Atrocity Crimes Against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015

Rakhine State Needs Assessment September 2015 This document is published by the Center for Diversity and National Harmony with the support of the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund. Publisher : Center for Diversity and National Harmony No. 11, Shweli Street, Kamayut Township, Yangon. Offset : Public ation Date : September 2015 © All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Rakhine State, one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, has been plagued by communal problems since the turn of the 20th century which, coupled with protracted underdevelopment, have kept residents in a state of dire need. This regrettable situation was compounded from 2012 to 2014, when violent communal riots between members of the Muslim and Rakhine communities erupted in various parts of the state. Since the middle of 2012, the Myanmar government, international organisations and non-governmen- tal organisations (NGOs) have been involved in providing humanitarian assistance to internally dis- placed and conflict-affected persons, undertaking development projects and conflict prevention activ- ities. Despite these efforts, tensions between the two communities remain a source of great concern, and many in the international community continue to view the Rakhine issue as the biggest stumbling block in Myanmar’s reform process. The persistence of communal tensions signaled a need to address one of the root causes of conflict: crushing poverty. However, even as various stakeholders have attempted to restore normalcy in the state, they have done so without a comprehensive needs assessment to guide them. In an attempt to fill this gap, the Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH) undertook the task of developing a source of baseline information on Rakhine State, which all stakeholders can draw on when providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as when working on conflict prevention in the state. -

International Symposium on Oral Education and Research in Kitakyushu

Asia-Pacific Conference in Fukuoka 2018 International Symposium on Oral Education and Research in Kitakyushu Date: May 11th 2018 (Fri) Venue: Kyushu Dental University, Kitakyushu, Japan Organized by Kyushu Dental University Asia-Pacific Conference in Fukuoka 2018 International Symposium on Oral Education and Research in Kitakyushu Kyushu Dental University, Kitakyushu, Japan May 11th, 2018 Organizing Committee: Tatsuji Nishihara, President Kenshi Maki Tetsuro Konoo Katsumi Hidaka Keisuke Nakashima Kou Matsuo Yuji Seta Tatsuo Kawamoto Hiroshi Takeuchi Atsuko Nakamichi Naoki Kakudate Wataru Ariyoshi Koji Watanabe Organized by Kyushu Dental University 1 Table of Contents Welcome message 3 Program 4 International Symposium 6 Congratulatory speeches by guests of honor 8 International Symposium 11 Partnership Activities of Kyushu Dental University with Universities in Myanmar 14 Poster Presentations 16 * Young Investigator Award Competition 16-31 2 3 Welcome message Tatsuji Nishihara, D.D.S., Ph.D. Chairman and President Kyushu Dental University Welcome to Asia-Pacific Conference in Fukuoka 2018. It is our great honor and pleasure to inform the International Symposium on Oral Education and Research in Kitakyushu. I am inviting you to participate in this exciting conference with valuable information on Oral Education and Research of Asia-Pacific countries. We are delighted to announce the special lectures in this conference. Present state of dental education in Asian countries as well as Myanmar will be introduced by the invited distinguished speaker, Professor Dr. Paing Soe, M.D., Ph.D., President of Myanmar Dental Council, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. We are also very happy to hear on dental education system in Europe from Dr. -

Remaking Rakhine State

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

The Differences Between Sunni and Shia Muslims the Words Sunni and Shia Appear Regularly in Stories About the Muslim World but Few People Know What They Really Mean

Name_____________________________ Period_______ Date___________ The Differences Between Sunni and Shia Muslims The words Sunni and Shia appear regularly in stories about the Muslim world but few people know what they really mean. Religion is important in Muslim countries and understanding Sunni and Shia beliefs is important in understanding the modern Muslim world. The beginnings The division between the Sunnis and the Shia is the largest and oldest in the history of Islam. To under- stand it, it is good to know a little bit about the political legacy of the Prophet Muhammad. When the Prophet died in the early 7th Century he not only left the religion of Islam but also an Islamic State in the Arabian Peninsula with around one hundred thousand Muslim inhabitants. It was the ques- tion of who should succeed the Prophet and lead the new Islamic state that created the divide. One group of Muslims (the larger group) elected Abu Bakr, a close companion of the Prophet as the next caliph (leader) of the Muslims and he was then appointed. However, a smaller group believed that the Prophet's son-in-law, Ali, should become the caliph. Muslims who believe that Abu Bakr should be the next leader have come to be known as Sunni. Muslims who believe Ali should have been the next leader are now known as Shia. The use of the word successor should not be confused to mean that that those that followed the Prophet Muhammad were also prophets - both Shia and Sunni agree that Muhammad was the final prophet. How do Sunni and Shia differ on beliefs? Initially, the difference between Sunni and Shia was merely a difference concerning who should lead the Muslim community. -

