Affirmation of Shan Identities Through Reincarnation and Lineage of the Classical Shan Romantic Legend 'Khun Sam Law'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS

Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Table of Contents Foreword 3 About this report 5 Highlights in Achievements 7 Progress and Achievements 9 ....... Access to services to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV improved 9 ....... Access to services to prevent transmission of HIV in injecting drug use ....... improved 18 ....... Knowledge and attitudes improved 27 ....... Access to services for HIV care and support improved 30 Fund Management 41 ....... Programmatic and Financial Monitoring 41 ....... Financial Status and Utilisation of Funds 43 Operating Environment 44 Annexe 1: Implementing Partners expenditure and budgets 45 Annexe 2: Summary of Technical Progress Apr 2004–Mar 2007 49 Annexe 3: Achievements by Implementing Partners Round II, II(b) 50 Annexe 4: Guiding principles for the provision of humanitarian assistance 57 Acronyms and abbreviations 58 1 Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS 2 Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Foreword This report will be the last for the Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar (FHAM), covering its fourth and final year of operation (the fiscal year from April 2006 through March 2007). Created as a pooled funding mechanism in 2003 to support the United Nations Joint Programme on AIDS in Myanmar, the FHAM has demonstrated that international resources can be used to finance HIV services for people in need in an accountable and transparent manner. As this report details, progress has been made in nearly every area of HIV prevention – especially among the most at-risk groups related to sex work and drug use – and in terms of care and support, including anti-retroviral treatment. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

“White Elephant” the King's Auspicious Animal

แนวทางการบริหารการจัดการเรียนรู้ภาษาจีนส าหรับโรงเรียนสองภาษา (ไทย-จีน) สังกัดกรุงเทพมหานคร ประกอบด้วยองค์ประกอบหลักที่ส าคัญ 4 องค์ประกอบ ได้แก่ 1) เป้าหมายและ หลักการ 2) หลักสูตรและสื่อการสอน 3) เทคนิคและวิธีการสอน และ 4) การพัฒนาผู้สอนและผู้เรียน ค าส าคัญ: แนวทาง, การบริหารการจัดการเรียนรู้ภาษาจีน, โรงเรียนสองภาษา (ไทย-จีน) Abstract This study aimed to develop a guidelines on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration. The study was divided into 2 phases. Phase 1 was to investigate the present state and needs on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration from the perspectives of the involved personnel in Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration Phase 2 was to create guidelines on managing Chinese language learning for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) under the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration and to verify the accuracy and suitability of the guidelines by interviewing experts on teaching Chinese language and school management. A questionnaire, a semi-structured interview form, and an evaluation form were used as tools for collecting data. Percentage, mean, and Standard Deviation were employed for analyzing quantitative data. Modified Priority Needs Index (PNImodified) and content analysis were used for needs assessment and analyzing qualitative data, respectively. The results of this research found that the actual state of the Chinese language learning management for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) in all aspects was at a high level ( x =4.00) and the expected state of the Chinese language learning management for Bilingual Schools (Thai – Chinese) in the overall was at the highest level ( x =4.62). The difference between the actual state and the expected state were significant different at .01 level. -

Final Report

Prevention of Human Trafficking in Children, Youth and Women FINAL REPORT 06 June 2017 – 06 June 2018 Promoting the Rule of Law Project Grant Number:PRL-G-008-002 Implemented by: Mawk Kon Local Development Organization Nang Voe Phart Ph. 08423943, 095250848 Khattar Street, MyoThit Ward (3), Keng Tung Tsp, Eastern Shan State, Myanmar. Accomplishments In Milestone A, we had fully executed grant agreement, prepared detailed monthly work plan for all activities, two staffs had attended of key organization staff Project-sponsored USAID Rules & Regulations Training at Yangon. And We were prepared draft suitable core group identified/ forming workshop including agendas, invitees list, handouts and other deliverable materials and also we were prepared IEC draft design such as Pamphlet, Vinyl, Planners and Cap. We had created organizational bank account for these Prevention of Human Trafficking in Children and we also met the target with grant agreement. In Milestone B, We had identified and formed core group workshops at Keng Tung and Tachileik Township. We can be formed (11) core group in Keng Tung and (6) core group in Tachileik, cumulative total (2) times. Totally participants are male (33) & female (21) and involved in each core group workshop. Therefore some core group were actively participated, can be made for networks in these workshop, it directly depend on migration & trafficking events at Thailand and some country and then its encourage to participate for next awareness, campaign & TOT training relevant with migration and human trafficking. In these two workshops, we were only distributing/ supporting handouts but we didn’t used any other deliverable materials. -

