makers, starting with officials in the United States but also extending to other governments and institutions, with the knowledge, tools, and institutional support required to prevent— or, if necessary, halt—genocide and related crimes against humanity. FORTIFY RIGHTS Southeast Asia www.fortifyrights.org Fortify Rights works to ensure and defend human rights for all. We investigate human rights violations, engage policy makers and others, and strengthen initiatives led by human rights defenders, affected communities, and civil society. We believe in the influence of evidence- based research, the power of strategic truth-telling, and the importance of working closely with individuals, communities, and movements pushing for change. We are an independent, nonprofit organization based in Southeast Asia and registered in the United States and Switzerland. The United State Holocaust Memorial Museum uses the name “Burma” and Fortify Rights uses the name “Myanmar” to describe the same country.