India-Bangladesh Border Haats BRIEFING PAPER #1/2020 Unnayan Shamannay

India-Bangladesh Border Haats BRIEFING PAPER #1/2020 Unnayan Shamannay Role of Border Haat in Management of India-Bangladesh Border Joyeeta Bhattacharjee* The border haats have been transformational in the management of India and Bangladesh border. Traditionally, border management was perceived, from the prism of security, therefore, restrictions were imposed on the people in the bordering areas, thus hampering development. Given the security-centric approach to the border, India undertook a policy of restraining development in the areas adjacent to the international boundary. Unfortunately, such a policy backfired and instead of securing the border, increased vulnerabilities and the border region became a hub of illegal activities. The haats were established to bolster development in the border region by generating livelihood opportunities and controlling cross-border illegal activities. This Briefing Paper studies the role and impact of the border haats in the management of the India- Bangladesh border. Understanding Border The border management policies are determined by Management the nature of bilateral relationship a country enjoys with the other country across the border. Despite Border management has two major objectives – divergent approaches, security is a key component of firstly, to facilitate the movement of legitimate goods border management across the globe. For example, and people across the border between two India shares around 15,000 kilometres of land sovereign countries; and secondly, to ensure the borders with six countries, however, its policies are security of the country by restricting entry of illegal not uniform. The country follows different policies goods and those individuals across the border who based on the nature of the relationship with a specific 1 might disturb the peace. -

Bangladesh: Back to the Future

BANGLADESH: BACK TO THE FUTURE Asia Report N°226 – 13 June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE LEGACY OF THE CARETAKER GOVERNMENT ......................................... 2 III. SHATTERED HOPES UNDER THE AWAMI LEAGUE .......................................... 4 A. THE FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT ...................................................................................................... 4 B. CRACKDOWN ON THE OPPOSITION ............................................................................................... 5 C. POLITICISATION OF THE SECURITY FORCES AND JUDICIARY ........................................................ 6 D. WAR CRIMES TRIALS ................................................................................................................... 7 E. CORRUPTION ................................................................................................................................ 8 F. THE AWAMI LEAGUE IN POWER ................................................................................................... 8 IV. THE OTHER PARTIES ................................................................................................... 9 A. THE BNP .................................................................................................................................... -

MYANMAR Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung

I Complex MYANMAR Æ Emergency Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State Imagery analysis: Multiple Dates | Published 18 October 2018 | Version 1.0 CE20130326MMR 92°11'0"E 92°18'0"E 92°25'0"E 92°32'0"E 92°39'0"E 92°46'0"E Thimphu NUMBER OF AFFECTED SETTLEMENTS GROUPED BY LEVEL OF DESTRUCTION ¥¦¬ Level of destruction Buthidaung Maungdaw Rathedaung Total C H I N A Less than 50% destroyed 71 59 4 134 I N D I A More than 50% destroyed 18 62 80 N N Dhaka " Completely destroyed (>90%) 7 156 15 178 " 0 ' 0 ' ¥¦¬ 5 5 2 2 ° ° 1 1 2 Hano¥¦¬i In Tu Lar 2 M YA N M A R ¥¦¬Naypyidaw Vientiane Map location ¥¦¬ T H A I L A N D N N " " 0 ' 0 ' 8 Shee Dar 8 Bangkok 1 1 ° ° 1 1 ¥¦¬ 2 2 Phnom Penh ¥¦¬ Ah Shey Kha Maung Seik Nan Yar Kaing (NaTaLa) Nga/Myin Baw Ku Lar N N " " 0 ' 0 Hpon Thi Laung Boke ' 1 1 Affected settlements in 1 1 ° ° 1 1 2 Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Mu Hti Pa Da Kar Taung 2 Rathedaung Townships of Pa Da Kar Ywar Thit Min Gyi (Ku Lar) Wet Kyein Rakhine State in Myanmar Pe Lun Kha Mway Saung Paing Nyar This map illustrates areas of satellite-detected destroyed or otherwise damaged settlements Goke Pi N N " " 0 ' 0 ' in Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung 4 See inset for close-up view 4 ° ° 1 1 2 Townships in Northern Rakhine State in of destroyed structures 2 Myanmar. -