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY of OPIUM REDUCTION in BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES from the WA REGION Mr. Sai Lone a Thesis Submitted in Part

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF OPIUM REDUCTION IN BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WA REGION Mr. Sai Lone A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Program in International Development Studies Faculty of Political Science Chulalongkorn University Academic Year 2008 Copyright of Chulalongkorn University เศรษฐศาสตรการเมืองของการปราบฝนในประเทศพมา: มุมมองระดับทองถิ่นในเขตวา นายไซ โลน วิทยานิพนธน ี้เปนสวนหนึ่งของการศึกษาตามหลกสั ูตรปริญญาศิลปศาสตรมหาบัณฑิต สาขาวิชาการพัฒนาระหวางประเทศ คณะรัฐศาสตร จุฬาลงกรณมหาวิทยาลัย ปการศึกษา 2551 ลิขสิทธิ์ของจุฬาลงกรณมหาวิทยาลัย Thesis title: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF OPIUM REDUCTION IN BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WA REGION By: Mr. Sai Lone Field of Study: International Development Studies Thesis Principal advisor: Niti Pawakapan, Ph. D. Accepted by the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master’s Degree ___________________________ Dean of the Faculty of Political Science (Professor Charas Suwanmala, Ph.D.) THESIS COMMITTEE ___________________________ Chairperson (Professor Supang Chantavanich, Ph.D.) ___________________________ Thesis Principal Advisor (Niti Pawakapan, Ph.D.) ___________________________ External Examiner (Decha Tangseefa, Ph.D.) นายไซ โลน: เศรษฐศาสตรการเมืองของการปราบฝนในประเทศพมา: มุมมองระดับ ทองถิ่นในเขตวา (THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF OPIUM REDUCTION IN BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WA REGION) อ. ทปรี่ ึกษา: ดร.นิติ ภวัครพันธุ. 133 หนา. งานวิจัยชิ้นนี้เนนศึกษาผลกระทบดานเศรษฐกิจสังคมของโครงการพัฒนาชนบทที่ดําเนินงานโดยองคกร -

Th E Phaungtaw-U Festival

NOTES TH_E PHAUNGTAW-U FESTIVAL by SAO SAIMONG* Of the numerous Buddhist festivals in Burma, the Phaungtaw-u Pwe (or 'Phaungtaw-u Festival') is among the most famous. I would like to say a few words on its origins and how the Buddhist religion, or 'Buddha Sii.sanii.', came to Burma, particularly this part of Burma, the Shan States. To Burma and Thailand the term 'Buddha Sii.sanii.' can only mean the Theravii.da Sii.sanii. or simply the 'Sii.sanii.'. I Since Independence this part of Burma has been called 'Shan State'. During the time of the Burmese monarchy it was known as Shanpyi ('Shan Country', pronounced 'Shanpye'). When th~ British came the whole unit was called Shan States because Shanpyi was made up of states of various sizes, from more than 10,000 square miles to a dozen square miles. As I am dealing mostly with the past in this short talk I shall be using this term Shan States. History books of Burma written in English and accessible to the outside world tell us that the Sii.sanii. in its purest form was brought to Pagan as the result of the conversion by the Mahii.thera Arahan of King Aniruddha ('Anawrahtii.' in Burmese) who then proceeded to conquer Thaton (Suddhammapura) in AD 1057 and brought in more monks and the Tipitaka, enabling the Sii.sanii. to be spread to the rest of the country. We are not told how Thaton itself obtained the Sii.sanii.. The Mahavamsa and chronicles in Burma and Thailand, however, tell us that the Sii.sanii. -