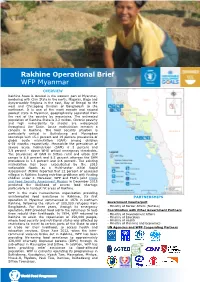

Rakhine Operational Brief WFP Myanmar

Rakhine Operational Brief WFP Myanmar OVERVIEW Rakhine State is located in the western part of Myanmar, bordering with Chin State in the north, Magway, Bago and Ayeyarwaddy Regions in the east, Bay of Bengal to the west and Chittagong Division of Bangladesh to the northwest. It is one of the most remote and second poorest state in Myanmar, geographically separated from the rest of the country by mountains. The estimated population of Rakhine State is 3.2 million. Chronic poverty and high vulnerability to shocks are widespread throughout the State. Acute malnutrition remains a concern in Rakhine. The food security situation is particularly critical in Buthidaung and Maungdaw townships with 15.1 percent and 19 percent prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM) among children 6-59 months respectively. Meanwhile the prevalence of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is 2 percent and 3.9 percent - above WHO critical emergency thresholds. The prevalence of GAM in Sittwe rural and urban IDP camps is 8.6 percent and 8.5 percent whereas the SAM prevalence is 1.3 percent and 0.6 percent. The existing malnutrition has been exacerbated by the 2015 nationwide floods as a Multi-sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA) reported that 22 percent of assessed villages in Rakhine having nutrition problems with feeding children under 2. Moreover, WFP and FAO’s joint Crops and Food Security Assessment Mission in December 2015 predicted the likelihood of severe food shortage particularly in hardest hit areas of Rakhine. WFP is the main humanitarian organization providing uninterrupted food assistance in Rakhine. Its first PARTNERSHIPS operation in Myanmar commenced in 1978 in northern Rakhine, following the return of 200,000 refugees from Government Counterpart Bangladesh. -

Siti Umayatun, S.Hum. TESIS

PERAN KOREA MUSLIM FEDERATION (KMF) DALAM PERTUMBUHAN ISLAM DI KOREA SELATAN TAHUN 1967-2015 M Disusun Oleh : Siti Umayatun, S.Hum. NIM : 1520510121 TESIS Diajukan Kepada Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Kalijaga Untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Guna Memperoleh Gelar Master of Arts (M. A) Program Studi Interdisciplinary Islamic Studies (IIS) Konsentrasi Sejarah KebudayaanIslam YOGYAKARTA 2017 ABSTRAK Pada era Modern, bersamaan dengan Perang Korea tahun 1950-1953 M benih ajaran agama Islam mulai tumbuh di semenanjung Korea Selatan melalui kontak hubungan dengan pasukan perdamaian Turki. Dakwah bil hal tentara Turki selama terjadi perang melahirkan beberapa Muallaf generasi pertama Muslim Korea. Jumlah mereka pertahunnya meningkat sehingga terbentuk perkumpulan Muslim Korea dan tahun 1967 M menjadi organisasi Korea Muslim Federation (KMF) yang statusnya diakui oleh pemerintah Korea bahkan diberi surat izin mendirikan bangunan. Semua Muslim yang diorganisir KMF awalnya benar-benar bagian integral dari bangsa Korea yang menjadi Muallaf bukan karena kedatangan imigran Muslim dari negara-negara Islam. Sejak tahun 1970-an pemerintah Korea membantu KMF dalam perkembangan Islam, padahal selama itu mereka simpati pada Zionis dan pro Israel bahkan sejak masa kemerdekaan sampai sekarang berada di bawah naungan Amerika. Pemerintah Korea memperlakukan Muslim atas dasar sama dengan kelompok agama lainnya, tidak mendiskriminasi bahkan membuka pintu lebar-lebar dakwah KMF dengan memberikan sebidang tanah untuk pembangunan masjid dan universitas Islam. Meski Islam agama baru dan minoritas di Korea namun memiliki posisi terhormat dan stategis. Dalam memobilisasi perkembangan Islam, KMF melakukan kaderisasi mengirim beberapa pemuda Muslim Korea ke negara- negara Muslim untuk belajar Islam dan melakukan riset. Terlihat bahwa minoritas Muslim Korea punya nasip lebih cerah dan menjanjikan jika dibandingkan dengan keadaan minoritas Muslim lainnya. -

Of the Rome Statute

ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 1/146 RH PT Cour Penale (/\Tl\) _ni _t_e__r an _t_oi _n_a_l_e �i��------------------ ----- International �� �d? Crimi nal Court Original: English No.: ICC-01/19 Date: 4 July 2019 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Olga Herrera Carbuccia, Presiding Judge Judge Robert Fremr Judge Geoffrey Henderson SITUATION IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH / REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR PUBLIC With Confidential EX PARTE Annexes 1, 5, 7 and 8, and Public Annexes 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 and 10 Request for authorisation of an investigation pursuant to article 15 Source: Office of the Prosecutor ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 2/146 RH PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Ms Fatou Bensouda Mr James Stewart Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Counsel Support Section Mr Peter Lewis Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section Mr Philipp Ambach No. ICC-01/19 2/146 4 July 2019 ICC-01/19-7 04-07-2019 3/146 RH PT CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 5 II. LEVEL OF CONFIDENTIALITY AND REQUESTED PROCEDURE .................... 8 III. PROCEDURAL -

TITLE of UNIT What Do Muslims Do at the Mosque

Sandwell SACRE RE Support Materials 2018 Unit 1.8 Beginning to learn about Islam. Muslims and Mosques in Sandwell Year 1 or 2 Sandwell SACRE Support for RE Beginning to learn from Islam : Mosques in Sandwell 1 Sandwell SACRE RE Support Materials 2018 Beginning to Learn about Islam: What can we find out? YEAR GROUP 1 or 2 ABOUT THIS UNIT: Islam is a major religion in Sandwell, the UK and globally. It is a requirement of the Sandwell RE syllabus that pupils learn about Islam throughout their primary school years, as well as about Christianity and other religions. This unit might form part of a wider curriculum theme on the local environment, or special places, or ‘where we live together’. It is very valuable for children to experience a school trip to a mosque, or another sacred building. But there is also much value in the virtual and pictorial encounter with a mosque that teachers can provide. This unit looks simply at Mosques and worship in Muslim life and in celebrations and festivals. Local connections are important too. Estimated time for this unit: 6 short sessions and 1 longer session if a visit to a mosque takes place. Where this unit fits in: Through this unit of work many children who are not Muslims will do some of their first learning about the Islamic faith. They should learn that it is a local religion in Sandwell and matters to people they live near to. Other children who are Muslims may find learning from their own religion is affirming of their identity, and opens up channels between home and school that hep them to learn. -

September 2020 1

SEPTEMBER 2020 1 SEPTEMBER 2020 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS MONTH IN REVIEW 4 CHRONOLOGY 7 ● POLITICAL PRISONERS 7 ○ ARRESTS 7 ○ CHARGES 8 ○ SENTENCES 12 ○ RELEASES 13 ○ ARRESTS BY EAO 14 ○ RELEASES BY EAO 14 ○ DISAPPEARANCES 14 ● RESTRICTIONS ON CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS 14 ● REFERENCES 22 SEPTEMBER 2020 3 MONTH IN REVIEW Freedom of Speech and Expression September 15 was the UN International Democracy Day. Democracy is “a form of government in which the people have the authority to choose their governing legislation.” However, the values and standards of democracy have not yet been established in Burma and the people’s authority over their daily lives and fundamental rights is fading. It is clearly shown that Burma is deviating from the path of democracy as those who exercise their right to freedom of speech and expression which is a fundamental right in democratization, face not only oppression and restrictions but arbitrary detentions and arrests. This September, freedom of speech and expression became more severely restricted. A total of 34 students and members of student unions from Rangoon, Mandalay, Meiktila Monywa, Pakokku and Pyay Townships were charged under Section 19 of PAPPL or Section 505(a)(b) of the Penal Code or Section 25 of the Natural Disaster Management Law for staging protests in related to the conflict in Arakan. Among them, 23 students were formally arrested and one was sentenced. In addition to this, four civilians were arrested. Moreover, Sithu Aung a.k.a Saung Kha was fined under Section 19 of PAPPL for protesting to reinstate internet services in Arakan and Chin states.