Chapter 1 Introduction to the Geology of Myanmar

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 2, 2021 Chapter 1 Introduction to the geology of Myanmar KHIN ZAW1*, WIN SWE2, A. J. BARBER3, M. J. CROW4 & YIN YIN NWE5 1CODES ARC Centre of Excellence in Ore Deposits, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 126, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia 2Myanmar Geosciences Society, 303 MES Building, Hlaing University Campus, Yangon, Myanmar 3Department of Earth Sciences, Southeast Asian Research Group, Royal Holloway, Egham TW20 0EX, UK 428a Lenton Road, The Park, Nottingham NG7 1DT, UK 5Myanmar Applied Earth Sciences Association (MAESA), 15 (C) Pyidaungsu Lane, Bahan, Yangon, Myanmar *Correspondence: [email protected] Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar (Pyidaungsu Tham- northern part of the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Mottama mada Myanmar NaingNganDaw), formerly Burma, occupies (Martaban). The central lowlands are divided into two unequal the northwestern part of the Southeast Asian peninsula. It is parts by the Bago Yoma Ranges, the larger Ayeyarwaddy Valley bounded to the west by India, Bangladesh, the Bay of Bengal and the smaller Sittaung Valley. The Bago Yoma Ranges pass and the Andaman Sea, and to the east by China, Laos and Thai- northwards into a line of extinct volcanoes with small crater land. It comprises seven administrative regions (Ayeyarwaddy lakes and eroded cones; the largest of these is Mount Popa (Irrawaddy), Bago, Magway, Mandalay, Sagaing, Tanintharyi (1518 m). Coastal lowlands and offshore islands margin the (Tenasserim) and Yangon) and seven states (Chin, Kachin, Bay of Bengal to the west of the Rakhine Yoma and the Anda- Kayah, Kayin, Mon, Rakhine (Arakan) and Shan). -

Federal Register/Vol. 81, No. 210/Monday, October 31, 2016/Notices TREASURY—NBES FEE SCHEDULE—EFFECTIVE JANUARY 3, 2017

75488 Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 210 / Monday, October 31, 2016 / Notices Federal Reserve System also charges a reflective of costs associated with the The fees described in this notice funds movement fee for each of these processing of securities transfers. The apply only to the transfer of Treasury transactions for the funds settlement off-line surcharge, which is in addition book-entry securities held on NBES. component of a Treasury securities to the basic fee and the funds movement Information concerning fees for book- transfer.1 The surcharge for an off-line fee, reflects the additional processing entry transfers of Government Agency Treasury book-entry securities transfer costs associated with the manual securities, which are priced by the will increase from $50.00 to $70.00. Off- processing of off-line securities Federal Reserve, is set out in a separate line refers to the sending and receiving transfers. Federal Register notice published by of transfer messages to or from a Federal Treasury does not charge a fee for the Federal Reserve. Reserve Bank by means other than on- account maintenance, the stripping and line access, such as by written, reconstitution of Treasury securities, the The following is the Treasury fee facsimile, or telephone voice wires associated with original issues, or schedule that will take effect on January instruction. The basic transfer fee interest and redemption payments. 3, 2017, for book-entry transfers on assessed to both sends and receives is Treasury currently absorbs these costs. NBES: TREASURY—NBES FEE SCHEDULE—EFFECTIVE JANUARY 3, 2017 [In dollars] Off-line Transfer type Basic fee surcharge On-line transfer originated ...................................................................................................................................... -

Analysis of Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Shan State and Strategic Options to Address Them

Final Report Analysis of Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Shan State and Strategic Options to Address them FOREST MONREC M i n n is o t ti ry va of ser Natu l Con ral Re enta sourc ironm es nv & E 2 Final Report Analysis of Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Shan State and Strategic Options to Address them Authors Aung Aung Myint, National Consultant on analysis of drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in Shan State, ICIMOD-GIZ REDD+ project [email protected]: +95 9420705116. December 2018 i Copyright © 2018 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial, No Derivatives 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) GP Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Production team Bill Wolfe (Consultant editor) Rachana Chettri (Editor) Dharma R Maharjan (Graphic designer) Asha Kaji Thaku (Editorial assistance) Cover photo: On the way from MongPyin to KyaingTong, eastern Shan State. Most of the photos used in the report were taken by the consultant on the eld survey of the Illicit Crop Monitoring in Myanmar-Opium Survey (ICMP) project (TD/MYA/G43 & TD/MYA/G44) under UNODC in 2014 and 2015. Reproduction This publication may be produced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-prot purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. ICIMOD would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. -

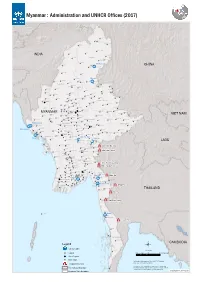

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017)

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017) Nawngmun Puta-O Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Sumprabum Lahe Tanai INDIA Tsawlaw Hkamti Kachin Chipwi Injangyang Hpakan Myitkyina Lay Shi Myitkyina CHINA Mogaung Waingmaw Homalin Mohnyin Banmauk Bhamo Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Momauk Pinlebu Katha Sagaing Mansi Muse Wuntho Konkyan Kawlin Tigyaing Namhkan Tonzang Mawlaik Laukkaing Mabein Kutkai Hopang Tedim Kyunhla Hseni Manton Kunlong Kale Kalewa Kanbalu Mongmit Namtu Taze Mogoke Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Falam Mingin Thabeikkyin Ye-U Khin-U Shan (North) ThantlangHakha Tabayin Hsipaw Namphan ShweboSingu Kyaukme Tangyan Kani Budalin Mongyai Wetlet Nawnghkio Ayadaw Gangaw Madaya Pangsang Chin Yinmabin Monywa Pyinoolwin Salingyi Matman Pale MyinmuNgazunSagaing Kyethi Monghsu Chaung-U Mongyang MYANMAR Myaung Tada-U Mongkhet Tilin Yesagyo Matupi Myaing Sintgaing Kyaukse Mongkaung VIET NAM Mongla Pauk MyingyanNatogyi Myittha Mindat Pakokku Mongping Paletwa Taungtha Shan (South) Laihka Kunhing Kengtung Kanpetlet Nyaung-U Saw Ywangan Lawksawk Mongyawng MahlaingWundwin Buthidaung Mandalay Seikphyu Pindaya Loilen Shan (East) Buthidaung Kyauktaw Chauk Kyaukpadaung MeiktilaThazi Taunggyi Hopong Nansang Monghpyak Maungdaw Kalaw Nyaungshwe Mrauk-U Salin Pyawbwe Maungdaw Mongnai Monghsat Sidoktaya Yamethin Tachileik Minbya Pwintbyu Magway Langkho Mongpan Mongton Natmauk Mawkmai Sittwe Magway Myothit Tatkon Pinlaung Hsihseng Ngape Minbu Taungdwingyi Rakhine Minhla Nay Pyi Taw Sittwe Ann Loikaw Sinbaungwe Pyinma!^na Nay Pyi Taw City Loikaw LAOS Lewe -

Report Administration of Burma

REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA FOR THE YEAR 1933=34 RANGOON SUPDT., GOVT. PRINTING AND STATIONERY, BURMA 1935 LIST OF AGENTS FOR THE SALE~OF GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN BURMA. AllERICAN BAPTIST llIISSION PRESS, Rangoon. BISWAS & Co., 226 Lewis Street, Rangoon. BRITISH BURMA PRESS BRANCH, Rangoon .. ·BURMA BOO!, CLUB, LTD., Poat Box No. 1068, Rangoon. - NEW LIGHT 01' BURlL\ Pl?ESS, 61 Sule Pagoda Road, Rangoon. PROPRIETOR, THU DHA!IIA \VADI PRE,S, 16-80 lliaun!l :m,ine Street. Rangoon. RANGOOX TIMES PRESS, Rangoon. THE CITY BOOK CLUB, 98 Phayre Street, Rangoon . l\IESSRS, K. BIN HOON & Soi.:s, Nyaunglebin. MAUNG Lu GALE, Law Book Depot, 42 Ayo-o-gale. Manrlalay. ·CONTINENTAL TR.-\DDiG co.. No. 353 Lower Main Road. ~Ioulmein. lN INDIA. BOOK Co., Ltd., 4/4A College Sq<1are, Calcutta. BUTTERWORTH & Co. Undlal, "Ltd., Calcutta . .s. K. LAHIRI & Co., 56 College Street, Calcutta. ,v. NEWMAN & Co., Calcutta. THACKER, SPI:-K & Co., Calcutta, and Simla. D. B. TARAPOREVALA, Soxs & Co., Bombay. THACKER & Co., LTD., Bombay. CITY BOO!! Co., Post Box No. 283, l\Iadras. H!GGINBOTH.UI:& Co., Madras. ·111R. RA~I NARAIN LAL, Proprietor, National1Press, Katra.:Allahabad. "MESSRS. SAllPSON WILL!A!II & Co., Cawnpore, United Provinces, IN }j:URUPE .-I.ND AMERICA, -·xhc publications are obtainable either ~direct from THE HIGH COMMISS!Oli:ER FOR INDIA, Public Department, India House Aldwych, London, \V.C. 2, or through any bookseller. TABLE OF CONTENTS. :REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA FOR THE YEAR 1933-34. Part 1.-General Summary. Part 11.-Departmental Chapters. CHAPTER !.-PHYSICAL AND POLITICAT. GEOGRAPHY. "PHYSICAL-- POLITICAL-co11clcl. -

Geology & Mineral Resources of Myanmar

Geology & Mineral Resources of Myanmar KYAW KYAW OHN Assistant Director (Geologist) DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY AND MINERAL EXPLORATION MINISTRY OF MINES 1 Introduction Organization Morpho-Tectonic Geology Mineral Occurrence Investment Cooperation Conclusion Belts of Setting of & Mining Activities Opportunities with Myanmar Myanmar in Myanmar International Myanmar is endowed with resources of arable land, natural gas, mineral deposits, fisheries, forestry and manpower. 2 Introduction Organization Morpho-Tectonic Geology Mineral Occurrence Investment Cooperation Conclusion Belts of Setting of & Mining Activities Opportunities with Myanmar Myanmar in Myanmar International Area : 678528 sq.km Coast Line : 2100 km Border : 4000 km NS Extend : 2200 km EW Extend : 950 km Population : >51millions(est:) Region : 7 State: : 7 Location : 10º N to 28º 30' 92º 30' E to 101º30' 3 Introduction Organization Morpho-Tectonic Geology Mineral Occurrence Investment Cooperation Conclusion Belts of Setting of & Mining Activities Opportunities with Myanmar Myanmar in Myanmar International Union Minister Deputy Minister No.(1) No.(2) Myanmar Myanmar Department of Geological Department Mining Mining Gems Pearl Survey &Mineral of Enterprise Enterprise Enterprise Enterprise Exploration Mines Lead Coal Gold Gems, Pearl Geological Mineral Zinc Lime stone Tin Jade Breeding Survey Policy Silver Industrial Tungsten & Cultivating Mineral formulation, Copper Minerals Rare Earth Jewelry Exploration Regulation Iron Manganese Titanium Laboratory measures Nickel Decorative